Interstate Highway System

| Dwight D. Eisenhower National System of Interstate and Defense Highways | |

|---|---|

Highway shields for Interstate 80, Business Loop Interstate 80, and the Eisenhower Interstate System

| |

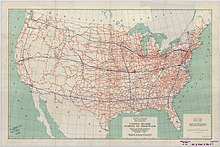

Primary Interstate Highways in the 48 contiguous states. Alaska, Hawaii, and Puerto Rico also have Interstate Highways. | |

| System information | |

| Length | 48,890 mi[a] (78,680 km) |

| Formed | June 29, 1956[1] |

| Highway names | |

| Interstates | Interstate X (I-X) |

| System links | |

| ||

|---|---|---|

|

World War II

34th President of the United States

First Term

Second Term

Presidential campaigns Post-Presidency

|

||

The Dwight D. Eisenhower National System of Interstate and Defense Highways, commonly known as the Interstate Highway System, or the Eisenhower Interstate System, is a network of controlled-access highways that forms part of the National Highway System in the United States. The system extends throughout the contiguous United States and has routes in Hawaii, Alaska, and Puerto Rico.

In the 20th century, the United States Congress began funding roadways through the Federal Aid Road Act of 1916, and started an effort to construct a national road grid with the passage of the Federal Aid Highway Act of 1921. In 1926, the United States Numbered Highway System was established, creating the first national road numbering system for cross-country travel. The roads were state-funded and maintained, and there were few national standards for road design. United States Numbered Highways ranged from two-lane country roads to multi-lane freeways. After Dwight D. Eisenhower became president in 1953, his administration developed a proposal for an interstate highway system, eventually resulting in the enactment of the Federal-Aid Highway Act of 1956.

Unlike the earlier United States Numbered Highway System, the interstates were designed to be all freeways, with nationally unified standards for construction and signage. While some older freeways were adopted into the system, most of the routes were completely new. In dense urban areas, the choice of routing destroyed many well-established neighborhoods, often intentionally as part of a program of "urban renewal".[3] In the two decades following the 1956 Highway Act, the construction of the freeways displaced one million people,[4] and as a result of the many freeway revolts during this era, several planned Interstates were abandoned or re-routed to avoid urban cores.

Construction of the original Interstate Highway System was proclaimed complete in 1992, despite deviations from the original 1956 plan and several stretches that did not fully conform with federal standards. The construction of the Interstate Highway System cost approximately $114 billion (equivalent to $618 billion in 2023). The system has continued to expand and grow as additional federal funding has provided for new routes to be added, and many future Interstate Highways are currently either being planned or under construction.

Though heavily funded by the federal government, Interstate Highways are owned by the state in which they were built. With few exceptions, all Interstates must meet specific standards, such as having controlled access, physical barriers or median strips between lanes of oncoming traffic, breakdown lanes, avoiding at-grade intersections, no traffic lights, and complying with federal traffic sign specifications. Interstate Highways use a numbering scheme in which primary Interstates are assigned one- or two-digit numbers, and shorter routes which branch off of longer ones are assigned three-digit numbers where the last two digits match the parent route. The Interstate Highway System is partially financed through the Highway Trust Fund, which itself is funded by a combination of a federal fuel tax and transfers from the Treasury's general fund.[5] Though federal legislation initially banned the collection of tolls, some Interstate routes are toll roads, either because they were grandfathered into the system or because subsequent legislation has allowed for tolling of Interstates in some cases.

As of 2022[update], about one quarter of all vehicle miles driven in the country used the Interstate Highway System,[6] which has a total length of 48,890 miles (78,680 km).[2] In 2022 and 2023, the number of fatalities on the Interstate Highway System amounted to more than 5,000 people annually, with nearly 5,600 fatalities in 2022.[7]

History

[edit]Planning

[edit]

The United States government's efforts to construct a national network of highways began on an ad hoc basis with the passage of the Federal Aid Road Act of 1916, which provided $75 million over a five-year period for matching funds to the states for the construction and improvement of highways.[8] The nation's revenue needs associated with World War I prevented any significant implementation of this policy, which expired in 1921.

