History of Iraq

| History of Iraq |

|---|

|

|

|

Iraq, a country located in West Asia, largely coincides with the ancient region of Mesopotamia, often referred to as the cradle of civilization. The history of Mesopotamia extends back to the Lower Paleolithic period, with significant developments continuing through the establishment of the Caliphate in the late 7th century AD, after which the region became known as Iraq. Within its borders lies the ancient land of Sumer, which emerged between 6000 and 5000 BC during the Neolithic Ubaid period. Sumer is recognized as the world’s earliest civilization, marking the beginning of urban development, written language, and monumental architecture. Iraq's territory also includes the heartlands of the Akkadian, Neo-Sumerian, Babylonian, Neo-Assyrian, and Neo-Babylonian empires, which dominated Mesopotamia and much of the Ancient Near East during the Bronze and Iron Ages.

Iraq was a center of innovation in antiquity, producing early written languages, literary works, and significant advancements in astronomy, mathematics, law, and philosophy. This era of indigenous rule ended in 539 BC when the Neo-Babylonian Empire was conquered by the Achaemenid Empire under Cyrus the Great, who declared himself the "King of Babylon." The city of Babylon, the ancient seat of Babylonian power, became one of the key capitals of the Achaemenid Empire.

In the following centuries, the regions constituting modern Iraq came under the control of several empires, including the Greeks, Parthians, and Romans, establishing new centers like Seleucia and Ctesiphon. By the 3rd century AD, the region fell under Persian control through the Sasanian Empire, during which time Arab tribes from South Arabia migrated into Lower Mesopotamia, leading to the formation of the Sassanid-aligned Lakhmid kingdom. The Arabic name al-ʿIrāq likely originated during this period. The Sasanian Empire was eventually conquered by the Rashidun Caliphate in the 7th century, bringing Iraq under Islamic rule after the Battle of al-Qadisiyyah in 636. The city of Kufa, founded shortly thereafter, became a central hub for the Rashidun dynasty until their overthrow by the Umayyads in 661.

With the rise of the Abbasid Caliphate in the mid-8th century, Iraq became the center of Islamic rule, with Baghdad, founded in 762, serving as the capital. Baghdad flourished during the Islamic Golden Age, becoming a global center for culture, science, and intellectualism. However, the city's prosperity declined following the Buwayhid and Seljuq invasions in the 10th century and suffered further with the Mongol invasion of 1258. Iraq later came under the control of the Ottoman Empire in the 16th century, remaining under Ottoman rule until the end of World War I, after which Mandatory Iraq was established by the British Empire. Iraq gained independence in 1932 as the Kingdom of Iraq, which became a republic in 1958. The modern era has seen Iraq facing challenges, including the rule of Saddam Hussein, the 2003 invasion of Iraq, and subsequent efforts to rebuild the country amidst sectarian violence and the rise of the Islamic State. Despite these difficulties, Iraq plays a vital role in the geopolitics of the Middle East.

Prehistory

[edit]

Between 65,000 BC and 35,000 BC, northern Iraq was home to a Neanderthal culture, archaeological remains of which have been discovered at Shanidar Cave.[3] During 1957–1961, Shanidar Cave was excavated by Ralph Solecki and his team from Columbia University, uncovering nine skeletons of Neanderthal man of varying ages and states of preservation (labelled Shanidar I–IX). A tenth individual was later discovered by M. Zeder during examination of a faunal assemblage from the site at the Smithsonian Institution. The remains seemed to suggest that Neanderthals had funeral ceremonies, burying their dead with flowers (although the flowers are now thought to be a modern contaminant), and that they took care of injured and elderly individuals.

This region is also the location of a number of pre-Neolithic burials, dating from approximately 11,000 BC.[4] Since approximately 10,000 BC, Iraq, together with a large part of the Fertile Crescent, was a center of a Neolithic culture known as Pre-Pottery Neolithic A (PPNA), where agriculture and cattle breeding appeared for the first time. In Iraq, this period has been excavated at sites like M'lefaat and Nemrik 9. The following Neolithic period, PPNB, is represented by rectangular houses. At the time of the pre-pottery Neolithic, people used vessels made of stone, gypsum, and burnt lime (Vaisselle blanche). Finds of obsidian tools from Anatolia are evidence of early trade relations. Further important sites of human advancement were Jarmo (circa 7100 BC),[4] a number of sites belonging to the Halaf culture, and Tell al-'Ubaid, the type site of the Ubaid period (between 6500 BC and 3800 BC).[5]

Ancient Mesopotamia

[edit]Mesopotamia is the site of the earliest developments of the Neolithic Revolution from around 10,000 BC. It has been identified as having "inspired some of the most important developments in human history including the invention of the wheel, the planting of the first cereal crops, and the development of cursive script, mathematics, astronomy, and agriculture."[6]

The "Cradle of Civilisation" is a common term for the area comprising modern Iraq as it was home to the earliest known civilisation, the Sumerian civilisation, which arose in the fertile Tigris-Euphrates river valley of southern Iraq in the Chalcolithic (Ubaid period).[7] It was there, in the late 4th millennium BC, that the world's first known writing system emerged. The Sumerians were also the first known to harness the wheel and create city-states; their writings record the first known evidence of mathematics, astronomy, astrology, written law, medicine, and organised religion.[7] The Sumerian language is a language isolate. The major city-states of the early Sumerian period included Eridu, Bad-tibira, Larsa, Sippar, Shuruppak, Uruk, Kish, Ur, Nippur, Lagash, Girsu, Umma, Hamazi, Adab, Mari, Isin, Kutha, Der, and Akshak.[7] The cities to the north, like Ashur, Arbela (modern Erbil), and Arrapha (modern Kirkuk), were also extant in what was to be called Assyria from the 25th century BC; however, at this stage, they were Sumerian-ruled administrative centers.

Bronze Age

[edit]Sumer emerged as the civilization of Lower Mesopotamia out of the prehistoric Ubaid period (mid-6th millennium BC) in the Early Bronze Age (Uruk period). Classical Sumer ended with the rise of the Akkadian Empire in the 24th century BC. Following the Gutian period, the Ur III kingdom was once again able to unite large parts of southern and central Mesopotamia under a single ruler in the 21st century. It may have eventually disintegrated due to Amorite incursions. The Amorite dynasty of Isin persisted until c. 1600 BC, when southern Mesopotamia was united under Kassite Babylonian rule.

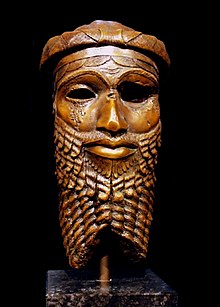

During the Bronze Age, in the 26th century BC, Eannatum of Lagash created a short-lived empire. Later, Lugal-Zage-Si, the priest-king of Umma, overthrew the primacy of the Lagash dynasty in the area, then conquered Uruk, making it his capital, and claimed an empire extending from the Persian Gulf to the Mediterranean.[8] It was during this period that the Epic of Gilgamesh originated, which includes the tale of The Great Flood. The origin and location of Akkad remain unclear. Its people spoke Akkadian, an East Semitic language.[9] Between the 29th and 24th centuries BC, a number of kingdoms and city-states within Iraq began to have Akkadian-speaking dynasties, including Assyria, Ekallatum, Isin, and Larsa. However, the Sumerians remained generally dominant until the rise of the Akkadian Empire (2335–2124 BC), based in the city of Akkad in central Iraq. Sargon of Akkad founded the empire, conquered all the city-states of southern and central Iraq, and subjugated the kings of Assyria, thus uniting the Sumerians and Akkadians in one state. The Akkadian Empire was the first ancient empire of Mesopotamia after the long-lived civilization of Sumer.

