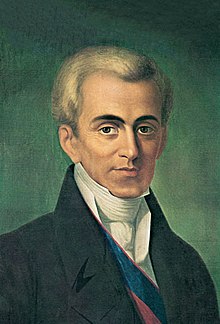

Ioannis Kapodistrias

Ioannis Kapodistrias | |

|---|---|

| Ιωάννης Καποδίστριας | |

Portrait by Dionysios Tsokos | |

| 1st Governor of Greece | |

| In office 20 January 1828 – 27 September 1831 (o.s.) | |

| Preceded by | Vice-gubernatorial Committee of 1827 Andreas Zaimis (as President of the Provisional Administration of Greece)[1] |

| Succeeded by | Augustinos Kapodistrias |

| Foreign Minister of Russia | |

| In office 1816–1822 Serving with Karl Nesselrode | |

| Monarch | Alexander I |

| Preceded by | Nikolay Rumyantsev |

| Succeeded by | Karl Nesselrode |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 10 February 1776 Corfu, Venetian Ionian Islands |

| Died | 27 September 1831 (aged 55) Nafplion, First Hellenic Republic |

| Political party | Russian Party |

| Relations | Viaros Kapodistrias (brother) Augustinos Kapodistrias (brother) |

| Alma mater | University of Padua |

| Signature | |

Count Ioannis Antonios Kapodistrias (Greek: Κόμης Ιωάννης Αντώνιος Καποδίστριας;[alt 1] c. 10[3][4][5] February 1776[6][2] –27 September 1831), sometimes anglicized as John Capodistrias, was a Greek statesman who was one of the most distinguished politicians and diplomats of 19th-century Europe.[7][8][9][10]

Capodistrias' involvement in politics begun as a minister of the Septinsular Republic in the early 19th century. He went on to serve as the foreign minister of the Russian Empire from 1816 until his abdication in 1822, when he became increasingly active in supporting the Greek War of Independence that broke out a year earlier.

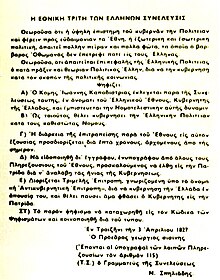

After a long and distinguished career in European politics and diplomacy, he was elected as the first head of state of independent Greece at the 1827 Third National Assembly at Troezen and served as the governor of Greece between 1828 and 1831. For his significant contribution during his governance, he is recognised as the founder of the modern Greek state,[11][12][13][14] and the architect of Greek independence.[15]

Background and early career

[edit]Ioannis Kapodistrias was born in Corfu, the most populous Ionian Island (then under Venetian rule) to a distinguished Corfiote family.[16] Kapodistrias's father was the nobleman, artist and politician Antonios Maria Kapodistrias (Αντώνιος Μαρία Καποδίστριας).[2][17] An ancestor of Kapodistrias had been created a conte (count) by Charles Emmanuel II, Duke of Savoy, and the title was later (1679) inscribed in the Libro d'Oro of the Corfu nobility;[18] the title originates from the city of Capodistria (now Koper) in Slovenia,[19][20] then part of the Republic of Venice and the place of origin of Kapodistrias's paternal family before they moved to Corfu in the 13th century, where they changed their religion from Catholic to Orthodox and they became completely hellenized.[21][22] His family's name in Capodistria had been Vitori or Vittori.[21][22] Origins of his paternal ancestors can also be found back in 1423 in Constantinople (with Victor/Vittor – or Nikiforos – Capodistrias). The coat of arms of the family, which today can be seen in Corfu, represented a cyan shield with a diagonial strip, containing three stars, and a cross.[23]

His mother was Adamantine Gonemis (Αδαμαντία "Διαμαντίνα" Γονέμη; Diamantina Gonemi), a countess,[17] and daughter of the noble Christodoulos Gonemis (Χριστόδουλος Γονέμης).[24] The Gonemis were a Greek[24][25][26] family originally from the island of Cyprus,[15] they had migrated to Crete when Cyprus fell to the Ottomans in the 16th century.[15] They then migrated to Epirus, near Argyrokastro, when Crete fell in the 17th century, finally settling on the Ionian island of Corfu.[15] The Gonemis family, like the Kapodistriases, had been listed in the Libro d'Oro (Golden Book) of Corfu.[27][28] Kapodistrias, though born and raised as a nobleman,[29] was throughout his life a liberal thinker and had democratic ideals.[9] His ancestors fought along with the Venetians during the Ottoman sieges of Corfu and had received a title of nobility from them.[7][30][31]

Kapodistrias studied medicine, philosophy and law at the University of Padua in 1795–97. When he was 21 years old, in 1797, he started his medical practice as a doctor in his native island of Corfu.[2][7][32][33][34] In 1799, when Corfu was briefly occupied by the forces of Russia and Turkey, Kapodistrias was appointed chief medical director of the military hospital. In 1802 he founded an important scientific and social progress organisation in Corfu, the "National Medical Association", of which he was an energetic member.

Some scholars have suggested that Kapodistrias had a romantic affair with Roxandra Sturdza, prior to her marriage with Count Albert Cajetan von Edling in 1816.[35]

Minister of the Septinsular Republic

[edit]

After two years of revolutionary freedom, triggered by the French Revolution and the ascendancy of Napoleon, in 1799 Russia and the Ottoman Empire drove the French out of the seven Ionian islands and organised them as a free and independent state – the Septinsular Republic – ruled by its nobles.[2] Kapodistrias, substituting for his father, became one of two ministers of the new state. Thus, at the age of 25, Kapodistrias became involved in politics. In Kefalonia he was successful in convincing the populace to remain united and disciplined to avoid foreign intervention and, by his argument and sheer courage, he faced and appeased rebellious opposition without conflict. With the same peaceful determination, he established authority in all the seven islands.

When Russia sent an envoy, Count George Mocenigo (1762–1839), a noble from Zakynthos who had served as Russian Diplomat in Italy, Kapodistrias became his protégé. Mocenigo later helped Kapodistrias to join the Russian diplomatic service.

When elections were carried for a new Ionian Senate, Kapodistrias was unanimously appointed as Chief Minister of State. In December, 1803, a less feudal and more liberal and democratic constitution was voted by the Senate. As minister of state, he organised the public sector, putting particular emphasis on education. In 1807 the French re-occupied the islands and dissolved the Septinsular Republic.[2]

Russian diplomatic service

[edit]In 1809 Kapodistrias entered the service of Alexander I of Russia.[36] His first important mission, in November 1813, was as unofficial Russian ambassador to Switzerland, with the task of helping disentangle the country from the French dominance imposed by Napoleon. He secured Swiss unity, independence and neutrality, which were formally guaranteed by the Great Powers, and actively facilitated the initiation of a new federal constitution for the 19 cantons that were the component states of Switzerland, with personal drafts.[37]

Collaborating with Anthimos Gazis, in 1814 he founded in Vienna the "Philomuse Society", an educational organization promoting philhellenism, such as studies for the Greeks in Europe.

In the ensuing Congress of Vienna, 1815, as the Russian minister, he counterbalanced the paramount influence of the Austrian minister, Prince Metternich, and insisted on French state unity under a Bourbon monarch. He also obtained new international guarantees for the constitution and neutrality of Switzerland through an agreement among the Powers. After these brilliant diplomatic successes, Alexander I appointed Kapodistrias joint Foreign Minister of Russia (with Karl Robert Nesselrode).

In the course of his assignment as Foreign Minister of Russia, Kapodistrias's ideas came to represent a progressive alternative to Metternich's aims of Austrian domination of European affairs.[36] Kapodistrias's liberal ideas of a new European order so threatened Metternich that he wrote in 1819:[36]

Kapodistrias is not a bad man, but honestly speaking he is a complete and thorough fool, a perfect miracle of wrong-headedness...He lives in a world to which our minds are often transported by a bad nightmare.

