John Carter (film)

| John Carter | |

|---|---|

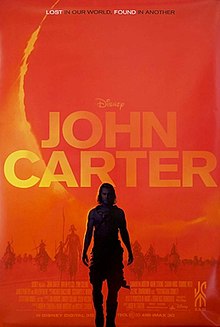

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Andrew Stanton |

| Screenplay by |

|

| Based on | A Princess of Mars by Edgar Rice Burroughs |

| Produced by |

|

| Starring | |

| Cinematography | Dan Mindel |

| Edited by | Eric Zumbrunnen |

| Music by | Michael Giacchino |

Production company | |

| Distributed by | Walt Disney Studios Motion Pictures[2] |

Release dates |

|

Running time | 132 minutes[3] |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget |

|

| Box office | $284.1 million |

John Carter is a 2012 American science fiction action-adventure film directed by Andrew Stanton, written by Stanton, Mark Andrews, and Michael Chabon, and based on A Princess of Mars, the first book in the Barsoom series of novels by Edgar Rice Burroughs. Produced by Jim Morris, Colin Wilson and Lindsey Collins, it stars Taylor Kitsch in the title role, Lynn Collins, Samantha Morton, Mark Strong, Ciarán Hinds, Dominic West, James Purefoy and Willem Dafoe. It chronicles the first interplanetary adventure of John Carter and his attempts to mediate civil unrest amongst the warring kingdoms of Barsoom.

Several attempts to adapt the Barsoom series had been made since the 1930s by various major studios and producers. Most of these efforts ultimately stalled in development hell. In the late-2000s, Walt Disney Pictures began a concerted effort to adapt Burroughs' works to film, after an abandoned venture in the 1980s. The project was driven by Stanton, who had pressed Disney to renew the screen rights from the Burroughs estate. Stanton became the new film's director in 2009. It was his live-action debut, after his directorial work for Disney on the Pixar animated films Finding Nemo and WALL-E.[4][5] Filming began in November 2009, with principal photography underway in January 2010, wrapping seven months later in July.[6][7] Michael Giacchino, who scored many Pixar films, composed the music.[8] Like Pixar's Brave that same year, the film is dedicated to the memory of Steve Jobs.[9]

It was released in the United States by Walt Disney Studios Motion Pictures on March 9, 2012, marking the centennial of the titular character's first appearance. It was presented in Disney Digital 3D, RealD 3D and IMAX 3D formats.[10][11][12] John Carter received mixed reviews, with praise for its visuals, Giacchino's score, and the action sequences, but criticism of the characterization and plot. It failed at the North American box office, but set an opening-day record in Russia.[13] It grossed $284 million at the worldwide box office, resulting in a $200 million writedown for Disney, becoming one of the biggest box office bombs in history and also becoming the film with the largest estimated box-office loss adjusted for inflation ever, losing $149–265 million. With a total cost of $350 million, including an estimated production budget of $263 million, it is one of the most expensive films ever made. Due to its box office performance, Disney cancelled plans for Gods of Mars and Warlord of Mars, the rest of the trilogy Stanton had planned.[14][15] Much of the film's failure has been attributed to its promotion, which has been called "one of the worst marketing campaigns in movie history".[16][17][18]

Plot

[edit]In 1881, Edgar Rice Burroughs attends the funeral of his uncle, John Carter, a former American Civil War Confederate Army captain who died suddenly. Per Carter's instructions, the body is put in a tomb that can be unlocked only from the inside. His attorney gives Carter's personal journal to Burroughs to read.

In a flashback to 1868 in the Arizona Territory, Union Colonel Powell arrests Carter with hopes that Carter will help in fighting local Apache. Carter escapes his holding cell, but fails to get far with U.S. cavalry soldiers in close pursuit. After a run-in with a band of Apaches, Carter and a wounded Powell are chased until they hide in a cave that turns out to be filled with gold. A Thern appears in the cave at that moment and, surprised by the two men, attacks them with a knife; Carter kills him but accidentally activates the Thern's powerful medallion and is unwittingly transported to a ruined and dying planet, Barsoom, known to Carter as Mars. Because of his different bone density and the planet's low gravity, Carter is able to jump high and perform feats of incredible strength. He is captured by the Tharks, a nomadic tribe of Green Martians and their Jeddak, Tars Tarkas.

Elsewhere on Barsoom, the Red Martian cities of Helium and Zodanga have been at war for a thousand years. Sab Than, Jeddak of Zodanga, armed with a special weapon obtained from the Thern leader Matai Shang, proposes a cease-fire and an end to the war by marrying the Princess of Helium, Dejah Thoris. The Princess escapes and is rescued by Carter.

Carter, Dejah, and Tarkas's daughter, Sola, reach a spot in a sacred river to find a way for Carter to get back to Earth. They discover that the medallions are powered by a "ninth ray" that is also the source of Sab Than's weapon. They are then attacked by a vicious race called the Warhoon under the direction of Shang. Carter and Dejah are taken back to Zodanga. A demoralized Dejah grudgingly agrees to marry Sab Than and gives Carter instructions on how to use the medallion to return to Earth. Carter decides to stay and is captured by Shang, who explains to him the purpose of Therns and how they manipulate the civilizations of different worlds to their doom, feeding off the planet's resources in the process, and intend to do the same thing with Barsoom by choosing Sab Than to rule the planet. Carter goes back to the Tharks with Sola to request their help. There they discover a ruthless brute, Tal Hajus, has overthrown Tarkas. Carter and an injured Tarkas battle with two enormous Great White-Apes in an arena before Carter kills Hajus, thereby becoming the leader of the Tharks.

The Thark army storms Zodanga, realizing their army is waiting outside Helium, John and the Tharks commandeer the Zodangan airships and fly to Helium. Carter defeats the Zodangan army, while Sab Than is killed and Shang is forced to escape. Carter becomes prince of Helium by marrying Dejah. On their first night, Carter decides to stay forever on Mars and throws away his medallion. Seizing this opportunity, Shang briefly reappears and gives Carter another challenge, sending him back to Earth. Carter embarks on a long quest to find one of their medallions on Earth; after several years he appears to die suddenly and asks for unusual funeral arrangements — consistent with his having found a medallion, since his return to Mars would leave his Earth body in a coma-like state, and makes Burroughs his protector.

Back in the present, Burroughs runs back to Carter's tomb and uses clues to open it. Just as he does so, a Thern appears and raises a weapon before Carter appears and shoots the Thern in the back. He reveals that he had never found another medallion; instead, he devised a scheme to lure a Thern from hiding, thus winning Shang's challenge. Carter then uses the dead Thern's medallion to return to Barsoom.

Cast

[edit]- Taylor Kitsch as John Carter, a Confederate army captain who is transported to Mars.

- Lynn Collins as Dejah Thoris, the Princess of Helium.

- Samantha Morton as Sola, a Thark that works with John Carter.

- Willem Dafoe as Tars Tarkas, the Jeddak of the Tharks and Sola's father.

- Thomas Haden Church as Tal Hajus, a vicious Thark who dislikes John Carter and Tars Tarkas.

- Mark Strong as Matai Shang, the Hekkador of the Therns.

- Ciarán Hinds as Tardos Mors, the Jeddak of Helium and Dejah Thoris' father.

- Dominic West as Sab Than, the Jeddak of Zodanga.

- James Purefoy as Kantos Kan, the Odwar of the ship Xavarian.

- Bryan Cranston as Colonel Powell, a Union colonel who wants John to help his U.S. cavalry soldiers against the Apache.

- Daryl Sabara as Ned, John Carter's nephew.

- Polly Walker as Sarkoja, a merciless Thark who hates Sola.

- David Schwimmer as a young Thark Warrior, a Thark who informs Tars Tarkas that 18 of the Thark eggs did not hatch.

- Jon Favreau as the Thark bookmaker, a Thark who collects the bets on any conflict.

- Don Stark as Dix, a shopkeeper at an Arizona town where John Carter stops.

- Nicholas Woodeson as Dalton, John Carter's executor who summons Edgar.

- Art Malik as Zodangan General.