He then set about expanding his empire, conquering Gutium, Elam in modern-day Iran, and had victories that did not result in full conquest against the Amorites and Eblaites of the Levant. The empire of Akkad likely fell in the 22nd century BC, within 180 years of its founding, ushering in a "Dark Age" with no prominent imperial authority until the Third Dynasty of Ur. The region's political structure may have reverted to the status quo ante of local governance by city-states.[10]

After the collapse of the Akkadian Empire in the late 22nd century BC, the Gutians occupied the south for a few decades, while Assyria reasserted its independence in the north. Most of southern Mesopotamia was again united under one ruler during the Ur III period, most notably during the rule of the prolific king Shulgi. His accomplishments include the completion of construction of the Great Ziggurat of Ur, begun by his father Ur-Nammu.[11] In 1792 BC, an Amorite ruler named Hammurabi came to power and immediately set about building Babylon into a major city, declaring himself its king. Hammurabi conquered southern and central Iraq, as well as Elam to the east and Mari to the west, then engaged in a protracted war with the Assyrian king Ishme-Dagan for domination of the region, creating the short-lived Babylonian Empire. He eventually prevailed over the successor of Ishme-Dagan and subjected Assyria and its Anatolian colonies. By the middle of the eighteenth century BC, the Sumerians had lost their cultural identity and ceased to exist as a distinct people.[12][13]

It is from the period of Hammurabi that southern Iraq came to be known as Babylonia, while the north had already coalesced into Assyria hundreds of years before. However, his empire was short-lived, and rapidly collapsed after his death, with both Assyria and southern Iraq, in the form of the Sealand Dynasty, falling back into native Akkadian hands. After this, another foreign people, the language-isolate-speaking Kassites, seized control of Babylonia. Iraq was from this point divided into three polities: Assyria in the north, Kassite Babylonia in the south-central region, and the Sealand Dynasty in the far south. The Sealand Dynasty was finally conquered by Kassite Babylonia circa 1380 BC. The origin of the Kassites is uncertain.[14]

The Middle Assyrian Empire (1365–1020 BC) saw Assyria rise to be the most powerful nation in the known world. Beginning with the campaigns of Ashur-uballit I, Assyria destroyed the rival Hurrian-Mitanni Empire, annexed huge swathes of the Hittite Empire for itself, annexed northern Babylonia from the Kassites, forced the Egyptian Empire from the region, and defeated the Elamites, Phrygians, Canaanites, Phoenicians, Cilicians, Gutians, Dilmunites, and Arameans. At its height, the Middle Assyrian Empire stretched from The Caucasus to Dilmun (modern Bahrain), and from the Mediterranean coasts of Phoenicia to the Zagros Mountains of Iran. In 1235 BC, Tukulti-Ninurta I of Assyria took the throne of Babylon.

During the Bronze Age collapse (1200–900 BC), Babylonia was in a state of chaos, dominated for long periods by Assyria and Elam. The Kassites were driven from power by Assyria and Elam, allowing native south Mesopotamian kings to rule Babylonia for the first time, although often subject to Assyrian or Elamite rulers. However, these Akkadian kings were unable to prevent new waves of West Semitic migrants from entering southern Iraq, and during the 11th century BC, Arameans and Suteans entered Babylonia from The Levant, followed in the late 10th to early 9th century BC by the Chaldeans.[15] However, the Chaldeans were absorbed and assimilated into the indigenous population of Babylonia.[16]

Assyria was an Akkadian (East Semitic) kingdom in Upper Mesopotamia, that came to rule regional empires a number of times through history. It was named for its original capital, the ancient city of Assur (Akkadian Aššūrāyu).

Of the early history of the kingdom of Assyria, little is positively known. In the Assyrian King List, the earliest king recorded was Tudiya. He was a contemporary of Ibrium of Ebla, who appears to have lived in the late 25th or early 24th century BC, according to the king list. The foundation of the first true urbanised Assyrian monarchy was traditionally ascribed to Ushpia, a contemporary of Ishbi-Erra of Isin and Naplanum of Larsa.[17] c. 2030 BC.

Assyria had a period of empire from the 19th to 18th centuries BC. From the 14th to 11th centuries BC, Assyria once more became a major power with the rise of the Middle Assyrian Empire.

Iron Age

[edit]

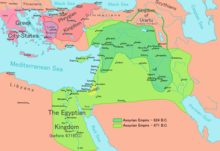

The Neo-Assyrian Empire (911–609 BC) was the dominant political force in the Ancient Near East during the Iron Age, eclipsing Babylonia, Egypt, Urartu, and Elam.[20] Because of its geopolitical dominance and ideology based on world domination, the Neo-Assyrian Empire is regarded by many researchers as the first world empire.[19][21] At its height, the empire ruled over all of Mesopotamia, the Levant, and Egypt, as well as portions of Anatolia, the Arabian Peninsula, and modern-day Iran and Armenia. Under rulers such as Adad-Nirari II, Ashurnasirpal, Shalmaneser III, Semiramis, Tiglath-pileser III, Sargon II, Sennacherib, Esarhaddon, and Ashurbanipal, Iraq became the center of an empire stretching from Persia, Parthia, and Elam in the east to Cyprus and Antioch in the west, and from The Caucasus in the north to Egypt, Nubia, and Arabia in the south.[22]

It was during this period that an Akkadian-influenced form of Eastern Aramaic was adopted by the Assyrians as their lingua franca, and Mesopotamian Aramaic began to supplant Akkadian as the spoken language of the general populace of both Assyria and Babylonia. The descendant dialects of this tongue survive among the Mandaeans of southern Iraq and Assyrians of northern Iraq. The Arabs and the Chaldeans are first mentioned in written history (circa 850 BC) in the annals of Shalmaneser III. The Neo-Assyrian Empire left a legacy of great cultural significance. The political structures established by the Neo-Assyrian Empire became the model for the later empires that succeeded it, and the ideology of universal rule promulgated by the Neo-Assyrian kings inspired similar ideas of rights to world domination in later empires. The Neo-Assyrian Empire became an important part of later folklore and literary traditions in northern Mesopotamia. Judaism, and thus in turn also Christianity and Islam, was profoundly affected by the period of Neo-Assyrian rule; numerous Biblical stories appear to draw on earlier Assyrian mythology and history, and the Assyrian impact on early Jewish theology was immense. Although the Neo-Assyrian Empire is prominently remembered today for the supposed excessive brutality of the Neo-Assyrian army, the Assyrians were not excessively brutal compared to other civilizations.[18][23]

In the late 7th century BC, the Assyrian Empire tore itself apart with a series of brutal civil wars, weakening itself to such a degree that a coalition of its former subjects, including the Babylonians, Chaldeans, Medes, Persians, Parthians, Scythians, and Cimmerians, were able to attack Assyria, finally bringing its empire down by 605 BC.[24]

The short-lived Neo-Babylonian Empire (626–539 BC) succeeded that of Assyria. It failed to attain the size, power, or longevity of its predecessor; however, it came to dominate The Levant, Canaan, Arabia, Israel, and Judah, and even defeated Egypt. Initially, Babylon was ruled by the Chaldeans, who had migrated to the region in the late 10th or early 9th century BC. Its greatest king, Nebuchadnezzar II, rivaled Hammurabi as the greatest king of Babylon. However, by 556 BC, the Chaldeans had been deposed by the Assyrian-born Nabonidus and his son and regent Belshazzar.[citation needed]

The transfer of empire to Babylon marked the first time the city, and southern Mesopotamia in general, had risen to dominate the Ancient Near East since the collapse of Hammurabi's Old Babylonian Empire. The period of Neo-Babylonian rule saw unprecedented economic and population growth and a renaissance of culture and artwork. Nebuchadnezzar II succeeded Nabopolassar in 605 BC. The empire Nebuchadnezzar inherited was among the most powerful in the world. He quickly reinforced his father's alliance with the Medes by marrying Cyaxares's daughter or granddaughter, Amytis. Some sources suggest that the famous Hanging Gardens of Babylon, one of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World, were built by Nebuchadnezzar for his wife (though the existence of these gardens is debated). Nebuchadnezzar's 43-year reign brought a golden age for Babylon, which became the most powerful kingdom in the Middle East.[25]

The Neo-Babylonian period ended with the reign of Nabonidus in 539 BC. To the east, the Persians had been growing in strength, and eventually Cyrus the Great established his dominion over Babylon. The Chaldeans disappeared around this time, though both Assyria and Babylonia endured and thrived under Achaemenid rule (see Achaemenid Assyria). The Persian rulers retained Assyrian Imperial Aramaic as the language of empire, together with the Assyrian imperial infrastructure and an Assyrian style of art and architecture.[citation needed]

Classical Antiquity

[edit]Achaemenid and Seleucid rule

[edit]Mesopotamia was conquered by the Achaemenid Persians under Cyrus the Great in 539 BC, and remained under Persian rule for two centuries.