— Metternich on Kapodistrias, [36]

Realising that Kapodistrias's progressive vision was antithetical to his own, Metternich then tried to undermine Kapodistrias's position in the Russian court.[36] Although Metternich was not a decisive factor in Kapodistrias's leaving his post as Russian Foreign Minister, he nevertheless attempted to actively undermine Kapodistrias by rumour and innuendo. According to the French ambassador to Saint Petersburg, Metternich was a master of insinuation, and he attempted to neutralise Kapodistrias, viewing him as the only man capable of counterbalancing Metternich's own influence with the Russian court.

More than anyone else he possesses the art of devaluing opinions that are not his own; the most honourable life, the purest intentions are not sheltered from his insinuations. It is thus with profound ingenuity that he knew how to neutralize the influence of Count Capodistrias, the only one who could counterbalance his own

— French ambassador on Metternich, [36]

Metternich, by default, succeeded in the short term, since Kapodistrias eventually left the Russian court on his own, but with time, Kapodistrias's ideas and policies for a new European order prevailed.[36] He was always keenly interested in the cause of his native country, and in particular the state of affairs in the Seven Islands, which in a few decades' time had passed from French revolutionary influence to Russian protection and then to British rule. He always tried to attract his Emperor's attention to matters Greek. In January 1817, an emissary from the Filiki Eteria, Nikolaos Galátis, arrived in St. Petersburg to offer Kapodistrias leadership of the movement for Greek independence.[38] Kapodhistrias rejected the offer, telling Galátis:

You must be out of your senses, Sir, to dream of such a project. No one could dare communicate such a thing to me in this house, where I have the honour to serve a great and powerful sovereign, except a young man like you, straight from the rocks of Ithaka, and carried away by some sort of blind passion. I can no longer continue this discussion of the objects of your mission, and I assure you that I shall never take note of your papers. The only advice I can give to you to is to tell nobody about them, to return immediately where you have come from, and to tell those who sent you that unless they want to destroy themselves and their innocent and unhappy nation with them, they must abandon their revolutionary course and continue to live as before under their present government until Providence decrees otherwise.[39]

In December 1819, another emissary from the Filiki Eteria, Kamarinós, arrived in St. Petersburg, this time representing Petrobey Mavromichalis with a request that Russia support an uprising against the Ottomans.[40] Kapodistrias wrote a long and careful letter, which while expressing support for Greek independence in theory, explained that at present it was not possible for Russia to support such an uprising and advised Mavromichalis to call off the revolution before it started.[40] Still undaunted, one of the leaders of the Filiki Eteria, Emmanuel Xánthos arrived in St. Petersburg to again appeal to Kapodistrias to have Russia support the planned revolution and was again informed that the Russian Foreign Minister "...could not become involved for the above reasons and that if the arkhigoi knew of other means to carry out their objective, let them use them".[41] When Prince Alexander Ypsilantis asked Kapodistrias to support the planned revolution, Kapodistrias advised against going ahead, saying: "Those drawing up such plans are most guilty and it is they who are driving Greece to calamity. They are wretched hucksters destroyed by their own evil conduct and now taking money from simple souls in the name of the fatherland they do not possess. They want you in their conspiracy to inspire trust in their operations. I repeat: be on your guard against these men".[42] Kapodistrias visited his Ionian homeland, by then under British rule, in 1818, and in 1819 he went to London to discuss the islanders' grievances with the British government, but the British gave him the cold shoulder, partly because, uncharacteristically, he refused to show them the memorandum he wrote to the czar about the subject.[43]

In 1821, when Kapodistrias learned that Prince Alexander Ypsilantis had invaded the Ottoman protectorate of Moldavia (modern north-eastern Romania) with the aim of provoking a general uprising in the Balkans against the Ottoman Empire, Kapodistrias was described as being "like a man struck by a thunderbolt".[38] Czar Alexander, committed to upholding the established order in Europe, had no interest in supporting a revolt against the Ottoman Empire, and it thus fell to Kapodistrias to draft a declaration in Alexander's name denouncing Ypsilantis for abandoning "the precepts of religion and morality", condemning him for his "obscure devices and shady plots", ordering him to leave Moldavia at once and announcing that Russia would offer him no support.[38] As a fellow Greek, Kapodistrias found this document difficult to draft, but his sense of loyalty to Alexander outweighed his sympathy for Ypsilantis.[38] On Easter Sunday, 22 April 1821, the Sublime Porte had the Patriarch Grigorios V publicly hanged in Constantinople at the gate of his residence in Phanar.[44] This, together with other news that the Ottomans were killing Orthodox priests, led Alexander to have Kapodistrias draft an ultimatum accusing the Ottomans of having trampled on the rights of their Orthodox subjects, of breaking treaties, insulting the Orthodox churches everywhere by hanging the Patriarch and of threatening "to disturb the peace that Europe has bought at so great a sacrifice".[45] Kapodistrias ended his ultimatum:

"The Ottoman government has placed itself in a state of open hostility against the Christian world; that it has legitimized the defense of the Greeks, who would thenceforth be fighting to save themselves from inevitable destruction; and that in view of the nature of that struggle, Russia would find herself strictly obliged to offer them help because they were persecuted; protection, because they would be in need of it; assistance, jointly with the whole of Christendom; because she could not surrender her brothers in religion to the mercy of a blind fanaticism".[46]

As the Sublime Porte declined to answer the Russian ultimatum within the seven day period allowed after it was presented by the ambassador Baron Georgii Stroganov on 18 July 1821, Russia broke off diplomatic relations with the Ottoman Empire.[45] Kapodistrias became increasingly active in support of Greek independence from the Ottoman Empire, but did not succeed in obtaining Alexander's support for the Greek revolution of 1821.[2] This put Kapodistrias in an untenable situation and in 1822 he took an extended leave of absence from his position as Foreign Minister and retired to Geneva where he applied himself to supporting the Greek revolution by organising material and moral support.[2]

Return to Greece and the Hellenic State

[edit]

Kapodistrias moved to Geneva, where he was greatly esteemed, having been made an Honorary Citizen for his past services to Swiss unity and particularly to the cantons.[47] In 1827, he learned that the newly formed Greek National Assembly had, as he was the most illustrious Greek-born statesman in Europe, elected him as the first head of state of newly liberated Greece, with the title of Kyvernetes (Κυβερνήτης – Governor) for a seven-year term. A visitor to Kapodistrias in Geneva described him thus: "If there is to be found anywhere in the world an innate nobility, marked by a distinction of appearance, innocence, and intelligence in the eyes, a graceful simplicity of manner, a natural elegance of expression in any language, no one could be more intrinsically aristocratic than Count Capo d'Istria [Kapodistrias] of Corfu".[48] Under the aristocratic veneer, Kapodistrias was an intense workaholic, a driven man and "an ascetic bachelor" who worked from dawn until late at night without a break, a loner whom few really knew well.[48] Despite his work ethic, Kapodistrias had what the British historian David Brewer called an air of "melancholy fatalism" about him.[48] Kapodistrias once wrote about the cause of Greek freedom that "Providence will decide and it will be for the best".[48]

After touring Europe to rally support for the Greek cause, Kapodistrias landed in Nafplion on 7 January 1828, and arrived in Aegina on 8 January 1828.[49] The British didn't allow him to pass from his native Corfu (a British protectorate since 1815 as part of the United States of the Ionian Islands) fearing a possible unrest of the population. It was the first time he had ever set foot on the Greek mainland, and he found a discouraging situation there. Even while fighting against the Ottomans continued, factional and dynastic conflicts had led to two civil wars, which ravaged the country. Greece was bankrupt, and the Greeks were unable to form a united national government. Wherever Kapodistrias went in Greece, he was greeted by large and enthusiastic welcomes from the crowds.[50]