In December 1918, E. J. Mehren, a civil engineer and the editor of Engineering News-Record, presented his "A Suggested National Highway Policy and Plan"[9] during a gathering of the State Highway Officials and Highway Industries Association at the Congress Hotel in Chicago.[10] In the plan, Mehren proposed a 50,000-mile (80,000 km) system, consisting of five east–west routes and 10 north–south routes. The system would include two percent of all roads and would pass through every state at a cost of $25,000 per mile ($16,000/km), providing commercial as well as military transport benefits.[9]

In 1919, the US Army sent an expedition across the US to determine the difficulties that military vehicles would have on a cross-country trip. Leaving from the Ellipse near the White House on July 7, the Motor Transport Corps convoy needed 62 days to drive 3,200 miles (5,100 km) on the Lincoln Highway to the Presidio of San Francisco along the Golden Gate. The convoy suffered many setbacks and problems on the route, such as poor-quality bridges, broken crankshafts, and engines clogged with desert sand.[11]

Dwight Eisenhower, then a 28-year-old brevet lieutenant colonel,[12] accompanied the trip "through darkest America with truck and tank," as he later described it. Some roads in the West were a "succession of dust, ruts, pits, and holes."[11]

As the landmark 1916 law expired, new legislation was passed—the Federal Aid Highway Act of 1921 (Phipps Act). This new road construction initiative once again provided for federal matching funds for road construction and improvement, $75 million allocated annually.[13] Moreover, this new legislation for the first time sought to target these funds to the construction of a national road grid of interconnected "primary highways", setting up cooperation among the various state highway planning boards.[13]

The Bureau of Public Roads asked the Army to provide a list of roads that it considered necessary for national defense.[14] In 1922, General John J. Pershing, former head of the American Expeditionary Force in Europe during the war, complied by submitting a detailed network of 20,000 miles (32,000 km) of interconnected primary highways—the so-called Pershing Map.[15]

A boom in road construction followed throughout the decade of the 1920s, with such projects as the New York parkway system constructed as part of a new national highway system. As automobile traffic increased, planners saw a need for such an interconnected national system to supplement the existing, largely non-freeway, United States Numbered Highways system. By the late 1930s, planning had expanded to a system of new superhighways.

In 1938, President Franklin D. Roosevelt gave Thomas MacDonald, chief at the Bureau of Public Roads, a hand-drawn map of the United States marked with eight superhighway corridors for study.[16] In 1939, Bureau of Public Roads Division of Information chief Herbert S. Fairbank wrote a report called Toll Roads and Free Roads, "the first formal description of what became the Interstate Highway System" and, in 1944, the similarly themed Interregional Highways.[17]

Federal Aid Highway Act of 1956

[edit]The Interstate Highway System gained a champion in President Dwight D. Eisenhower, who was influenced by his experiences as a young Army officer crossing the country in the 1919 Motor Transport Corps convoy that drove in part on the Lincoln Highway, the first road across America. He recalled that, "The old convoy had started me thinking about good two-lane highways... the wisdom of broader ribbons across our land."[11] Eisenhower also gained an appreciation of the Reichsautobahn system, the first "national" implementation of modern Germany's Autobahn network, as a necessary component of a national defense system while he was serving as Supreme Commander of Allied Forces in Europe during World War II.[18] In 1954, Eisenhower appointed General Lucius D. Clay to head a committee charged with proposing an interstate highway system plan.[19] Summing up motivations for the construction of such a system, Clay stated,

It was evident we needed better highways. We needed them for safety, to accommodate more automobiles. We needed them for defense purposes, if that should ever be necessary. And we needed them for the economy. Not just as a public works measure, but for future growth.[20]

Clay's committee proposed a 10-year, $100 billion program ($1.13 trillion in 2023), which would build 40,000 miles (64,000 km) of divided highways linking all American cities with a population of greater than 50,000. Eisenhower initially preferred a system consisting of toll roads, but Clay convinced Eisenhower that toll roads were not feasible outside of the highly populated coastal regions. In February 1955, Eisenhower forwarded Clay's proposal to Congress. The bill quickly won approval in the Senate, but House Democrats objected to the use of public bonds as the means to finance construction. Eisenhower and the House Democrats agreed to instead finance the system through the Highway Trust Fund, which itself would be funded by a gasoline tax.[21] In June 1956, Eisenhower signed the Federal Aid Highway Act of 1956 into law. Under the act, the federal government would pay for 90 percent of the cost of construction of Interstate Highways. Each Interstate Highway was required to be a freeway with at least four lanes and no at-grade crossings.[22]

The publication in 1955 of the General Location of National System of Interstate Highways, informally known as the Yellow Book, mapped out what became the Interstate Highway System.[23] Assisting in the planning was Charles Erwin Wilson, who was still head of General Motors when President Eisenhower selected him as Secretary of Defense in January 1953.

Construction

[edit]

Some sections of highways that became part of the Interstate Highway System actually began construction earlier.

