Jesús Elizalde Sainz de Robles

Jesús Elizalde Sainz de Robles | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | Jesús Elizalde Sainz de Robles 1907 Viana, Spain |

| Died | 1980 Vejer de la Frontera, Spain |

| Occupation | lawyer |

| Known for | politician |

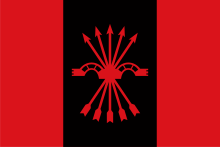

| Political party | Comunión Tradicionalista |

Jesús Elías Francisco Elizalde Sainz de Robles (1907–1980) was a Spanish Carlist politician. He served in the Cortes in two separate strings: during the Second Republic in 1936 and during Francoism in 1954-1958. In 1938-1939 he was a member of Junta Política of Falange Española Tradicionalista, and in 1954-1958 he was a member of FET's Consejo Nacional. In 1942-1944 he headed the regional Carlist Navarrese organization. Politically he sided with the Carlist branch which opted for conciliatory policy towards the Franco regime and leaned towards a monarchist dynastical alliance.

Family and youth

[edit]

Jesús’ ancestors can be traced back only to the early 18th century.[1] His great-great grandfather José Elizalde Martínez de Vidaurre was related to Viana,[2] noted as “maestro ensamblador”;[3] over time the family grew to prosperity, though little is known of his great-grandfather Juan Elizalde Alonso[4] and grandfather Lino María Elizalde Navarro.[5] His father, Fructuoso Elizalde Sabando (1858-1944),[6] was among the most prestigious Viana personalities, listed as “rico propietario”.[7] In the 1890s he entered the Viana ayuntamiento as segundo alcalde[8] and between 1893[9] and 1903[10] he served as mayor of the town. In 1895 Fructuoso married Guadalupe Sainz de Robles (born 1872) from Arnedo;[11] she was daughter to Víctor Sainz de Robles,[12] director of Instituto de Segunda Enseñanza from the nearby Calahorra.[13] The couple settled on the family estate in Viana; they had 6 children, born between 1896 and 1912: Casilda,[14] José María, Jesús,[15] Carmen, Pilar[16] and Ángel Elizalde Sainz de Robles.

Jesús was first educated in Escuela Industrial y de Artes y Oficios in Logroño, where he studied at the turn of the 1910s[17] and 1920s.[18] Following bachillerato at unspecified time he enrolled at the Faculty of Law in the University of Oviedo, where he was recorded in 1927.[19] However, he graduated in jurisprudence at the University of Zaragoza as late as in 1934;[20] none of the sources consulted clarifies why he switched from Asturias to Aragón, why it took him at least 7 years to complete the curriculum and why he majored at a relatively late age of 26.[21] In early 1935 Elizalde was formally incorporated into the Colegio de Abogados of Pamplona, though it is not clear whether he practiced before the outbreak of the Civil War.[22]

At unspecified time Elizalde married María del Socorro Ureña y Mantilla de los Ríos (died 2010).[23] She was daughter to Francisco de Ureña Navas, a locally recognized Andalusian poet and literary critic, publisher and leader of a literary group El Madroño;[24] along maternal line she descended from the well-off Andalusian Mantilla de los Ríos family, owners of numerous landholdings and related to the aristocratic Marqués de Casa Saavedra branch.[25] Jesús and Socorro had no children;[26] after the war they resided in Madrid, though the couple co-owned also a small estate in Vejer de la Frontera.[27] Among Elizalde's relatives his nephew Felipe Zalba Elizalde became a religious and served as bishop of Arequipa;[28] another one, Inocencio Zalba Elizalde, was moderately engaged in Carlism of the 1960s.[29] Jesús’ younger brother, Ángel Elizalde Sainz de Robles, served as requeté and died in combat in 1939; his sister Carmen became member of the Damas Apostólicas congregation.[30]

Republic

[edit]

Elizalde was born into the Carlist family; his father engaged in the movement and mixed with some Navarrese deputies,[31] though he did not hold prestigious positions in the party.[32] It is not clear when Jesús himself became active within Traditionalist ranks. He was first noted as a speaker during Carlist rallies in April 1932, not only in his native Navarre but also in Cantabria[33] and Catalonia,[34] appearing already among party heavyweights like Pradera, Rodezno or Bilbao. In 1933-1934 he was repeatedly noted addressing the crowd, be it in minor Vasco-navarrese locations like Bargota,[35] Lerin,[36] Villava,[37] Haro,[38] Oñate,[39] Arceniega[40] and Laguardia[41] or in larger cities like Vitoria,[42] Pamplona,[43] Palencia,[44] Zaragoza[45] and even in Madrid.[46] Hailed in the party press as “culto abogado”[47] and author of “beautiful lectures”, Elizalde lambasted the Republic as a regime which brought nothing but misery,[48] denounced parliamentarian democracy[49] as a system which turned Spaniards into slaves of caciques and trade-unionists, and declared Marxism and separatism two principal enemies of the country.[50] He praised organicist suffrage,[51] within limits permitted by censorship advocated virtues of traditionalist monarchy[52] and made veiled references to dynastic claim of the Carlist royal pretender, Don Alfonso Carlos.[53]