Development

[edit]Origins

[edit]

The film is largely based on A Princess of Mars (1912), the first in a series of 11 Burroughs novels to feature the interplanetary hero John Carter (and in later volumes the adventures of his children with Dejah Thoris). The story was originally serialized in six monthly installments (from February through to July 1912) in the pulp magazine The All-Story; those chapters, originally titled "Under the Moons of Mars", were then collected as a novel and published in hardcover five years later from A. C. McClurg.[citation needed]

Bob Clampett involvement

[edit]In 1931, director Bob Clampett approached Edgar Rice Burroughs with the idea of adapting A Princess of Mars into a feature-length animated film. Burroughs responded enthusiastically, recognizing that a regular live-action feature would face various limitations to adapt accurately, so he advised Clampett to write an original animated adventure for John Carter.[19] Working with Burroughs' son John Coleman Burroughs in 1935, Clampett used rotoscope and other hand-drawn techniques to capture the action, tracing the motions of an athlete who performed John Carter's powerful movements in the reduced Martian gravity, and designed the green-skinned, 4-armed Tharks to give them a believable appearance. He then produced footage of them riding their eight-legged Thoats at a gallop, which had all of their eight legs moving in coordinated motion; he also produced footage of a fleet of rocketships emerging from a Martian volcano. Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer was to release the cartoons, and the studio heads were enthusiastic about the series.[20]

The test footage, produced by 1936,[21] received negative reactions from film exhibitors across the U.S., especially in small towns; many gave their opinion that the concept of an Earthman on Mars was just too outlandish an idea for midwestern American audiences to accept. The series was not given the go-ahead, and Clampett was instead encouraged to produce an animated Tarzan series, an offer that he later declined. Clampett recognized the irony in MGM's decision, as the Flash Gordon movie serial, released in the same year by Universal Studios, was highly successful. He speculated that MGM believed that serials were played only to children during Saturday matinees, whereas the John Carter tales were intended to be seen by adults during the evening. The footage that Clampett produced was believed lost for many years, until Burroughs' grandson, Danton Burroughs, in the early 1970s found some of the film tests in the Edgar Rice Burroughs Inc. archives.[20] Had A Princess of Mars been released, it might have preceded Walt Disney's Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs (1937) to become the first American feature-length animated film.[22]

Disney progression

[edit]During the late 1950s, stop-motion animation effects director Ray Harryhausen expressed interest in filming the novels, but it was not until the 1980s that producers Mario Kassar and Andrew G. Vajna bought the rights for the Walt Disney Studios via Cinergi Pictures, with a view to creating a competitor to the original Star Wars trilogy and Conan the Barbarian. Ted Elliott and Terry Rossio were hired to write, while John McTiernan and Tom Cruise were approached to direct and star. The project collapsed because McTiernan realized that visual effects were not yet advanced enough to recreate Burroughs' vision of Barsoom. The project remained at Disney, and Jeffrey Katzenberg was a strong proponent of filming the novels, but the rights eventually returned to the Burroughs estate.[22]

Paramount effort

[edit]Producer James Jacks read Harry Knowles' autobiography, which lavishly praised the John Carter of Mars series. Having read the Burroughs' novels as a child, Jacks was moved to convince Paramount Pictures to acquire the film rights; a bidding war with Columbia Pictures followed. After Paramount and Jacks won the rights, Jacks contacted Knowles to become an adviser on the project and hired Mark Protosevich to write the screenplay. Robert Rodriguez signed on in 2004 to direct the film after his friend Knowles showed him the script. Recognizing that Knowles had been an adviser to many other filmmakers, Rodriguez asked him to be credited as a producer.[22]

Filming was set to begin in 2005, with Rodriguez planning to use the all-digital stages he was using for his production of Sin City, a film based on the graphic novel series by Frank Miller.[22] Rodriguez planned to hire Frank Frazetta, the popular Burroughs and fantasy illustrator, as a designer on the film.[23] Rodriguez had previously stirred-up film industry controversy owing to his decision to credit Sin City's artist/creator Miller as co-director on the film adaptation; as a result, Rodriguez decided to resign from the Directors Guild of America. In 2004, unable to employ a non-DGA filmmaker, Paramount assigned Kerry Conran to direct and Ehren Kruger to rewrite the John Carter script. The Australian Outback was scouted as a shooting location. Conran left the film for unknown reasons and was replaced in October 2005 by Jon Favreau.[22]

Favreau and screenwriter Mark Fergus wanted to make their script faithful to Burroughs' novels, retaining John Carter's links to the American Civil War and ensuring that the Barsoomian Tharks were 15 ft (4.6 m) tall (previous scripts had made them human-sized). Favreau argued that a modern-day soldier would not know how to fence or ride a horse like Carter, who had been a Confederate officer. The first film he envisioned would have adapted the first three novels in the Barsoom series: A Princess of Mars, The Gods of Mars, and The Warlord of Mars. Unlike Rodriguez and Conran, Favreau preferred using practical effects for his film and cited Planet of the Apes (1968) as his inspiration. He intended to use make-up, as well as CGI, to create the Tharks. In August 2006, Paramount chose not to renew the film rights, preferring instead to focus on its Star Trek franchise. Favreau and Fergus moved on to Marvel Studios' Iron Man.[22]

Return to Disney, Stanton involvement

[edit]

Andrew Stanton, director of the Pixar Animation Studios hits Finding Nemo and WALL-E, lobbied Walt Disney Studios to reacquire the rights from Burroughs' estate. "Since I'd read the books as a kid, I wanted to see somebody put it on the screen," he explained.[24]

Stanton then lobbied Disney heavily for the chance to direct the film, pitching it as "Indiana Jones on Mars". The studio was initially skeptical. Stanton had never directed a live-action film before, and wanted to make the film without any major stars whose names could guarantee an audience, at least on opening weekend. The screenplay was seen as confusing and difficult to follow. However, since Stanton had overcome similar preproduction doubts to make WALL-E and Finding Nemo into hits, the studio approved him as director.[25] Stanton noted he was effectively being "loaned" to Walt Disney Pictures because Pixar is an all-ages brand and John Carter, in his words, was "not going to be an all-ages film".[26]

By 2008, the first draft for Part One of a John Carter film trilogy was completed; the first film is based only on the first novel.[27] In April 2009 author Michael Chabon confirmed he had been hired to revise the script.[28][29][30] "I'm really good at structure and collaborating," Stanton explained, "but Michael is just technically, poetically, and intelligence-wise a better writer".[31][32]

Following the completion of WALL-E, Stanton visited the archives of Edgar Rice Burroughs, Inc., in Tarzana, California, as part of his research.[22] Jim Morris, general manager of Pixar, said the film would have a unique look distinct from Frank Frazetta's illustrations, which they both found dated.[33] He also noted that although he had less time for pre-production than for any of his usual animated projects, the task was nevertheless relatively easy since he had read Burroughs' novels as a child and had already visualized many of their scenes.[34] Stanton prepared for directing by losing 20 pounds (9.1 kg), running 15 miles (24 km) a week, and vowed not to go to his trailer or even sit down except when absolutely necessary to avoid looking like "the privileged animation geek who'd cheated his way to the top".[31]

Production

[edit]Casting

[edit]Stanton said later he had no grand design for the cast, other than having the villains be played by British actors. "I knew that the cast was going to grow with creatures and it was going to grow with different types of races if we were to continue. And it was going to get a little more fantastical", he said.[35]

Many actors were considered for the title role. Aware that Carter's backstory as an officer in the Confederate Army might be a problem for modern audiences, Stanton envisioned the character as disillusioned and disgusted with war in general, apart from the side he fought on. "I wanted to not absolve him of that, but also not make him pro the side he was on. The best I could do was neutralize him". Taylor Kitsch quickly became his choice for the part, due to a scene in the Friday Night Lights television series—his character, angry, is left behind by the bus—that captured Stanton's vision for the character, as Kitsch's pose echoed that of Carter on one cover of the books in Stanton's collection.[35]

Lynn Collins, a Juilliard graduate set in her first major movie role as Dejah Thoris early on, tested with many actors, including Josh Duhamel, using a scene (filmed but cut) where she slaps Carter in the face. "Taylor and I have always had incredible chemistry. It was inevitable that we would get a chance to really explore it and work as a team," she said of her co-star in X-Men Origins: Wolverine (2009). She recalls him coming into the dressing room after their test together and, seeing her smoking, told her she would have to quit if she got the part, which she did. At Disney's insistence, she used a British accent.[35]