Three states have claimed the title of first Interstate Highway. Missouri claims that the first three contracts under the new program were signed in Missouri on August 2, 1956. The first contract signed was for upgrading a section of US Route 66 to what is now designated Interstate 44.[24] On August 13, 1956, work began on US 40 (now I-70) in St. Charles County.[25][24]

Kansas claims that it was the first to start paving after the act was signed. Preliminary construction had taken place before the act was signed, and paving started September 26, 1956. The state marked its portion of I-70 as the first project in the United States completed under the provisions of the new Federal-Aid Highway Act of 1956.[24]

The Pennsylvania Turnpike could also be considered one of the first Interstate Highways, and is nicknamed "Grandfather of the Interstate System".[25] On October 1, 1940, 162 miles (261 km) of the highway now designated I‑70 and I‑76 opened between Irwin and Carlisle. The Commonwealth of Pennsylvania refers to the turnpike as the Granddaddy of the Pikes, a reference to turnpikes.[24]

Milestones in the construction of the Interstate Highway System include:

- October 17, 1974: Nebraska becomes the first state to complete all of its mainline Interstate Highways with the dedication of its final piece of I-80.[26]

- October 12, 1979: The final section of the Canada to Mexico freeway Interstate 5 is dedicated near Stockton, California. Representatives of the two neighboring nations attended the dedication to commemorate the first contiguous freeway connecting the North American countries.[27]

- August 22, 1986: The final section of the coast-to-coast I-80 (San Francisco, California, to Teaneck, New Jersey) is dedicated on the western edge of Salt Lake City, Utah, making I-80 the world's first contiguous freeway to span from the Atlantic to Pacific Ocean and, at the time, the longest contiguous freeway in the world. The section spanned from Redwood Road to just west of the Salt Lake City International Airport. At the dedication it was noted that coincidentally this was only 50 miles (80 km) from Promontory Summit, where a similar feat was accomplished nearly 120 years prior, the driving of the golden spike of the United States' First transcontinental railroad.[28][29][30]

- August 10, 1990: The final section of coast-to-coast I-10 (Santa Monica, California, to Jacksonville, Florida) is dedicated, the Papago Freeway Tunnel under downtown Phoenix, Arizona. Completion of this section was delayed due to a freeway revolt that forced the cancellation of an originally planned elevated routing.[31]

- September 12, 1991: I-90 becomes the final coast-to-coast Interstate Highway (Seattle, Washington to Boston, Massachusetts) to be completed with the dedication of an elevated viaduct bypassing Wallace, Idaho, which opened a week earlier.[32][33] This section was delayed after residents forced the cancellation of the originally planned at-grade alignment that would have demolished much of downtown Wallace. The residents accomplished this feat by arranging for most of the downtown area to be declared a historic district and listed on the National Register of Historic Places; this succeeded in blocking the path of the original alignment. Two days after the dedication residents held a mock funeral celebrating the removal of the last stoplight on a transcontinental Interstate Highway.[31][34]

- October 14, 1992: The original Interstate Highway System is proclaimed to be complete with the opening of I-70 through Glenwood Canyon in Colorado. This section is considered an engineering marvel with a 12-mile (19 km) span featuring 40 bridges and numerous tunnels and is one of the most expensive rural highways per mile built in the United States.[35][36]

The initial cost estimate for the system was $25 billion over 12 years; it ended up costing $114 billion (equivalent to $425 billion in 2006[37] or $618 billion in 2023[38]) and took 35 years.[39]

1992–present

[edit]Discontinuities

[edit]

The system was proclaimed complete in 1992, but two of the original Interstates—I-95 and I-70—were not continuous: both of these discontinuities were due to local opposition, which blocked efforts to build the necessary connections to fully complete the system. I-95 was made a continuous freeway in 2018,[40] and thus I-70 remains the only original Interstate with a discontinuity.

I-95 was discontinuous in New Jersey because of the cancellation of the Somerset Freeway. This situation was remedied when the construction of the Pennsylvania Turnpike/Interstate 95 Interchange Project started in 2010[41] and partially opened on September 22, 2018, which was already enough to fill the gap.[40]

However, I-70 remains discontinuous in Pennsylvania, because of the lack of a direct interchange with the Pennsylvania Turnpike at the eastern end of the concurrency near Breezewood. Traveling in either direction, I-70 traffic must exit the freeway and use a short stretch of US 30 (which includes a number of roadside services) to rejoin I-70. The interchange was not originally built because of a legacy federal funding rule, since relaxed, which restricted the use of federal funds to improve roads financed with tolls.[42] Solutions have been proposed to eliminate the discontinuity, but they have been blocked by local opposition, fearing a loss of business.[43]

Expansions and removals

[edit]The Interstate Highway System has been expanded numerous times. The expansions have both created new designations and extended existing designations. For example, I-49, added to the system in the 1980s as a freeway in Louisiana, was designated as an expansion corridor, and FHWA approved the expanded route north from Lafayette, Louisiana, to Kansas City, Missouri. The freeway exists today as separate completed segments, with segments under construction or in the planning phase between them.[44]

In 1966, the FHWA designated the entire Interstate Highway System as part of the larger Pan-American Highway System,[45] and at least two proposed Interstate expansions were initiated to help trade with Canada and Mexico spurred by the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA). Long-term plans for I-69, which currently exists in several separate completed segments (the largest of which are in Indiana and Texas), is to have the highway route extend from Tamaulipas, Mexico to Ontario, Canada. The planned I-11 will then bridge the Interstate gap between Phoenix, Arizona and Las Vegas, Nevada, and thus form part of the CANAMEX Corridor (along with I-19, and portions of I-10 and I-15) between Sonora, Mexico and Alberta, Canada.