The Persian Empire fell to Alexander of Macedon in 331 BC and came under Greek rule as part of the Seleucid Empire. Babylon declined after the founding of Seleucia on the Tigris, the new Seleucid Empire capital. The Seleucid Empire at the height of its power stretched from the Aegean in the west to India in the east. It was a major center of Hellenistic culture that maintained the preeminence of Greek customs where a Greek political elite dominated, mostly in the urban areas.[26] The Greek population of the cities who formed the dominant elite were reinforced by immigration from Greece.[26][27] Much of the eastern part of the empire was conquered by the Parthians under Mithridates I of Parthia in the mid-2nd century BC.

Parthian and Roman rule

[edit]

At the beginning of the 2nd century AD, the Romans, led by emperor Trajan, invaded Parthia and conquered Mesopotamia, making it an imperial province. It was returned to the Parthians shortly after by Trajan's successor, Hadrian.

Christianity reached Mesopotamia in the 1st century AD, and Roman Syria in particular became the center of Eastern Rite Christianity and the Syriac literary tradition. Mandeism is also believed to have either originated there around this time or entered as Mandaeans sought refuge from Palestine. Sumerian-Akkadian religious tradition disappeared during this period, as did the last remnants of cuneiform literacy, although temples were still being dedicated to the Assyrian national god Ashur in his home city as late as the 4th century.[28]

Sassanid Empire

[edit]In the 3rd century AD, the Parthians were in turn succeeded by the Sassanid dynasty, which ruled Mesopotamia until the 7th-century Islamic invasion. The Sassanids conquered the independent states of Adiabene, Osroene, Hatra, and finally Assur during the 3rd century. In the mid-6th century, the Persian Empire under the Sassanid dynasty was divided by Khosrow I into four quarters, of which the western one, called Khvārvarān, included most of modern Iraq, and was subdivided into the provinces of Mishān, Asuristān (Assyria), Adiabene, and Lower Media. The term Iraq is widely used in the medieval Arabic sources for the area in the center and south of the modern republic as a geographic rather than a political term, implying no greater precision of boundaries than the term "Mesopotamia" or, indeed, many of the names of modern states before the 20th century.

There was a substantial influx of Arabs in the Sassanid period. Upper Mesopotamia came to be known as Al-Jazirah in Arabic (meaning "The Island" in reference to the "island" between the Tigris and Euphrates rivers), and Lower Mesopotamia came to be known as ʿIrāq-i ʿArab, meaning "the escarpment of the Arabs" (viz. to the south and east of "the island").[29]

Until 602, the desert frontier of the Persian Empire had been guarded by the Arab Lakhmid kings of Al-Hirah. In that year, Shahanshah Khosrow II Aparviz (Persian خسرو پرويز) abolished the Lakhmid kingdom and laid the frontier open to nomad incursions. Farther north, the western quarter was bounded by the Byzantine Empire. The frontier more or less followed the modern Syria-Iraq border and continued northward, passing between Nisibis (modern Nusaybin) as the Sassanian frontier fortress and Dara and Amida (modern Diyarbakır) held by the Byzantines.

Middle Ages

[edit]Islamic conquest

[edit]

The first organized conflict between invading Arab-Muslim forces and occupying Sassanid domains in Mesopotamia seems to have been in 634, when the Arabs were defeated at the Battle of the Bridge. There was a force of some 5,000 Muslims under Abū `Ubayd ath-Thaqafī, which was routed by the Persians. This was followed by Khalid ibn al-Walid's successful campaign, which saw all of Iraq come under Arab rule within a year, with the exception of the Sassanid Empire's capital, Ctesiphon. Around 636, a larger Arab Muslim force under Sa`d ibn Abī Waqqās defeated the main Persian army at the Battle of al-Qādisiyyah and moved on to capture Ctesiphon. By the end of 638, the Muslims had conquered all of the Western Sassanid provinces (including modern Iraq), and the last Sassanid Emperor, Yazdegerd III, had fled to central and then northern Persia, where he was killed in 651.

The Islamic expansions constituted the largest of the Semitic expansions in history. These new arrivals established two new garrison cities, at Kufa, near ancient Babylon, and at Basra in the south and established Islam in these cities, while the north remained largely Assyrian and Christian in character.

Abbasid Caliphate

[edit]

The city of Baghdad, established in the 8th century as the capital of the Abbasid Caliphate, quickly became the leading cultural and intellectual hub of the Muslim world during the Islamic Golden Age. At its peak, Baghdad was the largest and most multicultural city of the Middle Ages, with a population exceeding a million. However, its prominence was dramatically curtailed in the 13th century when the Mongol Empire sacked the city and destroyed its famed library during the Siege of Baghdad (1258).

In the 9th century, the Abbasid Caliphate entered a period of decline. During the late 9th to early 11th centuries, a period known as the "Iranian Intermezzo", parts of (the modern territory of) Iraq were governed by a number of minor Iranian emirates, including the Tahirids, Saffarids, Samanids, Buyids and Sallarids. Tughril, the founder of the Seljuk Empire, captured Baghdad in 1055. In spite of having lost all governance, the Abbasid caliphs nevertheless maintained a highly ritualized court in Baghdad and remained influential in religious matters, maintaining the orthodoxy of their Sunni sect in opposition to the Ismaili and Shia sects of Islam.

Mongol invasion

[edit]

In the later 11th century, Iraq fell under the rule of the Khwarazmian dynasty. Both Turkic secular rule and Abbasid caliphate came to an end with the Mongol invasions of the 13th century.[30] The Mongols under Genghis Khan had conquered Khwarezmia by 1221, but Iraq proper gained a respite due to the death of Genghis Khan in 1227 and the subsequent power struggles. Möngke Khan from 1251 began a renewed expansion of the Mongol Empire, and when caliph al-Mustasim refused to submit to the Mongols, Baghdad was besieged and captured by Hulagu Khan in 1258. With the destruction of the Abbasid Caliphate, Hulagu had an open route to Syria and moved against the other Muslim powers in the region.[31]

Turco-Mongol rule

[edit]Iraq now became a province on the southwestern fringes of the Ilkhanate and Baghdad would never regain its former importance.

The Jalayirids were a Mongol Jalayir dynasty[32] which ruled over Iraq and western Persia[33] after the breakup of the Ilkhanate in the 1330s. The Jalayirid sultanate lasted about fifty years, until disrupted by Tamerlane's conquests and the revolts of the "Black Sheep Turks" or Qara Qoyunlu Turkmen. After Tamerlane's death in 1405, there was a brief attempt to re-establish the sultanate in southern Iraq and Khuzistan. The Jalayirids were finally eliminated by Kara Koyunlu in 1432.

Ottoman and Mamluk rule

[edit]During the late 14th and early 15th centuries, the Qara Qoyunlu, or Black Sheep Turkmens, ruled the area now known as Iraq. In 1466, the Aq Qoyunlu, or White Sheep, defeated the Qara Qoyunlu and took control. From 1508, as with all territories of the former White Sheep Turkmen, Iraq fell into the hands of the Iranian Safavids. With the Treaty of Zuhab in 1639, most of the territory of present-day Iraq came under the control of the Ottoman Empire as the eyalet of Baghdad as a result of wars with the neighboring rival, Safavid Iran. Throughout most of the period of Ottoman rule (1533–1918), the territory of present-day Iraq was a battle zone between rival regional empires and tribal alliances. Iraq was divided into three vilayets:

In the 16th century, the Portuguese commanded by António Tenreiro crossed from Aleppo to Basra in 1523, attempting to make alliances with local lords in the name of the Portuguese king. In 1550, the local kingdom of Basra and tribal rulers relied on the Portuguese against the Ottomans, leading to threats of invasion and conquest by the Portuguese. From 1595, the Portuguese acted as military protectors of Basra, and in 1624, they helped the Ottoman pasha of Basra repel a Persian invasion. The Portuguese were granted a share of customs revenue and exemption from tolls. From approximately 1625 to 1668, Basra and the Delta marshes were in the hands of local chiefs independent of the Ottoman administration in Baghdad. In the 17th century, frequent conflicts with the Safavids sapped the strength of the Ottoman Empire and weakened its control over its provinces. The nomadic population swelled with the influx of bedouins from Najd, leading to raids on settled areas that became difficult to curb.

During the years 1747–1831, Iraq was ruled by a Mamluk dynasty of Georgian origin, who succeeded in obtaining autonomy from the Ottoman Empire. They suppressed tribal revolts, curbed the power of the Janissaries, restored order, and introduced a program of modernization in the economy and military. In 1802, Wahhabis from Najd attacked Karbala in Iraq, killing up to 5,000 people and plundering the Imam Husayn Shrine. In 1831, the Ottomans managed to overthrow the Mamluk regime and reimposed their direct control over Iraq. The population of Iraq, estimated at 30 million in 800 AD, had dwindled to only 5 million by the start of the 20th century.

