Israeli citizenship law

| Citizenship Law, 5712-1952 חוק האזרחות, התשי"ב-1952 | |

|---|---|

| |

| Knesset | |

| Citation | SH 95 146 |

| Territorial extent | Israel |

| Enacted by | 2nd Knesset |

| Enacted | 1 April 1952[1] |

| Commenced | 14 July 1952[1] |

| Legislative history | |

| First reading | 20 November 1951 |

| Second reading | 25–26 March 1952 |

| Third reading | 1 April 1952[2] |

| Repeals | |

| Palestinian Citizenship Order 1925 | |

| Status: Amended | |

Israeli citizenship law details the conditions by which a person holds citizenship of Israel. The two primary pieces of legislation governing these requirements are the 1950 Law of Return and 1952 Citizenship Law.

Every Jew has the unrestricted right to immigrate to Israel and become an Israeli citizen. Individuals born within the country receive citizenship at birth if at least one parent is a citizen. Non-Jewish foreigners may naturalize after living there for at least three years while holding permanent residency and demonstrating proficiency in the Hebrew language. Naturalizing non-Jews are additionally required to renounce their previous nationalities, while Jewish immigrants are not subject to this requirement.

The territory of modern Israel was formerly administered by the British Empire as part of a League of Nations mandate for Palestine and local residents were British protected persons. The dissolution of the mandate in 1948 and subsequent conflict created a set of complex citizenship circumstances for the non-Jewish inhabitants of the region that continue to be unresolved. While pre-1948 Palestinian Arab residents of the former mandate and their descendants who remained living in Israel were granted Israeli citizenship in 1980, those resident in the West Bank and Gaza Strip are largely considered stateless.

Terminology

The distinction between the meaning of the terms citizenship and nationality is not always clear in the English language and differs by country. Generally, nationality refers a person's legal belonging to a state and is the common term used in international treaties when referring to members of a state; citizenship refers to the set of rights and duties a person has in that nation.[3]

In the Israeli context, nationality is not linked to a person's origin from a particular territory but is more broadly defined. Although the term may be used in other countries to indicate a person's ethnic group, the meaning in Israeli law is particularly expansive by including any person practicing Judaism and their descendants.[4] Members of the Jewish nationality form the core part of Israel's citizenry,[5] while the Supreme Court of Israel has ruled that an Israeli nationality does not exist.[5][6] Legislation has defined Israel as the nation state of the Jewish people since 2018.[7]

History

National status under British mandate

The region of Palestine was conquered by the Ottoman Empire in 1516. Accordingly, Ottoman nationality law applied to the area. Palestine was governed by the Ottomans for four centuries until British occupation in 1917 during the First World War.[8] The area nominally remained an Ottoman territory following the conclusion of the war until the United Kingdom obtained a League of Nations mandate for the region in 1922. Similarly, local residents ostensibly continued their status as Ottoman subjects, although British authorities began issuing provisional certificates of Palestinian nationality shortly after the start of occupation.[9] The terms of the mandate allowed Britain to exclude its application on certain parts of the region; this exclusion was exercised on the territory east of the Jordan River,[10] where the Emirate of Transjordan was established.[11]

The Treaty of Lausanne established the basis for separate nationalities in Mandatory Palestine and all other territories ceded by the Ottoman Empire. The Palestinian Citizenship Order 1925 confirmed the transition from Ottoman/Turkish to Palestinian citizenship in local legislation;[12] all Ottoman/Turkish subjects who were ordinarily resident in Palestine on 1 August 1925 became Palestinian citizens on that date.[13] Turkish nationals originating from Mandate territory but habitually resident elsewhere on 6 August 1924 had a right to choose Palestinian citizenship, but this required an application within two years of the treaty's enforcement and approval by the Mandatory government.[14] This right of option was later extended until 24 July 1945.[13] A 1931 amendment automatically extended Palestinian citizenship to Turkish nationals who had been living in Palestine on 6 August 1924 but became resident abroad before 1 August 1925, unless they voluntarily acquired another nationality before 23 July 1931.[13]

Legitimate children of a Palestinian father automatically held Palestinian citizenship. Any person born outside these conditions who held no other nationality and was otherwise stateless at birth also automatically acquired citizenship. Foreigners could obtain Palestinian citizenship through naturalization after residing in the territory for at least two of the three years preceding an application, fulfilling a language requirement (in English, Hebrew, or Arabic), affirming their intention to permanently reside in Mandate territory, and satisfying a good character requirement.[15]

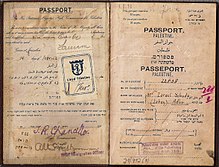

Despite Britain's sovereignty over Palestinian territory, domestic law in the United Kingdom treated the mandate as foreign territory. Palestinian citizens were treated as British protected persons, rather than British subjects, meaning that they were aliens in the UK but could be issued Mandatory Palestine passports by British authorities. Protected persons could not travel to the UK without first requesting permission, but were afforded the same consular protection as British subjects when travelling outside the British Empire.[16] This arrangement continued until termination of the British mandate on 14 May 1948,[17] the same date on which the State of Israel was established.[18]