Kapodistrias asked the Senate to give him full executive powers and to have the constitution suspended while the Senate was to be replaced with a Panhellenion, whose 27 members were all to be appointed by the governor. All requests were granted.[51] Kapodistrias promised to call a National Assembly for April 1828. But, in fact, it took 18 months for the National Assembly to meet.[52]

He declared the foundation of the Hellenic State and from the first capital of Greece, Nafplion, he ushered in a new era in the country, which had just been liberated from centuries of Ottoman occupation. In September 1828, Kapodistrias at first restrained General Richard Church from advancing into the Roumeli, hoping that the French would intervene instead.[53] However, a French presence in Central Greece was refused and caused a veto by the British, who favoured the creation of a smaller Greek state, mainly in Peloponnese (Morea). The new British ambassador Edward Dawkins and admiral Malcolm asked from Kapodistrias to retreat the Greek forces to Morea, but he refused to do so and abandon central Greece.

Kapodistrias ordered Church and Ypsilantis to resume their advance, and by April 1829, the Greek forces had taken all of Greece up to the village of Kommeno Artas and the Makrinóros mountains.[53] Kapodistrias insisted on involving himself closely in military operations, much to the intense frustration of his generals.[53] General Ypsilantis was incensed when Kapodistrias visited his camp to accuse him to his face of incompetence, and later refused a letter from him under the grounds it was "a monstrous and unacceptable communication".[53] Church was attacked by Kapodistrias for being insufficiently aggressive, as the governor wanted him to conquer as much land as possible, to create a situation that would favor the Greek claims at the conference tables of London.[53] In February 1829, Kapodistrias made his brother Agostino lieutenant-plenipotentiary of Roumeli, with control over pay, rations and equipment, and a final say over Ypsilantis and Church.[53] Church wrote to Kapodistrias: "Let me ask you seriously to think of the position of a General in Chief of an Army before the enemy who has not the authority to order a payment of a sou, or the delivery of a ration of bread".[53] Kapodistrias also appointed another brother, Viaro, to rule over the islands off eastern Greece, and sent a letter to the Hydriots reading: "Do not examine the actions of the government and do not pass judgement on them, because to do so can lead you into error, with harmful consequences to you".[53]

Administration

[edit]

The most important task facing the governor of Greece was to forge a modern state and with it a civil society, a task in which the workaholic Kapodistrias toiled at mightily, working from 5 am until 10 pm every night.[54] Upon his arrival, Kapodistrias launched a major reform and modernisation programme that covered all areas. Kapodistrias distrusted the men who led the war of independence, believing them all to be self-interested, petty men whose only concern was power for themselves.[52] Kapodistrias saw himself as the champion of the common people, long oppressed by the Ottomans, but also believed that the Greek people were not ready for democracy yet, saying that to give the Greeks democracy at present would be like giving a boy a razor; the boy did not need the razor and could easily kill himself as he did not know to use it properly.[52] Kapodistrias argued that what the Greek people needed at present was an enlightened autocracy that would lift the nation out of the backwardness and poverty caused by the Ottomans and once a generation or two had passed with the Greeks educated and owning private property could democracy be established.[52] Kapodistrias's role model was the Emperor Alexander I of Russia, whom he argued had been gradually moving Russia towards the norms of Western Europe during his reign, but he had died before he had finished his work.[52]

Kapodistrias often expressed his feelings towards the other Greek leaders in harsh language, at one point saying he would crush the revolutionary leaders: "Il faut éteindre les brandons de la revolution".[52] The Greek politician Spyridon Trikoupis wrote: "He [Kapodistrias] called the primates, Turks masquerading under Christian names; the military chiefs, brigands; the Phanariots, vessels of Satan; and the intellectuals, fools. Only the peasants and the artisans did he consider worthy of his love and protection, and he openly declared that his administration was conducted solely for their benefit".[55] Trikoúpis described Kapodistrias as átolmos (cautious), a man who liked to move methodically and carefully with as little risk as possible, which led him to micro-manage the government by attempting to be the "minister of everything" as Kapodistrias only trusted himself to govern properly.[56] Kapodistrias alienated many in the Greek elite with his haughty, high-handed manner together with his open contempt for the Greek elites, but he attracted support from several of the captains, such as Theodoros Kolokotronis and Yannis Makriyannis who provided the necessary military force to back up Kapodistrias's decisions.[57] Kapodistrias, an elegant, urbane diplomat, educated in Padua and accustomed to the polite society of Europe formed an unlikely, but deep friendship with Kolokotronis, a man of peasant origins and a former klepht (bandit).[58] Kolokotronis described Kapodistrias as the only man capable of being president as he was not tied to any of the Greek factions, admired him for his concern for the common people who had suffered so much in the war, and liked Kapodistrias's interest in getting things done, regardless of the legal niceties.[58] As Greece had no means of raising taxes, money was always in short supply and Kapodistrias was constantly writing letters to his friend, the Swiss banker Jean-Gabriel Eynard, asking for yet another loan.[54] As a former Russian foreign minister, Kapodistrias was well connected to the European elite and he attempted to use his connections to secure loans for the new Greek state and to achieve the most favorable borders for Greece, which was being debated by Russian, French and British diplomats.[56]

Kapodistrias re-established military unity, bringing an end to the Greek divisions, and re-organised the military establishing regular Army corps in the war against the Ottomans, taking advantage also of the Russo-Turkish War (1828–29). The new Hellenic Army was then able to reconquer much territory lost to the Ottoman army during the civil wars. The Battle of Petra in September 1829 brought an end to the military operations of the war and secured the Greek dominion in Central Greece. He supported also two unfortunate military expeditions, to Chios and to Crete, but the Great powers decided that these islands were not to be included within the borders of the new state.

He adopted the Byzantine Hexabiblos of Armenopoulos as an interim civil code, he founded the Panellinion, as an advisory body, and a Senate, the first Hellenic Military Academy, hospitals, orphanages and schools for the children, introduced new agricultural techniques, while he showed interest for the establishment of the first national museums and libraries. In 1830 he granted legal equality to the Jews in the new state; being one of the first European states to do so.

Interested in urban planning for the destroyed Greek cities after the war, he assigned Stamatis Voulgaris to present a new urban plan for the cities of Patras, Argos, such as the Prónoia quarter in Nafplio as settlement for war refugees.

He introduced also the first modern quarantine system in Greece, which brought epidemics like typhoid fever, cholera and dysentery under control for the first time since the start of the War of Independence; negotiated with the Great Powers and the Ottoman Empire the borders and the degree of independence of the Greek state and signed the peace treaty that ended the War of Independence with the Ottomans; introduced the phoenix, the first modern Greek currency; organised local administration; and, in an effort to raise the living standards of the population, introduced the cultivation of the potato into Greece.[59] According to legend, although Kapodistrias ordered that potatoes be handed out to anyone interested, the population was reluctant at first to take advantage of the offer. The legend continues, that he then ordered that the whole shipment of potatoes be unloaded on public display on the docks of Nafplion, and placed it under guard to make the people believe that they were valuable. Soon, people would gather to look at the guarded potatoes and some started to steal them. The guards had been ordered in advance to turn a blind eye to such behaviour, and soon the potatoes had all been "stolen" and Kapodistrias' plan to introduce them to Greece had succeeded.[59]

Furthermore, as part of his programme, he tried to undermine the authority of the traditional clans or dynasties which he considered the useless legacy of a bygone and obsolete era.[60] However, he underestimated the political and military strength of the capetanei (καπεταναίοι – commanders) who had led the revolt against the Ottoman Turks in 1821, and who had expected a leadership role in the post-revolution Government. When a dispute between the capetanei of Laconia and the appointed governor of the province escalated into an armed conflict, he called in Russian troops to restore order,[citation needed] because much of the army was controlled by capetanei who were part of the rebellion.