20th century

[edit]British mandate of Mesopotamia

[edit]

Ottoman rule over Iraq lasted until World War I, when the Ottomans sided with Germany and the Central Powers. In the Mesopotamian campaign against the Central Powers, British forces invaded the country and suffered a defeat at the hands of the Turkish army during the Siege of Kut (1915–16). However, the British ultimately won the Mesopotamian Campaign with the capture of Baghdad in March 1917. During the war, the British employed the help of several Assyrian, Armenian, and Arab tribes against the Ottomans, who in turn employed the Kurds as allies. Following the defeat of the Ottoman Empire and its subsequent division, the British Mandate of Mesopotamia was established by the League of Nations mandate.

In line with their "Sharifian Solution" policy, the British established a monarchy on 23 August 1921, with Faisal I of Iraq as king, who was previously King of Syria but was forced out by the French. The official English name of the country simultaneously changed from Mesopotamia to the endonymic Iraq.[34] Likewise, British authorities selected Sunni Arab elites from the region for appointments to government and ministry offices.[specify][35][page needed][36] The royal family were Hashemites, who were also rulers of the neighboring Emirate of Transjordan, which later became the Kingdom of Jordan.[35]

During the rise of the Zionist movement and Arab nationalism, Faisal envisioned a federation consisting of the modern states of Iraq, Lebanon, Syria, and Palestine, including both modern Palestine and Israel.[37] He also signed the Faisal–Weizmann agreement.

Faced with spiraling costs and influenced by the public protestations of the war hero T. E. Lawrence,[38] Britain replaced Arnold Wilson in October 1920 with a new Civil Commissioner, Sir Percy Cox.[39] Cox managed to quell a rebellion and was also responsible for implementing the policy of close cooperation with Iraq's Sunni minority.[40] Slavery was abolished in Iraq in the 1920s.[41] Britain granted independence to the Kingdom of Iraq in 1932,[42] on the urging of King Faisal, though the British retained military bases and local militia in the form of Assyrian Levies. King Ghazi ruled as a figurehead after King Faisal's death in 1933. His rule, which lasted until his death in 1939, was undermined by numerous attempted military coups until his death in 1939. His underage son, Faisal II succeeded him, with 'Abd al-Ilah as Regent.[citation needed]

Independent Kingdom of Iraq

[edit]

Establishment of Arab Sunni domination in Iraq was followed by Assyrian, Yazidi and Shi'a unrests, which were all brutally suppressed. In 1936, the first military coup took place in the Kingdom of Iraq, as Bakr Sidqi succeeded in replacing the acting Prime Minister with his associate. Multiple coups followed in a period of political instability, peaking in 1941.

During World War II, Iraqi regime of Regent 'Abd al-Ilah was overthrown in 1941 by the Golden Square officers, headed by Rashid Ali. The short lived pro-Nazi government of Iraq was defeated in May 1941 by the allied forces (with local Assyrian and Kurdish help) in the Anglo-Iraqi War. Iraq was later used as a base for allied attacks on Vichy-French held Mandate of Syria and support for the Anglo-Soviet invasion of Iran.[43]

In 1945, Iraq joined the United Nations and became a founding member of the Arab League. At the same time, the Kurdish leader Mustafa Barzani led a rebellion against the central government in Baghdad. After the failure of the uprising, Barzani and his followers fled to the Soviet Union.

In 1948, massive violent protests known as the Al-Wathbah uprising broke out across Baghdad with partial communist support, having demands against the government's treaty with Britain. Protests continued into spring and were interrupted in May when martial law was enforced as Iraq entered the failed 1948 Arab–Israeli War along with other Arab League members.

In February 1958, King Hussein of Jordan and `Abd al-Ilāh proposed a union of Hāshimite monarchies to counter the recently formed Egyptian-Syrian union. The prime minister Nuri as-Said wanted Kuwait to be part of the proposed Arab-Hāshimite Union. Shaykh `Abd-Allāh as-Salīm, the ruler of Kuwait, was invited to Baghdad to discuss Kuwait's future. This policy brought the government of Iraq into direct conflict with Britain, which did not want to grant independence to Kuwait. At that point, the monarchy found itself completely isolated. Nuri as-Said was able to contain the rising discontent only by resorting to even greater political oppression.

Republic of Iraq

[edit]

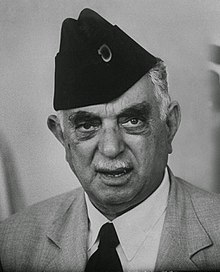

In 1958, inspired by Gamal Abdel Nasser of Egypt, officers from the Nineteenth Brigade, 3rd Division, known as "The Four Colonels," under the leadership of Brigadier Abd al-Karīm Qāsim (known as "az-Za`īm", 'the leader') and Colonel Abdul Salam Arif overthrew the Hashemite monarchy on July 14, 1958. The new government proclaimed Iraq to be a republic and rejected the idea of a union with Jordan. Iraq's activity in the Baghdad Pact ceased.

This revolution was strongly anti-imperial and anti-monarchical in nature and had strong socialist elements.[44][45] Numerous people were killed in the coup, including King Faisal II, Prince Abd al-Ilah, and Nuri al-Sa'id, as well as members of the royal family, which came to be known as the "Royal family massacre".[45] After burial, their bodies were dragged through the streets of Baghdad by their opponents and mutilated.[46][45] The short-lived federation between Jordan and Iraq was abolished by King Hussein following the coup in 1958.[45]

Abd al-Karim Qasim promoted a civic nationalism in Iraq, which asserted the belief that Iraqis are a nation and emphasized the cultural unity of Iraqis of different ethnoreligious groups such as Mesopotamian Arabs, Kurds, Turkmens, Assyrians, Yazidis, Mandeans, Yarsans, and others. His vision of nationalism involved the recognition of an Iraqi identity stemming from ancient Mesopotamia, including its civilizations of Sumer, Akkad, Babylonia, and Assyria.[47]

Qasim controlled Iraq through military rule and began forcibly redistributing surplus land owned by some citizens in 1958.[48][49] The Iraqi state emblem under Qasim was largely based on the Mesopotamian symbol of Shamash, avoiding pan-Arab symbolism by incorporating elements of Socialist heraldry.[50] Under Qasim, freedom of religion was granted to religious minorities, and early restrictions on Jews were removed, leading to their reintegration into society.[51][52]

Qasim's political ideologies were based on Iraqi nationalism instead of Arab nationalism, and he refused to join Gamal Abdel Nasser's political union between Egypt and Syria, known as the United Arab Republic. In 1959, Colonel Abd al-Wahab al-Shawaf led an uprising in Mosul against Qasim with the aim of joining the United Arab Republic, but was defeated by the government.[50]

Iraq withdrew from the Baghdad Pact in 1959, leading to strained relations with the West and developing a close alliance with the Soviet Union.[50][53] Qasim began claiming Kuwait as part of Iraq when it was officially declared an independent country in 1961.[53] During Ottoman rule, Kuwait was part of Basra Province and was separated by the British to establish the Kuwait protectorate.[53] In response, the United Kingdom sent its armed forces to the Iraq–Kuwait border, and Qasim was forced to back down.[53]

In 1961, Kurdish nationalist movements, led by Mustafa Barzani's Kurdistan Democratic Party, launched an armed rebellion against the Iraqi government, seeking Kurdish autonomy.[50] The government faced challenges in quelling the Kurdish uprising, leading to intermittent conflict between Kurdish forces and the Iraqi military.[50] The armed rebellion escalated into war, which officially lasted for nine years until 1970, during which numerous coups occurred.[50]

Ba'athist Iraq

[edit]

Qāsim was assassinated in February 1963 when the Ba'ath Party took power under the leadership of General Ahmed Hassan al-Bakr (prime minister) and Colonel Abdul Salam Arif (president). In June 1963, Syria, which by then had also fallen under Ba'athist rule, took part in the Iraqi military campaign against the Kurds by providing aircraft, armoured vehicles, and a force of 6,000 soldiers. Several months later, Abd as-Salam Muhammad Arif led a successful coup against the Ba'ath government. Arif declared a ceasefire in February 1964, which provoked a split among Kurdish urban radicals on one hand and Peshmerga (Freedom fighters) forces led by Barzani on the other.