Post-1948 transition

For the first four years after its establishment, Israel had no citizenship law and technically had no citizens.[1] International law typically assumes the continued operation of laws of a predecessor state in the event of a succession of states.[19] However, despite Israel's status as the successor state to Mandatory Palestine,[20] Israeli courts during this time offered conflicting opinions on the continuing validity of Palestinian citizenship legislation enacted during the British mandate.[21] While almost all courts held that Palestinian citizenship had ceased to exist at the end of the mandate in 1948 without a replacement status, there was one case in which a judge ruled that all residents of Palestine at the time of Israel's establishment were automatically Israeli nationals.[19] The Supreme Court settled this issue in 1952, ruling that Palestinian citizens of the British mandate had not automatically become Israeli.[22]

Israeli citizenship policy is centered on two early pieces of legislation: the 1950 Law of Return and 1952 Citizenship Law.[23] The Law of Return grants every Jew the right to migrate to and settle in Israel, reinforcing the central Zionist tenet of the return of all Jews to their traditional homeland.[24] The Citizenship Law details the requirements for Israeli citizenship, dependent on an individual's religious affiliation,[25] and explicitly repeals all prior British-enacted legislation concerning Palestinian nationality.[26]

Status of Palestinian Arabs

Following its victory in the 1948 Arab–Israeli War, Israel controlled the majority of former Mandatory Palestine, including much of the land assigned for an Arab state under the United Nations Partition Plan for Palestine. The West Bank was annexed by Jordan while the Gaza Strip fell under the administration of Egypt.[27] The UNRWA estimated that 720,000 Palestinian Arabs were displaced during the war,[28] with only 170,000 remaining in Israel after its establishment.[29] Despite international support for the return of displaced Palestinians after conclusion of the war, the Israeli government was unwilling to allow what it regarded as a hostile population into its borders and barred them from returning. The administration justified this prohibition as a defensive measure against continued Arab incursions into Israeli territory as well as to official rhetoric from neighboring Arab states that expressed their desire to eliminate Israel, which views a Palestinian right of return to any part of its territory as an existential threat to the nation's security.[30]

Jewish residents at the time of Israel's establishment were granted Israeli citizenship based on return, but non-Jewish Palestinians were subject to strict residency requirements for claiming that status. They could only acquire citizenship based on their residence in 1952 if they were nationals of the British mandate before 1948, had registered as Israeli residents since February 1949 and remained registered, and had not left the country before claiming citizenship.[31] These requirements were intended to systemically exclude Arabs from participation in the new state.[28] About 90 percent of the Arab population that remained in Israel were barred from citizenship under the residence requirements and held no nationality.[29]

Palestinians who managed to return to their homes in Israel after the war did not satisfy the conditions for citizenship under the 1952 law. This class of residents continued living in Israel but held no citizenship or residence status. A 1960 Supreme Court ruling partially addressed this by allowing a looser interpretation of the residential requirements; individuals who had permission to temporarily leave Israel during or shortly after the conflict qualified for citizenship, despite their gap in residence. The Knesset amended the Citizenship Law in 1980 to fully resolve statelessness for this group of residents; all Arab residents who had been living in Israel before 1948 were granted citizenship regardless of their eligibility under the 1952 residence requirements, along with their children.[32]

Conversely, Palestinians who had fled to neighboring countries were not granted citizenship there and remained stateless except those who resettled in Jordan.[33] After Israel took control of the West Bank following the 1967 Six-Day War,[34] Jordan maintained its sovereignty claim over the area until 1988, when it renounced this claim and unilaterally severed all links to the region. Palestinians living in the West Bank lost Jordanian nationality while those residing in the rest of Jordan maintained that status.[33]

Following agreement on the Oslo Accords in the 1990s, Palestinians have been eligible for Palestinian Authority passports.[35] However, the terms of these accords did not result in the creation of a definitive Palestinian state, nor has any legislation regulating Palestinian citizenship been enacted by the Palestinian Legislative Council.[36] Palestinians may be considered stateless by other countries as their status is not tied to a sovereign state, although recognition of their statelessness varies by government.[37]

Annexed territories

Israel captured East Jerusalem in 1967 during the Six-Day War, incorporating it into the municipal administration of West Jerusalem. Arab residents of East Jerusalem did not automatically become Israeli citizens but were given permanent resident status. Although they may apply for naturalization, few have done so due to the Hebrew language requirement and resistance to acknowledging Israeli control of Jerusalem.[38] After passage of the 1980 Jerusalem Law, the Supreme Court has considered the territory as having been annexed by Israel.[39] About 19,000 residents, representing five percent of the East Jerusalem Palestinian population, held Israeli citizenship in 2022.[40]

Similarly, the Golan Heights was incorporated into Israel proper in 1981 and Druze residents were granted permanent resident status. Although eligible for naturalization as Israeli citizens, the Golan Druze have largely retained Syrian nationality.[41] About 4,300 of the 21,000 Druze living in the area held Israeli citizenship in 2022.[42] Prior to Syrian independence, this territory was part of the Mandate for Syria and the Lebanon assigned to France.[43] The extension of Israeli law and effective annexation of both East Jerusalem and the Golan Heights are regarded by the United Nations Security Council and United Nations General Assembly as illegal acts of aggression.[44]

