Jean Valentine (bombe operator)

Jean Millar Valentine | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | Jean Millar Valentine 7 July 1924 Perth,_Scotland, Scotland |

| Died | 17 May 2019 (aged 94) Henley-on-Thames, England |

| Nationality | Scottish |

| Citizenship | British |

| Known for | Bombe operation as a Wren at Bletchley Park |

| Spouse |

Clive Ingram Rooke

(m. 1946–1998) |

| Children | 2 |

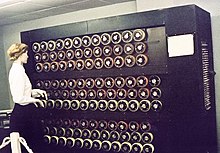

Jean Millar Valentine, later Jean Millar Rooke (7 July 1924 – 17 May 2019) was an operator of the Bombe decryption device in Hut 11 at Bletchley Park in England, designed by Alan Turing and others during World War II.[1] She was a member of the 'Wrens' (Women's Royal Naval Service, WRNS).[2] She was later involved in the reconstruction of the Bombe at Bletchley Park Museum and gave tours there.[3]

Early life

[edit]Jean Millar Valentine was born in Perth, Scotland on 7 July 1924 to Mr and Mrs James Valentine. She became a member of the WRNS during World War II and was recruited to work in Bletchley Park at the age of 18. Valentine later said that moving down to London was a new experience for her, as she had never been out of Scotland up to that point.

Career in code breaking

[edit]Valentine is one of many women recruited to work at Bletchley Park during the war.[4] During this time, she lived in Steeple Claydon in Buckinghamshire. She started working on 15 shillings (75 pence) a week. Along with her co-workers, she signed the Official Secrets Act, and remained quiet about her war work until the mid-1970s. Churchill referred to them as "the geese who laid the golden egg and never cackled".[5]

Valentine later described how no one would ever talk about what they were doing when outside of Bletchley Park. She worked in Hut 11, and recalled how there would be "five machines within the hut, ten girls and one petty officer that would be in charge of the telephone".[6][7] She was four foot ten inches (1.47m) in height and required a special footstool to operate the top rotors.[8]

She was trained to decrypt Japanese codes and was posted to Ceylon (now Sri Lanka) where she spent 15 months working on Japanese meteorological reports. While there, she met Clive Rooke, a seafire pilot in the Royal Navy, whom she married in 1945.[8][9]

Valentine kept silent about her work on the Bombe until the 1970s when details began to emerge in public. Thereafter, she was an enthusiastic participant in reunions at Bletchley Park.[10] Valentine was involved with the reconstruction of the Bombe at Bletchley Park Museum, completed in 2006.[3][11] In 2006, she said: "Unless people come pouring through the doors, a vital piece of history is lost. The more we can educate them, the better."[12]

Valentine volunteered as a tour guide at the Bletchley Park Museum, demonstrating the reconstructed Bombe.[13][14][15][16][17] In 2011, she demonstrated the Bombe to the Queen and the Duke of Edinburgh.

On 24 June 2012, Valentine spoke about her wartime experiences at Bletchley Park and elsewhere as part of a Turing's Worlds event to celebrate the centenary of the birth of Alan Turing, organised by the Department for Continuing Education's Rewley House at Oxford University in cooperation with the British Society for the History of Mathematics (BSHM).[18][19]

Recognition and awards

[edit]Valentine is commemorated on the Bletchley Park Roll of Honour, which contains a digital copy of her service certificate and a short memoir.[9] She featured on a St Vincent and Grenadines stamp commemorating the 60th Anniversary of D-Day in 2004.[20] In 2009, she and other veterans were presented with a medal from GCHQ in recognition of their wartime service.[20]

Later life and death

[edit]Valentine latterly lived in Henley, Oxfordshire. She died in May 2019 at the age of 94.[20][21]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ ComputerHeritage (14 March 2013). "Operating the Bombe: Jean Valentine's story". YouTube. Retrieved 28 July 2014.

- ^ Lewis, Katy (3 June 2009). "Breaking the codes: Former Bletchley Park Wren, Jean Valentine, reveals exactly what went on at the World War II codebreaking centre". Beds, Herts & Bucks. BBC. Retrieved 28 July 2014.

- ^ a b Fenton, Ben (7 September 2006). "Bletchley hums again to the Turing Bombe". The Daily Telegraph.

- ^ The Women of Bletchley Park, Finding Ada, 26 July 2009.

- ^ Thampson, Kenneth W. (1984). "Martin Gilbert. Winston S. Churchill. Volume VI. Finest Hour 1939-1941. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Co.. 1983. Pp. xx. 1308. $39.00". Albion. 16 (3): 348–351. doi:10.2307/4048800. ISSN 0095-1390. JSTOR 4048800.

- ^ Fessenden, Marissa. "Women Were Key to WWII Code-Breaking at Bletchley Park". Retrieved 8 March 2018.

- ^ computingheritage (14 March 2013). "Operating the Bombe: Jean Valentine's story". Retrieved 8 March 2018 – via YouTube.

- ^ a b "Jean Valentine (1924 - 2019)". The National Museum of Computing. 18 June 2019. Retrieved 16 October 2024.

- ^ a b "Roll of Honour". UK: Bletchley Park. Retrieved 16 October 2024.

- ^ 'Geese' cackle over Enigma: British code breakers reunite to celebrate secret work that helped Allies defeat Nazis, The Star, Toronto, Canada, 25 March 2009.

- ^ What to see at Bletchley Park: Bombe Rebuild Project Archived 5 November 2013 at the Wayback Machine, Bletchley Park, UK.

- ^ Addley, Esther (7 September 2006). "Back in action at Bletchley Park, the black box that broke the Enigma code". The Guardian.

- ^ Jean Valentine explains the bombe on YouTube.

- ^ Jean Valentine explains the bombe[permanent dead link], CastTV.

- ^ BCSWomen trip to Bletchley Park, BCSWomen, UK, 8 May 2008.

- ^ "The geese that laid the golden egg – but never cackled – Winston Churchill". Skirts and Ladders. 26 July 2009. Archived from the original on 14 March 2016.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ Feature: Decoding Bletchley Park's history, Gizmag Emerging Technology Magazine.

- ^ "Driving Miss Valentine". Diaphania.blogspirit.com. Blogspot. 6 July 2012. Retrieved 3 September 2012.

- ^ Valentine, Jean (2017). "A Wren's eye view". In Copeland, Jack; et al. (eds.). The Turing Guide. Oxford University Press. pp. 125–127. ISBN 978-0-19-874783-3.

- ^ a b c "Obituaries: Jean Rooke (née Valentine), wartime codebreaker". Henley Standard. 3 June 2019.

- ^ "Death Notice: Jean Millar Rooke". Bucks Free Press. 31 May 2019.

External links

[edit]- Roll of Honour: List of the men and women who worked at Bletchley Park and the Out Stations during World War II, archived from the original on 18 May 2011, retrieved 9 July 2011