Tom Cruise expressed interest in playing the role once production had begun; Collins did not read with him. "I think him and Andrew had some conversations, but I don't think he was ever actually in the mix so to speak", she recalled in 2022, noting that all the actors she read with were 20 years younger than him. Stanton said that as there was at that time the possibility of making two sequels, he kept that in mind. "[I]t would take a while to make these three movies", he recalled. "I'm like, How do I feel about how these people might age in the next five to seven years?"[35]

Willem Dafoe and Samantha Morton played their roles as Tharks wearing motion capture suits while walking on stilts. Cameras attached to their outfits focused on their faces and captured their expressions, which were then used to create their characters' faces. "It's a game, it's a new way of performing", he recalled, noting how physically demanding it was.[35] "Always as an actor you're looking for things to jump off from, to find new ways of thinking, new ways of looking, to be turned on in a different way. The stilts were part of that".[36]

Dafoe also had to do dialogue in Thark, developed for the film by Paul Frommer, who had developed the Na'vi language for Avatar. He had worked before with Stanton on Finding Nemo, where he had come to like him. Dafoe found it pleasantly surprising that, given Stanton's background in animation, he refused to rely on the effects. "He really felt like he had to have the movie, so when we started these scenes, there was no 'oh, the CGI will do that' or 'they'll do that in post," he said, which kept the film character-driven.[36]

Filming

[edit]On 'John Carter', Stanton was crafting a complicated, inter-planetary story with live action period elements and more than 2,000 visual-effects shots delivered by four companies. The director said he coaxed Disney to adopt some of Pixar's iterative style ...

—Columnists Dawn C. Chmielewski and Rebecca Keegan, writing in the Los Angeles Times[24]

Principal photography began at Longcross Studios, London, in January 2010 and ended in Kanab, Utah, in July.[7][37] Other locations in Utah included Lake Powell and Grand, Wayne, and Kane counties.[38][39] Cinematographer Dan Mindel believed that the entire movie should have been shot in the Four Corners region of the southwestern U.S., the only place on Earth he felt could convincingly pass for Mars.[a] "A lot of the studio work that we had done was so compromised because of the choice of studio, the size of the stages, the fact that it was all inside when it should have been outside, all that kind of stuff".[35]

Mindel had taken the job in order to learn how to make a movie with many effects shots. He worked with more restraint than he had been used to. Normally he kept the camera rolling even after the director said "Cut!", a lesson he learned from Jackie Chan while making Shanghai Noon. However, for John Carter, Stanton had planned the shots in such great detail before filming began as to leave little room for improvisation.[35]

Stanton went for a different look for the movie's costuming than that which had been planned by Rodriguez and Frazetta when they were attached to the project several years earlier. Stanton felt that Frazetta's look was "very sexist and it's very male, fanboy dominated". While conceding the sex appeal at the heart of the characters, he believed they still had to seem realistic. "I want anything, whether it's a fish or a robot or a toy or a human being, I want them to be seen as dimensional as possible and be seen as somebody with thoughts and opinions and surprise in how they may react to something, and contradictions".[35]

Throughout production there had been arguments from some of Stanton's friends in Pixar's Braintrust that it would be better for the movie to begin with Carter finding himself on Mars than through the narrative device of having Burroughs, supposedly his nephew, find his late uncle's written account of his time there following his death and then flashing back to it. Stanton in response considered that "lazy". He told them "If I do that, then thirty minutes in I'm going to have to stop the film to explain the war, and Dejah, and who everyone is, and we're going to have even bigger problems". They compromised by beginning the movie with the battle on Mars, and then the Zondangans getting the nanofoam gun from the Therns. That shift necessitated 18 new scenes, for which Disney agreed to a reshoot.[31]

Cinematography and visual effects

[edit]The film was shot in the Panavision anamorphic format on Kodak 35 mm film stock. "I try very hard to persuade whomever I'm working with to allow me to shoot on film, and to shoot anamorphically," Mindel told ICG, the magazine of the International Cinematographers Guild. "It's the most pure, high-definition way of capturing a scene, short of Showscan or IMAX".[41]

But Mindel also liked the flaws in that process. Older Panavision lenses have imperfections and aberrations, and "At a purely organic level, the light does unmanageable things when it hits an aberration", he said. "An unquantifiable magic happens, and I love that!" That unpredictability, and the effect on the film's texture and grain, gave Mindel images he hoped would "[feel] inherently realistic in spite of the fantastical creatures and the extensive digital-visual-effects technology behind them". For John Carter he used Panavision's Primo and C-Series anamorphic lenses and ATZ and AWZ zoom lenses, with Kodak's Vision3 500T Color Negative 5219 and 200T 5213 stock.[41]

Shooting with a 3D release in mind was considered but dropped over a year before principal photography. The camera crew and effects specialists viewed Disney's Alice in Wonderland, where space on the set was planned with the 3D release in mind. They realized that the processes used for that film would be outdated before they could expect that they would start John Carter, so there was no point in planning for 3D; Stanton also believed that would be too much to deal with while shooting in any event. Mindel said that was "a huge relief".[41]

Work on the visual effects had begun earlier, in 2009, before the release of Avatar, which revolutionized the field. The effects team doing proof-of-process tests realized when that movie came out that John Carter would require extensive use of all the techniques that Avatar had pioneered, and would go where that film had not with many more interactions between human actors and CGI characters. Peter Chiang, the film's visual effects supervisor at Double Negative in London, wrote a production bible for the latter that described how each character should be composed and framed. Bruce McCleery, the second unit's director of photography, said that bible was especially useful for scenes blending humans and CGI characters. "Working that out was much more complex than it sounds".[41]

Shooting the airship battle on a London soundstage required extensive preproduction work. Mindel and the lighting crew started work designing the lighting rig for that scene long before shooting started. They shared their work with the effects teams, which used Lidar to map it, as it did for every set. The sets housed the full 110-foot (34 m) airship models, mounted on gimbals with green screen on all sides. Ultimately, to stage an aerial battle with light-based weapons where the ships maneuver to block the sunlight that powers their opponents' craft, the lighting crew used 120 Spacelights, 15 Dino light banks, flashing lights and a crane mounted with soft lights and green screens that could fill in ambient light from the film's sky.[41]

Once production moved to the Utah desert, the weather added its own challenges. Heavy winds brought frequent sandstorms, forcing many on location to work while wearing goggles and sometimes burnooses. Mindel wanted the film to take advantage of these conditions as much as possible, although he had to tone it down slightly so the effects teams could do their job. "All the uncontrollable natural phenomena did give the film a visceral, unpredictable quality, and contributed to its unique, idiosyncratic texture," McCleery said.[41]

Reshoots

[edit]Before the formal reshoot, which took place throughout September in the Los Angeles neighborhood of Playa Vista,[41] Stanton told The New Yorker he had done some smaller-scale reshooting focusing on additional dialogue for some characters in order to address the issues the preview had raised. In London, he shot scenes where West, as Sab Than, clarified the Therns' goals. Back in Los Angeles, Kitsch and Collins filmed Carter's proposal scene. Then Stanton went back to London to film Strong's side of the conversation with Sab Than.[31] Stanton denied assertions that he had gone over budget and stated that he had been allowed a longer reshoot because he had stayed on budget and on time.[42]

Stanton reshot much of the movie twice, far more than was common in live action filmmaking at that time. He attributed that to his animation background.[25] "The thing I had to explain to Disney was, 'You're asking a guy who's only known how to do it this way to suddenly do it with one reshoot.'" he explained later. "I said, 'I'm not gonna get it right the first time, I'll tell you that right now.'"[24] Stanton often sought advice from people he had worked with at Pixar on animated films (known as the Braintrust) instead of those with live-action experience working with him.[31]

Stanton also was quoted as saying, "Is it just me, or do we actually know how to do this better than live-action crews do?"[31] Rich Ross, Disney's chairman, successor to Dick Cook, who had originally approved the film for production,[b] came from a television background and had no experience with feature films. The studio's new top marketing and production executives had little more.[25]