Opposition, cancellations, and removals

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (March 2015) |

Political opposition from residents canceled many freeway projects around the United States, including:

- I-40 in Memphis, Tennessee was rerouted and part of the original I-40 is still in use as the eastern half of Sam Cooper Boulevard.[47]

- I-66 in the District of Columbia was abandoned in 1977.

- I-69 was to continue past its terminus at Interstate 465 to intersect with Interstate 70 and Interstate 65 at the north split, northeast of downtown Indianapolis. Though local opposition led to the cancellation of this project in 1981, bridges and ramps for the connection into the "north split" remained until it was rebuilt in 2023.

- I-70 in Baltimore was supposed to run from the Baltimore Beltway (Interstate 695), which surrounds the city to terminate at I-95, the East Coast thoroughfare that runs through Maryland and Baltimore on a diagonal course, northeast to southwest; the connection was cancelled on the mid-1970s due to its routing through Gwynns Falls-Leakin Park, a wilderness urban park reserve following the Gwynns Falls stream through West Baltimore. This included the cancellation of I-170, partially built and in use as US 40, and nicknamed the Highway to Nowhere. The freeway stub of I-70 inside the Beltway was renumbered MD 570 in 2014, but continues to bear I-70 signs.

- I-78 in New York City was canceled along with portions of I-278, I-478, and I-878. I-878 was supposed to be part of I-78, and I-478 and I-278 were to be spur routes.

- I-80 in San Francisco was originally planned to travel past the city's Civic Center along the Panhandle Freeway into Golden Gate Park and terminate at the original alignment of I-280/SR 1. The city canceled this and several other freeways in 1958. Similarly, more than 20 years later, Sacramento canceled plans to upgrade I-80 to Interstate Standards and rerouted the freeway on what was then I-880 that traveled north of Downtown Sacramento.

- I-83, southern extension of the Jones Falls Expressway (southern I-83) in Baltimore was supposed to run along the waterfront of the Patapsco River / Baltimore Harbor to connect to I-95, bisecting historic neighborhoods of Fells Point and Canton, but the connection was never built.

- I-84 in Connecticut was once planned to fork east of Hartford, into an I-86 to Sturbridge, Massachusetts, and I-84 to Providence, R.I. The plan was cancelled, primarily because of anticipated impact on a major Rhode Island reservoir. The I-84 designation was restored to the highway to Sturbridge, and other numbering was used for completed Eastern sections of what had been planned as part of I-84.

- I-95 through the District of Columbia into Maryland was abandoned in 1977. Instead it was rerouted to I-495 (Capital Beltway). The completed section is now I-395.

- I-95 was originally planned to run up the Southwest Expressway and meet I-93, where the two highways would travel along the Central Artery through downtown Boston, but was rerouted onto the Route 128 beltway due to widespread opposition. This revolt also included the cancellation of the Inner Belt, connecting I-93 to I-90 and a cancelled section of the Northwest Expressway which would have carried US 3 inside the Route 128 beltway, meeting with Route 2 in Cambridge.

In addition to cancellations, removals of freeways are planned:

- I-81 in Syracuse, New York, which bisects the city's 15th Ward neighborhood, is planned to be torn down and replaced with a boulevard that accommodates pedestrians.[46][48] Freeway traffic would be rerouted along I-481.[48]

Standards

[edit]The American Association of State Highway and Transportation Officials (AASHTO) has defined a set of standards that all new Interstates must meet unless a waiver from the Federal Highway Administration (FHWA) is obtained. One almost absolute standard is the controlled access nature of the roads. With few exceptions, traffic lights (and cross traffic in general) are limited to toll booths and ramp meters (metered flow control for lane merging during rush hour).