On April 13, 1966, President Abdul Salam Arif died in a helicopter crash and was succeeded by his brother, General Abdul Rahman Arif. Following this unexpected death, the Iraqi government launched a last-ditch effort to defeat the Kurds. This campaign failed in May 1966, when Barzani forces thoroughly defeated the Iraqi Army at the Battle of Mount Handrin, near Rawanduz. Following the Six-Day War of 1967, the Ba'ath Party felt strong enough to retake power in 1968. Ahmed Hassan al-Bakr became president and chairman of the Revolutionary Command Council (RCC). The Ba'ath government started a campaign to end the Kurdish insurrection, which stalled in 1969 due to internal power struggles and tensions with Iran. The war ended with more than 100,000 casualties and little achievement for both sides.

In March 1970, a peace plan was announced that provided for broader Kurdish autonomy and gave Kurds representation in government bodies, to be implemented in four years.[54] Despite this, the Iraqi government embarked on an Arabization program in the oil-rich regions of Kirkuk and Khanaqin. By 1974, tensions escalated again, leading to the Second Kurdish Iraqi War, which lasted until 1975. The 1975 peace treaty between Iraq and Iran resolved the Shatt al-Arab dispute, leading to Iran withdrawing support for the Kurdish rebels and their subsequent defeat by the Iraqi government.[55][56]

Under Saddam Hussein

[edit]

In July 1979, President Ahmed Hassan al-Bakr was forced to resign by Saddam Hussein, who assumed the offices of both President and Chairman of the Revolutionary Command Council. Saddam then purged his opponents including those from within the Baath party.

- Iraq's Territorial Claims to Neighboring Countries

Iraq's territorial claims to neighboring countries were largely due to the plans and promises of the Entente countries in 1919–1920, when the Ottoman Empire was divided, to create a more extensive Arab state in Iraq and Jazeera, which would also include significant territories of eastern Syria, southeastern Turkey, all of Kuwait and Iran’s border areas, which are shown on this English map of 1920.

Territorial disputes with Iran led to an inconclusive and costly eight-year war, the Iran–Iraq War (1980–1988, termed Qādisiyyat-Saddām – 'Saddam's Qādisiyyah'), which devastated the economy. Iraq falsely declared victory in 1988 but actually only achieved a weary return to the status quo ante bellum, meaning both sides retained their original borders.

The war began when Iraq invaded Iran, launching a simultaneous invasion by air and land into Iranian territory on 22 September 1980, following a long history of border disputes, and fears of Shia insurgency among Iraq's long-suppressed Shia majority influenced by the Iranian Revolution. Iraq was also aiming to replace Iran as the dominant Persian Gulf state. The United States supported Saddam Hussein in the war against Iran.[57] Although Iraq hoped to take advantage of the revolutionary chaos in Iran and attacked without formal warning, they made only limited progress into Iran and within several months were repelled by the Iranians who regained virtually all lost territory by June 1982. For the next six years, Iran was on the offensive.[58] Despite calls for a ceasefire by the United Nations Security Council, hostilities continued until 20 August 1988. The war finally ended with a United Nations-brokered ceasefire in the form of United Nations Security Council Resolution 598, which was accepted by both sides. It took several weeks for the Iranian armed forces to evacuate Iraqi territory to honor pre-war international borders between the two nations (see 1975 Algiers Agreement). The last prisoners of war were exchanged in 2003.[58][59]

The war came at a great cost in lives and economic damage—half a million Iraqi and Iranian soldiers, as well as civilians, are believed to have died in the war with many more injured—but it brought neither reparations nor change in borders. The conflict is often compared to World War I,[60] in that the tactics used closely mirrored those of that conflict, including large scale trench warfare, manned machine-gun posts, bayonet charges, use of barbed wire across trenches, human wave attacks across no-man's land, and extensive use of chemical weapons such as mustard gas by the Iraqi government against Iranian troops and civilians as well as Iraqi Kurds. At the time, the UN Security Council issued statements that "chemical weapons had been used in the war." However, in these UN statements, it was never made clear that it was only Iraq that was using chemical weapons, so it has been said that "the international community remained silent as Iraq used weapons of mass destruction against Iranian as well as Iraqi Kurds" and it is believed.

A long-standing territorial dispute was the ostensible reason for Iraq's invasion of Kuwait in 1990. In November 1990, the UN Security Council adopted Resolution 678, permitting member states to use all necessary means, authorizing military action against the Iraqi forces occupying Kuwait and demanded a complete withdrawal by January 15, 1991. When Saddam Hussein failed to comply with this demand, the Gulf War (Operation "Desert Storm") ensued on January 17, 1991. Estimates range from 1,500 to as many as 30,000 Iraqi soldiers killed, as well as less than a thousand civilians.[61][62]

In March 1991 revolts in the Shia-dominated southern Iraq started involving demoralized Iraqi Army troops and the anti-government Shia parties. Another wave of insurgency broke out shortly afterwards in the Kurdish populated northern Iraq (see 1991 Iraqi uprisings). Although they presented a serious threat to the Iraqi Ba'ath Party regime, Saddam Hussein managed to suppress the rebellions with massive and indiscriminate force and maintained power. They were ruthlessly crushed by the loyalist forces spearheaded by the Iraqi Republican Guard and the population was successfully terrorized. During the few weeks of unrest tens of thousands of people were killed. Many more died during the following months, while nearly two million Iraqis fled for their lives. In the aftermath, the government intensified the forced relocating of Marsh Arabs and the draining of the Iraqi marshlands, while the Coalition established the Iraqi no-fly zones.

On 6 August 1990, after the Iraqi invasion of Kuwait, the U.N. Security Council adopted Resolution 661 which imposed economic sanctions on Iraq, providing for a full trade embargo, excluding medical supplies, food and other items of humanitarian necessity, these to be determined by the Security Council sanctions committee. After the end of the Gulf War and after the Iraqi withdrawal from Kuwait, the sanctions were linked to removal of weapons of mass destruction by Resolution 687.[63] To varying degrees, the effects of government policy, the aftermath of Gulf War and the sanctions regime have been blamed for these conditions.

The effects of the sanctions on the civilian population of Iraq have been disputed.[64][65] Whereas it was widely believed that the sanctions caused a major rise in child mortality, recent research has shown that commonly cited data were fabricated by the Iraqi government and that "there was no major rise in child mortality in Iraq after 1990 and during the period of the sanctions."[66][67][68] An oil for food program was established in 1996 to ease the effects of sanctions.

Iraqi cooperation with UN weapons inspection teams was questioned on several occasions during the 1990s. UNSCOM chief weapons inspector Richard Butler withdrew his team from Iraq in November 1998 because of Iraq's lack of cooperation. The team returned in December.[69] Butler prepared a report for the UN Security Council afterwards in which he expressed dissatisfaction with the level of compliance [2]. The same month, US President Bill Clinton authorized air strikes on government targets and military facilities. Air strikes against military facilities and alleged WMD sites continued into 2002.

U.S. invasion and the aftermath (2003–present)

[edit]2003 U.S. invasion

[edit]After the terrorist attacks on New York and Washington in the United States in 2001 were linked to the group formed by the multi-millionaire Saudi Osama bin Laden, American foreign policy began to call for the removal of the Ba'ath government in Iraq. Neoconservative think-tanks in Washington had for years been urging regime change in Baghdad. On August 14, 1998, President Clinton signed Public Law 105–235, which declared that ‘‘the Government of Iraq is in material and unacceptable breach of its international obligations.’’ It urged the President ‘‘to take appropriate action, in accordance with the Constitution and relevant laws of the United States, to bring Iraq into compliance with its international obligations.’’ Several months later, Congress enacted the Iraq Liberation Act of 1998 on October 31, 1998. This law stated that it "should be the policy of the United States to support efforts to remove the regime headed by Saddam Hussein from power in Iraq and to promote the emergence of a democratic government to replace that regime." It was passed 360 - 38 by the United States House of Representatives and 99–0 by the United States Senate in 1998.

The US urged the United Nations to take military action against Iraq. American president George W. Bush stated that Saddām had repeatedly violated 16 UN Security Council resolutions. The Iraqi government rejected Bush's assertions. A team of U.N. inspectors, led by Swedish diplomat Hans Blix was admitted, into the country; their final report stated that Iraqis capability in producing "weapons of mass destruction" was not significantly different from 1992 when the country dismantled the bulk of their remaining arsenals under terms of the ceasefire agreement with U.N. forces, but did not completely rule out the possibility that Saddam still had weapons of mass destruction. The United States and the United Kingdom charged that Iraq was hiding WMD and opposed the team's requests for more time to further investigate the matter. Resolution 1441 was passed unanimously by the UN Security Council on November 8, 2002, offering Iraq "a final opportunity to comply with its disarmament obligations" that had been set out in several previous UN resolutions, threatening "serious consequences" if the obligations were not fulfilled. The UN Security Council did not issue a resolution authorizing the use of force against Iraq.

