James Young Simpson (diplomat)

James Young Simpson | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 3 August 1873 Edinburgh, Scotland |

| Died | 20 May 1934 (aged 60) Edinburgh, Scotland |

| Pen name | J. Y. Simpson |

| Occupation |

|

| Genre | non-fiction, biography, theology |

| Spouse | Helen Huntingdon Day |

Professor James Young Simpson (3 August 1873 – 20 May 1934) FRSE FRSSA FRAI DJur(Hon) DSc(Hon) was a Scottish zoologist, writer, diplomat, biographer and theologian. After World War I, he was instrumental in establishing the Baltic states and Finland as independent nations.

Life

[edit]James Young Simpson was born at 52 Queen Street in Edinburgh on 3 August 1873 to Margaret Stewart Barbour, sister of Alexander Hugh Freeland Barbour, and Sir Alexander Russell Simpson (1835–1916), professor of midwifery at the University of Edinburgh.[1] His father was a nephew of his namesake, James Young Simpson, the first person to use chloroform as an anesthetic on humans. The family lived at 52 Queen Street, a property inherited from his great-uncle.

Simpson was educated at George Watson's College, Edinburgh and the University of Edinburgh, which he attended from 1891 to 1894, graduating with an MA.[2] After two summers as a research student at Christ's College, Cambridge (1899/1900), he completed his DSc in 1901 at the University of Edinburgh.[1][3]

From 1899, he lectured in natural science at the University of Edinburgh. He was given his professorship in 1904.[4]

In 1900 he was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society of Edinburgh. His proposers were James Cossar Ewart, Sir William Turner, Sir John Murray, and Alexander Buchan.

In 1910, he was living at 25 Chester Street in Edinburgh's West End.[5]

He died on 20 May 1934 in Edinburgh. He is buried with his parents in the south-west section of Grange Cemetery close to the rear embankment behind the central vaults.

Family

[edit]He married Helen Huntington Day of Indianapolis, Indiana, US.[citation needed][when?]

His younger brother was George Freeland Barbour Simpson.

Work

[edit]As a boy, he visited Paris with his father and was introduced to Louis Pasteur. Pasteur laid his hand on Simpson's head and exclaimed: "Travaillez, mon ami, travaillez!" [Work, my friend, work!] Turning to the father, he said "A-t-il dit, Oui?" [Has he said, yes?] Simpson seems to have implemented Pasteur's injunction throughout his life.[6]

In his writings, his dominant interest lay in showing the connection between science and religion. In his view, there is no contradiction between these, and he views Christianity as the natural outcome of man's evolutionary progress. Jesus Christ is "the fulfillment of all that went before. . . He is the Alpha and Omega of strictly human history." and so on.[7] In a later book, Nature: Cosmic, Human and Divine (1929), Simpson argues that religion results from the confrontation of Mind with the Infinite Energy of the universe as suggested by Heisenberg's indeterminacy principle.[8]

Association with Russia and the Baltic States

[edit]Simpson's association with Russia began when Prince Nicholas Galitsyn visited Edinburgh in the early 1890s. Simpson befriended him and accompanied him on a visit to Siberia in the summer and autumn of 1896.[9]

The object of the journey was to visit Siberian prisons and distribute bibles and other religious works to prisoners. Simpson made elaborate notes on the topography, agriculture, and customs of Siberia. These notes led to the publication of the book, Side-lights on Siberia in 1898. Subsequent books on Russia resulted from his regular visits to that country.

In September 1910, Simpson accompanied his father to a medical congress in Petrograd (now St. Petersburg) in Russia. On this one week's visit, he met Baron Nicolai and other Christians who were impressed by his reconciliation of Christianity with science.[10] His last visits to Russia were in 1916 and April/May 1917 before the Revolution took place.[11]

In 1919, Simpson worked with the British Delegation to the Peace Conference at Versailles to ensure that the Baltic States and Finland were established as independent states.[12] He was subsequently given awards by these countries in recognition of his services. His last visit to the Baltic States was in June/July 1932, when he received the honorary degree of Doctor of Law (D.Jur.) at the University of Tartu.[13]

Professional and Other Posts

[edit]- Lecturer in Natural Science, Trinity College, Glasgow, 1900–1934;[14]

- Professor in Natural Science, New College, Edinburgh, 1904–1934;[15]

- Terry Lecturer, Yale University, 1929, and other lectureships in the United States;[16]

- Fellow of Royal Society of Edinburgh;

- Fellow of Royal Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland;

- Fellow of Royal Scottish Society of Arts.

- Member of Royal Company of Archers (King's Bodyguard for Scotland);

- Vice-President, Royal Scottish Geographical Society;

- Vice-President, Robert Louis Stevenson Society;

- President, West Edinburgh Liberal Association (1931);[13]

- Fellow and Councillor of Royal Zoological Society of Scotland;

- President, World Brotherhood Federation;

- Member of Political Intelligence Department, at first in Bureau (Ministry) of Information, latterly in Foreign Office, 1917–19;

- Member of British Delegation to the Peace Congress at Paris, attached Political Section, 1919;

- President, Latvian-Lithuanian Frontier Court of Arbitration, 1921

Professional honours

[edit]- Commander, 1st Class, Finnish Order of the White Rose;[17]

- Estonian Liberty Cross, 1st Class, 1920;

- Latvian Order of the Three Stars, 2nd Class, 1925;

- Commander, Lithuanian Order of Gediminas, 1928.