Speed limits

[edit]

Being freeways, Interstate Highways usually have the highest speed limits in a given area. Speed limits are determined by individual states. From 1975 to 1986, the maximum speed limit on any highway in the United States was 55 miles per hour (90 km/h), in accordance with federal law.[49]

Typically, lower limits are established in Northeastern and coastal states, while higher speed limits are established in inland states west of the Mississippi River.[50] For example, the maximum speed limit is 75 mph (120 km/h) in northern Maine, varies between 50 and 70 mph (80 and 115 km/h)[51] from southern Maine to New Jersey, and is 50 mph (80 km/h) in New York City and the District of Columbia.[50] Currently, rural speed limits elsewhere generally range from 65 to 80 miles per hour (105 to 130 km/h). Several portions of various highways such as I-10 and I-20 in rural western Texas, I-80 in Nevada between Fernley and Winnemucca (except around Lovelock) and portions of I-15, I-70, I-80, and I-84 in Utah have a speed limit of 80 mph (130 km/h). Other Interstates in Idaho, Montana, Oklahoma, South Dakota and Wyoming also have the same high speed limits.

In some areas, speed limits on Interstates can be significantly lower in areas where they traverse significantly hazardous areas. The maximum speed limit on I-90 is 50 mph (80 km/h) in downtown Cleveland because of two sharp curves with a suggested limit of 35 mph (55 km/h) in a heavily congested area; I-70 through Wheeling, West Virginia, has a maximum speed limit of 45 mph (70 km/h) through the Wheeling Tunnel and most of downtown Wheeling; and I-68 has a maximum speed limit of 40 mph (65 km/h) through Cumberland, Maryland, because of multiple hazards including sharp curves and narrow lanes through the city. In some locations, low speed limits are the result of lawsuits and resident demands; after holding up the completion of I-35E in St. Paul, Minnesota, for nearly 30 years in the courts, residents along the stretch of the freeway from the southern city limit to downtown successfully lobbied for a 45 mph (70 km/h) speed limit in addition to a prohibition on any vehicle weighing more than 9,000 pounds (4,100 kg) gross vehicle weight. I-93 in Franconia Notch State Park in northern New Hampshire has a speed limit of 45 mph (70 km/h) because it is a parkway that consists of only one lane per side of the highway. On the other hand, Interstates 15, 80, 84, and 215 in Utah have speed limits as high as 70 mph (115 km/h) within the Wasatch Front, Cedar City, and St. George areas, and I-25 in New Mexico within the Santa Fe and Las Vegas areas along with I-20 in Texas along Odessa and Midland and I-29 in North Dakota along the Grand Forks area have higher speed limits of 75 mph (120 km/h).

Other uses

[edit]As one of the components of the National Highway System, Interstate Highways improve the mobility of military troops to and from airports, seaports, rail terminals, and other military bases. Interstate Highways also connect to other roads that are a part of the Strategic Highway Network, a system of roads identified as critical to the US Department of Defense.[52]

The system has also been used to facilitate evacuations in the face of hurricanes and other natural disasters. An option for maximizing traffic throughput on a highway is to reverse the flow of traffic on one side of a divider so that all lanes become outbound lanes. This procedure, known as contraflow lane reversal, has been employed several times for hurricane evacuations. After public outcry regarding the inefficiency of evacuating from southern Louisiana prior to Hurricane Georges' landfall in September 1998, government officials looked towards contraflow to improve evacuation times. In Savannah, Georgia, and Charleston, South Carolina, in 1999, lanes of I-16 and I-26 were used in a contraflow configuration in anticipation of Hurricane Floyd with mixed results.[53]

In 2004, contraflow was employed ahead of Hurricane Charley in the Tampa, Florida area and on the Gulf Coast before the landfall of Hurricane Ivan;[54] however, evacuation times there were no better than previous evacuation operations. Engineers began to apply lessons learned from the analysis of prior contraflow operations, including limiting exits, removing troopers (to keep traffic flowing instead of having drivers stop for directions), and improving the dissemination of public information. As a result, the 2005 evacuation of New Orleans, Louisiana, prior to Hurricane Katrina ran much more smoothly.[55]

According to urban legend, early regulations required that one out of every five miles of the Interstate Highway System must be built straight and flat, so as to be usable by aircraft during times of war. There is no evidence of this rule being included in any Interstate legislation.[56][57] It is also commonly believed the Interstate Highway System was built for the sole purpose of evacuating cities in the event of nuclear warfare. While military motivations were present, the primary motivations were civilian.[58][59]

Numbering system

[edit]Primary (one- and two-digit) Interstates

[edit]

The numbering scheme for the Interstate Highway System was developed in 1957 by the American Association of State Highway and Transportation Officials (AASHTO). The association's present numbering policy dates back to August 10, 1973.[60] Within the contiguous United States, primary Interstates—also called main line Interstates or two-digit Interstates—are assigned numbers less than 100.[60]

