Israel the Grammarian

Israel the Grammarian | |

|---|---|

| Born | c. 895 |

| Died | c. 969 |

| Other names | Israel Scot Israel of Trier |

| Academic background | |

| Influences | Eriugena |

| Academic work | |

| Main interests | Latin, grammar, poetry, linguistics, theology |

Israel the Grammarian[a] (c. 895 – c. 965) was one of the leading European scholars of the mid-tenth century. In the 930s, he was at the court of King Æthelstan of England (r. 924–39). After Æthelstan's death, Israel successfully sought the patronage of Archbishop Rotbert of Trier and became tutor to Bruno, later the Archbishop of Cologne. In the late 940s Israel is recorded as a bishop, and at the end of his life he was a monk at the Benedictine monastery of Saint-Maximin in Trier.

Israel was an accomplished poet, a disciple of the ninth-century Irish philosopher John Scottus Eriugena and one of the few Western scholars of his time to understand Greek. He wrote theological and grammatical tracts, and commentaries on the works of other philosophers and theologians.

Background

[edit]

The reign of Charlemagne saw a revival in learning in Europe from the late eighth century, known as the Carolingian Renaissance. The Carolingian Empire collapsed in the late ninth century, while the tenth is seen as a period of decline, described as the "Age of Iron" by a Frankish Council in 909. This negative picture of the period is increasingly challenged by historians; in Michael Wood's view "the first half of the tenth century saw many remarkable and formative developments that would shape European culture and history."[2] The Bible remained the primary fount of knowledge, but study of classical writers, who had previously been demonised as pagans, became increasingly acceptable.[3]

When Alfred the Great became King of Wessex in 871, learning in southern England was at a low level, and there were no Latin scholars. He embarked on a programme of revival, bringing in scholars from Continental Europe, Wales and Mercia, and himself translated works he considered important from Latin to the vernacular. His grandson, Æthelstan, carried on the work, inviting foreign scholars such as Israel to England, and appointing a number of continental clerics as bishops. In the 930s the level of learning was still not high enough to supply enough literate English priests to fill the bishoprics. The generation educated in Æthelstan's reign, such as the future Bishop of Winchester, Æthelwold, who was educated at court, and Dunstan, who became Archbishop of Canterbury, went on to raise English learning to a high level.[4]

Early life

[edit]Very little is known about Israel's early life. Michael Lapidge dates his birth to around 900,[5] while Wood places it slightly earlier, around 890.[6] He was a disciple of Ambrose and spent time at Rome, but it is unknown who Ambrose was or whether he was Israel's tutor in Rome.[7] In Wood's view Israel was a monk at Saint-Maximin in Trier in the 930s.[6]

Tenth-century sources provide conflicting evidence on Israel's origin. Ruotger in his life of Bruno referred to Israel as Irish, whereas Flodoard in his Chronicle described him as "Britto", which may refer to Brittany, Cornwall or Wales, all three of which were Celtic speaking refuges for Britons who had fled the Anglo-Saxon invasion of England.[8] According to Lapidge: "The consensus of modern scholarship is in favour of an Irish origin, but the matter has not been properly investigated."[9] He argues that the bishop of Bangor in County Down, Dub Innse, described Israel as a "Roman scholar", and that he therefore does not appear to have recognised him as a fellow Irishman. Lapidge states that Flodoard was contemporary with Israel and may have known him, whereas Ruotger wrote after Israel's death and probably did not have first hand knowledge. Giving children Old Testament Hebrew names such as Israel was common in Celtic areas in the tenth century. Lapidge concludes that Brittany is more likely than Wales or Cornwall, as manuscripts associated with him have Breton glosses, and Æthelstan's court was a haven for Breton scholars fleeing Viking occupation of their homeland.[10]

In 2007, Wood revived the Irish theory, questioning whether Flodoard's "Israel Britto" means "Breton", and stating that Ruotger knew Israel.[11] Æthelstan's biographer, Sarah Foot, mentions Wood's view, but she rejects it, stating that Israel was not Irish and may have been a Breton.[12] Thomas Charles-Edwards, a historian of medieval Wales, thinks he may have been Welsh.[13]