By mid-1930s Elizalde already gained some prominence within the Navarrese Carlism. In 1934 Luis Arellano, leader of the nationwide party youth,[54] nominated him head of its regional branch.[55] Elizalde started to preside over Traditionalist rallies.[56] By scholars he is counted among the Carlist “rising propagandists” using increasingly violent and intransigent language.[57] Elizalde's rancor was addressed not only against left-wing parties; he denounced Renovación Española as s "general staff without an army"[58] and referred to CEDA as hypocritical “católicos de intereses”,[59] whose failure “fills us with joy”.[60] On the other hand, he made some effort to court supporters of the cedista youth organisation JAP[61] and the Basque Catholics from PNV.[62]

Prior to the 1936 elections Elizalde was a locally known young propagandist, but in course of the campaign he was somewhat unexpectedly elevated to nationwide prominence. Esteban Bilbao, the party tycoon elected to the Cortes from Pamplona in 1931 and 1933, declared himself fed up with parliamentarism and decided not to stand.[63] His place on the list of regional right-wing coalition was offered to Elizalde, the friend of Arellano, who in turn was the protégé of the Navarrese Carlist leader, conde de Rodezno.[64] Unión de Derechas emerged triumphant from the race and all of its candidates were elected; Elizalde gathered 78,159 votes out of 155,699 votes cast[65] and became the youngest member of the 10-member Traditionalist minority in the Cortes. During his brief, 5-month service in the chamber he remained a passive deputy. Not a single time was he noted as taking to the floor; if recorded by the press it was rather because of his presence at Carlist public rallies.[66]

Civil War

[edit]

In the early summer of 1936 Elizalde was actively engaged in the anti-republican conspiracy. At the time the Carlists were divided over terms of access to planned military rising; the faction led by Fal Conde demanded political concessions, the group led by Rodezno preferred to join almost unconditionally. Elizalde formed part of the rodeznistas; in July he travelled to Saint Jean de Luz and managed to win over the claimant.[67] Upon outbreak of hostilities he joined Junta Central Carlista de Guerra de Navarra, the regional wartime executive, and helped to organize requeté troops advancing towards Gipuzkoa.[68] On July 23 he joined the Carlist volunteer units sent to Zaragoza;[69] it is not clear whether he served as requeté or as an accompanying political leader.[70] During next few months he shuttled on propaganda tours across the Nationalist-held zone, first to Teruel (July)[71] and then to Sierra de Guadarrama (August),[72] Burgos,[73] Pamplona (September),[74] Andalusia (October),[75] Navarre, Salamanca (December)[76] and Zamora (January 1937).[77] At that time he was already at the requeté rank of alférez.[78]

In early 1937 Elizalde seemed somewhat uneasy about heavy-handed military policy towards the Carlist executive and asked Junta Central to demand that Fal Conde be allowed return from forced exile;[79] he made unclear hints about would-be rupture between the army the Carlists.[80] He did not form part of the nationwide party leadership and did not participate in a series of crucial meetings debating the threat of forced political unification;[81] eventually he approached the rodeznistas, who advocated compliance with Franco's dictate. In May 1937 the official decree nominated him one of two "asesores políticos" of the newly formed unificated Milicia Nacional.[82] Not exactly within top strata, thus Elizalde became one of 20-odd Carlists on positions of importance within the new state party, Falange Española Tradicionalista.[83]

During the next two years Elizalde vacillated between conciliatory rodeznistas and intransigent falcondistas. In late 1937 the latter considered him a candidate to new Navarrese executive, about to replace the one supposedly sold-out to Franco.[84] Indeed, he publicly voiced unease about Falangist political domination,[85] yet in March 1938 the dictator as part of his political balancing game[86] nominated Elizalde to Junta Política of FET.[87] In the new role he tried to cultivate Carlist identity by focusing on requeté effort at public rallies[88] or lambasting “intolerable” domination of Falangist threads in official propaganda.[89] In February 1939, soon after death of his younger brother had turned into a demonstration of Traditionalist loyalty,[90] Elizalde addressed Franco with a letter which protested marginalisation of Carlism[91] and in correspondence with Fernández-Cuesta argued over local provincial appointments.[92] Shortly prior to Nationalist triumph in the Civil War he handed over his resignation as political advisor to Milicia Nacional; according to some sources at the same time or soon afterwards he resigned also his position in Junta Politica.[93] In February 1939 Fal Conde nominated him to new Navarrese regional executive, led by Joaquín Baleztena and expected to ensure loyalty to the nationwide Carlist leadership.[94]