In March 2003, the United States and the United Kingdom, with military aid from other nations, invaded Iraq.

Over the following years in the U.S. occupation of Iraq, Iraq disintegrated into a civil war from 2006 to 2008, and the situation deteriorated in 2011 which later escalated into a renewed war following ISIL gains in the country in 2014. By 2015, Iraq was effectively divided, the central and southern part being controlled by the government, the northwest by the Kurdistan Regional Government and the western part by the Islamic State. IS was expelled from Iraq in 2017, but a low-intensity ISIL insurgency continues mostly in the rural parts of northern western parts of the country, due to Iraq's long border with Syria.[70]

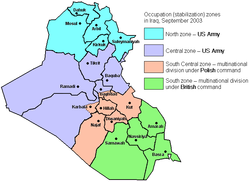

Occupation (2003–11)

[edit]

In 2003, after the American and British invasion, Iraq was occupied by U.S.-led Coalition forces. On May 23, 2003, the UN Security Council unanimously approved a resolution lifting all economic sanctions against Iraq. As the country struggled to rebuild after three wars and a decade of sanctions, it was plagued by violence between a growing Iraqi insurgency and occupation forces. Saddam Hussein, who vanished in April, was captured on December 13, 2003 in ad-Dawr, Saladin Governorate.

Jay Garner was appointed Interim Civil Administrator with three deputies, including Tim Cross. Garner was replaced in May 2003 by Paul Bremer, who was himself replaced by John Negroponte on April 19, 2004. Negroponte was the last US interim administrator and left Iraq in 2005. A parliamentary election was held in January 2005, followed by the drafting and ratification of a constitution and a further parliamentary election in December 2005.

Terrorism emerged as a threat to Iraq's people not long after the invasion of 2003. Al Qaeda now had a presence in the country, in the form of several terrorist groups formerly led by Abu Musab Al Zarqawi. Al Zarqawi was a Jordanian militant Islamist who ran a militant training camp in Afghanistan. He became known after going to Iraq and being responsible for a series of bombings, beheadings and attacks during the Iraq war. Al Zarqawi was killed on June 7, 2006. Many foreign fighters and former Ba'ath Party officials also joined the insurgency, which was mainly aimed at attacking American forces and Iraqis who worked with them. The most dangerous insurgent area was the Sunni Triangle, a mostly Sunni-Muslim area just north of Baghdad.

Reported acts of violence conducted by an uneasy tapestry of insurgents steadily increased by the end of 2006.[71] Sunni jihadist forces including Al Qaeda in Iraq continued to target Shia civilians, notably in the 23 February 2006 attack on the Al Askari Mosque in Samarra, one of Shi'ite Islam's holiest sites leading to a civil war between Sunni and Shia militants in Iraq. Analysis of the attack suggested that the Mujahideen Shura Council and Al-Qaeda in Iraq were responsible, and that the motivation was to provoke further violence by outraging the Shia population.[72] In mid-October 2006, a statement was released stating that the Mujahideen Shura Council had been disbanded and was replaced by the "Islamic State of Iraq". It was formed to resist efforts by the U.S. and Iraqi authorities to win over Sunni supporters of the insurgency. Shia militias, some of whom were associated with elements in the Iraq government, reacted with reprisal acts against the Sunni minority. A cycle of violence thus ensued whereby Sunni insurgent attacks were followed reprisals by Shiite militias, often in the form of Shi'ite death squads that sought out and killed Sunnis. Following a surge in U.S. troops in 2007 and 2008, violence in Iraq began to decrease. The U.S. ended their main military presence in 2011, however, resulting in renewed escalation into war.[73]

Insurgency and war (2011–2017)

[edit]The departure of US troops from Iraq in 2011 triggered a renewed insurgency and by a spillover of the Syrian civil war into Iraq. By 2013, the insurgency escalated into a state renewed war, the central government of Iraq being opposed by various factions, primarily radical Sunni forces.

The Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant invaded Iraq in 2013–14 and seized the majority of Al Anbar Governorate,[74] including the cities of Fallujah,[75] Al Qaim,[76] Abu Ghraib and (in May 2015) Ramadi,[77] leaving them in control of 90% of Anbar.[78][79] Tikrit, Mosul and most of the Nineveh province, along with parts of Salahuddin, Kirkuk and Diyala provinces, were seized by insurgent forces in the June 2014 offensive.[80] ISIL also captured Sinjar and a number of other towns in the August 2014 offensive, but were halted by the Sinjar offensive launched in December 2014 by Kurdish Peshmerga and YPG forces. The war ended with a government victory in December 2017.[81]

On 30 April 2016, thousands of protesters entered the Green Zone in Baghdad and occupied the Iraqi parliament building. This happened after the Iraqi parliament did not approve new government ministers. The protesters included supporters of Shia cleric Muqtada Al Sadr. Although Iraqi security forces were present, they did not attempt to stop the protesters from entering the parliament building.[82]

Continued ISIL insurgency and protests (2017–present)

[edit]Tensions between the federal Iraqi government and Kurdistan Region arising from the Kurdistan Region independence referendum of 25 September 2017 escalated into armed conflict in October 2017. As a result of the conflict, Kurdistan Region lost a fifth of the land mass it had administered prior to the conflict and was forced to cancel the results of the referendum.

By 2018, violence in Iraq was at its lowest level in ten years.[83]

Protests over deteriorating economic conditions and state corruption started in July 2018 in Baghdad and other major Iraqi cities, mainly in the central and southern provinces. The latest nationwide protests, erupting in October 2019, had a death toll of at least 93 people, including police.[84]

In November 2021, Iraqi Prime Minister Mustafa al-Kadhimi survived a failed assassination attempt.[85]

Cleric Muqtada al-Sadr's Sadrist Movement was the biggest winner in the 2021 parliamentary elections.[86] Governmental stalemate lead to the 2022 Iraqi political crisis.[87]

In October 2022, Abdul Latif Rashid was elected as the new President of Iraq after winning the parliamentary election against incumbent Barham Salih, who was running for a second term. The presidency is largely ceremonial and is traditionally held by a Kurd.[88] On 27 October 2022, Mohammed Shia al-Sudani, close ally of former Prime Minister Nouri al-Maliki, took the office to succeed Mustafa al-Kadhimi as new Prime Minister of Iraq.[89]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Murray, Tim (2007). Milestones in Archaeology: A Chronological Encyclopedia. Bloomsbury Academic. p. 454. ISBN 978-1576071861.

- ^ Edwards, Owen (2010). "The Skeletons of Shanidar Cave". Smithsonian.

- ^ Edwards, Owen (March 2010). "The Skeletons of Shanidar Cave". Smithsonian. Retrieved 17 October 2014.

- ^ a b Ralph S. Solecki, Rose L. Solecki, and Anagnostis P. Agelarakis (2004). The Proto-Neolithic Cemetery in Shanidar Cave. Texas A&M University Press. pp. 3–5. ISBN 9781585442720.

- ^ Carter, Robert A. and Philip, Graham Beyond the Ubaid: Transformation and Integration in the Late Prehistoric Societies of the Middle East (Studies in Ancient Oriental Civilization, Number 63) The Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago (2010) ISBN 978-1-885923-66-0 p.2, at http://oi.uchicago.edu/research/pubs/catalog/saoc/saoc63.html Archived 15 November 2013 at the Wayback Machine; "Radiometric data suggest that the whole Southern Mesopotamian Ubaid period, including Ubaid 0 and 5, is of immense duration, spanning nearly three millennia from about 6500 to 3800 B.C".

- ^ Milton-Edwards, Beverley (May 2003). "Iraq, past, present and future: a thoroughly-modern mandate?". History & Policy. United Kingdom. Archived from the original on 8 December 2010. Retrieved 9 December 2010.

- ^ a b c Charles Keith Maisels (24 October 2005). The Near East: Archaeology in the 'Cradle of Civilization'. Routledge. pp. 6–109. ISBN 978-1-134-66469-6.

- ^ Roux, Georges (1993), Ancient Iraq (Penguin)

- ^ "Akkad". World History Encyclopedia. Retrieved 18 August 2017.

