Jet (magazine)

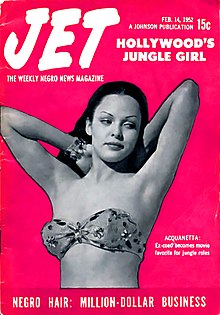

February 14, 1952, cover with Acquanetta | |

| Former editors | Mitzi Miller, Mira Lowe, Sylvia P. Flanagan, Robert E. Johnson |

|---|---|

| Categories | News magazine |

| Frequency | online, formerly a print weekly |

| Publisher | Ebony Media Operations, LLC (2016–present) Johnson Publishing Company (1951–2016) |

| Total circulation (June, 2014) | (June 2012) 1.1 million 720,000[1] |

| Founder | John H. Johnson |

| First issue | November 1, 1951 |

| Final issue | June 2014 (print) continuing in digital (2014) |

| Country | United States |

| Based in | Los Angeles, California, U.S.[2] |

| Language | English |

| Website | jetmag |

| ISSN | 0021-5996 |

| OCLC | 1781708 |

After noting the under-representation of African Americans in the media, publisher John H. Johnson had created Jet magazine to offer Black Americans proper representation.[3] Jet is an American weekly digital magazine focusing on news, culture, and entertainment related to the African-American community. Founded by Johnson in November 1951 of the Johnson Publishing Company in Chicago, Illinois,[4][5] the magazine was billed as "The Weekly Negro News Magazine". Jet chronicled the civil rights movement from its earliest years, including the murder of Emmett Till, the Montgomery bus boycott, and the activities of civil rights leader Martin Luther King Jr.

Jet was printed from November 1, 1951, in digest-sized format in all or mostly black-and-white until its December 27, 1999, issue. In 2009, Jet expanded one of the weekly issues to a double issue published once each month. Johnson Publishing Company struggled with the same loss of circulation and advertising as other magazines and newspapers in the digital age, and the final print issue of Jet was published on June 23, 2014, continuing solely as a digital magazine app.[6][1] In 2016, Johnson Publishing sold Jet and its sister publication Ebony to private equity firm Clear View Group. As of the date of sale, the publishing company is known as Ebony Media Corporation.[7]

History

[edit]Early history

[edit]The first issue of Jet was published on November 1, 1951, by John H. Johnson in Chicago, Illinois.[8] Johnson called his magazine Jet because he wanted the name to symbolize "Black and speed". In Jet's first issue, Johnson wrote, "In the world today everything is moving along at a faster clip. There is more news and far less time to read it."[8][9] Jet's goal was to provide "news coverage on happenings among Negroes all over the U.S.—in entertainment, politics, sports, social events as well as features on unusual personalities, places and events."[9] Redd Foxx called the magazine "the Negro bible".[10]

1952–2014

[edit]Jet was published as a sister zine to the Ebony magazine which Johnson published 6 years earlier in 1945.[11] Jet became nationally known in 1955 for its shocking and graphic coverage of the murder of Emmett Till. Its popularity was enhanced by its continuing coverage of the burgeoning civil rights movement.[10] The publication of Till's brutalized corpse within the September 22, 1955[12] issue inspired the black community to address racial violence, catalyzing the civil rights movement. Some of the popular models of Jet during this era included Vera Francis and Nancy Westbrook.[13] The Johnson Publishing Company's campaign for economic, political and social justice influenced its inclusion of progressive views.[14] From 1970 to 1975, Jet challenged conservative readers' anti-abortion stance by giving physicians who performed abortions a platform to discuss scientific facts about abortion procedures.[15]

2014–present

[edit]In May 2014, the publication announced the print edition would be discontinued and switch to a digital format in June.[16]

Changes in ownership

[edit]In June 2016, after 71 years, Jet and its sister publication Ebony were sold by Johnson Publishing to Clear View Group, an Austin, Texas-based private equity firm, for an undisclosed amount but the sale did not include the photo archives.[17] In July 2019, three months after Johnson Publishing filed for Chapter 7 Bankruptcy liquidation, it sold its historic Jet and Ebony photo archives to a consortium of foundations to be made available to the public.[18][19]

In 2020, Ulysses “Junior” Bridgeman, a former NBA basketball player, became the new owner of Ebony Media's assets for $14 million in a bid out of a Houston bankruptcy court. Bridgeman placed a bid of $14 million to take ownership of the company. His sports and media group has hired Michele Ghee as Jet and Ebony magazine's new CEO.[20]

Content

[edit]Jet coverage includes: fashion and beauty tips, entertainment news, dating advice, political coverage, health tips, and diet guides, in addition to covering events such as fashion shows. The cover photo usually corresponds to the focus of the main story. Cover stories might be a celebrity's wedding, Mother's Day, or a recognition of the achievements of a notable African American.