The New Yorker writer Tad Friend visited the set during the reshoot and wrote an article about it, noting that it was "unusually extensive (and expensive)". Collins and Kitsch both made comments on the record about the reshoot that seemed defensive; Stanton told Friend not only that if it had been up to him he would have insisted on a second reshoot but that reshoots should be "mandatory".[31] It has subsequently been suggested that this article began the media narrative that John Carter was in serious trouble,[35] as conventional Hollywood wisdom held that any reshoot was an indicator of a troubled production.[44]

Collins believes that the reshoot was detrimental for her character. Originally filmed as a strong, independent warrior, the scenes added, such as those with her father, made her seem more vulnerable; and scenes like those in which she had slapped Carter were cut. She believes the studio wanted a softer take on Thoris and was reduced to asking Stanton every day what would work with that and just doing it.[35]

After the reshoot, considerable work remained in post-production on Stanton's first cut, reportedly almost three hours long.[45] There were many effects and CGI shots to finish. Stanton recalls that "[t]here were more animated shots in what was left to do on Carter than an entire animated feature". Animating the Tharks, especially in large numbers during battle scenes, proved particularly challenging; the software had to be upgraded for it, and as one animator recalls, work scenes sometimes took three hours to open. Many of those working on the CGI were particularly appreciative of Stanton, since due to his background he had considerable expertise in the area and made himself more available than directors of such films usually are.[35]

Marketing

[edit]John Carter's marketing has been called "one of the worst marketing campaigns in movie history". The filmmakers believe that the decisions made in marketing the film were the primary reason for its failure.[16][17][18] A new studio executive team with minimal experience in that side of the business was in charge, and not as emotionally invested in its success as the filmmakers had been. Furthermore, unbeknownst to them, Disney CEO Robert Iger had already begun talks with George Lucas about buying Lucasfilm and the Star Wars franchise, eliminating any incentive the company had to launch a successful competing film franchise.[35]

The head of Walt Disney Studios Marketing during the production was M T Carney, an industry outsider who previously ran a boutique marketing firm in New York[46] with no previous experience marketing movies.[35] Stanton often rejected marketing ideas from the studio, according to those who worked on the film.[47] His ideas were used instead, and he ignored criticism that using a cover version of Led Zeppelin's 1975 song "Kashmir" in the trailer released in conjunction with an ad aired during that year's Super Bowl would make it seem less current to the contemporary younger audiences the film sought.[25]

He also chose billboard imagery that failed to resonate with prospective audiences, and put together a preview reel that did not get a strong reception from a convention audience.[25] Stanton said, "My joy when I saw the first trailer for Star Wars is I saw a little bit of almost everything in the movie, and I had no idea how it connected, and I had to go see the movie. So the last thing I'm going to do is ruin that little kid's experience".[48] Following the death of Steve Jobs, Stanton dedicated the film in his memory.[49][c]

Effect of other 2011 films' box office

[edit]Disney reportedly grew more concerned about the film's prospects after the 2011 failure of the Lionsgate Films' remake of Conan the Barbarian. Like John Carter, it was based on a popular fantasy franchise that had during the 1980s been adapted into successful films starring Arnold Schwarzenegger. Lionsgate's version had cost $90 million and starred Jason Momoa. Chabon recalls reading a Quora post by one of its screenwriters, Sean Hood, about how he dealt with the movie's failure, and for the first time worrying about the possibility that John Carter could suffer the same fate.[35]

Cowboys & Aliens, released in July, also had an effect on John Carter. It too had science fiction and western elements, and did not fare well commercially. That was taken as indicating that contemporary audiences were not interested in westerns, or any film set in the American past, so those elements would be downplayed in the trailers and other marketing for John Carter.[50]

One of Disney's own recent big-budget franchise films was also adding to executives' anxieties about John Carter. The May 2011 release of Pirates of the Caribbean: On Stranger Tides had done well at the box office, becoming the third highest-grossing film domestically that year and making over a billion dollars worldwide. However, the film's budget, exceeding $400 million by some estimates, made it the most expensive film ever produced.[51] Its profits were thus lower than a film that popular might have been expected to generate, making Disney fear the same could happen with John Carter. By the time of the reshoot four months after On Stranger Tides, it was reported that John Carter would have to make at least $700 million worldwide, more than twice its escalating production costs, to justify a sequel.[31]

July 2011 preview screening

[edit]Initially expectations of the film's commercial success were high. The studio held a sneak preview in mid-2011, before the reshoot, in Portland, Oregon. Stanton, who had been diagnosed with high-functioning attention deficit hyperactivity disorder early in the process of writing the script, was so nervous he took lorazepam not just on the flight there but before the preview. Four Disney executives were in attendance to watch the reactions of 400 filmgoers and read their opinions afterwards. The audience reactions seemed to indicate that audiences were engaged with the film and laughed when they were supposed to, which relaxed Stanton.[31]

Afterwards, many of them rated the film as "very good" or "excellent", for an average audience approval rating of 75 percent, which pleased the studio. Carney said that that number could probably be rounded up to 80, reflecting work that had yet to be done. According to the preview cards, that work would also include improving the pacing of the film's second act, making the motivations of the Therns clearer, and developing the relationship between Carter and Thoris so that their wedding at the end was not so much of a surprise.[31]

Title changes

[edit]The film's title was a major issue; there are several accounts of who decided to change it and why. It is largely based on the first book of the series, A Princess of Mars, but was originally titled John Carter of Mars.[d] Stanton changed the title to that from the book's title early in 2011, "because not a single boy would go". Later he removed "of Mars" to make it more appealing to a broader audience, calling the film an "origin story ... about a guy becoming John Carter of Mars".[53] Disney also reportedly believed that the sex appeal of the popular Kitsch being shirtless throughout the movie would draw women to see the film. Since women are believed by Hollywood to be averse to science fiction, in this account, "Mars" was excised from the title.[35]

Stanton planned to keep "Mars" in the title for the proposed future films in the series.[53] Kitsch said the title was changed to reflect the character's journey, as John Carter would become "of Mars" only in the film's last few minutes.[54] Former Disney marketing president Carney has also been blamed for suggesting the title change.[46]

Another reported explanation for the name change was that Disney had suffered a significant loss in March 2011 with Mars Needs Moms; Carney reportedly conducted a study which noted recent movies with the word "Mars" in the title had not been commercially successful.[55] Chabon responds that all those films were poorly regarded by critics.[35][e]

Despite the name change, some hints of the original title remain. Some promotional materials used the stylized "JCM" logo, and at the end of the film is a title card with "John Carter of Mars". The marketing team had yielded to Stanton on that, and he explained that "it means something by the end of the movie, and if there are more movies I want that to be what you remember".[35]

After the film's release and subsequent failure, the truncated title was seen as part of the problem. "What the hell is John Carter? What's the film about?" asked Peter Sealey, former marketing president at Columbia, told the Los Angeles Times. " I don't know who John Carter is. You've got to make that clear".[56] Stanton reportedly believed there was enough awareness of the books that this would not be a problem, to which another marketing executive responded, "People don't say, 'I know what I'll be for Halloween! I'll be John Carter!'"[16]

Trailers

[edit]| Trailers | |

|---|---|

| |

The film's teaser trailer released in August 2011 was also seen as poor marketing. It relied largely on visual imagery from the film, without saying much about the creators and their previous accomplishments,[f] or Burroughs's work and how it had influenced later science fiction universes like Star Wars. There were few effects and little action; Stanton has denied a rumor that that was because he did not have enough finished effects shots to use.[35] Disney executives have faulted Stanton for this, since his success at Pixar allowed him to demand and get control over John Carter's trailers.[17]

They reportedly strongly implored him to listen to their suggestions and he refused. "This is one of the worst marketing campaigns in the history of movies," a former studio marketing chief complained to Vulture shortly before the film opened. "It's almost as if they went out of their way to not make us care". After the full trailer, and the Super Bowl ad derived from it seemed similarly bland,[g] enough for Kitsch to publicly concur with criticisms of the film's marketing campaign,[17] a fan group online put out a competing trailer meant to address the official one's deficiencies.[35] During February 2012, new television ads emphasizing story points were launched, and a similarly cut trailer was attached to Act of Valor.[43]