While numerous exceptions do exist, there is a general scheme for numbering Interstates. Primary Interstates are assigned one- or two-digit numbers, while shorter routes (such as spurs, loops, and short connecting roads) are assigned three-digit numbers where the last two digits match the parent route (thus, I-294 is a loop that connects at both ends to I-94, while I-787 is a short spur route attached to I-87). In the numbering scheme for the primary routes, east–west highways are assigned even numbers and north–south highways are assigned odd numbers. Odd route numbers increase from west to east, and even-numbered routes increase from south to north (to avoid confusion with the US Highways, which increase from east to west and north to south).[61] This numbering system usually holds true even if the local direction of the route does not match the compass directions. Numbers divisible by five are intended to be major arteries among the primary routes, carrying traffic long distances.[62][63] Primary north–south Interstates increase in number from I-5 between Canada and Mexico along the West Coast to I‑95 between Canada and Miami, Florida along the East Coast. Major west–east arterial Interstates increase in number from I-10 between Santa Monica, California, and Jacksonville, Florida, to I-90 between Seattle, Washington, and Boston, Massachusetts, with two exceptions. There are no I-50 and I-60, as routes with those numbers would likely pass through states that currently have US Highways with the same numbers, which is generally disallowed under highway administration guidelines.[60][64]

Several two-digit numbers are shared between unconnected road segments at opposite ends of the country for various reasons. Some such highways are incomplete Interstates (such as I-69 and I-74) and some just happen to share route designations (such as I-76, I-84, I‑86, I-87, and I-88). Some of these were due to a change in the numbering system as a result of a new policy adopted in 1973. Previously, letter-suffixed numbers were used for long spurs off primary routes; for example, western I‑84 was I‑80N, as it went north from I‑80. The new policy stated, "No new divided numbers (such as I-35W and I-35E, etc.) shall be adopted." The new policy also recommended that existing divided numbers be eliminated as quickly as possible; however, an I-35W and I-35E still exist in the Dallas–Fort Worth metroplex in Texas, and an I-35W and I-35E that run through Minneapolis and Saint Paul, Minnesota, still exist.[60] Additionally, due to Congressional requirements, three sections of I-69 in southern Texas will be divided into I-69W, I-69E, and I-69C (for Central).[65]

AASHTO policy allows dual numbering to provide continuity between major control points.[60] This is referred to as a concurrency or overlap. For example, I‑75 and I‑85 share the same roadway in Atlanta; this 7.4-mile (11.9 km) section, called the Downtown Connector, is labeled both I‑75 and I‑85. Concurrencies between Interstate and US Highway numbers are also allowed in accordance with AASHTO policy, as long as the length of the concurrency is reasonable.[60] In rare instances, two highway designations sharing the same roadway are signed as traveling in opposite directions; one such wrong-way concurrency is found between Wytheville and Fort Chiswell, Virginia, where I‑81 north and I‑77 south are equivalent (with that section of road traveling almost due east), as are I‑81 south and I‑77 north.

Auxiliary (three-digit) Interstates

[edit]

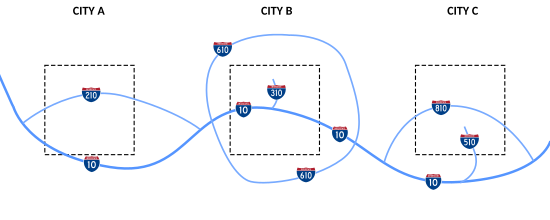

Auxiliary Interstate Highways are circumferential, radial, or spur highways that principally serve urban areas. These types of Interstate Highways are given three-digit route numbers, which consist of a single digit prefixed to the two-digit number of its parent Interstate Highway. Spur routes deviate from their parent and do not return; these are given an odd first digit. Circumferential and radial loop routes return to the parent, and are given an even first digit. Unlike primary Interstates, three-digit Interstates are signed as either east–west or north–south, depending on the general orientation of the route, without regard to the route number. For instance, I-190 in Massachusetts is labeled north–south, while I-195 in New Jersey is labeled east–west. Some looped Interstate routes use inner–outer directions instead of compass directions, when the use of compass directions would create ambiguity. Due to the large number of these routes, auxiliary route numbers may be repeated in different states along the mainline.[66] Some auxiliary highways do not follow these guidelines, however.

Alaska, Hawaii, and Puerto Rico

[edit]

The Interstate Highway System also extends to Alaska, Hawaii, and Puerto Rico, even though they have no direct land connections to any other states or territories. However, their residents still pay federal fuel and tire taxes.

The Interstates in Hawaii, all located on the most populous island of Oahu, carry the prefix H. There are three one-digit routes in the state (H-1, H-2, and H-3) and one auxiliary route (H-201). These Interstates connect several military and naval bases together, as well as the important communities spread across Oahu, and especially within the urban core of Honolulu.