- ^ Zettler (2003), pp. 24–25. "Moreover, the Dynasty of Akkade's fall did not lead to social collapse, but the re-emergence of the normative political organization. The southern cities reasserted their independence, and if we know little about the period between the death of Sharkalisharri and the accession of Urnamma, it may be due more to accidents of discovery than because of widespread 'collapse.' The extensive French excavations at Tello produced relevant remains dating right through the period."

- ^ "The Ziggurat of Ur". British Museum. Retrieved 24 November 2017.

- ^ Wolkstein, Diane; Kramer, Samuel Noah (1983). Inanna: Queen of Heaven and Earth: Her Stories and Hymns from Sumer. New York City, New York: Harper&Row Publishers. pp. 118–119. ISBN 978-0-06-090854-6.

- ^ Kramer, Samuel Noah (1963). The Sumerians: Their History, Culture, and Character. Chicago, Illinois: University of Chicago Press. pp. 71–72. ISBN 978-0-226-45238-8.

- ^ J. A. Brinkman, "Kassiten (Kassû)," RLA, vol. 5 (1976–80

- ^ A. Leo Oppenheim – Ancient Mesopotamia

- ^ George Roux – Ancient Iraq – p 281

- ^ According to the Assyrian King List and Georges Roux, Ancient Iraq, p. 187.

- ^ a b Aberbach 2003, p. 4.

- ^ a b Düring 2020, p. 133.

- ^ "Black Obelisk, K. C. Hanson's Collection of Mesopotamian Documents". K.C. Hansen. Archived from the original on 9 July 2017. Retrieved 23 November 2014.

- ^ Liverani, Mario (2017). "Thoughts on the Assyrian Empire and Assyrian Kingship". Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons. p. 536. ISBN 978-1-118-32524-7.

- ^ "Neo-Assyrian Empire". World History Encyclopedia. Retrieved 7 February 2022.

- ^ Frahm, Eckart (2017). A Companion to Assyria. Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons Hoboken. p. 196. ISBN 978-1-118-32524-7.

- ^ Georges Roux – Ancient Iraq

- ^ Joshua J, Mark (2018). "Nebuchadnezzar II". World History Encyclopedia.

- ^ a b Steven C. Hause, William S. Maltby (2004). Western civilization: a history of European society. Thomson Wadsworth. p. 76. ISBN 978-0-534-62164-3.

The Greco-Macedonian Elite. The Seleucids respected the cultural and religious sensibilities of their subjects but preferred to rely on Greek or Macedonian soldiers and administrators for the day-to-day business of governing. The Greek population of the cities, reinforced until the second century BCE by immigration from Greece, formed a dominant, although not especially cohesive, elite.

- ^ Glubb, Sir John Bagot (1967). Syria, Lebanon, Jordan. Thames & Hudson. p. 34. OCLC 585939.

In addition to the court and the army, Syrian cities were full of Greek businessmen, many of them pure Greeks from Greece. The senior posts in the civil service were also held by Greeks. Although the Ptolemies and the Seleucids were perpetual rivals, both dynasties were Greek and ruled by means of Greek officials and Greek soldiers. Both governments made great efforts to attract immigrants from Greece, thereby adding yet another racial element to the population.

- ^ George Roux – Ancient Iraq

- ^ possibly an Arabic folk etymology of an older toponym deriving from the name of Uruk, see name of Iraq.

- ^ Thomas T. Allsen Culture and Conquest in Mongol Eurasia, p.84

- ^ Morgan. The Mongols. pp. 132–135.

- ^ Bayne Fisher, William "The Cambridge History of Iran", p.3: "(From then until the Timur's invasion of the country, Iran was under the rule of various rival petty princes of whom henceforth only the Jalayirids could claim Mongol)

- ^ The History Files Rulers of Persia Archived 2021-05-12 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "How Mesopotamia Became Iraq (and Why It Matters)". Los Angeles Times. 2 September 1990. Retrieved 2 August 2022.

- ^ a b Tripp, Charles (2002). A History of Iraq. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-52900-6. Retrieved 17 August 2016.

- ^ Luedke, Tilman (2008). "Iraq". Oxford Encyclopedia of the Modern World. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/acref/9780195176322.001.0001. ISBN 978-0-19-517632-2. Retrieved 13 June 2018.

- ^ Masalha 1991, p. 684.

- ^ Wilson, Jeremy (1998). Lawrence of Arabia: The Authorised Biography of T. E. Lawrence. Stroud: Sutton. ISBN 978-0-7509-1877-0.

The exploits of T.E. Lawrence as British liaison officer in the Arab Revolt, recounted in his work Seven Pillars of Wisdom, made him one of the most famous Englishmen of his generation. This biography explores his life and career including his correspondence with writers, artists, and politicians.

- ^ "Cox, Sir Percy Zachariah (1864–1937), diplomatist and colonial administrator". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. 2004. doi:10.1093/ref/32604. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- ^ Liam Anderson; Gareth Stansfield (2005). The Future of Iraq: Dictatorship, Democracy, Or Division?. Palgrave Macmillan. p. 6. ISBN 978-1-4039-7144-9. Archived from the original on 25 January 2021. Retrieved 30 November 2018.

Sunni control over the levels of power and the distribution of the spoils of office has had predictable consequences - a simmering resentment on the part of the Shi'a...

- ^ Williams, Timothy (2 December 2009). "In Iraq's African Enclave, Color Is Plainly Seen". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 3 December 2009.

- ^ Ongsotto et al. Asian History Module-based Learning Ii' 2003 Ed. p69. [1]

- ^ Robert Lyman (2006). Iraq 1941: The Battles For Basra, Habbaniya, Fallujah and Baghdad. Osprey Publishing. pp. 12–17. ISBN 9781841769912.

- ^ "60 years on, Iraqis reflect on the coup that killed King Faisal II". Arab News. 2018-07-15. Retrieved 2024-04-30.

- ^ a b c d Cleveland, William (2016). A History of the Modern Middle East. Boulder, CO: Westview Press.

- ^ "Faisal II | King, Iraq, & Death | Britannica". www.britannica.com. 2024-04-26. Retrieved 2024-04-30.

- ^ Reich, Bernard. Political leaders of the contemporary Middle East and North Africa: A Bibliographical Dictionary. Westport, Connecticut, USA: Greenwood Press, Ltd, 1990. Pp. 245.

- ^ "ʿAbd al-Karīm Qāsim | Iraqi Prime Minister, Revolutionary Leader | Britannica". www.britannica.com. 2024-04-03. Retrieved 2024-04-30.

- ^ Taylor, Katharine (May 2018). "Revolutionary Fervor: The History and Legacy of Communism in Abd al-Karim Qasim's Iraq 1958-1963". hdl:2152/65296.

- ^ a b c d e f "Abdul Karim Qasim – A–Z Index – The Kurdistan Memory Programme". kurdistanmemoryprogramme.com. Retrieved 2024-04-30.

- ^ katzcenterupenn. "What Do You Know? Iraq's Jewish History". Herbert D. Katz Center for Advanced Judaic Studies. Retrieved 2024-07-28.

- ^ Haifa, Prof Yehudit Henshke, University of (2021-12-26). "Abd al-Karim Qasim and treatment to Jews, The Preservation of Jewish Languages and Cultures in memory of Hayyim (Marani) Trabelsy". Mother Tongue. Retrieved 2024-07-28.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c d Tripp, Charles. A History of Iraq, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 2002, p.165

- ^ G.S. Harris, Ethnic Conflict and the Kurds, Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, pp.118–120, 1977

- ^ Şahin, Tuncay. "What's the Algiers Agreement between Iran and Iraq about?". What's the Algiers Agreement between Iran and Iraq about?. Retrieved 2024-07-28.

- ^ Anderson, Giulia Valeria (2019-10-21). "US-Kurdish Relations: The 2nd Iraqi-Kurdish War and the Al-Anfal Campaigns".

- ^ Tyler, Patrick E. "Officers Say U.S. Aided Iraq in War Despite Use of Gas" Archived 2017-06-30 at the Wayback Machine New York Times August 18, 2002.

- ^ a b Molavi, Afshin (2005). The Soul of Iran. Norton. p. 152.

- ^ Fathi, Nazila (14 March 2003). "Threats And Responses: Briefly Noted; Iran-Iraq Prisoner Deal". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 17 December 2008. Retrieved 16 February 2017.