Æthelstan's court

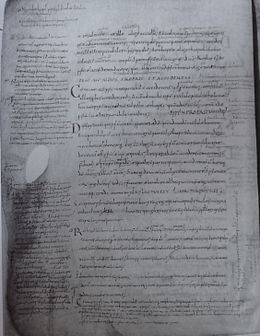

[edit]Israel's presence in England is known from a gospel book written in Ireland in about 1140, which contains a copy of a tenth-century drawing and explanation of a board game called Alea Evangelii (Gospel Game),[b] based on canon tables (concordances for parallel texts of the four gospels). According to a translation by Lapidge of a note on the manuscript:

- Here begins the Gospel Dice [or Game][c] which Dub Innse, bishop of Bangor, brought from the English king, that is from the household of Æthelstan, King of England, drawn by a certain Franco [or Frank] and by a Roman scholar, that is Israel.[17]

The twelfth-century copyist appears to have changed Dub Innse's first person note to the third person. In a later passage, he interprets "Roman scholar, that is Israel" as meaning a Roman Jew (Iudeus Romanus). This has been taken by some historians, including David Wasserstein, as showing that there was a Jewish scholar at Æthelstan's court, but Lapidge argues that this interpretation was a misunderstanding by the copyist, and his view has been generally accepted by historians.[18] Israel is thought to be Israel the Grammarian, described as a Roman scholar because of his time in the city, and the Gospel Game manuscript shows that he spent a period at Æthelstan's court. A number of manuscripts associated with Israel, including two of the four known copies of his poem De arte metrica, were written in England.[19] In Foot's view:

- Israel provides a tantalising link between the spheres of masculine camaraderie of a conventional royal court and the more rarefied, scholarly atmosphere that Æthelstan may have liked both his contemporaries and posterity to think he was keen to promote.[20]

Israel was a practitioner of the "hermeneutic style" of Latin, characterised by long, convoluted sentences and a predilection for rare words and neologisms. He probably influenced the scribe known to historians as "Æthelstan A", an early exponent of the style in charters he drafted between 928 and 935.[21] Hermeneutic Latin was to become the dominant style of the English Benedictine reform movement of the later tenth century, and Israel may have been an early mentor of one of its leaders, Æthelwold, at Æthelstan's court in the 930s.[22] The Latin texts which Israel brought to Æthelstan's court were influenced by Irish writers, and the historian Jane Stevenson sees them as contributing a Hiberno-Latin element to the hermeneutic style in England.[23]

Later career

[edit]Israel's poem De arte metrica was dedicated to Rotbert, Archbishop of Trier. It was almost certainly composed in England, and the dedication was probably a successful plea for Rotbert's patronage when Æthelstan died in 939. From about 940 Israel was the tutor of Bruno, the future Archbishop of Cologne and brother of the Holy Roman Emperor, Otto the Great. Froumund of Tegernsee described Israel as Rotbert's "shining light". In 947 Israel attended a synod at Verdun presided over by Rotbert, where he was referred to as a bishop, but without identification of his see.[24] He was famous as a schoolmaster and probably played an important role in Emperor Otto's establishment of a court school at Aachen.[25]

Tenth-century sources describe Israel as a bishop; around 950 a man with this name is identified as Bishop of Aix-en-Provence, but it is not certain that he was the same person.[26] Between 948 and 950 he may have held a bishopric in Aachen, where he debated Christian ideas about the Trinity with a Jewish intellectual called Salomon, probably the Byzantine ambassador of that name.[27] He retired to become a monk at the Benedictine monastery of Saint-Maximin in Trier, and died on 26 April in an unknown year in the late 960s or early 970s.[28]