Early Francoism

[edit]

Following the end of wartime hostilities Elizalde remained moderately active as a Carlist propagandist, yet he did not go off limits permitted by the official Francoist framework.[95] Restrained by dictatorial features of the regime he joined efforts to find non-political ways of expressing Traditionalist identity[96] and contributed to launch of the annual Montejurra ascent.[97] However, he was getting increasingly detached from Navarre; in 1940 Elizalde settled in Madrid,[98] where he joined the local Colegio de Abogados and started to practice as a lawyer.[99] Historiographic works discussing internal squabbles within Navarrese Carlism of the very early 1940s list him as moderately involved.[100] However, as fragmentation within the party ranks triggered another crisis,[101] in 1942 Fal Conde dismissed Baleztena as the Navarrese party leader and nominated Elizalde the new head of Junta Regional.[102]

In his new role Elizalde had to confront growing bewilderment and confusion; local party leaders were increasingly divided over collaboration with Francoist structures and rapprochement with the Alfonsists. Rather scarce evidence related to Elizalde's leadership demonstrates that he preferred a firm stand towards the regime; in 1942 he suggested that Carlists leave all official structures in protest over the Begoña incident;[103] in 1943 he co-signed so-called Reclamación del Poder, an address which demanded instauration of Traditionalist monarchy;[104] in 1944 he voiced in favor of Carlists joining a monarchist conspiracy against Franco.[105] His position on dynastic issues is unclear. Though a trustee of Fal Conde,[106] already in 1943 he was in touch with Rodezno about negotiations with the Alfonsist claimant Don Juan.[107] In 1944 the entire Junta Regional demanded from the regent Don Javier that he calls for a grand Carlist assembly, which in turn would terminate the regency and elect a new king. As Fal Conde and Don Javier rejected the plan, in November 1944 the entire Junta resigned in corpore.[108]

Elizalde did not accompany Rodezno during his 1946 visit to Don Juan[109] and in private correspondence he dwelled upon errors of juanismo against the background of opportunism.[110] However, the same year he co-signed a letter which in polite but firm terms asked Don Javier to terminate the regency.[111] In 1947 he protested to Fal about a pamphlet of Melchor Ferrer, which in aggressive and venomous terms lambasted Rodezno and his pro-juanista leaning.[112] In wake of the Law of Succession campaign Elizalde co-signed a letter to Franco, which pointed to Traditionalist monarchy as the only viable way forward.[113] From time to time he published in El Pensamiento Navarro, trying to cultivate the Carlist identity and Traditionalist contribution to “nuestra Cruzada y la parte decisiva y heroica que en elle tomó Navarra”;[114] in particular he continued to animate the Montejurra ascent.[115] He went on living in Madrid[116] and kept practicing as abogado, in the press listed e.g. as representing various legal entities engaged in juridical proceedings over mining licences;[117] he also competed for posts in executive of the local Bar Association.[118]

Mid-Francoism

[edit]

Though still in his mid-40s, in the early 1950s Elizalde seemed political sidetracked, inactive either in semi-clandestine Carlist structures or in the official Francoist ones. His political activity boiled down to co-signing various letters, e.g. in 1950 about Pamplona ayuntamiento's financial aid to the local Carlist circulo[119] or in 1951 in support of Carlist candidates to the local Pamplonese elections.[120] The first signs of change came in 1953, when he was noted during cultural events in company of vehemently pro-regime offshoot Traditionalists like Jesús Evaristo Casariego.[121] In early 1954 he was received by Franco at a private hearing; nothing is known either about the purpose or the outcome of the meeting.[122] Shortly afterwards he started to appear on semi-official events along the likes of Antonio Iturmendi.[123] For the first time since his 1939 resignation from Junta Nacional, Elizalde firmly re-entered the officialdom when in 1954 Franco appointed him as member of Consejo Nacional of Falange;[124] this in turn automatically ensured his seat in the Cortes.[125]