Early 2012

[edit]After several weeks away from her office, Carney left at the beginning of 2012,[58] with four years remaining on her contract,[35] to be replaced by Ricky Strauss, former president of Participant Media,[h] for the beginning of the period immediately preceding the film's release when promotional efforts become more intensive. He committed to spending over $100 million to that end.[43] Sealey called the change in marketing leadership "[t]he worst thing that can happen to a movie" as it adversely affects the morale of the cast and crew, who often have to promote the film personally in the media.[56]

Disney moved the film's release up to early March 2012 from June,[12] giving it two box office weekends before Lionsgate's The Hunger Games, widely expected to do very well and compete for the same audience, came out.[60] As that date approached, the usual aspects of Disney's marketing pushes for big-budget tentpole films were absent. There were no large merchandise displays in the company's online and retail stores, nor at big-box stores like Target.[i] Nor were there prominently placed ads in the company's theme parks, or coverage on Disney-owned media such as the ABC broadcast network or Disney Channel.[35] "It needs to feel like an event, and right now it doesn't feel like an event," an unnamed marketing expert told The Hollywood Reporter.[43]

Instead, the company tried some alternative marketing approaches. Stanton gave a TED talk on storytelling, that had a short scene from John Carter as an example of one of his points.[61] While that was seen as effective, some other promotions, such as an "Are You The Real John Carter?" contest, in which men who could prove that was their real name were encouraged to enter a contest where winners would be invited to a special fan screening, were not.[35]

As the premiere date neared, some of the filmmakers were unaware of the negative press coverage already attached to the movie. Mindel and Stanton admitted later that they were somewhat oblivious due to largely being in contact only with those whom they had been working with in post-production. Collins said those who worked for her and followed media coverage kept that information from her.[35]

Dafoe, on the other hand, was aware that the media were lowering the public and the industry's expectations for the film: "[M]y recollection was that even before it was released, there were grumblings about it ... everything from the name change to regime change to poor publicity. But I remember before the movie was even seen, people were counting it out".[35]

Poor tracking

[edit]Tracking data, the results of long-term surveys of likely filmgoers to judge their interest in seeing an upcoming film upon its release, with a prediction of its opening weekend box office, for John Carter was returned to Disney in mid-February and shared both within and without the company. Nikki Finke reported in Deadline Hollywood that the numbers pointed to a serious failure. Barely half the likely audience was aware of the film, 27 percent said they were interested in seeing it, and 3 percent said it would be their first choice that weekend.[60]

An executive at a rival studio told Finke that demographic data with the "shocking" tracking for such a costly film showed that women in particular "have flat out rejected the film" and expected "the biggest writeoff of all time". Finke reported that she had heard estimates of a loss around $100 million, but allowed that soft numbers had been widely expected as Disney's in-house surveys had been showing them for some time. Disney told her that the Super Bowl ad had given the film an expected "pop of awareness" and the studio remained committed to a full marketing push before the release.[60]

Chabon says that on the eve of the premiere, he was in a hotel down the street and Disney's marketing department was showing the team the latest tracking. "None of it was good", he recalled. Despite doubts and awareness of previous occasions when such dire forecasts had been wide of the mark, "[w]e just all kind of knew at that point it was going to be bad. It was not going to go well".[35]

Just before the film was released, an Evercore analyst who followed Disney more than doubled his estimate of the likely loss, to $165 million, because of the tracking. Other analysts had similarly revised their estimates upward, to $100 million or more.[62]

Premiere

[edit]Disney scheduled the late February premiere for Regal's LA Live Theatre in downtown Los Angeles, rather than the El Capitan Theatre in Hollywood, which it owned and had renovated extensively. The choice of venue has been described as "odd", since Disney had held most of its premieres, particularly of big-budget franchise films, there since the renovation. In a news release announcing the premiere, Disney highlighted that the movie would be shown in 3D on a 70-foot (21 m) screen to an audience of 800 in three theaters, ranging from the cast and crew and company executives to critics, D23 members and winners of contests.[35]

Collins, still unaware of the negative media perception of the film, recalls walking in and going down the red carpet behind Kitsch. She saw Rich Ross call him over and whisper something in his ear, after which he suddenly stepped back. When she caught up to Kitsch, she asked what Ross had told him that had so affected him. " 'It's a disaster.' He just told me, 'It's going to be a fucking disaster.'"[35]

Post-release criticisms

[edit]In the LA Times the week after the release, industry insiders suggested two reasons the film might have struggled to succeed with audiences regardless of how well it had been made or marketed. One was that more recent franchises, such as Star Wars, that had derived and borrowed from Burroughs' original concepts in the century since it had been written had exhausted the potential for audiences to be enthralled by any modern adaptation of his work. Jacks, the producer who had tried to make a film of the work in the early 2000s, recalled having given director Robert Zemeckis the novels in order to interest him in the project. "I don't think so," Zemeckis told him after reading them. "George [Lucas] has really plundered these books".[56]

Another industry marketing person, speaking anonymously, told the Times that modern audiences have a "cognitive dissonance" problem with films set on Mars based on older works. At the time Burroughs wrote, little was known about conditions on Mars, allowing an author to fill in those gaps with invented details. However, modern audiences know from the many actual uncrewed missions to Mars that that planet is uninhabitable and apparently devoid of life. "You're not able to sell [Burroughs's vision]", he said.[56]

Two of the film's supporting cast members weighed in later in the year on the role marketing played in its poor box office performance in separate interviews with The A.V. Club. In July, Cranston called its cool reception "unwarranted" and blamed it on TV stations around the country focusing on commercial news about how John Carter had underperformed and not even won its opening weekend rather than offering a review of the film, leading viewers to make their decisions about what movie to see on that basis. "Why is it all of a sudden important for average Americans to know how much money a movie made at the box office?"[63]

"I don't know why it's done so badly, or that it's perceived as being the [biggest] flop in Hollywood history", West said four months later. "It's not that bad at all". He defended Stanton and the film, calling the former "a fucking genius" and noting that the reviews actually had not been very bad. West disclosed also that after production, in 2010, he had seen a marketing plan for the film that was never used, which he believed would have been much more effective than what Disney chose to do.[64]

In 2020 Screen Rant's Kayleigh Donaldson reiterated the earlier arguments that Stanton's Pixar-based filmmaking process had unnecessarily increased costs, and that the film's ensuing bloated production budget made it harder to be profitable, as had been the case with Pirates of the Caribbean: On Stranger Tides. She noted that all but one of the 10 most expensive films ever made had been made in the last decade, and all but one of those nine had been Disney productions. "This is now the status quo for blockbuster cinema, an era of too-big-to-fail filmmaking that is almost exclusively reliant on international grosses just to break even". Of those eight Disney films, John Carter was the only one not part of an existing franchise. That large budget was necessary to faithfully and credibly replicate Burroughs's vision onscreen, but at the same time audiences were accustomed enough to expensive CGI and effects spectacles that that alone could not be expected to impress them.[65]

Donaldson also criticized the titling, noting that the early decision to not use the book title, A Princess of Mars, "raised a lot of questions over who Disney wanted to sell the movie to", implying that the studio feared that men might not be interested in a movie with "Princess" in the title, despite Disney's own experience to the contrary with its many princess movies. Stripping it down to just John Carter "robbed the movie of its identity ... as a title [it] conveyed nothing to potential audiences about the movie they were being sold".[65] Henry Hards, a writer at Giant Freakin Robot, agreed in 2023, calling John Carter "the most generic title possible ... Don't tell me that [A Princess of Mars] wouldn't have looked a lot better on a movie poster".[66]

Stanton's stated reason for the latter move, that the narrative is about how John Carter becomes John Carter of Mars, also, to Donaldson, points to another problem that has beset other films adapted from series with multiple books. "In an effort to play catch-up to a franchise that spent years developing its intricately woven multiple narratives, many studios tried to do the work of three or four movies in one", she wrote. "This resulted in a lot of franchise non-starters because audiences had little interest in films that existed solely to set up a bunch of sequels for a property they didn't care about". Among these she included Artemis Fowl, Robin Hood, and King Arthur: Legend of the Sword. Likewise with John Carter, the realization of Barsoom onscreen "wasn't enough to sustain a movie and didn't entice enough people to invest in a trilogy that would never see the light of day".[65]