Qualification under right of return

Apostate and irreligious Jews

Although the Law of Return gave every Jew the right to immigrate to Israel, the original text and all other legislation up to that point lacked a clear definition for who was considered a Jew.[45] Government and religious authorities continually disagreed over the meaning of the word and its application to that law, with some organizations considering the Jewish religion and nationality to be the same concept. One of these bodies was the National Religious Party, which led the Ministry of Interior until 1970. Accordingly, the Law of Return during this period was strictly interpreted under halakha (Jewish religious law); a Jew was defined as anyone born to a Jewish mother. While Israel is not a theocracy, the Jewish religion has a central role in Israeli politics because the main purpose of the country's establishment was to create an independent Jewish state.[46]

This absence of legal clarity was tested in the 1962 Supreme Court case Rufeisen v. Minister of the Interior in which Oswald Rufeisen, a Polish Jew who had converted to Catholicism, was ruled to have no longer met the criterion of being a Jew on his religious conversion.[47] Converting to any other faith is considered to be a deliberate act of dissociation from the Jewish people. The Supreme Court elaborated on this in the 1969 case Shalit v. Minister of the Interior, when it ruled that children of non-practicing Jews would be considered Jews. Unlike Rufeisen, the children took no action that could be considered dissociating. However, this ruling created a separation between the Jewish religion and the legal interpretation of membership in the Jewish people that required legislative clarification.[48]

The Law of Return was amended in 1970 to provide a more detailed explanation of who qualifies: a Jew means any person born to a Jewish mother, or someone who has converted to Judaism and is not an adherent of another religion. The amendment extended the right of return to Israel to include children, grandchildren, and a spouse of a Jew, as well as spouses of their children and grandchildren.[49] This entitlement was given despite the fact that not all applicable persons would be considered Jews under halakha.[50]

The Citizenship Law was amended in 1971 to allow any Jew who formally expresses their desire to migrate to Israel to immediately become an Israeli citizen, without any requirement to enter Israeli territory. This change was made to facilitate emigration of Jews from the Soviet Union, who were routinely denied exit visas,[51] especially after the 1967 Six-Day War.[52] Migration from the Soviet Union remained at low levels until exit restrictions were relaxed in the late 1980s.[25]

Most emigrating Soviet Jews initially departed for the United States, with some making their way to Germany.[53][54] However, these countries soon imposed restrictions on Jews who could immigrate from the Soviet Union at the request of the Israeli government, which intended to redirect the flow of migrants to Israel itself. The US began enforcing an entry quota of 50,000 people in 1990 while Germany restricted admission in 1991 only to Jews who could prove German ancestry. The number of Soviet Jews emigrating to Israel increased sharply from just 2,250 in 1988 to over 200,000 in 1990[55] and remained at high levels following the dissolution of the Soviet Union in 1991 and subsequent 1998 Russian financial crisis. About 940,000 Jews from the former Soviet Union departed for Israel between 1989 and 2002.[56] Most of this wave of migrants were nonpracticing and secular Jews; a significant portion were not considered Jewish under halakha, but qualified for immigration based on the Law of Return.[57]

Recognition of non-Orthodox Jews and exceptional cases

The definition of a Jew in the 1970 Law of Return amendment does not explain the meaning of "conversion" and has been interpreted to allow for adherents of any Jewish movement to qualify for right of return.[58] The Chief Rabbinate operates under an Orthodox interpretation of halakha and is the authoritative institution for religious matters within Israel, which has led to disputes over whether converts into non-Orthodox movements of Judaism should be recognized as Jews.[59] Foreigners who convert to Conservative or Reform Judaism within the country have been entitled to citizenship under the Law of Return since 2021.[60] Both the Chief Rabbinate and Supreme Court consider followers of Messianic Judaism as Christians and specifically bar them from right of return,[61] unless they otherwise have sufficient Jewish descent.[62]

Ethiopian Jews, also known as Beta Israel, lived as an isolated community away from mainstream Judaism since at least the Early Middle Ages prior to their contact with the outside world in the 19th century. Over the course of their prolonged separation, this population developed a number of religious practices heavily influenced by Coptic Christianity differing from those of other Jews.[63] Their status as Jews was disputed until the Chief Rabbinate confirmed its recognition of this group as Jews in 1973 and declared its support for their immigration to Israel.[64] Following Ethiopia's communist revolution and the subsequent outbreak of civil war, the Israeli government resettled 45,000 people, nearly the entire Ethiopian Jewish population.[65]

Migrating with the Beta Israel were the Falash Mura, Jews who converted to Christianity for ease of integration with Ethiopian society but largely remained associated with the Ethiopian Jewish community. A ministerial decision in 1992 ruled this community ineligible for right of return, but some migrants were allowed to immigrate to Israel for family reunification.[66] Subsequent government decisions have allowed more Falash Mura to migrate, though they are required to convert to Judaism before receiving citizenship. About 33,000 members of this community entered Israel from 1993 to 2013.[59]