The term of 6. Consejo Nacional expired in 1955, yet the same year Franco re-appointed Elizalde to the 7. National Council.[126] This time he served the full 3-year term, working in Seccion Educación Popular;[127] as consejero he again received the Cortes ticket in the so-called V. Legislatura, which he held until its expiry 1958.[128] Elizalde's seat in Consejo Nacional was not prolonged in 1958 and following 4 years in somewhat decorative yet still prestigious and nominally key institutions of the Francoist state he again fell off top strata of the regime. None of the sources consulted provides any insight either into a mechanism of Elizalde's political elevation or this of his political demise.[129] There are no details available referring to his 1954-1958 Consejo Nacional[130] or Cortes activity.[131] He was not noted in newspapers of the era; the only case his name appeared in the press was related to Elizalde's own article in Punta Europa, a Traditionalist periodical headed by Vícente Marrero.[132]

It is not clear whether cessation of Elizalde's Cortes career had anything to do with a so-called Acto de Estoril of 1957, when some 50 Traditionalists visited Don Juan and declared him the legitimate Carlist heir.[133] Due to his wartime record and former position in the Navarrese executive Elizalde was among the most eminent “estorilos”; the act completed his 15-year journey to the Juanista camp and confirmed his definitive breakup with the Javierista branch of Carlism. However, it proved to have been Elizalde's political swan song. He did not enter Consejo Privado or other institutions grouping politicians from Don Juan's inner circle, and he soon disappeared from public life altogether; it is not clear whether he was marginalized or deliberately withdrew into privacy. Barely 50-year-old, he was no longer featured in the media and is not listed by historiographic works as engaged in politics, be it in the Francoist, Juanista or Carlist structures. The exception is an episode from 1967, when he briefly served as vice-president of Hermandad de Cristo Rey de Requetés Ex-Combatientes, a pro-Juanista organisation of Carlist wartime volunteers.[134]

See also

[edit]Footnotes

[edit]- ^ along the patriline the great-great-great grandfather of Jesús was Antonio Elizalde, married to María Ana Martínez de Vidaurre, Antonio Elizalde entry, [in:] Geneaordonez service, available here

- ^ in 1733 he married María Gerónima Alonso Perez del Notario; both were from Viana, Joseph Elizalde Martinez de Vidaurre, [in:] Geneaordonez service, available here

- ^ Juan Cruz Labeaga Mendiola, Viana celebra los acontecimientos de la monarquía, [in:] Cuadernos de etnología y etnografía de Navarra 39/82 (2007), p. 80

- ^ in 1805 he married Jacoba Josefa Navarro Sainz de Urbina; both were from Viana, Juan Elizalde Alonso entry, [in:] Geneaordonez service, available here

- ^ in 1853 he married Casilda Sabando Zalduendo, also from Viana, Lino Maria Elizalde Alonso, [in:] Geneaordonez service, available here

- ^ ABC 14.01.44, available here Archived 2019-07-14 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ El Eco de Navarra 28.11.97, available here

- ^ La Rioja 22.02.90, available here

- ^ Elizalde entry, [in:] HeraldicaDeViana service, available here

- ^ La Rioja 26.11.03, available here; in 1904 he served in the ayuntamiento, but not as a mayor, La Rioja 03.01.04, available here

- ^ Elizalde Sainz de Robles, Jesús [Caja 400 AHICAM 1.1 Exp. 12420], [in:] Patrimonio documental del Ilustre Colegio de Abogados de Madrid service, available here

- ^ another source claims that in 1892 he married María Carmen Sainz de Robles García, a girl from Pamplona, Fructuoso Elizalde Sabando entry, [in:] Geneaordonez service, available here

- ^ El Aralar 23.02.95, available here, El Eco de Navarra 28.11.97, available here; she was daughter to Casilda García from Burgos, Elizalde Sainz de Robles, Jesús [Caja 400 AHICAM 1.1 Exp. 12420], [in:] Patrimonio documental del Ilustre Colegio de Abogados de Madrid service, available here

- ^ born 1896, died 1993, Casilda Elizalde Sainz de Robles entry, [in:] Geneaordonez service, available here

- ^ full name Jesús Elias Francisco Elizalde y Sainz de Robles, Elizalde Sainz de Robles, Jesús [Caja 400 AHICAM 1.1 Exp. 12420], [in:] Patrimonio documental del Ilustre Colegio de Abogados de Madrid service, available here

- ^ ABC 14.01.44, available here

- ^ La Rioja 26.05.18, available here

- ^ La Rioja 28.05.21, available here

- ^ La Atalaya 14.07.27, available here

- ^ Elizalde Sainz de Robles, Jesús [Caja 400 AHICAM 1.1 Exp. 12420], [in:] Patrimonio documental del Ilustre Colegio de Abogados de Madrid service, available here

- ^ perhaps Elizalde was tempted by career on stage. During periods corresponding to his academic years a student named “Jesús Elizalde” was noted by Cantabrian and Aragonese press as an actor in amateur theatres, El Cantabrico 07.05.27, available here, La Voz de Aragon 01.05.30, available here