Publications

[edit]- Side-Lights on Siberia: Some Account of the Great Siberian Railroad, the Prisons and Exile System. Edinburgh & London: W. Blackwood & Sons, 1898

- Henry Drummond, Edinburgh: Oliphant, Anderson and Ferrier, 1901, ("Famous Scots Series")

- The Spiritual Interpretation of Nature. London: Hodder and Stoughton, 1923. [1912]

- Self-Discovery of Russia. London: Constable, 1916

- Some notes on the State Sale-Monopoly and Subsequent Prohibition of Vodka in Russia. 1918

- Man and the Attainment of Immortality. London: Hodder & Stoughton, 1922.

- Contribution to Vol. VI of History of the Peace Conference at Paris, ed. by Harold Temperley. London: H. Frowde, and Hodder & Stoughton, 1920–24.

- Landmarks in the Struggle Between Science and Religion. London: Hodder & Stoughton, 1925.

- The Saburov memoirs: or, Bismarck and Russia; Being Fresh Light on the League of the Three Emperors, 1881, by Peter Alexandrovich Saburov. Translated and edited with an introduction by J.Y.Simpson, Cambridge University Press, 1929.

- Nature: Cosmic, Human and Divine. Oxford: OUP, 1929, (Dwight Harrington Terry Foundation Lectures on religion in the light of science and philosophy, 1929).

- World Politics and the Kingdom of God. John Clifford lecture; 1933

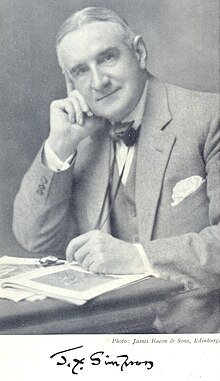

- The Garment of the Living God. Studies in the relations of science and religion. The Sprunt lectures. With a 'Memoir' by George Freeland Barbour. [With a portrait.] London: Hodder & Stoughton, 1934.) The above photograph is taken from the frontispiece portrait in this book.

- The Thoughtful Minute. [Essays. Reprinted from "The Weekly Scotsman".] London 1937.

- Numerous articles in literary magazines and scientific journals.

Sources

[edit]- Who Was Who, Vol. III, p. 1239. London: A & C Black, 1920–2008; online edn, Oxford University Press, Dec 2007

- "Memoir" by George Freeland Barbour in the book: The Garment of the Living God (1934). The above photograph is from the frontispiece of this book.

- British Library catalogue: www.bl.uk

- National Library of Scotland catalogue, nls.uk. Accessed 5 November 2022.

References

[edit]- ^ a b "Simpson, James Young (3 Aug. 1873–20 May 1934), Professor of Natural Science in New College, and Lecturer in the University, Edinburgh", Who Was Who, Oxford University Press, 1 December 2007, doi:10.1093/ww/9780199540884.013.u217101, ISBN 978-0-19-954089-1, retrieved 15 May 2019

- ^ Memoir by G.F. Barbour in the book: The Garment of the Living God (1934) pp. 18–19.

- ^ Simpson, James Young (1901). "Observations on some outstanding features of protozoan life".

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Biographical Index of Former Fellows of the Royal Society of Edinburgh 1783–2002 (PDF). The Royal Society of Edinburgh. July 2006. ISBN 0-902-198-84-X. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 27 June 2018.

- ^ Edinburgh Post Office Directory, 1910

- ^ 'Memoir', p. 18.

- ^ Man and the Attainment of Immortality. London: Hodder & Stoughton, 1922, p. 260.

- ^ Nature: Cosmic, Human and Divine. Oxford: OUP, 1929, p.115f.

- ^ 'Memoir', p.24f. This Prince Nicholas Galitzin was not the famous Prince Nicholas Galitzine who was the last Tsarist Prime Minister of Russia. He was only distantly related to the latter.

- ^ 'Memoir', p. 37.

- ^ 'Memoir', p. 43.

- ^ 'Memoir', pp. 46–47.

- ^ a b 'Memoir', p. 61.

- ^ 'Memoir', p.32.

- ^ 'Memoir', p.33. The arrangement was that he was too lecture one term in Edinburgh and a second in Glasgow.

- ^ Who was Who entry, p.1239

- ^ These awards are listed in his Who was Who entry, p.1239

- 1873 births

- 1934 deaths

- People educated at George Watson's College

- Scientists from Edinburgh

- Scottish scholars and academics

- Scottish biographers

- Scottish non-fiction writers

- Diplomats from Edinburgh

- Scottish Christian theologians

- Alumni of the University of Edinburgh

- Members of the Royal Company of Archers

- Academics from Edinburgh