Both Alaska and Puerto Rico also have public highways that receive 90 percent of their funding from the Interstate Highway program. The Interstates of Alaska and Puerto Rico are numbered sequentially in order of funding without regard to the rules on odd and even numbers. They also carry the prefixes A and PR, respectively. However, these highways are signed according to their local designations, not their Interstate Highway numbers. Furthermore, these routes were neither planned according to nor constructed to the official Interstate Highway standards.[67]

Mile markers and exit numbers

[edit]On one- or two-digit Interstates, the mile marker numbering almost always begins at the southern or western state line. If an Interstate originates within a state, the numbering begins from the location where the road begins in the south or west. As with all guidelines for Interstate routes, however, numerous exceptions exist.

Three-digit Interstates with an even first number that form a complete circumferential (circle) bypass around a city feature mile markers that are numbered in a clockwise direction, beginning just west of an Interstate that bisects the circumferential route near a south polar location. In other words, mile marker 1 on I-465, a 53-mile (85 km) route around Indianapolis, is just west of its junction with I-65 on the south side of Indianapolis (on the south leg of I-465), and mile marker 53 is just east of this same junction. An exception is I-495 in the Washington metropolitan area, with mileposts increasing counterclockwise because part of that road is also part of I-95.

Most Interstate Highways use distance-based exit numbers so that the exit number is the same as the nearest mile marker. If multiple exits occur within the same mile, letter suffixes may be appended to the numbers in alphabetical order starting with A.[68] A small number of Interstate Highways (mostly in the Northeastern United States) use sequential-based exit numbering schemes (where each exit is numbered in order starting with 1, without regard for the mile markers on the road). One Interstate Highway, I-19 in Arizona, is signed with kilometer-based exit numbers. In the state of New York, most Interstate Highways use sequential exit numbering, with some exceptions.[69]

Business routes

[edit]AASHTO defines a category of special routes separate from primary and auxiliary Interstate designations. These routes do not have to comply to Interstate construction or limited-access standards but are routes that may be identified and approved by the association. The same route marking policy applies to both US Numbered Highways and Interstate Highways; however, business route designations are sometimes used for Interstate Highways.[70] Known as Business Loops and Business Spurs, these routes principally travel through the corporate limits of a city, passing through the central business district when the regular route is directed around the city. They also use a green shield instead of the red and blue shield.[70] An example would be Business Loop Interstate 75 at Pontiac, Michigan, which follows surface roads into and through downtown. Sections of BL I-75's routing had been part of US 10 and M-24, predecessors of I-75 in the area.

Financing

[edit]

Interstate Highways and their rights-of-way are owned by the state in which they were built. The last federally owned portion of the Interstate System was the Woodrow Wilson Bridge on the Washington Capital Beltway. The new bridge was completed in 2009 and is collectively owned by Virginia and Maryland.[71] Maintenance is generally the responsibility of the state department of transportation. However, there are some segments of Interstate owned and maintained by local authorities.

Taxes and user fees

[edit]About 70 percent of the construction and maintenance costs of Interstate Highways in the United States have been paid through user fees, primarily the fuel taxes collected by the federal, state, and local governments. To a much lesser extent they have been paid for by tolls collected on toll highways and bridges. The federal gasoline tax was first imposed in 1932 at one cent per gallon; during the Eisenhower administration, the Highway Trust Fund, established by the Highway Revenue Act in 1956, prescribed a three-cent-per-gallon fuel tax, soon increased to 4.5 cents per gallon. Since 1993 the tax has remained at 18.4 cents per gallon.[72] Other excise taxes related to highway travel also accumulated in the Highway Trust Fund.[72] Initially, that fund was sufficient for the federal portion of building the Interstate system, built in the early years with "10 cent dollars", from the perspective of the states, as the federal government paid 90% of the costs while the state paid 10%. The system grew more rapidly than the rate of the taxes on fuel and other aspects of driving (e. g., excise tax on tires).

The rest of the costs of these highways are borne by general fund receipts, bond issues, designated property taxes, and other taxes. The federal contribution is funded primarily through fuel taxes and through transfers from the Treasury's general fund.[5] Local government contributions are overwhelmingly from sources besides user fees.[73] As decades passed in the 20th century and into the 21st century, the portion of the user fees spent on highways themselves covers about 57 percent of their costs, with about one-sixth of the user fees being sent to other programs, including the mass transit systems in large cities. Some large sections of Interstate Highways that were planned or constructed before 1956 are still operated as toll roads, for example the Massachusetts Turnpike (I-90), the New York State Thruway (I-87 and I-90), and Kansas Turnpike (I-35, I-335, I-470, I-70). Others have had their construction bonds paid off and they have become toll-free, such as the Connecticut Turnpike (I‑95, I-395), the Richmond-Petersburg Turnpike in Virginia (also I‑95), and the Kentucky Turnpike (I‑65).