Samaritans are descendants of the ancient Israelites who follow Samaritanism, a religion closely related to Judaism,[67][68] and hold an exceptional right of return without the agreement of the Chief Rabbinate.[69] In 1949, the Foreign Minister Moshe Sharett declared Samaritans eligible for Israeli citizenship under the Law of Return, reasoning that their Hebrew heritage qualified them for recognition as Jews. Although the decision was implemented as official policy, no legislation was ever enacted on the issue. Consequently, when the Chief Rabbinate reviewed a case in 1985 on whether Samaritan women could marry Jewish men (Jews in Israel are only permitted to marry other Jews) and concluded that Samaritans were required to first convert to Judaism, the Ministry of Interior revoked Samaritan entitlement to the right of return using the rabbinical ruling as justification. The Supreme Court ruled on the matter in 1994, restoring the original policy and further extending Samaritan eligibility for citizenship to members of the group who reside in the West Bank.[70] The total population of this community is about 700 people who live exclusively in either Holon or Mount Gerizim.[71]

Acquisition and loss of citizenship

Entitlement by birth, descent, or adoption

Individuals born in Israel receive citizenship at birth if at least one parent is an Israeli citizen. Children born overseas are citizens by descent if either parent is a citizen, limited to the first generation born abroad.[25] Those born abroad in the second generation who are not otherwise eligible under the Law of Return may apply for a grant of citizenship, subject to discretionary approval by the government.[72] Adopted children are automatically granted citizenship, regardless of their religious status.[73] Individuals born in Israel who are between the ages of 18 and 21 and have never held any nationality are entitled to citizenship, provided they have been continuously resident for the five years immediately preceding their application.[74]

Voluntary acquisition

Any Jew who immigrates to Israel as an oleh (Jewish immigrant) under the Law of Return automatically becomes an Israeli citizen.[75] In this context, a Jew means a person born to a Jewish mother, or someone who has converted to Judaism and does not adhere to another religion. This right to citizenship extends to any children or grandchildren of a Jew, as well as the spouse of a Jew, or the spouse of a child or grandchild of a Jew. A Jew who voluntarily converts to another religion forfeits their right to claim citizenship under this provision.[76] At the end of 2020, 21 percent of the total Jewish population in Israel was born overseas.[77]

Foreigners may naturalize as Israeli citizens after residing in Israel for at least three of the previous five years while holding permanent residency. Candidates must be physically present in the country at the time of application, be able to demonstrate knowledge of the Hebrew language, have the intention of permanently settling in Israel, and renounce any foreign nationalities.[78] Although Arabic was previously an official language and has a special recognized status,[79] there is no similar knowledge stipulation for it as part of the naturalization process.[80] All of these requirements may be partially or completely waived for a candidate if they: served in the Israel Defense Forces or suffered the loss of a child during their military service period, are a minor child of a naturalized parent or Israeli resident, or made extraordinary contributions to Israel.[81] Successful applicants are required to swear an oath of allegiance to the State of Israel.[78]

Dual/multiple citizenship is explicitly allowed for an oleh who becomes Israeli by right of return. This is to encourage the overseas Jewish diaspora to migrate to Israel without forcing them to lose their previous national statuses. By contrast, naturalization candidates are required to renounce their original nationalities to obtain citizenship. Persons opting to naturalize are typically individuals who migrate to Israel for employment or family reasons, or are permanent residents of East Jerusalem and the Golan Heights.[82]

Relinquishment and deprivation

Israeli citizenship can be voluntarily relinquished by a declaration of renunciation, provided that the declarant is living overseas, already possesses another nationality, and has no military service obligations.[83] Returnees living in Israel who obtained Israeli citizenship may voluntarily renounce that status if continuing to hold it would cause their loss of another country's nationality.[84] Between 2003 and 2015, there were 8,308 people who renounced their Israeli citizenship. While some former citizens renounce their citizenship because of their intention to permanently settle overseas and not return to Israel, others do so as a condition of obtaining foreign nationality in their country of residence.[85]

Citizenship may be involuntarily removed from individuals who fraudulently acquired it or from those who willfully perform an act that constitutes a breach of loyalty to the state.[86] The Minister of Interior may revoke citizenship from a person who obtained status based on false information within three years of that person having become an Israeli citizen. For persons who fraudulently acquired citizenship more than three years earlier, the Minister must request the Administrative Court to revoke citizenship.[87] Revocation on the basis of disloyalty has only occurred on three occasions since 1948; twice in 2002 and once in 2017.[86] Israeli citizenship may also be revoked from citizens who illegally travel to countries officially declared as enemy states (Syria, Lebanon, Iraq, and Iran)[88] or if they obtain nationality from one of those countries.[89]

Spousal rights

Non-Jewish spouses have right of return if they immigrate to Israel at the same time as their Jewish spouses;[90] same-sex spouses of Jews have been eligible for this since 2014.[91] Otherwise, they are granted temporary residence permits gradually replaced by less restrictive conditions of stay over a period of 4.5 years until they become eligible for citizenship. Until 1996, non-Jewish spouses without right of return were immediately granted permanent residency upon entry into Israel.[92] Marriages must be valid under Israeli law for the partner of a citizen to be eligible under the 4.5-year naturalization process. Common-law or same-sex partners are subject to a longer 7.5-year gradual process that grants permanent residency, after which they may apply for naturalization under the standard procedure.[93]