Donaldson argued that in addition to being overtaken by works influenced by it, the Carter franchise was no longer popular enough to sustain an expensive film franchise by 2012, a century after the first book was published, an issue unintentionally highlighted by the use of "Kashmir" in the trailer. There still were fans, she conceded, but "[n]ame recognition alone does not make a movie hit. Just ask the most recent Tarzan reboot for evidence of that, or Disney's own attempt to make The Lone Ranger a 21st century action favorite", referring to the studio's 2013 effort, which also failed at the box office.[65]

Hards also said his complaints about the title led to another area where the marketing failed the film: its posters. "They work, but they also highlight the biggest problem the movie has. They all scream family-friendly". Burroughs's books, by contrast, depict "a violent barbarian warrior-style ... world in which women don't wear clothes", or at least that was how they had been depicted on older covers of the books, pointing to one on which Dejah is shown in a very scanty bikini. "Martian women are strong, confident, and have no body shame. They don't need clothes. Or at least that's the premise Burroughs presents as the reality of life on Mars". The franchise was "an R-rated, Conan-style story set in space" and should have been filmed that way, although Hards allowed that might alienate early 20th-century, even though it might have seemed liberating when Burroughs wrote the books.[66]

Music and soundtrack

[edit]In February 2010, Michael Giacchino revealed in an interview he would be scoring the film.[67][68] A year and a half later, in his New Yorker article, Friend documents accompanying Stanton on a visit to Giacchino where they discuss the movie's score and how it relates to the narrative. Stanton had put in the scratch music, the temporary music used to show what mood he wanted the actual score to reflect, himself rather than delegating that task to an editor as is commonly done. He told the composer that he wanted the music to reflect the two distinct plans driving the plot: Carter's and the Therns'. Stanton also said he wanted the music for Carter to change in a way that reflected his slow acceptance of himself as John Carter of Mars.[31]

Stanton had used music from Perfume for the Therns; he wanted something similarly choral. With the opening voiceover and battle footage, he had put music from Syriana that sounded "dire and Middle Eastern and forlorn, like a culture clinging to its nobility". He suggested something similar to Giacchino as the "Mars theme", but advised against eventually merging it with Carter's theme. "[J]ust because you're master of the high seas doesn't mean you can't have a separate theme for the ocean". Giacchino agreed but suggested a different merger, doing the Mars theme chorally near the end of the film, to accentuate the Therns' apparently inevitable takeover of the planet, an idea Stanton eagerly accepted.[31] Walt Disney Records released the soundtrack on March 6, 2012, three days before the film's release.

Release

[edit]Theatrical run

[edit]John Carter was released theatrically in the United States by Walt Disney Studios Motion Pictures.[2] The original film release date was June 8, 2012. In January 2011, Disney moved the release date up three months to March 9 of that year.[10][69][70] A teaser trailer for the film premiered on July 14 and was shown in 3D and 2D with showings of Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows – Part 2; the official trailer premiered on November 30. On February 5, 2012, an extended commercial promoting the movie aired during the Super Bowl,[57] and the day before the game, Stanton, a Massachusetts native, held a special screening of the film for both the team members and families of the New England Patriots and New York Giants, the competing teams.[71]

Home media

[edit]Walt Disney Studios Home Entertainment released John Carter on Blu-ray, DVD, and digital download on June 5, 2012. The home media release was made available in three different physical packages: a four-disc combo pack (1 disc Blu-ray 3D, 1-disc Blu-ray, 1 DVD, and 1-disc digital copy), a two-disc combo pack (1 disc Blu-ray, 1 disc DVD), and one-disc DVD. John Carter was also made available in 3D High Definition, High Definition, and Standard Definition Digital.[clarification needed] Additionally, the home media edition was available in an On-Demand format. The Blu-ray bonus features include Disney Second Screen functionality, "360 Degrees of John Carter", deleted scenes, and "Barsoom Bloopers". The DVD bonus features included "100 Years in the Making", and audio commentary with filmmakers. The High Definition Digital and Standard Definition Digital versions both include Disney Second Screen, "Barsoom Bloopers", and deleted scenes. The Digital 3D High Definition Digital copy does not include bonus features.[72] In mid-June, the movie topped sales on both the Nielsen VideoScan First Alert sales chart, which tracks overall disc sales, and Nielsen's dedicated Blu-ray Disc sales chart, with the DVD release selling almost a million copies making $17 million and Blu-ray and 3-D releases selling almost as many copies making $19.2 million, for a combined total of $36.3 million in its first week alone.[73][74]

Reception

[edit]Box office

[edit]Although the film grossed nearly $300 million worldwide, it lost a considerable amount of money due to its cost. At the time of its release, Disney claimed the film's production budget was $250 million, although tax returns released in 2014 revealed its exact budget was $263.7 million after taking tax credits into account.[75] Before the film opened, analysts predicted the film would be a huge financial failure due to its exorbitant cost combined with production and marketing costs of $350 million,[76] with Paul Dergarabedian, president of Hollywood.com, noting "John Carter's bloated budget would have required it to generate worldwide tickets sales of more than $600 million to break even ... a height reached by only 63 films in the history of moviemaking".[77] Within two weeks of its release, Disney took a $200 million writedown on the film, ranking it among the biggest box-office bombs of all time.[76][j] Two months after the release, the Walt Disney Company released a statement on its earnings attributing the $161 million decline in the operating income of its Studio Entertainment division to a loss of $84 million in the quarter ending March 2012 "primarily" due to the performance of John Carter and the associated cost write-down.[79]

Domestic

[edit]On March 9, 2012, John Carter opened domestically in over 3,500 theaters, taking in almost $10 million, the highest grosses of any film released that day.[80][81] It was the only time period for which that would be true. The following day, The Lorax, the previous weekend's box office winner,[82] which had lost that night to John Carter only by around $300,000, reasserted its primacy, grossing $18 million even as Disney's film improved to $12.3 million.[83] The Lorax went on to win the weekend,[84] with $38.8 million to John Carter's $30.1 million, which still made it the highest-grossing new release that weekend, easily beating Silent House and A Thousand Words.[85]

Domestically, both The Lorax and John Carter were displaced by the next weekend's winner, the newly released 21 Jump Street, which easily outgrossed both. John Carter stayed in all its theaters, but revenues dropped by more than half from the previous weekend, to $13 million.[86] On the film's third weekend, its theater count dropped by approximately 500 as The Hunger Games arrived in theaters with a $152.5 million opening weekend; John Carter's receipts again more than halved, down to $5 million.[87]

Throughout April, grosses and theaters continued to decline. Following that year's Easter weekend, it dropped out of the box office top 10, by which point it was in less than 500 theaters and earning less than a million dollars. John Carter experienced a slight resurgence on the first weekend of May, coinciding with the release of Disney's other expected tentpole for early 2012, The Avengers, a Marvel film based on its popular comic franchise, when its theater count nearly doubled and grosses rose to $1.5 million, the last weekend they would reach seven figures. Disney again increased its theater count two weeks later,[88] when Battleship, also starring Kitsch, was released.[89] But it did not boost the grosses, which steadily declined as it left more and more theaters through the end of June.[88]

International

[edit]Outside North America, it topped the weekend chart, opening with $70.6 million.[90] Its highest-grossing opening was in Russia and the Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS), where it broke the all-time opening-day record ($6.5 million)[91] and earned $16.5 million during the weekend.[92] The film also scored the second-best opening weekend for a Disney film in China[93] ($14.0 million).[94] It was in first place at the box office outside North America for two consecutive weekends.[95]

John Carter grossed $73.1 million in North America and $211.1 million in other countries, for a worldwide total as of June 28, 2012[update], of $284.1 million.[96] It had a worldwide opening of $100.8 million.[97] Its highest-grossing areas after North America are China ($41.5 million),[98] Russia and the CIS ($33.4 million), and Mexico ($12.1 million).[99]

Critical response

[edit]One week before the film's release, Disney removed an embargo on reviews of the film.[100] The film holds a 52% rating at the film review aggregator website Rotten Tomatoes based on 239 reviews, with an average rating of 5.80/10. The consensus reads: "While John Carter looks terrific and delivers its share of pulpy thrills, it also suffers from uneven pacing and occasionally incomprehensible plotting and characterization".[101] At Metacritic, which assigns a weighted average out of 100 to critics' reviews, the film holds a score of 51 based on 43 reviews, indicating "mixed or average reviews".[102] Audiences polled by CinemaScore gave the film an average grade of "B+" on an A+ to F scale.[103]