Photography

[edit]One of the things that made Jet effective in its deliverance of messages in politics and entertainment was its uncensored method of vivid photography.[21] Jet took photos of Martin Luther King Jr. Speaking and greeting fans, as well as detailed pictures of the subjects of the Entertainment section, including of Jimi Hendrix. The most famous picture taken and published by Jet was the remains of Emmett Till's face after his tragic death in 1955.[22] Showing the picture uncensored and vividly describing what happened played a part in waking up the united states about its severe problem of racism[21]

Civil Movements

[edit]Similar to Essence, Jet routinely deplores racism in mainstream media, especially its negative depictions of black men and women. However, Hazell and Clarke report that between 2003 and 2004, Jet and Essence themselves ran advertising that was pervaded with racism and white supremacy.[23] Jet has published colorist advertisements in the past. An advertisement for Nadinola, a bleaching cream, appeared in an issue published in 1955. It depicts a light-skinned woman as the center of men's attention.[24] Amongst the Civil Rights movement of the 1950s, the Black is Beautiful Movement was also heavily covered within the 1960s through the glamorization of African women within multiple issues.[3]

Beauty

[edit]Publication

[edit]Jet claims to give young female adults confidence and strength because the women featured therein are strong and successful without the help of a man. Since 1952, Jet has had a full-page feature called "Beauty of the Week". This feature includes a photograph of an African American woman in a swimsuit (either one-piece or two-piece, but never nude), along with her name, place of residence, profession, hobbies, and interests. Many of the women are not professional models and submit their photographs for the magazine's consideration.[25] In 2024, The New Yorker wrote that Jet's "Beauties of the Week" column "democratized the thirst trap."[26]

Representation

[edit]During the time period when these issues were first being published, 'beauty' had a very Western-centric image. Jet however, provided African American women with a platform to boast their own image of self-confidence and illustrate better representation of African Americans in the media. An issue posted through Xavier University writes "The Eurocentric standard of beauty only tolerates straight hair, especially on Black women who have a natural kinky hair texture".[3] While within the course of the 50's there were societal confines of lighter skinned models with straight hair, there are notable early issues of Jet that spotlight African women with changeless hair, paving the way for Jet to have its reputation of rebellion and boldness that it does today.[3]

Entertainment

[edit]Media Coverage

[edit]Jet's coverage of entertainment spans throughout many topics of content, such as film, television, and music. Their coverage of music can be traced back as early as August 17, 1967, through their weekly list known as 'Soul Brothers Top 20'.[27] This survey consisted of Jet asking its readers to list their twenty personal favorite records, while also highlighting the artist's name and record label. This survey of listing top 20 artists and records would appear as a continuing trend in the magazine throughout the following decades. Implementing this survey initially into the issues allowed for notable artists spanning multiple years to be recognized amongst the publications, such as Aretha Franklin, Stevie Wonder, and Prince.[28] Jet's articles that fixate on these celebrities focalize on their cultural significance in society. One issue published on March 4, 1965 is encompassed entirely by the death and legacy of Nat King Cole. The publication delves heavily into his funeral ceremony, and how hundreds of people (including President Lyndon Johnson), had went to pay their respects.[29]

Census

[edit]In many issues of Jet there is a section of content titled census. This provides the reader with insight into the fluctuating number of people within the population that the magazine caters to. Congress representatives, artists, and other figures who pass away are all illustrated under this section, as well as their reputations and contributions to society.[30]

Notable people

[edit]- Robert C. Farrell (born 1936), journalist and member of the Los Angeles City Council, 1974–91, Jet correspondent

- Robert E. Johnson (born August 13, 1922, in Montgomery, Alabama; died January, 1996, in Chicago) was associate publisher and executive editor of Jet. He joined the Jet staff in February 1953, two years after it was founded by publisher John H. Johnson. He was one of the longest serving editors of Jet.

Awards and recognition

[edit]- Jet was rated No. 1 as the acme in news digesting for the Baltimore Afro-American newspaper on November 17, 1951.[31]

References

[edit]- ^ a b "Jet to stop printing weekly, change to digital app". The Washington Post. AP. May 7, 2014. Archived from the original on May 16, 2014.

- ^ Robert Channick (May 5, 2017). "Ebony cuts a third of its staff, moving editorial operations to LA". Chicagotribune.com. Retrieved June 8, 2019.

- ^ a b c d Shepherd, Jazmyn (January 1, 2019). "Jet Magazine: Celebrating Black Female Beauty". XULAneXUS. 16 (2).

- ^ "From Negro Digest to Ebony, Jet and EM". Ebony. Johnson Publishing Company. November 1992. pp. 50–55.

- ^ Almanac. (2006, 12). American History, 41, 11–13.