Male spouses under 35 and female spouses under 25 ordinarily resident in the Judea and Samaria Area (administrative division for the West Bank under Israeli law) outside Israeli settlements are prohibited from obtaining citizenship and residency until reaching the relevant age.[94] The 2003 Citizenship and Entry into Israel Law effectively discouraged further marriages between Israeli citizens and Palestinians by adding cumbersome administrative barriers that made legal cohabitation prohibitively difficult for affected couples.[95] About 12,700 Palestinians married to Israeli citizens are prevented from obtaining citizenship under these restrictions. Affected persons are only allowed to remain in Israel on temporary permits, which would lapse on the death of their spouses or if they were to fail to receive regular reapproval by the Israeli government.[96]

These restrictions were challenged as unconstitutional for violating the Basic Law: Human Dignity and Liberty on the basis that the legislation was discriminatory by disproportionally affecting Israeli citizens who were ethnically Arab. However, in its 2006 ruling upholding the legislation, the Supreme Court held that the admittance of noncitizen spouses was not a constitutional right held by Israeli citizens and that Israel was entitled to limit the entrance of any aliens into its borders. The court further ruled that Israel held a right to forbid Palestinian residents from entering the state on the basis that a state of war existed with the Palestinian National Authority (consequently making Palestinians enemy subjects).[97] The law was upheld again by the Supreme Court in 2012 and continued to be effective until its expiration in July 2021,[98][99] before reimplementation under new legislation in March 2022.[100]

Honorary citizenship

In recognition of aid provided to Jews during the Holocaust, non-Jews may be recognized as Righteous Among the Nations. These individuals may additionally be granted honorary citizenship.[101] This type of citizenship is a substantive status and gives its holders all the rights and privileges that other Israeli citizens have. About 130 Righteous Gentiles resettled in Israel; they are entitled to permanent residency and a special pension from the state.[102]

See also

References

Citations

- ^ a b c Margalith 1953, p. 63.

- ^ "Citizenship Law, 1952" (in Hebrew). Knesset. Archived from the original on 3 March 2022. Retrieved 2 March 2022.

- ^ Kondo 2001, pp. 2–3.

- ^ Tekiner 1991, p. 49.

- ^ a b Tekiner 1991, p. 50.

- ^ Goldenberg, Tia (4 October 2013). "Supreme Court rejects 'Israeli' nationality status". The Times of Israel. Archived from the original on 13 February 2020. Retrieved 6 November 2018.

- ^ Berger, Miriam (31 July 2018). "Israel's hugely controversial "nation-state" law, explained". Vox. Archived from the original on 27 January 2022. Retrieved 2 March 2022.

- ^ Qafisheh 2010, p. 1.

- ^ Qafisheh 2010, pp. 5–6.

- ^ Qafisheh 2010, p. 3.

- ^ Frost 2022, p. 3.

- ^ Qafisheh 2010, p. 17.

- ^ a b c Survey of Palestine, Volume 1, p. 206.

- ^ Qafisheh 2010, p. 16.

- ^ Survey of Palestine, Volume 1, pp. 206–207.

- ^ Jones 1945, pp. 127–128.

- ^ Qafisheh 2010, pp. 7, 16.

- ^ Kohn 1954, p. 369.

- ^ a b Goodwin-Gill & McAdam 2007, pp. 459–460.

- ^ Masri 2015, p. 362.

- ^ Masri 2015, p. 372.

- ^ Kattan 2005, p. 84.

- ^ Harpaz & Herzog 2018, p. 1.

- ^ Harpaz & Herzog 2018, pp. 1–2.

- ^ a b c Harpaz & Herzog 2018, p. 4.

- ^ Goodwin-Gill & McAdam 2007, p. 460.

- ^ Kramer 2001, p. 984.

- ^ a b Davis 1995, p. 23.

- ^ a b Davis 1995, pp. 26–27.

- ^ Kramer 2001, pp. 984–985.

- ^ Harpaz & Herzog 2018, pp. 4–5.

- ^ Shachar 1999, pp. 250–251.

- ^ a b Masri 2015, p. 375.

- ^ Sela 2019, p. 292.

- ^ Khalil 2007, p. 35.

- ^ Khalil 2007, pp. 40–41.

- ^ "Palestinians and the search for protection as refugees and stateless persons in Europe" (PDF). European Network on Statelessness. July 2022. Archived (PDF) from the original on 11 November 2023. Retrieved 29 January 2024.

- ^ Harpaz & Herzog 2018, p. 12.

- ^ Benvenisti 2012, p. 205.

- ^ Hasson, Nir (29 May 2022). "Just 5 Percent of E. Jerusalem Palestinians Have Received Israeli Citizenship Since 1967". Haaretz. Archived from the original on 11 January 2023. Retrieved 18 October 2023.

- ^ Harpaz & Herzog 2018, pp. 11–12.