- ^ Elizalde Sainz de Robles, Jesús [Caja 400 AHICAM 1.1 Exp. 12420], [in:] Patrimonio documental del Ilustre Colegio de Abogados de Madrid service, available here

- ^ Socorro Mantilla de los Ríos y Mantilla de los Ríos entry, [in:] Geneanet service, available here

- ^ D. Francisco de Paula Ureña Navas y el grupo literario "El Madroño", [in:] Giennium: revista de estudios e investigación de la Diócesis de Jaén 11 (2008), pp. 169-210

- ^ he mother was Socorro Mantilla de los Ríos, by maternal line granddaughter to Carlos Mantilla de los Ríos y Férnandez de Henestrosa, himself son to Carlos Mantilla de los Ríos y Valderrama, 8th Marqués de Casa Saavedra, Socorro Mantilla de los Ríos y Mantilla de los Ríos entry, [in:] Geneanet service, available here

- ^ no children were listed either in the 1980 obituary of Elizalde or in the 2010 obituary of his wife, see ABC 24.02.80, available here, and ABC 20.11.10, available here

- ^ B.O.E. 20.11.67, available here

- ^ ABC 23.12.80, available here

- ^ he contributed to the monthly Montejurra and in 1965 briefly served as jefe regional adjunto del requeté de Navarra, Mercedes Vázquez de Prada Tiffe, La oposición al colaboracionismo carlista en Navarra, [in:] Príncipe de Viana 76/262 (2015), p. 802

- ^ ABC 24.02.80, available here

- ^ e.g. as in 1902 he welcomed in Viana a Carlist deputy from Estella Joaquín Llorens and was referred to as his coreligionario, La Rioja 14.10.02, available here

- ^ Fructuoso Elizalde was not a very principled and intransigent Carlist, since in 1903 he welcomed Alfonso XIII in Viana; La Epoca 01.09.03, available here

- ^ Julián Sanz Hoya, De la resistencia a la reacción: las derechas frente a la Segunda República (Cantabria, 1931-1936), Santander 2006, ISBN 9788481024203, p. 136

- ^ Robert Vallverdú i Martí, El carlisme català durant la Segona República Espanyola 1931-1936, Barcelona 2008, ISBN 9788478260805, p. 101

- ^ El Cantábrico 07.05.27, available here

- ^ Pensamiento Alaves 09.05.33, available here, Pensamiento Alaves 13.01.34, available here

- ^ El Siglo Futuro 12.10.33, available here

- ^ Pensamiento Alaves 15.03.34, available here

- ^ Pensamiento Alaves 14.06.34, available here

- ^ Pensamiento Alaves 29.08.34, available here

- ^ Pensamiento Alaves 10.09.34, available here

- ^ Pensamiento Alaves 26.02.34, available here

- ^ La Gaceta de Tenerife 28.03.33, available here

- ^ El Diario Palentino 29.01.34, available here

- ^ El Siglo Futuro 16.05.33, available here

- ^ El Siglo Futuro 27.01.34, available here

- ^ El Cantábrico 07.05.27, available here

- ^ Pensamiento Alaves 28.03.33, available here

- ^ Pensamiento Alaves 26.02.36, available here

- ^ El Diario Palentino 29.01.34, available here

- ^ El Siglo Futuro 16.05.33, available here

- ^ La Voz de Aragón 14.05.33, available here

- ^ compare Elizalde’s phrases abough bringing Carlist colors to Palacio de Oriente or his homage to “an elderly man of fatherly words and royal breath”, a hardly veiled reference to the Carlist king Don Alfonso Carlos, Pensamiento Alaves 01.06.34, available here

- ^ Arellano’s role was officially named Secterario General de Juventudes

- ^ El Siglo Futuro 08.06.34, available here. None of the sources consulted suggests that Elizalde was engaged in requeté buildup. The local Viana head of Carlist paramilitary militia was Mauro Galar, Antonio de Lizarza Iribarren, Memorias de la conspiración, [in:] Navarra fue la primera: 1936-1939, Pamplona 2006, ISBN 8493508187, p. 45

- ^ Hoja Oficial de Lunes 26.02.34, available here

- ^ Martin Blinkhorn, Carlism and Crisis in Spain 1931-1939, Cambridge 2008, ISBN 9780521086349, p. 219. In May 1933 May in Estella Elizalde hailed Montejurra as an inspiration “para hacer volver a la memoria las víctimas de la Tradición que sólo pedían un puñado de tierra para que cubriese sus cadáveres y una rama de nuestros árboles para hacer la cruz y colocarla en su sepultura”, Francisco Javier Caspistegui Gorasurreta, Montejurra, la construcción de un símbolo, [in:] Historia contemporánea 47 (2013), p. 546