Opposition, Hydriot rebellion and the Battle of Poros

[edit]

George Finlay's 1861 History of Greek Revolution records that by 1831 Kapodistrias's government had become hated, chiefly by the independent Maniates, but also by part of the Roumeliotes and the rich and influential merchant families of Hydra, Spetses and Psara. Their interests gradually were identified with the English policy and the most influential of them consisted the core of the so-called English Party.

The French stance, which was in general moderate towards Kapodistrias, became more hostile after the July Revolution in 1830.

The Hydriots' customs dues were the chief source of the municipalities' revenue, so they refused to hand these over to Kapodistrias. It appears that Kapodistrias had refused to convene the National Assembly and was ruling as a despot, possibly influenced by his Russian experiences. The municipality of Hydra instructed Admiral Miaoulis and Mavrocordatos to go to Poros and to seize the Hellenic Navy's fleet there. This Miaoulis did, the intention being to prevent a blockade of the islands, so for a time it seemed as if the National Assembly would be called.

Kapodistrias called on the British and French corps to support him in putting down the rebellion, but they refused to do so, and only the Russian Admiral Pyotr Ivanovich Ricord took his ships north to Poros. Colonel (later General) Kallergis took a half-trained force of Hellenic Army regulars and a force of irregulars in support. With less than 200 men, Miaoulis was unable to make much of a fight; Fort Heideck on Bourtzi Island was overrun by the regulars and the corvette Spetses (once Laskarina Bouboulina's Agamemnon) was sunk by Ricord's force. Encircled by the Russians in the harbor and Kallergis's force on land, Poros surrendered. Miaoulis was forced to set charges in the flagship Hellas and the corvette Hydra, blowing them up when he and his handful of followers returned to Hydra. Kallergis's men were enraged by the loss of the ships and sacked Poros, carrying off plunder to Nafplion.

The loss of the best ships in the fleet crippled the Hellenic Navy for many years, but it also weakened Kapodistrias's position. He did finally call the National Assembly but his other actions triggered more opposition and this led to his downfall.

Assassination

[edit]

In 1831, Kapodistrias ordered the imprisonment of Petrobey Mavromichalis, who had been the leader of the successful uprising against the Turks.[61] Mavromichalis was the Bey of the Mani Peninsula, one of the wildest and most rebellious parts of Greece – the only section that had retained its independence from the Ottoman Empire and whose resistance had spearheaded the successful revolution.[62] The arrest of their patriarch was a mortal offence to the Mavromichalis family, and on September 27, Petrobey's brother Konstantis and son Georgios Mavromichalis determined to kill Kapodistrias when he went to church that morning at the Church of Saint Spyridon in Nafplion.[63]

Kapodistrias woke up early in the morning and decided to go to church although his servants and bodyguards urged him to stay at home.[63] When he reached the church he saw his assassins waiting for him.[63] When he reached the church steps, Konstantis and Georgios came close as if to greet him.[56] Suddenly Konstantis drew his pistol and fired, missing, the bullet sticking in the church wall where it is still visible today. Georgios plunged his dagger into Kapodistrias's chest while Konstantis shot him in the head.[63] Konstantis was shot by General Fotomaras, who watched the murder scene from his own window.[64] Georgios managed to escape and hide in the French Embassy; after a few days he surrendered to the Greek authorities.[63] He was sentenced to death by a court-martial and was executed by firing squad.[63] His last wish was that the firing squad not shoot his face, and his last words were "Peace Brothers!"

Ioannis Kapodistrias was succeeded as Governor by his younger brother, Augustinos Kapodistrias. Augustinos ruled only for six months, during which the country was very much plunged into chaos. Subsequently, King Otto was given the throne of the newly founded Kingdom of Greece.

Legacy and honours

[edit]Greece

[edit]Kapodistrias is greatly honoured in Greece today. In 1944 Nikos Kazantzakis wrote the play "Capodistria" in his honour. It is a tragedy in three acts and was performed at the Greek National Theatre in 1946 to celebrate the anniversary of 25 March.[65] The University of Athens is named "Kapodistrian" in his honour; the Greek euro coin of 20 cent bears his face and name,[66] as did the obverse of the 500 drachmas banknote of 1983–2001,[67] before the introduction of the euro, and a major administrative reform that reduced the number of municipalities in the late 1990s, named the Kapodistrias reform, also carries his name. The fears that Britain, France and Russia had of any liberal and Republican movement at the time, because of the Reign of Terror in the French Revolution, led them to insist on Greece becoming a monarchy after Kapodistrias' death. His summer home in Koukouritsa, Corfu has been converted to a museum commemorating his life and accomplishments and has been named Kapodistrias Museum in his honour.[68][69] It was donated by his late grand niece Maria Desylla-Kapodistria, to three cultural societies in Corfu specifically for the aforementioned purposes.[69] Society – Political Party of the Successors of Kapodistrias is a present-day political party in Greece.

Slovenia

[edit]On 8 December 2001 in the city Capodistria (Koper) of Slovenia a lifesize statue of Ioannis Kapodistrias was unveiled in the central square of the municipality.[20] The square was renamed after Kapodistrias,[70] since Koper was the place of Kapodistrias' ancestors before they moved to Corfu in the 14th century.[20][70] The statue was created by Greek sculptor K. Palaiologos and was transported to Koper by a Greek Naval vessel.[20] The ceremony was attended by the Greek ambassador and Eleni Koukou, a Kapodistrias scholar and professor at the National and Kapodistrian University of Athens.[20]

In the area of bilateral relations between Greece and Slovenia the Greek minister for Development Dimitris Sioufas met on 24 April 2007 with his counterpart Andrej Vizjak, Economy minister of Slovenia, and among other things he mentioned: "Greece has a special sentimental reason for these relations with Slovenia, because the family of Ioannis Kapodistrias, the first Governor of Greece, hails from Koper of Slovenia. And this is especially important for us."[71]

Switzerland

[edit]On 21 September 2009, the city of Lausanne in Switzerland inaugurated a bronze statue of Kapodistrias in Ouchy. The ceremony was attended by the Foreign Ministers of the Russian Federation, Sergei Lavrov and of Switzerland, Micheline Calmy-Rey.[72] In addition, the allée Ioannis-Capodistrias in Ouchy at Lausanne was named after him.[73]

The cantons of Geneva and Vaud in Switzerland awarded Kapodístrias honorary citizenship.[74]

The quai Capo d'Istria in the city of Geneva, Switzerland is named after Kapodistrias.[75]

Russia

[edit]

On 19 June 2015 Prime Minister of Greece Alexis Tsipras, in the first of that day's activities, addressed Russians of Greek descent at a statue of Ioannis Kapodistrias in St. Petersburg.[76][77][78]

International network

[edit]On 24 February 2007, the cities of Aegina, Nafplion, Corfu, Koper-Capodistria, and Famagusta (one of the notable families of Famagusta was the Gonemis family, from whom Ioannis Capodistrias mother, Adamantine Gonemis, was descended) created the Ioannis Kapodistrias Network, a network of municipalities which are associated with the late governor. The network aims to promote the life and vision of Ioannis Kapodistrias across borders. The presidency of the network is currently held by the Greek municipality of Nafplion.[79]

Notes

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Γεώργιος Δ. Δημακόπουλος: "Αι Κυβερνητικαί Αρχαί της Ελληνικής Πολιτείας (1827–1833)" (G.D.Dimakopoulos: Hellenic State government authorities (1827–1833))

- ^ a b c d e f g h "Kapodistrias, Ioannis Antonios, Count". Encyclopædia Britannica. 2008. Retrieved 28 January 2008. Komis born February 11, 1776, Corfu [Greece] died October 9, 1831, Návplion, Greece. Quote: Count Kapodístrias, Ioánnis Antónios, Italian Conte Giovanni Antonio Capo D'istria Greek statesman who was prominent in the Russian foreign service during the reign of Alexander I (reigned 1801–25) and in the Greek struggle for independence. The son of Count Antonio Capo d'Istria, he was born in Corfu (at that time under Venetian rule), studied at Padua, and then entered government service. In 1799 Russia and Turkey drove the French...