Todd McCarthy of The Hollywood Reporter wrote, "Derivative but charming and fun enough, Disney's mammoth scifier is both spectacular and a bit cheesy".[104] Glenn Kenny of MSN Movies rated the film 4 out of 5 stars, saying, "By the end of the adventure, even the initially befuddling double-frame story pays off, in spades. For me, this is the first movie of its kind in a very long time that I'd willingly sit through a second or even third time".[105] Roger Ebert of the Chicago Sun-Times rated the film 2.5 out of 4 stars, commenting that the movie "is intended to foster a franchise and will probably succeed. Does John Carter get the job done for the weekend action audience? Yes, I suppose it does".[106] Dan Jolin of Empire gave the film 3 stars out of 5, noting, "Stanton has built a fantastic world, but the action is unmemorable. Still, just about every sci-fi/fantasy/superhero adventure you ever loved is in here somewhere".[107] Joe Neumaier of the New York Daily News gave the film 3 out of 5 stars, calling the film "undeniably silly, sprawling and easy to make fun of, [but] also playful, genuinely epic and absolutely comfortable being what it is. In this genre, those are virtues as rare as a cave of gold".[108]

... the movie is more Western than science fiction. Even if we completely suspend our disbelief and accept the entire story at face value, isn't it underwhelming to spend so much time looking at hand-to-hand combat when there are so many neat toys and gadgets to play with?

—Roger Ebert, writing for the Chicago Sun-Times[106]

Conversely, Peter Debruge of Variety gave a negative review, saying, "To watch John Carter is to wonder where in this jumbled space opera one might find the intuitive sense of wonderment and awe Stanton brought to Finding Nemo and WALL-E".[2] Owen Glieberman of Entertainment Weekly gave the film a D rating, feeling, "Nothing in John Carter really works, since everything in the movie has been done so many times before, and so much better".[109] Christy Lemire of The Boston Globe wrote that, "Except for a strong cast, a few striking visuals and some unexpected flashes of humor, John Carter is just a dreary, convoluted trudge – a soulless sprawl of computer-generated blippery converted to 3-D".[110] Michael Philips of the Chicago Tribune rated the film 2 out of 4 stars, saying the film "isn't much – or rather, it's too much and not enough in weird, clumpy combinations – but it is a curious sort of blur".[111] Andrew O'Herir of Salon.com called it "a profoundly flawed film, and arguably a terrible one on various levels. But if you're willing to suspend not just disbelief but also all considerations of logic and intelligence and narrative coherence, it's also a rip-roaring, fun adventure, fatefully balanced between high camp and boyish seriousness at almost every second".[112] Mick LaSalle of San Francisco Chronicle rated the film 1 star out of 4, noting, "John Carter is a movie designed to be long, epic and in 3-D, but that's as far as the design goes. It's designed to be a product, and it's a flimsy one".[113] A.O. Scott of The New York Times said, "John Carter tries to evoke, to reanimate, a fondly recalled universe of B-movies, pulp novels and boys' adventure magazines. But it pursues this modest goal according to blockbuster logic, which buries the easy, scrappy pleasures of the old stuff in expensive excess. A bad movie should not look this good".[114]

In the UK, the film was panned by Peter Bradshaw in The Guardian, gaining only 1 star out of 5 and described as a "giant, suffocating doughy feast of boredom".[115] The film garnered 2 out of 5 stars in The Daily Telegraph, described as "a technical marvel, but is also armrest-clawingly hammy and painfully dated".[116] BBC film critic Mark Kermode expressed his displeasure with the film commenting, "The story telling is incomprehensible, the characterisation is ludicrous, the story is two and a quarter hours long and it's a boring, boring, boring two and a quarter hours long".[117]

Accolades

[edit]| Organization | Award category | Nominee(s) | Result |

|---|---|---|---|

| ASCAP Awards | Top Box Office Films | Michael Giacchino | Won |

| Annie Awards[118] | Best Animated Effects in a Live Action Production | Sue Rowe, Simon Stanley-Clamp, Artemis Oikonomopoulou, Holger Voss, Nikki Makar and Catherine Elvidge | Nominated |

| Nebula Awards | Ray Bradbury Award for Outstanding Dramatic Presentation | Andrew Stanton, Mark Andrews and Michael Chabon | |

| Golden Trailer Awards[119] | Golden Fleece | Ignition Creative and Walt Disney Studios Motion Pictures | |

| International Film Music Critics Association Awards | Best Original Score for a Fantasy/Science Fiction/Horror Film | Michael Giacchino | Won |

| Film Music Composition of the Year – John Carter of Mars | Nominated | ||

| Saturn Awards | Best Special Effects | Chris Corbould, Peter Chiang, Scott R. Fisher and Sue Rowe |

Aftermath

[edit]Corporate

[edit]The film's failure led to the resignation of Rich Ross, the head of Walt Disney Studios, even though Ross had arrived there from his earlier success at the Disney Channel with John Carter already in development.[120] Ross theoretically could have stopped production on John Carter as he did with a planned remake of 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea, or minimized the budget as he did to The Lone Ranger starring Johnny Depp.[121] Instead, Stanton was given the production budget requested for John Carter, backed with an estimated $100 million marketing campaign that is typical for a tentpole movie but without significant merchandising or other ancillary tie-ins.[55] It was reported that Ross later sought to blame Pixar for John Carter, which prompted key Pixar executives to turn against Ross, who already had alienated many within the studio.[122]

In September 2014, studio president Alan Bergman was asked at a conference if Disney had been able to partially recoup its losses on The Lone Ranger and John Carter through subsequent release windows or other monetization methods, and he responded: "I'm going to answer that question honestly and tell you no, it didn't get that much better. We did lose that much money on those movies".[123]

Double Negative, the British visual effects house now known as DNEG, also saw its business adversely affected by the film's failure. According to its later head, Robyn Luckham, who worked extensively on John Carter, the goal of working on the film was to develop expertise in animating creatures, something they believed would be in demand in the near future. "[E]veryone got cold feet", he recalls. "We didn't have another big show like that for a long time. It was tough".[35]

Personal

[edit]The night after the premiere, Lynn Collins says she was at another event to promote the movie, when her manager at the time told her "you're just going to have to disappear for a while" due to the mounting perception of the film's failure. She felt it was sexist that as the film's female lead she should suffer for its failure while Kitsch went on to make Battleship,[k] another big-budget science fiction film that failed at the box office when it was released two months after John Carter. "I took a break and tried to figure out, up until then my career and my work, I really allowed it to define me", she later said. A year later she fired not just her manager but her entire representation.[35]

After the premiere, Stanton went back to New York City, where as he later told the LA Times he spent the next three weeks riding the subway, working on other scripts and reconnecting with his daughter and friends.[44] "I had to go into true 'Lost Weekend' to just purge myself" of empty nest syndrome, he said later.[35] He returned to Pixar, where his many longtime coworkers felt badly for him;[44] Iger had called him shortly after the premiere, quoting from Theodore Roosevelt's "Citizenship in a Republic" speech. "It was the best thing anybody could say at that moment and especially him", Stanton recalled. "It just made me all the more loyal to him after that, whatever they needed help with".[35]

Cancelled sequels

[edit]Prior to the film's release, the filmmakers reported that John Carter was intended to be the first film of a trilogy.[125] Producers Jim Morris and Lindsey Collins began work on a sequel based on Burroughs' second novel, The Gods of Mars.[126] However, the film's poor box office performance put plans for sequels into question.[127]

In June 2012 co-writer Mark Andrews said in an interview that he, Stanton, and Chabon were still interested in doing sequels: "As soon as somebody from Disney says, 'We want John Carter 2', we'd be right there".[128] Despite criticism and Disney's financial disappointment with the film, lead actors Taylor Kitsch and Willem Dafoe all showed strong support,[129][130][131] with Kitsch stating "I would do John Carter again tomorrow. I'm very proud of John Carter".[132]