Scholarship

[edit]Charters produced from 928 by King Æthelstan's scribe, "Æthelstan A", include unusual words almost certainly copied from the Hiberno-Irish poems Adelphus adelphe and Rubisca. The poems display a sophisticated knowledge of Greek and are described by Lapidge as "immensely difficult". It is likely that they were brought by Israel from the Continent, while Adelphus adelphe was probably, and Rubisca possibly, his work.[29][d]

Mechthild Gretsch describes Israel as "one of the most learned men in Europe",[31] and Lapidge says that he was "an accomplished grammarian and poet, and one of the few scholars of his time to have first-hand knowledge of Greek".[32] Greek scholarship was so rare in western Europe during this period that in the 870s Anastasius the Librarian was unable to find anyone competent to edit his translation of a text from Greek, and had to do it himself.[33] Israel wrote on theology and collected works of medicine.[25] In the 940s he became interested in the Irish philosopher John Scottus Eriugena, and commented on his works in a manuscript which survives in Saint Petersburg.[34] In a manuscript glossing Porphyry's Isagoge, he recommended John's Periphyseon. His redaction of a commentary on Donatus's Ars Minor was a major teaching text in the Middle Ages, and still in print in the twentieth century.[35]

Notes

[edit]- ^ Israel is called the Grammarian by most modern scholars, but Édouard Jeauneau refers to him as "Israel Scot"[1] (meaning Irish) and Michael Wood as "Israel of Trier".[2]

- ^ Alea Evangelii is a member of the hnefatafl family, which are asymmetrical board games in which two opponents have unequal forces and different goals. The historian of board games, H. J. R. Murray, describes Alea Evangelii as "a curious attempt to give a scriptural meaning to hnefatafl, which is here named alea",[14] while another historian of games, David Parlett, regards it as "a form of hnefatafl in a peculiarly inappropriate allegorical guise".[15]

- ^ "Alea" can mean lots or dice, and Lapidge translates Alea Evangelii as "Gospel Dice", but dice are not used in the game, and Parlett prefers "Gospel Game".[16]

- ^ Lapidge states that Israel probably wrote Rubisca, but other scholars prefer a date before his time.[29] Stevenson thinks it was written by an Irish scholar on the Continent in the late ninth or early tenth century.[30]

References

[edit]- ^ Lapidge 1993, p. 87 n. 1.

- ^ a b Wood 2010, p. 135.

- ^ Leonardi 1999, pp. 186–88.

- ^ Lapidge 1993, pp. 5–24; Wood 2010, p. 138; Leonardi 1999, p. 191.

- ^ Lapidge 1993, pp. 88–89.

- ^ a b Wood 2010, p. 138.

- ^ Lapidge 1993, pp. 88, 92.

- ^ Lapidge 1993, p. 90.

- ^ Lapidge 1993, pp. 87–88.

- ^ Lapidge 1993, pp. 89–92, 99–103.

- ^ Wood 2007, pp. 205–06; Wood 2010, pp. 141–42.

- ^ Foot 2011, p. 104.

- ^ Charles-Edwards 2013, p. 635.

- ^ Murray 1952, p. 61.

- ^ Parlett 1999, p. 202.

- ^ Lapidge 1993, p. 89; Parlett 1999, p. 202.

- ^ Lapidge 1993, p. 89.

- ^ Wasserstein 2002, pp. 283–88; Lapidge 1993, p. 89 n. 17; Foot 2011, p. 104.

- ^ Lapidge 1993, pp. 92–103.

- ^ Foot 2011, p. 105.

- ^ Lapidge 1993, p. 105; Gretsch 1999, pp. 314, 336; Woodman 2013, pp. 227–28.

- ^ Gretsch 1999, pp. 314–15, 336; Lapidge 1993, p. 111.

- ^ Stevenson 2002, p. 276.

- ^ Lapidge 1993, pp. 88, 103; Wood 2010, p. 159.

- ^ a b Wood 2010, p. 142.

- ^ Lapidge 1993, p. 88.

- ^ Wood 2010, p. 160.

- ^ Lapidge 1993, pp. 88–89; Wood 2010, pp. 138, 161.