- ^ Blinkhorn 2008, p. 200

- ^ Elizalde distinguished between “católicos de interese y nosotros somos los católicos de ideales”, El Sol 28.05.35, available here

- ^ Blinkhorn 2008, p. 202

- ^ see Elizalde’s 1935 efforts to distinguish between old and overcautious CEDA leader Gil-Robles and his courageous youth organisation JAP, Pensamiento Alaves 20.08.35, available here

- ^ Pensamiento Alaves 02.09.35, available here

- ^ Alberto García Umbón, Tudela desde las elecciones de febrero de 1936 hasta el inicio de la guerra civil, [in:] Príncipe de Viana 66/234 (2005), p. 239

- ^ El Diario Palentino 20.01.36, available here

- ^ see the official Cortes service, available here

- ^ El Siglo Futuro 17.03.36, available here

- ^ Antonio Atienza Peñarrocha, Africanistas y junteros: el ejercito español en Africa y el oficial José Enrique Varela Iglesias [PhD thesis Universidad Cardenal Herrera – CEU], Valencia 2012, p. 995

- ^ Juan Carlos Peñas Bernaldo de Quirós, El Carlismo, la República y la Guerra Civil (1936-1937). De la conspiración a la unificación, Madrid 1996, ISBN 9788487863523, p. 211

- ^ Peñas Bernaldo 1996, p. 178, Julio Aróstegui, Combatientes Requetés en la Guerra Civil española, 1936-1939, Madrid 2013, ISBN 9788499709970, p. 405

- ^ Pensamiento Alaves 24.07.36, available here, see also documents at Elizalde Sainz de Robles, Jesús [Caja 400 AHICAM 1.1 Exp. 12420], [in:] Patrimonio documental del Ilustre Colegio de Abogados de Madrid service, available here

- ^ José Manuel Azcona Pastor, Matteo Re, Juan Francisco Carmona Torregrosa, Guerra y Paz. La Sociedad Internacional entre el Conflicto y la Cooperación, Madrid 2013, ISBN 9788490316870, p. 217

- ^ Pensamiento Alaves 08.08.36, available here

- ^ Manuel Sanchez Forcada, Diario de campaña de un requeté pamplonés, [in:] Príncipe de Viana 64/230 (2003), p. 649. The author refers to an “Elizalde” who used to be „presidente de las juventudes Carlistas de Navarra”

- ^ Pensamiento Alaves 15.09.36, available here

- ^ La Unión 14.11.36, available here

- ^ El Adelanto 15.12.36, available here

- ^ Imperio 09.01.37, available here

- ^ Pensamiento Alaves 15.09.36, available here

- ^ in February 1937 Feb Elizalde co-signed a letter to the Navarrese Carlist executive, Junta Central, requesting that they demand from Franco that Fal gets relieved from exile; the Junta responded that given the circumstances, such a demand would be imprudent, Peñas Bernaldo 1996, p. 247

- ^ Elizalde he wanted action “before the affair can leak out”, Blinkhorn 2008, p. 277

- ^ Elizalde is not listed detailed account of various meetings of Carlist executive in February, March and April 1937, see Peñas Bernaldo 1996

- ^ a professional military José Monasterio was nominated jefe of the Militia, while a Falangist Dario Gazapo and a Carlist Ricardo Rada were his deputies; asesores políticos were Agustín Aznár from Falange and Elizalde as a Carlist, El Día de Palencia 12.05.37, available here

- ^ other highly positioned Carlists in FET were Rodezno, Florida, Mazon and Arellano (members of Junta Política), Gaiztarro, Llopart, Oreja and Urraca (heading section of hacienda, transportes, sanidad and frentes/hospitales respectively), Echandi Indart (secretario de despacho), Rada (subjefe de milicia), Eladio Esparza (vicepresidente del consejo). Provincial FET jefes were Carcer (Valencia), Oriol (Bizacay), Muñoz Aguilar (Gipuzkoa), Echave Sustaeta (Alava), Herrera Tejada (Logroño) and Garzón (Granada), Blinkhorn 2008, p. 292

- ^ Manuel Martorell Pérez, La continuidad ideológica del carlismo tras la Guerra Civil [PhD thesis in Historia Contemporanea, Universidad Nacional de Educación a Distancia], Valencia 2009, p. 152

- ^ in February 1938 Elizalde published in El Pensamiento Navarro an article, which contained a vailed protest against the Falangist monopoly, El Avisador Numantino 02.02.38, available here