In September 2012, Stanton announced that his next directorial effort would be Pixar's Finding Dory, and that the plan to film a John Carter sequel had been cancelled.[133] Kitsch later stated he would not make another John Carter film unless Stanton returns as director.[134] In a May 2014 interview, he added, "I still talk to Lynn Collins almost daily. Those relationships that were born won't be broken by people we never met. I miss the family. I miss Andrew Stanton. I know the second script was awesome. We had to plant a grounding, so we could really take off in the second one. The second one was even more emotionally taxing, which was awesome".[135] Stanton tweeted both titles and logos for the sequels that would have been made with the titles being Gods of Mars and Warlord of Mars.[14][15]

In October 2014, Disney allowed the film rights to the Barsoom novels to revert to the Burroughs estate.[136] In November 2016, Stanton stated, "I will always mourn the fact that I didn't get to make the other two films I planned for that series".[137]

Stanton's Gods of Mars setup

[edit]In 2022, on the film's 10th anniversary, Stanton shared with TheWrap how the sequel, Gods of Mars, would have begun ... with Collins reading the prologue narration as Dejah and, over a relevant montage, recounting the events of the first film. When she appeared diegetically, she would be shown telling it to an infant, Carthoris, her child by Carter. Tardos would then have come into the scene, telling Dejah to go to bed herself and he would put his grandchild to bed. When she left, Tardos would have been revealed to actually be Matai Shang, having shapeshifted to appear to be Tardos, and then after Shang kidnapping the child the opening credits would have begun.[35]

Following the credits, Stanton said, Carter would be seen in his funeral suit lying in the middle of the desert, and waking up. He would take off his jacket and start walking, as a thoat driven by a Thark slowly came in from the horizon. The driver would tell Carter he knew who he was and someone was looking for him. He would take Carter to Kantos Kan, who had been searching for Carter for a long time and was shocked to actually find him. Kan would explain to Carter "you have to get back to heal him".[35]

The audience, expecting a reunion, would then learn that some time had elapsed since the prologue. In the interim, Dejah would have disappeared as well, exploring the River Iss in hopes of finding Carter. Eventually it would have been revealed that the Therns took their child, which would have, as in the second of Burroughs' books and Beneath the Planet of the Apes, led to revelations that a technologically advanced race living beneath the surface was controlling the air and water supply to keep the planet alive. He implied he had written more, but that was as much as he was willing to reveal at that time.

Legacy

[edit]The film's two leads remain proud of the work they did and believe the film is better than its reputation. Kitsch, who has largely returned to television work following his two big-budget failures in 2012, told The Hollywood Reporter when 21 Bridges was released in 2019 that "I learned a ton on that movie. I honestly don't see it as a failure". He noted that fans in Europe still stopped him on the street and mentioned the movie, which he believed had also seen an uptick in viewership due to its recent availability on Netflix.[138]

Collins says it took some time for her to come to terms with the film and its effect on her career. Eventually, "[p]eople started reaching out to me and expressing to me how much the movie changed their life, how much the character inspired them and motivated them ... It's posterity forever. I will die, and people will still be seeing this movie". She came to realize that "a movie that is that polarizing is good no matter what, because that's what art is supposed to do".[35]

On the 10th anniversary of the film's release, The Hollywood Reporter's Richard Newby considered its longterm impact, observing that it "changed the film landscape, just not in the way anyone intended it to ... [It] was the moment Disney became the servant of sure bets, and Hollywood realized star power was truly gone. That was when we entered the age of name recognition, where familiar characters and concepts—Jedi, superheroes—became worth more than any actor's name".[139]

Decennial reassessment

[edit]Newby also argued that the film was better than its reputation. "What makes the box office failure so frustrating is that I don't believe this to be a case where anything could have been done differently", he wrote. "With the filmmaker, cast and technology at hand, John Carter was the best adaptation of A Princess of Mars that could have been made and seems will ever be made". He believed the film had actually improved on the book, giving its characters more depth and complexity.[139]

In a lengthy history of the film and an analysis of what contributed to its perceived failure on its 10th anniversary, TheWrap's Drew Taylor noted that for all the other discussions of what went wrong with John Carter,[35]

[f]ew discussed what went right. John Carter is a flawed movie, but it's also endlessly charming. It has a winsome, earnest spirit and the action sequences bristle with ingenuity and life. It's goofy, but it's also incredibly fun ... The design and the cinematography are genuinely stunning and Stanton takes big swings, like a scene of Carter massacring a race of evil Tharnks that is intercut with him burying his wife and child back on Earth. The movie really goes for it in a way that few blockbusters do. Stanton left it all on the field.

Three months later, /Film's Sandy Schaefer, after admitting that the film was "not without its faults", found John Carter was visually accomplished, "combin[ing] the gravelly textures of a Western with the striking aesthetic of a pulp sci-fi epic". Stanton had made better use of the film's budget than other directors of more recent tentpole films. Ironically, Schaefer concluded, "[a]fter a decade of superhero movies and Star Wars films, John Carter—itself adapted from source material that directly inspired so many of those things—comes across as more refreshing and less derivative now than when it was first released".[140]

Conversely, the passage of time had not helped the film for Gizmodo's Germain Lussier, who wrote, "I remember not hating the movie, but not particularly liking it either, and in the decade since release I've always wondered if John Carter had cult potential". Upon watching it again, he concluded it did not. "Ten years hasn't changed John Carter at all. It's still not an awful movie. There are a few really excellent things in there. But it's mostly just drawn out, uninteresting, and boring, in large part [due] to the whole thing feeling so derivative", since by 2012 aspects of the story that had been original to Burroughs's work had been reused in so many other works.[141]

Lussier also felt the "oceans of exposition between warring factions that are barely distinguishable" came at the expense of the movie's more successful action sequences, and apart from Dafoe and Morton he felt most of the Thark characters had little depth. "John Carter works, but it doesn't work well," Lussier concluded. "[T]his viewing made me realize that I doubt even 50 years will change how it feels".[141]

See also

[edit]- List of American films of 2012

- List of films set on Mars

- List of science fiction action films

- Sword and planet, subgenre of adventure science fiction in which most combat is with swords

Explanatory notes

[edit]- ^ Many contemporary filmmakers, by contrast, have preferred to film movies set on Mars in Jordan's Wadi Rum desert.[40]

- ^ By some accounts, Cook had greenlit John Carter before he or anyone in the studio's production division had read the script.[43]

- ^ "We didn't always agree on which direction to take every step of the way, but there was never serious contention," Stanton told the LA Times several months after the film's release, when asked about the film's marketing missteps. "The truth was everyone tried their very best to crack how to sell what we had, but the answer proved elusive."[44]

- ^ At the end of 2009, the independent film company The Asylum released Princess of Mars, a low-budget film released direct-to-DVD in the United States, the only other filmed adaptation of the Barsoom novels. Its marketing, intended to capitalize on Avatar's success that year, acknowledges that the story inspired that movie without mentioning Burroughs. Its story, like the pre-2005 versions of the script, had Carter (played by Antonio Sabàto Jr., (with Traci Lords as Dejah) as a modern-day U.S. soldier initially fighting in Afghanistan, and, notwithstanding its title, dispensed with the notion of Barsoom as Mars entirely, making it a planet light-years away. Since the novel is in the public domain and thus any filmmaker could adapt it, Stanton has referred to it as an inevitable "crappy knock-off". It was rereleased in 2012 as John Carter of Mars.[52]

- ^ Another person who had seen that research called it "the most ridiculous thing I've ever heard"[43]

- ^ Stanton took any references to his successful Pixar films out of the trailer to avoid the film being perceived as meant for children.[16]

- ^ Within the industry, the Super Bowl ad was seen as confirmation that the film was in serious trouble. "You know it's gotta be bad when they start breaking up the scenes and doing something conceptual for a Super Bowl spot", one executive at a competing studio said. "It's like, 'Guys, this is your Hail Mary?'"[50]

Collider's Adam Chitwood said he was "pleasantly surprised" by it, "but I'm still not convinced that the general audience has a handle on what the film's about."[57]

- ^ Strauss had never run a major studio's marketing division, which supposedly led to Steven Spielberg, whose DreamWorks films are distributed by Disney, angrily confronting Ross at the Critics' Choice Movie Awards dinner over why he was not consulted on the hiring.[59]