- ^ a b Lapidge 2014, p. 260; Woodman 2013, pp. 227–28.

- ^ Stevenson 2002, p. 277.

- ^ Gretsch 1999, p. 314.

- ^ Lapidge 2014, p. 260.

- ^ Leonardi 1999, p. 189.

- ^ Lapidge 1993, pp. 87, 103.

- ^ Wood 2010, pp. 140, 149.

Sources

[edit]- Charles-Edwards, T. M. (2013). Wales and the Britons 350–1064. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-821731-2.

- Foot, Sarah (2011). Æthelstan: The First King of England. New Haven, Connecticut: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-12535-1.

- Gretsch, Mechthild (1999). The Intellectual Foundations of the English Benedictine Reform. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-03052-6.

- Lapidge, Michael (1993). Anglo-Latin Literature 900–1066. London, UK: The Hambledon Press. ISBN 1-85285-012-4.

- Lapidge, Michael (2014). "Israel the Grammarian". In Lapidge, Michael; Blair, John; Keynes, Simon; Scragg, Donald (eds.). The Wiley Blackwell Encyclopedia of Anglo-Saxon England (2nd ed.). Chichester, West Sussex: Wiley Blackwell. pp. 260–61. ISBN 978-0-470-65632-7.

- Leonardi, Claudio (1999). "Intellectual Life". In Reuter, Timothy (ed.). The New Cambridge Medieval History. Vol. III. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-36447-8.

- Murray, H. J. R. (1952). A History of Board-Games Other Than Chess. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-827401-7.

- Parlett, David (1999). The Oxford History of Board Games. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-212998-8.

- Stevenson, Jane (2002). "The Irish Contribution to Anglo-Latin Hermeneutic Prose". In Richter, Michael; Picard, Jean Michel (eds.). Ogma: Essays in Celtic Studies in Honour of Prionseas Ni Chathain. Dublin, Ireland: Four Courts Press. ISBN 1-85182-671-8.

- Wasserstein, David J. (2002). "The First Jew in England: 'The Game of the Evangel' and a Hiberno-Latin Contribution to Anglo-Jewish History". In Richter, Michael; Picard, Jean Michel (eds.). Ogma: Essays in Celtic Studies in Honour of Prionseas Ni Chathain. Dublin, Ireland: Four Courts Press. ISBN 1-85182-671-8.

- Wood, Michael (2007). "'Stand Strong Against the Monsters': Kingship and Learning in the Empire of King Æthelstan". In Wormald, Patrick; Nelson, Janet (eds.). Lay Intellectuals in the Carolingian World. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-83453-7.

- Wood, Michael (2010). "A Carolingian Scholar in the Court of King Æthelstan". In Rollason, David; Leyser, Conrad; Williams, Hannah (eds.). England and the Continent in the Tenth Century:Studies in Honour of Wilhelm Levison (1876-1947). Turnhout, Belgium: Brepols. ISBN 978-2-503-53208-0.

- Woodman, D. A. (December 2013). "'Æthelstan A' and the Rhetoric of Rule". Anglo-Saxon England. 42. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press: 217–248. doi:10.1017/S0263675113000112. S2CID 159948509.

Further reading

[edit]- Jeauneau, Edouard (1987). "Pour le dossier d'Israel Scot". Etudes Erigéniennes (in French). pp. 641–706.

- Jeudy, Colette (1977). "Israël le grammairien et la tradition manuscrite du commentaire de Remi d'Auxerre à l' 'Ars minor' de Donat". Studi medievali. 3 (in French) (18): 751–771.

- Ruiz Arzalluz, Iñigo (2021). "Israel el gramático y la transmisión de algunos textos escolares a la luz de un nuevo testimonio". Scriptorium (in Spanish) (75): 285–308.

- Selmer, Carl (1950). "Israel, ein unbekannter Schotte des 10. Jahrunderts". Studien und Mitteilungen zur Geschichte des Benediktiner-Ordens und seiner Zweige (in German) (62): 69–86.