- ^ Helenē E. Koukkou (2000). Iōannēs Kapodistrias, Rōxandra Stourtza: mia anekplērōtē agapē : historikē viographia. Ekdoseis Patakē. p. 35. ISBN 9789603784791.

Στίς 10 Φεβρουαρίου τού 1776 τό ζεύγος Αντωνίου καί Διαμαντίνας Καποδίστρια έφερνε στόν κόσμο τό έκτο παιδί τους, μέσα στό άρχοντικό τους σπίτι, στόν παραλιακό δρόμο τού νησιού, κοντά στήν περίφημη πλατεία, τήν Σπιανάδα, πού ...

- ^ Dionysios A. Zakythēnos (1978). Metavyzantina kai nea Hellēnika. Zakythēnos. p. 500.

ΙΩΑΝΝΗΣ ΚΑΠΟΔΙΣΤΡΙΑΣ ΤΑ ΠΡΟΟΙΜΙΑ ΜΙΑΣ ΜΕΓΑΛΗΣ ΠΟΛΙΤΙΚΗΣ ΣΤΑΔΙΟΔΡΟΜΙΑΣ Συνεπληρώθησαν διακόσια έτη άπό της ... και της Διαμαντίνας, τό γένος Γολέμη ή Γονέμη, έγεννήθη έν Κερκύρα την 31 Ίανουαρίου/10 Φεβρουαρίου 1776.

- ^ Helenē E. Koukkou (1983). Historia tōn Heptanēsōn apo to 1797 mechri tēn Anglokratia. Ekdoseis Dēm.N. Papadēma. p. 94.

Ό Ιωάννης Καποδίστριας γεννήθηκε στήν Κέρκυρα, στίς 10 Φεβρουαρίου 1776, καί ήταν τό εκτο παιδί τοΰ Αντώνιου ...

- ^ Michael Newton (2014). Famous Assassinations in World History: An Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO. pp. 252–. ISBN 978-1-61069-286-1.

- ^ a b c International Society on the History of Medicine Archived 2017-12-16 at the Wayback Machine Paper: JOHN CAPODISTRIAS (1776–1831): THE EMINENT POLITICIAN-DOCTOR AND FIRST GOVERNOR OF GREECE ISHM 2006, 40th International Congress on the History of Medicine. Quote: "John Capodistrias (1776–1831) was a notable politician-doctor. The son of one of the most aristocratic family of Corfu, he was sent to Italy by his family and studied medicine at the University of Padua." and: Ioannis Kapodistrias was the leading Greek politician and one of the most eminent politicians and diplomats in Europe. He was born in Corfu in 1776. He was son of an aristocratic family whose ascendants had been distinguished in during the Venetian wars against Ottoman Turks, having obtained many administrative privileges (1) (1)=1. Koukkou E. (ELENI KOUKKOU) The Greek State (1830–1832). In: History of the Greek Nation. Ekdotiki Athinon 1975, Vol. XXII: 549–561.

- ^ William Philip Chapman (1993). Karystos: city-state and country town. Uptown Press. p. 163. Retrieved 3 August 2012.

Actually, Russia's distinguished diplomat and Foreign Minister, and later Greece's first president (1827–31)...

- ^ a b Helenē E. Koukkou (2001). Ioannis A. Kapodistrias: the European diplomat and statesman of the 19th century; Roxanda S. Stourdza : a famous woman of her time : a historical biography. Society for the Study of Greek History. p. 9. ISBN 9789608172067. Retrieved 3 August 2012.

Kapodistrias distinguished himself in the diplomatic and political arena when he was still a young man...But he too sensed that his Liberal and Republican ideals were too advanced for his time

- ^ Charles A. Frazee (1969). The Orthodox Church and Independent Greece, 1821–1852. CUP Archive. pp. 71–72. GGKEY:GTHG6TEJ1AX. Retrieved 3 August 2012.

...a distinguished career in political and diplomatic affairs...

- ^ Gerhard Robbers (2006). Encyclopedia of World Constitutions. Infobase Publishing. p. 351. ISBN 978-0-8160-6078-8. Retrieved 25 November 2012.

The foundations of the Greek state were built under the leadership of Ioannis Kapodistrias, a statesman of ...

- ^ Επίτομο λεξικό της Ελληνικής Ιστορίας Compound Dictionary of Greek History from the National and Kapodistrian University of Athens Website Quote: 1776 Γεννιέται στην Κέρκυρα ο Ιωάννης Καποδίστριας, γιος του Αντωνίου και της Αδαμαντίνης – το γένος Γονέμη – μία από τις μεγαλύτερες μορφές της Ευρώπης, διπλωμάτης και πολιτικός, πρώτος κυβερνήτης της Ελλάδας και θεμελιωτής του νεότερου Ελληνικού Κράτους. Έκδοση: Το Βήμα, 2004. Επιμέλεια: Βαγγέλης Δρακόπουλος – Γεωργία Ευθυμίου Translation: 1776 In Corfu is born Ioannis Kapodistrias, son of Antonios and Adamantini – nee Gonemi – one of the greatest personalities of Europe, diplomat and politician, first Governor of Greece and founder of the Modern Greek State. Publisher To Vima 2004.

- ^ Manos G. Birēs; Márō Kardamítsī-Adámī (2004). Neoclassical Architecture In Greece. Getty Publications. p. 17. ISBN 978-0-89236-775-7. Retrieved 5 December 2012.

Popular depictions of the leaders of the Greek struggle for independence: Ioannis Kapodistrias, founder of the modern Greek state, and Adamantios Korai's, herald of the Greek Enlightenment.

- ^ Council of Europe (1999). Report on the Situation of Urban Archaeology in Europe. Council of Europe. p. 117. ISBN 978-92-871-3671-8. Retrieved 5 December 2012.

The first legislative enactments dealing with Museums and the preservation of archaeological finds date from the formation of the modern Greek state (1828) and originated with the Governor of Greece, Ioannis Kapodistrias, who issued Order no. 2400/12.5.1828 "To the acting Commissaries in the Aegean Sea", and the Founding Law of 21.10.1829

- ^ a b c d Woodhouse, Christopher Montague (1973). Capodistria: the founder of Greek independence. Oxford University Press. pp. 4–5. OCLC 469359507.

The family of Gonemis or Golemis, which originated in Cyprus, had moved to Crete when Cyprus fell in the 16th century; then to Epirus when Crete fell in the 17th, settling near Argyrokastro in modern Albania; and finally to Corfu.