- ^ one scholar attributes Elizalde’s elevation to “sabia dosificación” of representatives of various political groupings, Gonzalo Redondo, Historia de la Iglesia en España, 1931-1939, Madrid 1993, ISBN 9788432130168, p. 436

- ^ Heraldo de Zamora 10.03.38, available here

- ^ El Adelanto 19.08.38, available here, Diario de Burgos 02.09.38, available here, Lizarza Iribarren 2006, pp. 149-150, 155

- ^ many historiographic works note his protest against a Francoist propaganda movie of early 1939; it presented the 1936-1937 conquest of the Northern zone with emphasis on Falange and almost no mention at all about the Carlist requeté. Depending upon sources, Elizalde either protested to Junta Política, or to Fernandez Cuesta, or to Franco, Emeterio Diez Puertas, El montaje del franquismo: la política cinematográfica de las fuerzas sublevadas, Madrid 2002, ISBN 9788475844824, p. 270, Mercedes Peñalba Sotorrío, Entre la boina roja y la camisa azul, Estella 2013, ISBN 9788423533657, p. 144

- ^ Angel Elizalde died in combat in Extremadura in January 1939. During his funeral 5 Carlist requeté captains - Luis Elizalde, José Lampreave, Honorato Lázaro, Antonio Sánchez and Carlos Ciganda - pledged to remain faithful to “las auténticas jerarquías de la Gloriosa Comunión Tradicionalista”, Martorell Pérez 2009, p. 74, Manuel Martorell Pérez, Navarra 1937-1939: el fiasco de la Unificación, [in:] Príncipe de Viana 69 (2008), p. 429

- ^ “Madrid, toda para la Falange; Valencia, todo para la Falange; Barcelona todo para la Falange y mientras tanto los Requetés muriendo por conquistar tierras y para lo que ellos creen una España sin parcialidades ni egoísmos partidistas”, Robert Vallverdú i Martí, La metamorfosi del carlisme català: del "Déu, Pàtria i Rei" a l'Assamblea de Catalunya (1936-1975), Barcelona 2014, ISBN 9788498837261, p. 74; “¡Qué se pretende con todo esto! -exclama en otro párrafo: ¿Anular al Requeté o poner a España en las manos de la antigua Fralange Española?”, Martorell Pérez 2009, p. 136

- ^ in March Elizalde protested about FET appointments in Lerida, Joan Maria Thomàs, Las Falanges de Barcelona entre 1934 y 1940, [in:] Historia y Fuente Oral 7 (1992), p. 107

- ^ “dejandome marchar a cumplir mis deberes de español en otros sitios”, Martorell Pérez 2009, p. 136. The issue is not entirely clear. In 1939 July one newspaper referred to him as member of Junta Política, El Diario Palentino 24.07.39, available here

- ^ Aurora Villanueva Martínez, Organizacion, actividad y bases del carlismo navarro durante el primer franquismo [in:] Geronimo de Uztariz 19 (2003), p. 101

- ^ Pensamiento Alaves 01.05.39, available here

- ^ apart from the Montejurra ascent, other non-political measures adopted were opening of Museo de Recuerdos Históricos and foundation of Hermandad de Caballeros Voluntarios de la Cruz, Villanueva Martínez 2003, p. 102

- ^ Azul 05.05.39, available here

- ^ Elizalde settled in Madrid at Calle de Maldonado 15, Elizalde Sainz de Robles, Jesús [Caja 400 AHICAM 1.1 Exp. 12420], [in:] Patrimonio documental del Ilustre Colegio de Abogados de Madrid service, available here

- ^ Elizalde Sainz de Robles, Jesús [Caja 400 AHICAM 1.1 Exp. 12420], [in:] Patrimonio documental del Ilustre Colegio de Abogados de Madrid service, available here

- ^ compare Aurora Villanueva Martínez,El carlismo navarro durante el primer franquismo, 1937-1951, Madrid 1998, ISBN 9788487863714. Note that at the time there were 4 other Carlists named Elizalde active in Navarre: Rafael Elizalde Munárriz, Juan Elizalde Viscarret, Carlos Elizalde Zabalza and Luis Elizalde Sarasate

- ^ in 1941 Joaquín Baleztena refused to transfer some of (nominally) his shares in El Pensamiento Navarro to other individuals suggested by Fal Conde; in return, Fal released Baleztena from the Navarrese jefatura

- ^ Villanueva Martínez 2003, p. 105

- ^ Villanueva Martínez 2003, pp. 105-106

- ^ César Alcalá, D. Mauricio de Sivatte. Una biografía política (1901-1980), Barcelona 2001, ISBN 8493109797, p. 53, Vallverdú i Martí 2014, p. 96