- ^ Amun, Fadi (3 September 2022). "As ties to Syria fade, Golan Druze increasingly turning to Israel for citizenship". The Times of Israel. Archived from the original on 5 July 2023. Retrieved 18 October 2023.

- ^ Kattan 2019, p. 83.

- ^ Benvenisti 2012, pp. 203–205.

- ^ Savir 1963, pp. 123–124.

- ^ Richmond 1993, pp. 101–103.

- ^ Savir 1963, p. 128.

- ^ Richmond 1993, pp. 106–109.

- ^ Perez 2011, p. 61.

- ^ Harpaz & Herzog 2018, pp. 3–4.

- ^ Quigley 1991, pp. 388–389.

- ^ Stern, Sol (16 April 1972). "The Russian Jews Wonder Whether Israel Is Really Ready for Them". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 1 October 2021. Retrieved 1 October 2021.

- ^ Dietz, Lebok & Polian 2002, p. 29.

- ^ Tolts 2020, p. 323.

- ^ Quigley 1991, pp. 389–391.

- ^ Tolts 2003, p. 71.

- ^ Emmons 1997, p. 344.

- ^ Richmond 1993, pp. 110–112.

- ^ a b Harpaz & Herzog 2018, p. 16.

- ^ Kingsley, Patrick (1 March 2021). "Israeli Court Says Converts to Non-Orthodox Judaism Can Claim Citizenship". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 18 October 2021. Retrieved 18 October 2021.

- ^ "Israeli Court Rules Jews for Jesus Cannot Automatically Be Citizens". The New York Times. Associated Press. 27 December 1989. Archived from the original on 19 July 2021. Retrieved 2 October 2021.

- ^ Zieve, Tamara (16 December 2017). "Will Israel ever accept Messianic Jews?". The Jerusalem Post. Archived from the original on 2 October 2021. Retrieved 2 October 2021.

- ^ Weil 1997, pp. 397–399.

- ^ Weil 1997, pp. 400–401.

- ^ Kaplan & Rosen 1994, pp. 62–66.

- ^ Kaplan & Rosen 1994, pp. 66–68.

- ^ Schreiber 2014, pp. 1–2.

- ^ Kingsley, Patrick; Sobelman, Gabby (22 August 2021). "The World's Last Samaritans, Straddling the Israeli-Palestinian Divide". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 22 October 2023. Retrieved 28 October 2023.

- ^ Schreiber 2014, p. 62.

- ^ Schreiber 2014, pp. 57–62.

- ^ Schreiber 2014, p. 2.

- ^ "נוהל טיפול בהענקת אזרחות לקטין לפי סעיף 9(א)(2)" [Procedure for granting citizenship to a minor under Article 9(a)(2)] (PDF) (in Hebrew). Population and Immigration Authority. 1 December 2019. Archived (PDF) from the original on 12 November 2022. Retrieved 16 October 2023.

- ^ Harpaz & Herzog 2018, pp. 5–6.

- ^ Kassim 2000, p. 206.

- ^ Harpaz & Herzog 2018, pp. 2, 4.

- ^ Harpaz & Herzog 2018, p. 3.

- ^ Jews, By Continent of Origin, Continent of Birth and Period of Immigration (PDF). Statistical Abstract of Israel 2020 (Report). Central Bureau of Statistics. 31 August 2021. Archived (PDF) from the original on 28 October 2021. Retrieved 27 October 2021.

- ^ a b Herzog 2017, pp. 61–62.

- ^ "Israel Passes 'National Home' Law, Drawing Ire of Arabs". The New York Times. 18 July 2018. Archived from the original on 24 December 2018. Retrieved 30 September 2021.

- ^ Amara 1999, p. 90.

- ^ Shapira 2017, pp. 127–128.

- ^ Harpaz & Herzog 2018, pp. 9–10.

- ^ "Give up (renounce) Israeli citizenship – for Israelis living abroad". Government of Israel. Archived from the original on 1 November 2020. Retrieved 29 September 2021.

- ^ "Give up (renounce) Israeli citizenship in order to keep your foreign citizenship". Government of Israel. Archived from the original on 5 October 2021. Retrieved 29 September 2021.

- ^ Eichner, Itamar (23 June 2016). "8,308 Israelis renounced citizenship over past 12 years". Ynet. Archived from the original on 7 April 2019. Retrieved 29 September 2021.

- ^ a b Harpaz & Herzog 2018, p. 6.

- ^ Levush, Ruth (23 March 2017). "Israel: Amendment Authorizing Revocation of Israeli Nationality Passed". Library of Congress. Archived from the original on 30 September 2021. Retrieved 2 April 2018.

- ^ Herzog 2010, p. 57.

- ^ Herzog 2010, pp. 62–63.

- ^ Kaplan 2015, pp. 1090–1091.

- ^ Sharon, Jeremy (12 August 2014). "Non-Jewish partners in gay marriage are now entitled to make aliya". The Jerusalem Post. Archived from the original on 24 October 2021. Retrieved 27 October 2021.

- ^ Shapira 2017, p. 131.

- ^ Shapira 2017, p. 132.

- ^ Carmi 2007, pp. 27, 32.