- ^ Pournara, E. (2003). Eikonographēmeno enkyklopaidiko lexiko & plēres lexiko tēs neas Hellēnikēs glōssas. Athēna: Ekdotikos Organismos Papyros. (Illustrated Encyclopaedic Dictionary and Full Dictionary of Modern Greek Papyros, Larousse Publishers) Quote (Translation): Ioannis Kapodistrias 1776 Corfu. Diplomat and politician. Scion of distinguished Corfiote Family p. 785 2003 Edition ISBN 960-8322-06-5

- ^ a b Kurt Fassmann; Max Bill (1976). Die Grossen der Weltgeschichte: Goethe bis Lincoln. Kindler. p. 358. Retrieved 24 November 2012.

Februar 1776 als Sohn des Arztes und Politikers Graf Antonio Maria Kapodistrias und seiner Frau, einer Grafin Gonemi, in Korfu geboren. Er begann 1744 in Padua ein Medizinstudium und wurde Arzt und Politiker wie sein Vater, zunächst ...

- ^ Ioannis Kapodistrias Archived 2008-09-30 at the Wayback Machine San Simera Retrieved 26-07-08

- ^ C. W. Crawley, "John Capodistrias and the Greeks before 1821" Cambridge Historical Journal, Vol. 13, No. 2 (1957), pp. 162–182: Quote: "John Capodistrias does not wholly fit into this picture. His ancestors' family, coming from Istria to Corfu in the fourteenth century...."

- ^ a b c d e Slovenia Honours Kapodistria (in Greek) Archived 2017-10-06 at the Wayback Machine From the National and Kapodistrian University of Athens website: "Η Σλοβενία τιμά τον Καποδίστρια Tα αποκαλυπτήρια ανδριάντα, ύψους 1.76μ., του Ιωάννη Καποδίστρια έγιναν στις 8 Δεκεμβρίου 2001 στην κεντρική πλατεία της πόλης Capo d'Istria της Σλοβενίας. Η ελληνική κυβέρνηση εκπροσωπήθηκε από τον Πρέσβη κ. Χαράλαμπο Χριστόπουλο, ενώ την τελετή παρακολούθησε η καθηγήτρια του Πανεπιστημίου μας κ. Ελένη Κούκου, η οποία με σχετικές εργασίες της έχει φωτίσει άγνωστες πτυχές της ζωής του μεγάλου πολιτικού, αλλά και του ευαίσθητου ανθρώπου Καποδίστρια. Με την ανέγερση του ανδριάντα και με την αντίστοιχη μετονομασία της πλατείας, η γη των προγόνων του πρώτου Κυβερνήτη της σύγχρονης Ελλάδας θέλησε να τιμήσει τη μνήμη του. Το έργο είναι από χαλκό και το φιλοτέχνησε ο γνωστός γλύπτης Κ. Παλαιολόγος. Η μεταφορά του στο λιμάνι της πόλης Κόμμες, όπως σήμερα ονομάζεται το Capo d'Istria, έγινε με πλοίο του Eλληνικού Πολεμικού Ναυτικού." ("The unveiling of the statue of Ioannis Kapodistrias of height 1.76 m took place on 8 December 2001 in the central square of the city Capo d'Istria of Slovenia. The Greek government was represented by ambassador Charalambos Christopoulos, while the ceremony was observed by the professor of our university Mrs. Eleni Koukou, who through her relevant works has shed light on unknown areas of the life of the great politician but also the sensitive man, Kapodistrias. With the raising of the statue and the renaming of the square, the land of the ancestors of the first governor of Modern Greece wished to honour his memory. The statue is made of bronze and was created by famous sculptor K. Palaiologos. Its transportation to the port of the city Kommes, as is the present name of Capo d'Istria, was carried out by a ship of the Greek Navy."

- ^ a b circom-regional Archived 2008-06-27 at the Wayback Machine Quote: "The international port of Koper, the capital of Istria during Venetian rule in the 15th and 16th centuries, is situated on the Adriatic coast. Koper, then called Capo d' Istria, is linked with Greece. Ioannis Kapodistrias, the first Greek governor, came from here. In fact, his surname comes from the name of the city: Capo d' Istria. The initial name of the governor's ancestors was Vittori. In the 14th century, they immigrated from Capo d'Istria, discarded their surname and catholic dogma, converted into the orthodox dogma and were soon completely Hellenized." retrieved 21-06-2008

- ^ a b EFTHYMIOS TSILIOPOULOS, "This week in history. Changing the capital" Archived 2012-03-21 at the Wayback Machine, Athens News, 17 August 2007, page: A19. Article code: C13248A191, retrieved 21-06-2008. Quote: "Kapodistrias was born on Kerkyra (Corfu) in 1776, the second child of Count Antonios Maria Kapodistrias. His mother, Adamantia Genome, hailed from Epirus. Originally, the Kapodistrias family was from the Adriatic city of Capo d'Istria (a port of a small island near Trieste), and its original name was Vitori. Centuries before the birth of Ioannis the family had moved to Kerkyra, where it embraced Orthodoxy and changed its name to that of its town of origin."

- ^ [Γενεολογικό δέντρο Καποδίστρια, Κέρκυρα, Ιόνιον Φως, Δ.Ταλιάνης]

- ^ a b Crawley C. W. (1957). "John Capodistrias and the Greeks before 1821". Cambridge Historical Journal. 13 (2). Cambridge University Press: 166. OCLC 478492658.

...Capodistrias...his mother, Adamantine Gonemes, who came of a substantial Greek family in Epirus

- ^ Center for Neo-Hellenic Studies (1970). Neo-Hellenika, Volumes 1–2. A. M. Hakkert. p. 73. OCLC 508157775.

A predecessor of Soderini in the office of Venetian consul in Cyprus was "Sir Alessandro Goneme", who according to Pietro Della Valle, who met him at the Salines (Larnaca Scala) on 4 September 1625, was "not of their [the Venetians'] nobles but a man of that class of honorable citizens, which often supplies the Republic with secretaries." This may have been reflecting the fact that the Gonemes – a Greek family...

- ^ Alberto Torsello, Letizia Caselli (2005). Ville venete: La provincia di Venezia. Marsilio. p. 113. ISBN 9788831787222.

...Gonemi, greci agiati venuti da Cipro...

- ^ Helenē E. Koukkou (1983). Historia tōn Heptanēsōn apo to 1797 mechri tēn Anglokratia. Ekdoseis Dēm.N. Papadēma. Retrieved 24 May 2012.

Ό Ιωάννης Καποδίστριας γεννήθηκε στήν Κέρκυρα, στίς 10 Φεβρουαρίου 1776, καί ήταν τό εκτο παιδί τοΰ Αντώνιου Καποδίστρια καί τής Διαμαντίνας, τό γένος Γονέμη. Καί οί δύο έκεί- νες οικογένειες ήταν γραμμένες στή χρυσή βίβλο τοΰ νησιοΰ

- ^ Heidelberger Jahrbücher der Literatur. J.C.B. Mohr. 1864. p. 66. Retrieved 24 May 2012.