- ^ "Jet Magazine – Final Print Edition". Ebony Jet Shop. June 23, 2014. Archived from the original on August 18, 2016. Retrieved November 29, 2016.

- ^ "Ebony Jet Sold!". The Chicago Defender. June 16, 2016. Archived from the original on June 17, 2016. Retrieved November 29, 2016.

- ^ a b "From Negro Digest to Ebony, Jet and EM". Ebony. Johnson Publishing Company. November 1992. pp. 50–55.

- ^ a b "Jet". Jet. Johnson Publishing Company: 67. November 1, 1951. ISSN 0021-5996. Retrieved January 7, 2013.

- ^ a b Paul Finkelman (February 12, 2009). Encyclopedia of African American History. Oxford University Press. p. 25. ISBN 978-0-19-516779-5. Retrieved January 7, 2013.

- ^ "Ebony & Jet magazines' archive will (hopefully) soon be widely accessible". www.digitalmeetsculture.net. Retrieved November 13, 2024.

- ^ Jet. Johnson Publishing Company. September 22, 1955.

- ^ Clemens, Samuel. "Pageantry", Lulu Press. August 2022

- ^ Patton, June O. (September 22, 2005). "Remembering John H. Johnson, 1918–2005". Journal of African American History. 90 (4): 456–457. doi:10.1086/JAAHv90n4p456. S2CID 141214280. Retrieved December 1, 2019 – via Gale Academic OneFile.

- ^ Lumsden, Linda (October 2009). ""Women's Lib Has No Soul"?: Analysis of Women's Movement Coverage in Black Periodicals, 1968–73". Journalism History. 35 (3): 118–130. doi:10.1080/00947679.2009.12062794. S2CID 197649396.

- ^ "Jet magazine ending print edition, moving to digital only". CNN. May 7, 2014. Retrieved March 12, 2017.

- ^ Channick, Robert. "Johnson Publishing sells Ebony, Jet magazines to Texas firm". chicagotribune.com. Retrieved March 12, 2017.

- ^ "Rare look inside the Ebony and Jet magazine photo archive that just sold for $30M". CBS News. July 26, 2019. Retrieved July 27, 2019.

- ^ Noyes, Chandra (July 29, 2019). "Foundations Unite to Save Ebony Magazine Archives". artandobject.com. Journalistic, Inc. Retrieved August 3, 2019.

- ^ "Michele Ghee Named CEO of Ebony and Jet Magazine". Black Enterprise. January 19, 2021. Retrieved April 2, 2022.

- ^ a b Magazine, Smithsonian; Kuta, Sarah. "'Ebony' and 'Jet' Magazines' Iconic Photos Captured Black Life in America". Smithsonian Magazine. Retrieved November 13, 2024.

- ^ "Jet Magazine". Emmett Till Project. Retrieved November 13, 2024.

- ^ Hazell, Vanessa; Clarke, Juanne (2008). "Race and Gender in the Media: A Content Analysis of Advertisements in Two Mainstream Black Magazines". Journal of Black Studies. 39 (1): 5–21. doi:10.1177/0021934706291402. JSTOR 40282545. S2CID 144876832.

- ^ Shepard, Jazmyn (2019). "Jet Magazine: Celebrating Black Female Beauty". XULAneXUS. 16 (2).

- ^ "Reflections Of Black Beauty: How I Viewed Every Last One Of JET Magazine's Beauty Of The Week + Valentine's Day Jam Of The Day". Lavish Rebellion [DOT COM]. February 14, 2015. Retrieved October 29, 2024.

- ^ Wilson, Jennifer. "The Unfiltered Charm of Jet's Beauties of the Week". The New Yorker. Retrieved June 25, 2024.

- ^ "Jet Magazine "Soul Brothers Top 20" August 17, 1967". 45 Cat. October 31, 2024. Retrieved October 31, 2024.

- ^ Jet. Johnson Publishing Company. February 4, 1985.

- ^ Jet. Johnson Publishing Company. March 4, 1965.

- ^ Jet. Johnson Publishing Company. January 24, 2005.

- ^ "Baltimore Afro-American", Encyclopedia of African American Society, SAGE Publications, Inc., 2005, doi:10.4135/9781412952507.n57, ISBN 978-0-7619-2764-8

External links

[edit]- Jet, 1951-2008 issues (Google Books)

- Black History Seen Through Magazines

- John H. Johnson Archived September 3, 2017, at the Wayback Machine

- 1951 establishments in the United States

- 2014 establishments in the United States

- African-American magazines

- Lifestyle magazines published in the United States

- Online magazines published in the United States

- Weekly magazines published in the United States

- Defunct magazines published in the United States

- Digests

- Johnson Publishing Company

- Magazines established in 1951

- Magazines disestablished in 2014

- Magazines published in Chicago

- Online magazines with defunct print editions