- ^ Nikfar 2005, p. 2.

- ^ Keller-Lynn, Carrie (6 March 2023). "Knesset extends law banning Palestinian family unification for another year". The Times of Israel. Archived from the original on 6 June 2023. Retrieved 16 October 2023.

- ^ Carmi 2007, pp. 26, 33–35.

- ^ Boxerman, Aaron (6 July 2021). "With ban on Palestinian family unification expiring, what happens next?". The Times of Israel. Archived from the original on 4 October 2021. Retrieved 4 October 2021.

- ^ Kershner, Isabel (6 July 2021). "Israel's New Government Fails to Extend Contentious Citizenship Law". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 6 August 2021. Retrieved 4 October 2021.

- ^ Chacar, Henriette (10 March 2022). Oatis, Jonathan (ed.). "Israel's Knesset passes law barring Palestinian spouses". Reuters. Archived from the original on 11 March 2022. Retrieved 11 March 2022.

- ^ "Raoul Wallenberg Is Granted Honorary Israeli Citizenship". The New York Times. Reuters. 17 January 1986. Archived from the original on 7 July 2022. Retrieved 26 October 2023.

- ^ Jeffay, Nathan (6 October 2011). "'Righteous' Moved to Israel After Saving Jews in Holocaust". The Forward. Archived from the original on 21 May 2022. Retrieved 26 October 2023.

General sources

- Amara, Muhammad (1999). Politics and Sociolinguistic Reflexes: Palestinian Border Villages. John Benjamins Publishing Company. ISBN 978-9-02-724128-3.

- Benvenisti, Eyal (2012). The International Law of Occupation (2nd ed.). Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-958889-3.

- Carmi, Na'ama (2007). "The Nationality and Entry into Israel Case before the Supreme Court of Israel". Israel Studies Forum. 22 (1). Berghahn Books: 26–53. JSTOR 41804964.

- Davis, Uri (1995). "Jinsiyya Versus Muwatana: The Question of Citizenship and the State in the Middle East: The Cases of Israel, Jordan and Palestine". Arab Studies Quarterly. 17 (1/2). Pluto Journals: 19–50. JSTOR 41858111.

- Dietz, Barbara; Lebok, Uwe; Polian, Pavel (2002). "The Jewish Emigration from the Former Soviet Union to Germany". International Migration. 40 (2). International Organization for Migration: 29–48. doi:10.1111/1468-2435.00189 – via Wiley.

- Emmons, Shelese (1997). "Russian Jewish Immigration and its Effect on the State of Israel". Indiana Journal of Global Legal Studies. 5 (1). Indiana University Press: 341–355. Archived from the original on 5 October 2021. Retrieved 5 October 2021.

- Frost, Lillian (February 2022). Report on Citizenship Law: Jordan (Report). European University Institute. hdl:1814/74189.

- Goodwin-Gill, Guy S.; McAdam, Jane (2007). The Refugee in International Law (3rd ed.). Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-928130-5.

- Government of Mandatory Palestine (1946). Survey of Palestine (PDF) (Report). Vol. 1. Government Printer, Palestine. Archived (PDF) from the original on 13 May 2021. Retrieved 1 October 2021 – via Berman Jewish Policy Archive.

- Harpaz, Yossi; Herzog, Ben (June 2018). Report on Citizenship Law: Israel (Report). European University Institute. hdl:1814/56024.

- Herzog, Ben (2017). "The construction of Israeli Citizenship Law: Intertwining political philosophies". Journal of Israeli History. 36 (1). Taylor & Francis: 47–70. doi:10.1080/13531042.2017.1317668. S2CID 152105861.

- Herzog, Ben (2010). "The Revocation of Citizenship in Israel". Israel Studies Forum. 25 (1). Berghahn Books: 57–72. JSTOR 41805054.

- Jones, J. Mervyn (1945). "Who are British Protected Persons". The British Yearbook of International Law. 22. Oxford University Press: 122–145. Archived from the original on 23 October 2021. Retrieved 20 October 2021 – via HeinOnline.

- Kaplan, Steven; Rosen, Chaim (1994). "Ethiopian Jews in Israel". The American Jewish Year Book. 94. American Jewish Committee: 59–101. JSTOR 23605644.

- Kaplan, Yehiel S. (2015). "Immigration Policy of Israel: The Unique Perspective of a Jewish State". Touro Law Review. 31 (4). Touro Law Center: 1089–1135. Archived from the original on 2 October 2021. Retrieved 2 October 2021.

- Kassim, Anis F. (2000). "The Palestinians: From Hyphenated to Integrated Citizenship". In Butenschøn, Nils A.; Davis, Uri; Hassassian, Manuel (eds.). Citizenship and the State in the Middle East: Approaches and Applications. Syracuse University Press. pp. 201–224. ISBN 978-0-81-562829-3.

- Kattan, Victor (2005). "The Nationality of Denationalized Palestinians". Nordic Journal of International Law. 74. Brill: 67–102. doi:10.1163/1571810054301004. SSRN 993452.