- ^ ΤΟ ΠΑΡΟΝ Newspaper ΑΚΑΔΗΜΙΑ ΑΘΗΝΩΝ ΚΡΙΤΙΚΕΣ ΠΑΡΑΤΗΡΗΣΕΙΣ ΣΤΟ ΒΙΒΛΙΟ ΙΣΤΟΡΙΑΣ ΤΗΣ ΕΚΤΗΣ ΔΗΜΟΤΙΚΟΥ ("Academy of Athens Critical Observations about the 6th-Grade History Textbook"): "3.2.7. Σελ. 40: Δεν αναφέρεται ότι ο Καποδίστριας ήταν Κερκυραίος ευγενής." ("3.2.7. Σελ. 40 p. 40. It is not mentioned that Kapodistrias was a Corfiote Nobleman.") "...δύο ιστορικούς της Aκαδημίας κ.κ. Mιχαήλ Σακελλαρίου και Kωνσταντίνο Σβολόπουλο" ("Prepared by the two Academy Historians Michael Sakellariou and Konstantinos Svolopoulos 18 March 2007")

- ^ To Vima online New Seasons (Translation) Article by Marios Ploritis (ΜΑΡΙΟΣ ΠΛΩΡΙΤΗΣ) : Δύο μεγάλοι εκσυγχρονιστές Παράλληλοι βίοι Καποδίστρια και Τρικούπη: "Two great modernizers : Parallel lives Kapodistrias and Trikoupis" Quote: Ηταν, κι οι δυο, γόνοι ονομαστών οικογενειών. Κερκυραίος και "κόντες" ο Καποδίστριας, που οι πρόγονοί του είχαν πολεμήσει μαζί με τους Βενετούς, κατά των Τούρκων. Translation: They were both scions of famous families. Corfiote and Count was Kapodistrias whose ancestors fought with the Venetians against the Turks.

- ^ Rand Carter, "Karl Friedrich Schinkel's Project for a Royal Palace on the Acropolis", The Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians, Vol. 38, No. 1 (Mar. 1979), pp. 34–46: Quote: "Count John Capodistrias (his ancestors on Corfu had received a patent of nobility from the Venetian Republic)..."

- ^ The Columbia Encyclopedia, 6th ed., © 2004, Columbia University Press. Licensed from Lernout & Hauspie Speech Products N.V. All rights reserved. Archived 2008-10-02 at the Wayback Machine Quote: CAPO D'ISTRIA, GIOVANNI ANTONIO, COUNT kä'pō dē'strēä, Gr. Joannes Antonios Capodistrias or Kapodistrias, 1776–1831, Greek and Russian statesman, b. Corfu. See study by C. M. Woodhouse (1973).

- ^ "Ioánnis Antónios Kapodístrias," Microsoft Encarta Online Encyclopedia, 2007 Archived 2009-11-01 at the Wayback Machine © 1997–2007 Microsoft Corporation. All Rights Reserved. Archived 2009-04-11 at the Wayback Machine Quote: Ioánnis Antónios Kapodístrias (1776–1831), Greek-Russian statesman and provisional president of Greece. A native of Corfu (Kérkira), Greece, Kapodístrias was secretary of state in the Russian-controlled republic of the Ionian Islands from 1803 to 1809, when he entered the Russian diplomatic service. He soon became one of the chief advisers of Tsar Alexander I, and from 1816 to 1822 shared the conduct of Russian foreign affairs with Count Karl Robert Nesselrode. In the 1820s he became active in the movement for Greek independence from the Ottoman Empire. Elected head of the rebel Greek government in 1827, he was assassinated by political rivals in 1831. In early life he was known by the Italian name Capo d'Istria..

- ^ JSTOR Cambridge University Press Book Review: Capodistria: The Founder of Greek Independence by C. M. Woodhouse London O.U.P. 1973 ISBN 0-19-211196-5 ISBN 978-0192111968 Author(s) of Review: Agatha Ramm The English Historical Review, Vol. 89, No. 351 (Apr., 1974), pp. 397–400 This article consists of 4 page(s). Quote: Capodistrias was born in Corfu in 1776 into the aristocracy of a subjected people...

- ^ Ghervas, Stella (2016). "A 'goodwill ambassador' in the post-Napoleonic era: Roxandra Edling-Sturdza on the European scene". In Sluga, Glenda; James, Carolyn (eds.). Women, Diplomacy and International Politics since 1500. Routledge. pp. 160, 164. ISBN 978-0-415-71465-5.

- ^ a b c d e f g The Journal of Modern History Capodistrias and a "New Order" for Restoration Europe: The "Liberal Ideas" of a Russian Foreign Minister, 1814–1822 Patricia Kennedy Grimsted Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study The Journal of Modern History, Vol. 40, No. 2 (Jun., 1968), pp. 166–192 Quote: (Metternich's comments): Kapodistrias is not a bad man, but honestly speaking he is a complete and thorough fool, a perfect miracle of wrong-headedness...He lives in a world to which our minds are often transported by a bad nightmare. and Such in 1819 was Metternich's estimate of John Capodistrias, the young Greek patriot who served Alexander I as Russian foreign secretary. Capodistrias' world was a nightmare for the Austrian chancellor because it held the possibilities of reform in domestic and international order and suggested a degree of Russian influence which clearly threatened Metternich's aims for Austrian domination in European politics. If Metternich were to succeed he realised the importance of undermining Capodistrias' position as the only man of real influence in the Russian cabinet who presented a progressive alternative to his own system. When Metternich spoke of the struggle as "the conflict between a positive and a negative force," he recognised Capodistrias' world as antithetical to his own. Metternich, of course, won the immediate struggle; Capodistrias left the Russian foreign office in 1822. Yet time vindicated Capodistrias' sense of a new European... also: The stage was well set for his transfer to Russia when the French overran his native Corfu in 1807. Capodistrias entered the Russian service in 1809; ...

- ^ Gründervater der modernen Schweiz – Ignaz Paul Vital Troxler Archived 2014-05-29 at the Wayback Machine Quote: Die Annahme des Bundesvertragsentwurfs durch die Kantone suchte eine Note Kapodistrias günstig zu beeinflussen. Sie stellte in Aussicht, der Wiener Kongress werde in einem Zusatzartikel zum ersten Pariser Frieden (vom 30. Mai 1814) die Unabhängigkeit und Verfassung der Schweiz garantieren und einen schweizerischen Gesandten am Kongress zulassen, falls dieser den neuen Bundesvertrag mit sich bringe. and Trotz der wiederholten Versicherung des Selbstkonstituierungsrechtes der Schweiz wollten auch die Diplomaten der europäischen Grossmächte ein Wort zur künftigen Verfassung mitreden. "Wir haben vor", schrieb der russische Geschäftsträger Johannes Kapodistrias (1775–1831; in Schweizer Geschichtsbüchern oftmals nach seinem Heimatort als Capo d'Istria tituliert), "die Kantone nicht sich selbst zu überlassen. Ihre in Zürich versammelten Deputierten bieten uns die erste Handhabe dar. Wir versuchen ihnen die Verhaltungslinien vorzuschreiben. Wir zeigen den Patriziern, dass die Rückkehr zur alten reinen Aristokratie absurd und unzulässig wäre. Wir lassen umgekehrt die Demokraten fühlen, dass der Geist der französischen Legislation für immer aus den schweizerischen Verfassungen verschwinden müsse."

- ^ a b c d Brewer 2011, p. 57.

- ^ Brewer 2011, pp. 31–32.

- ^ a b Brewer 2011, p. 32.

- ^ Brewer 2011, p. 34.

- ^ Brewer 2011, p. 49.

- ^ Phillips, Walter Alison (1911). . In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 5 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 285–286. "CAPO D'ISTRIA, GIOVANNI ANTONIO [Joannes], Count (1776–1831), Russian statesman and president of the Greek republic, was born at Corfu on the 11th of February 1776. He belonged to an ancient Corfiot family which had immigrated from Istria in 1373, the title of count being granted to it by Charles Emmanuel, duke of Savoy, in 1689".

- ^ Brewer 2011, p. 105.

- ^ a b Brewer 2011, pp. 100–107.

- ^ Brewer 2011, p. 107.

- ^ Ioannis Capodistrias, guardian angel of independence of the Vaud, Capodistrias-Spinelli-Europe, 27 September 2009

- ^ a b c d Brewer 2011, p. 302.