- ^ Abrahamian, Ervand, A History of Modern Iran, Cambridge, 2008, p.171

- ^ Findlay, Justin (6 October 2017). "What Was Operation Desert Storm?". WorldAtlas. Archived from the original on 5 December 2020. Retrieved 9 December 2020.

- ^ Heidenrich, John G. (1993). "The Gulf War: How Many Iraqis Died?". Foreign Policy (90): 108–125. doi:10.2307/1148946. JSTOR 1148946. Archived from the original on 25 February 2021. Retrieved 9 December 2020.

- ^ "UN Security Council Resolution 687 -1991". www.mideastweb.org. Archived from the original on 2018-05-12. Retrieved 2008-11-11.

- ^ Iraq surveys show 'humanitarian emergency' Archived 2009-08-06 at the Wayback Machine UNICEF Newsline August 12, 1999

- ^ Rubin, Michael (December 2001). "Sanctions on Iraq: A Valid Anti-American Grievance?". Middle East Review of International Affairs. 5 (4): 100–115. Archived from the original on 2012-10-28.

- ^ Spagat, Michael (September 2010). "Truth and death in Iraq under sanctions" (PDF). Significance. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2018-07-11. Retrieved 2012-12-22.

- ^ Dyson, Tim; Cetorelli, Valeria (2017-07-01). "Changing views on child mortality and economic sanctions in Iraq: a history of lies, damned lies and statistics". BMJ Global Health. 2 (2): e000311. doi:10.1136/bmjgh-2017-000311. ISSN 2059-7908. PMC 5717930. PMID 29225933.

- ^ "Saddam Hussein said sanctions killed 500,000 children. That was 'a spectacular lie.'". Washington Post. Archived from the original on 2017-08-04. Retrieved 2017-08-04.

- ^ Richard Butler, Saddam Defiant, Weidenfeld & Nicolson, London, 2000, p. 224

- ^ Timeline–Rise, fall and spread of the Islamic State, archived from the original on February 8, 2021, retrieved December 14, 2020

- ^ Gordon, Michael R.; Mazzetti, Mark; Shanker, Thom (17 August 2006). "Bombs Aimed at G.I.'s in Iraq Are Increasing". nytimes.com. Archived from the original on 16 July 2014. Retrieved 27 March 2014.

- ^ Ibrahim, Ellen Knickmeyer and K. I. (23 February 2006). "Bombing Shatters Mosque In Iraq". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on 14 February 2011. Retrieved 3 December 2017.

- ^ Logan, Joseph (December 18, 2011). "Last U.S. troops leave Iraq, ending war". Reuters. Archived from the original on 2017-05-25. Retrieved 2014-08-12.

- ^ "John Kerry holds talks in Iraq as more cities fall to ISIS militants". CNN. 23 June 2014. Archived from the original on 19 January 2016. Retrieved 14 June 2015.

- ^ "Al Qaeda-linked militants capture Fallujah during violent outbreak". Fox News. 4 January 2014. Archived from the original on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 14 June 2015.

- ^ "Militants kill 21 Iraqi leaders, capture 2 border crossings". NY Daily News. 22 June 2014. Archived from the original on 27 December 2014. Retrieved 14 October 2014.

- ^ "Isis seizes Ramadi". The Independent. May 18, 2015. Archived from the original on September 25, 2015. Retrieved December 3, 2017.

- ^ "Iraq: Shiite Gov't faces Mammoth Task in taking Sunni al-Anbar from ISIL". Informed Comment. 19 April 2015. Archived from the original on 13 June 2015. Retrieved 11 June 2015.

- ^ "Islamic State overruns Camp Speicher, routs Iraqi forces". Long War Journal. 19 July 2014. Archived from the original on 26 March 2015. Retrieved 14 October 2014.

- ^ "Insurgents in Iraq Overrun Mosul Provincial Government Headquarters". Voanews.com. Reuters. 2014-06-09. Archived from the original on 2015-12-26. Retrieved 2014-07-31. "Iraqi city of Mosul falls to jihadists". CBS. 10 June 2014. Archived from the original on 18 December 2020. Retrieved 14 June 2015.

- ^ Mostafa, Nehal (9 December 2017). "Iraq announces end of war against IS, liberation of borders with Syria: Abadi". Iraqi News. Archived from the original on 9 December 2017. Retrieved 9 December 2017.

- ^ "Thousands of protesters storm Iraq parliament green zone". AFP. 16 January 2012. Archived from the original on 1 May 2016. Retrieved 30 August 2018.

- ^ "Violence in Iraq at Lowest Level in 10 years". Archived from the original on 22 August 2018. Retrieved 9 September 2018.

- ^ Alkhshali, Hamdi; Tawfeeq, Mohammed; Qiblawi, Tamara (5 October 2019). "Iraq Prime Minister calls protesters' demands 'righteous,' as 93 killed in demonstrations". CNN. Archived from the original on 27 October 2019. Retrieved 5 October 2019.

- ^ "Iraq PM says his would-be assassins have been identified". BBC News. 8 November 2021. Archived from the original on 19 November 2021. Retrieved 24 December 2021.

- ^ "Iraq's Surprise Election Results". Crisis Group. 16 November 2021. Archived from the original on 13 March 2022. Retrieved 27 December 2021.

- ^ "Iraqi leaders vow to move ahead after dozens quit parliament". The Independent. 2022-06-13. Archived from the original on 2022-06-13. Retrieved 2022-06-13.

- ^ National, The (14 October 2022). "Who are Iraq's new president Abdul Latif Rashid and PM nominee Mohammed Shia Al Sudani?". The National. Archived from the original on 17 January 2023. Retrieved 25 October 2022.

- ^ "Iraq gets a new government after a year of deadlock – DW – 10/28/2022". dw.com. Archived from the original on 2023-02-10. Retrieved 2022-10-31.

Sources

[edit]- Aberbach, David (2003). Major Turning Points in Jewish Intellectual History. New York: Palgrave MacMillan. ISBN 978-1403917669.

- Düring, Bleda S. (2020). The Imperialisation of Assyria: An Archaeological Approach. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1108478748.

- Masalha, N. (October 1991). "Faisal's Pan-Arabism, 1921-33". Middle Eastern Studies. Vol. 27, no. 4. pp. 679–693. ISSN 0026-3206. JSTOR 4283470.

Further reading

[edit]- Broich, John. Blood, Oil and the Axis: The Allied Resistance Against a Fascist State in Iraq and the Levant, 1941 (Abrams, 2019).

- de Gaury, Gerald. Three Kings in Baghdad: The Tragedy of Iraq's Monarchy, (IB Taurus, 2008). ISBN 978-1-84511-535-7

- Elliot, Matthew. Independent Iraq: British Influence from 1941 to 1958 (IB Tauris, 1996).

- Fattah, Hala Mundhir, and Frank Caso. A brief history of Iraq (Infobase Publishing, 2009).

- Franzén, Johan. "Development vs. Reform: Attempts at Modernisation during the Twilight of British Influence in Iraq, 1946–1958," Journal of Imperial and Commonwealth History 37#1 (2009), pp. 77–98

- Kriwaczek, Paul. Babylon: Mesopotamia and the Birth of Civilization. Atlantic Books (2010). ISBN 978-1-84887-157-1

- Murray, Williamson, and Kevin M. Woods. The Iran-Iraq War: A military and strategic history (Cambridge UP, 2014).

- Roux, Georges. Ancient Iraq. Penguin Books (1992). ISBN 0-14-012523-X

- Silverfarb, Daniel. Britain's informal empire in the Middle East: a case study of Iraq, 1929-1941 ( Oxford University Press, 1986).

- Silverfarb, Daniel. The twilight of British ascendancy in the Middle East: a case study of Iraq, 1941-1950 (1994)

- Silverfarb, Daniel. "The revision of Iraq's oil concession, 1949–52." Middle Eastern Studies 32.1 (1996): 69-95.

- Simons, Geoff. Iraq: From Sumer to Saddam (Springer, 2016).

- Tarbush, Mohammad A. The role of the military in politics: A case study of Iraq to 1941 (Routledge, 2015).

- Tripp, Charles R. H. (2007). A History of Iraq 3rd edition. Cambridge University Press.

Historiography

[edit]- Bashkin, Orit (2015). "Deconstructing Destruction: The Second Gulf War and the New Historiography of Twentieth-Century Iraq". The Arab Studies Journal. 23 (1): 210–234. ISSN 1083-4753. JSTOR 44744905.