- Kattan, Victor (2019). "U.S. Recognition of Golan Heights Annexation: Testament to Our Times". Journal of Palestine Studies. 48 (3). Taylor & Francis: 79–85. doi:10.1525/jps.2019.48.3.79. JSTOR 26873217.

- Khalil, Asem (2007). Palestinian Nationality and Citizenship: Current Challenges and Future Perspectives (Report). European University Institute. hdl:1814/8162.

- Kohn, Leo (April 1954). "The Constitution of Israel". The Journal of Educational Sociology. 27 (8). American Sociological Association: 369–379. doi:10.2307/2263817. JSTOR 2263817.

- Kondo, Atsushi, ed. (2001). Citizenship in a Global World. Palgrave Macmillan. doi:10.1057/9780333993880. ISBN 978-0-333-80266-3.

- Kramer, Tanya (2001). "The Controversy of a Palestinian Right of Return to Israel". Arizona Journal of International and Comparative Law. 18 (3). James E. Rogers College of Law: 979–1016. Archived from the original on 29 January 2024. Retrieved 30 November 2023 – via HeinOnline.

- Margalith, Haim (1953). "Enactment of a Nationality Law in Israel". American Journal of Comparative Law. 2 (1). Oxford University Press: 63–66. doi:10.2307/837997. JSTOR 837997.

- Masri, Mazen (2015). "The Implications of the Acquisition of a New Nationality for the Right of Return of Palestinian Refugees". Asian Journal of International Law. 5 (2). Cambridge University Press: 356–386. doi:10.1017/S2044251314000241.

- Nikfar, Bethany M. (2005). "Families Divided: An Analysis of Israel's Citizenship and Entry into Israel Law". Northwestern Journal of International Human Rights. 3 (1). Northwestern University. Archived from the original on 24 January 2021. Retrieved 4 October 2021.

- Perez, Nahshon (February 2011). "Israel's Law of Return: A Qualified Justification". Modern Judaism. 31 (1). Oxford University Press: 59–84. doi:10.1093/mj/kjq032. JSTOR 41262403.

- Qafisheh, Mutaz M. (2010). "Genesis of Citizenship in Palestine and Israel". Bulletin du Centre de recherche français à Jérusalem. 21. Archived from the original on 30 September 2021. Retrieved 30 September 2021.

- Quigley, John (1991). "Soviet Immigration To The West Bank: Is It Legal?". Georgia Journal of International and Comparative Law. 21 (3). University of Georgia: 387–413. Archived from the original on 1 October 2021. Retrieved 1 October 2021.

- Richmond, Nancy C. (1 September 1993). "Israel's Law of Return: Analysis of Its Evolution and Present Application". Penn State International Law Review. 12 (1). Pennsylvania State University: 95–133. Archived from the original on 27 September 2020. Retrieved 1 October 2021.

- Savir, Yehuda (1963). "The Definition of a Jew under Israel's Law of Return". Southwestern Law Journal. 17 (1). Southern Methodist University: 123–133. Archived from the original on 30 September 2021. Retrieved 30 September 2021 – via HeinOnline.

- Schreiber, Monica (2014). The Comfort of Kin: Samaritan Community, Kinship, and Marriage. Brill. doi:10.1163/9789004274259. ISBN 978-90-04-27425-9.

- Sela, Avraham (2019). "The West Bank Under Jordan". In Kumaraswamy, P. R. (ed.). The Palgrave Handbook of the Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan. Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 277–294. doi:10.1007/978-981-13-9166-8_17. ISBN 978-981-13-9166-8.

- Shachar, Ayelet (1999). "Whose Republic: Citizenship and Membership in the Israeli Polity". Georgetown Immigration Law Journal. 13 (2). Georgetown University: 233–272. Archived from the original on 2 October 2021. Retrieved 2 October 2021 – via HeinOnline.

- Shapira, Assaf (2017). "Israel's Citizenship Policy towards Family Immigrants: Developments and Implications". Journal of Israeli History. 36 (2). Taylor & Francis: 125–147. doi:10.1080/13531042.2018.1545676. S2CID 165436471.

- Tekiner, Roselle (1991). "Race and the Issue of National Identity in Israel". International Journal of Middle East Studies. 23 (1). Cambridge University Press: 39–55. doi:10.1017/S0020743800034541. JSTOR 163931. S2CID 163043582.

- Tolts, Mark (2003). "Mass Aliyah and Jewish emigration from Russia: Dynamics and factors". East European Jewish Affairs. 33 (2). Taylor & Francis: 71–96. doi:10.1080/13501670308578002. S2CID 161362436.

- Tolts, Mark (2020). "A Half Century of Jewish Emigration from the Former Soviet Union". In Denisenko, Mikhail; Strozza, Salvatore; Light, Matthew (eds.). Migration from the Newly Independent States: 25 Years After the Collapse of the USSR. Societies and Political Orders in Transition. Springer. pp. 323–344. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-36075-7_15. ISBN 978-3-030-36074-0.

- Weil, Shalva (1997). "Religion, Blood and the Equality of Rights: The Case of Ethiopian Jews in Israel". International Journal on Minority and Group Rights. 4 (3/4). Brill: 397–412. doi:10.1163/15718119620907256. JSTOR 24674566.