- ^ Alcalá 2001, p. 57, Martorell Pérez 2009, p. 432

- ^ in 1943 Elizalde represented Fal (unable to attend due to his home arrest) on a wedding, ABC 29.10.43, available here

- ^ Manuel Santa Cruz Alberto Ruiz de Galarreta, Apuntes y documentos para la Historia del Tradicionalismo Español, vol. 4-5, Sevilla 1942, pp. 133, 145

- ^ Villanueva Martínez 2003, p. 107, Aurora Villanueva Martínez, El carlismo navarro durante el primer franquismo, 1937-1951, Madrid 1998, ISBN 9788487863714, pp. 229-232. Cruz Ancín was appointed as acting Navarrese jefé; formal Elizalde’s successor was Mariano Lumbier, appointed in 1947, Villanueva Martínez 2003, p. 108

- ^ the only Navarros present were Arellano and Ortigosa, Villanueva Martínez 2003, p. 109

- ^ Jacek Bartyzel, Nic bez Boga, nic wbrew tradycji, Radzymin 2015, ISBN 9788360748732, p. 252

- ^ Villanueva Martínez 1998, p. 275

- ^ Villanueva Martínez 1998, p. 305

- ^ Villanueva Martínez 1998, p. 315

- ^ Elizalde hailed the Montejurra ascent as “recio sabor de rito religioso popular que rememora y conmemora en símbolo, incruentamente, un hecho real, magnifico y cruento: nuestra Cruzada y la parte decisiva y heroica que en elle tomó Navarra”, El Pensamiento Navarro 02.05.48, referred after Francisco Javier Caspistegui Gorasurreta, El naufragio de las ortodoxias. El carlismo, 1962–1977, Pamplona 1997; ISBN 9788431315641, p. 285

- ^ in 1951 Elizalde again wrote to El Pensamiento Navarro about Montejurra, “día de la oración de los que perdieron a sus hijos, a sus maridos, a sus hermanos, en nuestra Cruzada, para ganarlos – si es cierta nuestra cristiana esperanza – en el cielo”, El Pensamiento Navarro 05.05.51, referred after Caspistegui Gorasurreta 1997, p. 285

- ^ ABC 28.05.48, available here

- ^ Boletín Oficial de la Provincia de Santander 26.01.44, available here

- ^ ABC 28.05.48, available here

- ^ Villanueva Martínez 1998, p. 436

- ^ Villanueva Martínez 1998, p. 467

- ^ ABC 03.06.53, available here

- ^ Imperio 25.02.54, available here

- ^ La Vanguardia Española 24.04.54, available here

- ^ ABC 30.07.54, available here, B.O.E. 29.07.54, available here

- ^ see the official Cortes service, available here

- ^ Imperio 11.05.55, available here

- ^ La Vanguardia Española 19.06.56, available here

- ^ see the official Cortes service, available here

- ^ Elizalde was one of 79 traditionalists in the Francoist Cortes, some 3% of the total, Miguel Angel Giménez Martínez, Las Cortes de Franco o el Parlamento imposible, [in:] Trocadero: Revista de historia moderna y contemporanea 27 (2015), p. 78

- ^ a detailed study on Consejo Nacional does not mention Elizalde, see Miguel Ángel Giménez Martínez, El Consejo Nacional del Movimientola "cámara de las ideas" del franquismo, [in:] Investigaciones históricas: Época moderna y contemporánea 35 (2015), pp. 271-297

- ^ a study on the Francoist Cortes ignores Elizalde, see Giménez Martínez 2015

- ^ Jesús Elizalde, La fiesta de los Mártires de la Tradición, [in:] Punta Europa 1956/3, pp. 18-20, available here

- ^ Alcalá 2001, p. 139, Caspistegui Gorasurreta 1997, p. 24, Blinkhorn 2008, p. 302, Martorell Pérez 2009, p. 186

- ^ ABC 12.10.67, available here

Further reading

[edit]- Martin Blinkhorn, Carlism and Crisis in Spain 1931-1939, Cambridge 2008, ISBN 9780521086349

- Aurora Villanueva Martínez, El carlismo navarro durante el primer franquismo: 1937-1951, Madrid 1998, ISBN 9788487863714

External links

[edit]- Basque Carlist politicians

- Carlists

- Members of the Congress of Deputies of the Second Spanish Republic

- Members of the Cortes Españolas

- Politicians from Navarre

- Spanish propagandists

- Roman Catholic activists

- Spanish anti-communists

- 20th-century Spanish lawyers

- Spanish monarchists

- Spanish people of the Spanish Civil War (National faction)

- Spanish Roman Catholics

- University of Zaragoza alumni

- 1907 births

- 1980 deaths