- ^ Notes on Kapodistrias Quote: Την 7 Ιανουαρίου 1828 έφθασεν ο Καποδίστριας εις Ναύπλιον και την 8 έφθασεν εις Αίγινα, και εβγήκεν μετά μεγάλης υποδοχής, και αφού έδωκεν τον όρκον, άρχισε τας εργασίας. Translation: On 7 January 1828 Kapodistrias arrived in Nafplion and on the 8th in Aegina

- ^ Brewer 2011, p. 337.

- ^ Brewer 2011, pp. 337–338.

- ^ a b c d e f Brewer 2011, p. 338.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Brewer 2011, p. 343.

- ^ a b Brewer 2011, p. 339.

- ^ Brewer 2011, pp. 338–339.

- ^ a b c Brewer 2011, p. 344.

- ^ Brewer 2011, pp. 339–340.

- ^ a b Brewer 2011, p. 340.

- ^ a b Elaine Thomopoulos (2011). The History of Greece. ABC-CLIO. p. 71. ISBN 978-0-313-37511-8.

- ^ John S. Koliopoulos, Brigands with a Cause – Brigandage and Irredentism in Modern Greece 1821–1912, Clarendon Press Oxford (1987), p. 67.

- ^ Fermor, Patrick Leigh, "Mani: Travels in the Southern Peloponnese," at 57–65 (NYRB, 2006)(ISBN 9781590171882).

- ^ Id.

- ^ a b c d e f Brewer 2011, p. 348.

- ^ Brewer 2011, p. 349.

- ^ Vassilis Lambropoulos, "C. P. Cavafy, The Tragedy of Greek Politics: Nikos Kazantzakis' play 'Capodistria'" Archived 2008-02-29 at the Wayback Machine. Quote: Ioannis Capodistria (1776–1831) was a Greek from Corfu who had a distinguished diplomatic career in Russia, reaching the rank of Foreign Minister under Czar Alexander I.

- ^ European Central Bank – Eurosystem – Coins, Greece,

- ^ Bank of Greece Archived 2009-03-28 at the Wayback Machine. Drachma Banknotes & Coins: 500 drachmas Archived 2007-10-05 at the Wayback Machine. – Retrieved on 27 March 2009.

- ^ Helene E. Koukkou, John Capodistrias: The Man – The Fighter,National and Kapodistrian University of Athens, Capodistrias and Education, 1803–1822. Helene E. Koukkou, Volume I, The Vienna Society of the Friends of the Muses. Quote: ...and the Capodistrias Papers on Corfu, Capodistrias' native island.

- ^ a b Eleni Bistika Archived 2017-10-07 at the Wayback Machine Kathimerini Article on Ioannis Kapodistrias 22-02-2008 Quote: Η γενέτειρά του Κέρκυρα, ψύχραιμη, απολαμβάνει το προνόμιο να έχει το γοητευτικό Μουσείο Καποδίστρια στη θέση Κουκουρίσα, Translation: His birthplace, Corfu, cool, enjoys the privilege to have the charming Museum Kapodistria in the location Koukourisa and εξοχική κατοικία με τον μαγευτικό κήπο της οικογενείας Καποδίστρια, που η Μαρία Δεσύλλα – Καποδίστρια δώρισε στις τρεις κερκυραϊκές εταιρείες Translation: summer residence with the enchanting garden of the Kapodistrias family, which Maria Dessyla Kapodistria donated to the three Corfiote societies

- ^ a b John Capodistrias and the Greeks before 1821 C. W. Crawley Cambridge Historical Journal, Vol. 13, No. 2 (1957), pp. 162–182: "John Capodistrias does not wholly fit into this picture. His ancestors' family, coming from Istria to Corfu in the fourteenth century...."

- ^ "Greek Ministry of Development". Archived from the original on 2007-05-11. Retrieved 2008-06-21.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) Announcement (In Greek) Quote: "Η Ελλάδα έχει κι έναν ιδιαίτερο συναισθηματικό λόγο για αυτές τις σχέσεις μαζί με τη Σλοβενία, γιατί η οικογένεια του πρώτου κυβερνήτη της Ελλάδας, του Ιωάννη Καποδίστρια, κατάγεται από την πόλη Κόπερ της Σλοβενίας. Και αυτό είναι ιδιαίτερα σημαντικό για μας." Retrieved 21-06-2008 - ^ "Ioannis Kapodistrias bust unveiled". World Council of Hellenes Abroad. 23 September 2009. Archived from the original on 27 July 2011. Retrieved 9 October 2009.

- ^ Lausanne inaugure une allée en honneur du Grec Ioannis Kapodistrias

- ^ Ioannis Kapodistrias - Official Swiss government site

- ^ Quai Capo d'Istria

- ^ "Kremlin: Russian loan not discussed in Tsipras-Putin talks". Associated Press. 19 June 2015.

- ^ "Greek Prime Minister Alexis Tsipras (C) speaks with Greek expatriates in front of the statue of the founder of modern Greek state Ioannis Kapodistrias in St. Petersburg, Russia, June 19, 2015. REUTERS/Maxim Shemetov". Reuters.

- ^ "ECB boosts emergency funding as Greek banks bleed, Tsipras calm". Reuters. 21 June 2015.

- ^ "Την προεδρία του Ναυπλίου στο "Δίκτυο πόλεων Ιωάννης Καποδίστριας" εξασφάλισε ο Δήμαρχος Ναυπλιέων Δημήτρης Κωστούρος". Municipality of Nafplio. Retrieved 13 June 2016.

Further reading

[edit]- Brewer, David (2011). The Greek War of Independence : the struggle for freedom from Ottoman oppression. New York: Overlook. ISBN 978-1-59020-691-1. OCLC 706018492.

- Stella Ghervas, "Le philhellénisme russe : union d'amour ou d'intérêt?", in Regards sur le philhellénisme, Geneva, Permanent Mission of Greece to the United Nations (Mission permanente de la Grèce auprès de l'ONU), 2008.

- Stella Ghervas, Réinventer la tradition. Alexandre Stourdza et l'Europe de la Sainte-Alliance, Paris, Honoré Champion, 2008. ISBN 978-2-7453-1669-1

- Stella Ghervas, "Spas' political virtues : Capodistria at Ems (1826)", Analecta Histórico Médica, IV, 2006 (with A. Franceschetti).

- Mathieu Grenet, La fabrique communautaire. Les Grecs à Venise, Livourne et Marseille, 1770–1840, Athens and Rome, École française d'Athènes and École française de Rome, 2016 (ISBN 978-2-7283-1210-8)

- Michalopoulos, Dimitris, America, Russia and the Birth of Modern Greece, Washington-London: Academica Press, 2020, ISBN 978-1-68053-942-4.

External links

[edit] Media related to Ioannis Kapodistrias at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Ioannis Kapodistrias at Wikimedia Commons Quotations related to Ioannis Kapodistrias at Wikiquote

Quotations related to Ioannis Kapodistrias at Wikiquote

- Ioannis Kapodistrias

- 1776 births

- 1831 deaths

- 18th-century Greek people

- 19th-century heads of state of Greece

- 19th-century prime ministers of Greece

- 19th-century Greek physicians

- Politicians from Corfu

- Greek people of Cypriot descent

- Greek people of Italian descent

- Greek nobility

- 19th-century Italian nobility

- Eastern Orthodox Christians from Greece

- Assassinated Greek politicians

- Deaths by firearm in Greece

- Foreign ministers of the Russian Empire

- Russo-Turkish War (1828–29)

- Politicians from the Russian Empire

- People murdered in Greece

- Greek independence activists

- Septinsular Republic

- 1831 murders in Europe

- Kapodistrias family

- 19th-century Greek scientists

- Participants to the Congress of Vienna

- Assassinated heads of state in Europe

- Politicians assassinated in the 1830s

- Greek Freemasons