As American suburbs have expanded, the costs incurred in maintaining freeway infrastructure have also grown, leaving little in the way of funds for new Interstate construction.[74] This has led to the proliferation of toll roads (turnpikes) as the new method of building limited-access highways in suburban areas. Some Interstates are privately maintained (for example, the VMS company maintains I‑35 in Texas)[75] to meet rising costs of maintenance and allow state departments of transportation to focus on serving the fastest-growing regions in their states.

Parts of the Interstate System might have to be tolled in the future to meet maintenance and expansion demands, as has been done with adding toll HOV/HOT lanes in cities such as Atlanta, Dallas, and Los Angeles. Although part of the tolling is an effect of the SAFETEA‑LU act, which has put an emphasis on toll roads as a means to reduce congestion,[76][77] present federal law does not allow for a state to change a freeway section to a tolled section for all traffic.[citation needed]

Tolls

[edit]

About 2,900 miles (4,700 km) of toll roads are included in the Interstate Highway System.[78] While federal legislation initially banned the collection of tolls on Interstates, many of the toll roads on the system were either completed or under construction when the Interstate Highway System was established. Since these highways provided logical connections to other parts of the system, they were designated as Interstate highways. Congress also decided that it was too costly to either build toll-free Interstates parallel to these toll roads, or directly repay all the bondholders who financed these facilities and remove the tolls. Thus, these toll roads were grandfathered into the Interstate Highway System.[79]

Toll roads designated as Interstates (such as the Massachusetts Turnpike) were typically allowed to continue collecting tolls, but are generally ineligible to receive federal funds for maintenance and improvements. Some toll roads that did receive federal funds to finance emergency repairs (notably the Connecticut Turnpike (I-95) following the Mianus River Bridge collapse) were required to remove tolls as soon as the highway's construction bonds were paid off. In addition, these toll facilities were grandfathered from Interstate Highway standards. A notable example is the western approach to the Benjamin Franklin Bridge in Philadelphia, where I-676 has a surface street section through a historic area.

Policies on toll facilities and Interstate Highways have since changed. The Federal Highway Administration has allowed some states to collect tolls on existing Interstate Highways, while a recent extension of I-376 included a section of Pennsylvania Route 60 that was tolled by the Pennsylvania Turnpike Commission before receiving Interstate designation. Also, newer toll facilities (like the tolled section of I-376, which was built in the early 1990s) must conform to Interstate standards. A new addition of the Manual on Uniform Traffic Control Devices in 2009 requires a black-on-yellow "Toll" sign to be placed above the Interstate trailblazer on Interstate Highways that collect tolls.[80]

Legislation passed in 2005 known as SAFETEA-LU, encouraged states to construct new Interstate Highways through "innovative financing" methods. SAFETEA-LU facilitated states to pursue innovative financing by easing the restrictions on building interstates as toll roads, either through state agencies or through public–private partnerships. However, SAFETEA-LU left in place a prohibition of installing tolls on existing toll-free Interstates, and states wishing to toll such routes to finance upgrades and repairs must first seek approval from Congress. Many states have started using High-occupancy toll lane and other partial tolling methods, whereby certain lanes of highly congested freeways are tolled, while others are left free, allowing people to pay a fee to travel in less congested lanes. Examples of recent projects to add HOT lanes to existing freeways include the Virginia HOT lanes on the Virginia portions of the Capital Beltway and other related interstate highways (I-95, I-495, I-395) and the addition of express toll lanes to Interstate 77 in North Carolina in the Charlotte metropolitan area.

Chargeable and non-chargeable Interstate routes

[edit]Interstate Highways financed with federal funds are known as "chargeable" Interstate routes, and are considered part of the 42,000-mile (68,000 km) network of highways. Federal laws also allow "non-chargeable" Interstate routes, highways funded similarly to state and US Highways to be signed as Interstates, if they both meet the Interstate Highway standards and are logical additions or connections to the system.[81][82] These additions fall under two categories: routes that already meet Interstate standards, and routes not yet upgraded to Interstate standards. Only routes that meet Interstate standards may be signed as Interstates once their proposed number is approved.[67]

Signage

[edit]Interstate shield

[edit]

Interstate Highways are signed by a number placed on a red, white, and blue sign. The shield design itself is a registered trademark of the American Association of State Highway and Transportation Officials.[83] The colors red, white, and blue were chosen because they are the colors of the American flag. In the original design, the name of the state was displayed above the highway number, but in many states, this area is now left blank, allowing for the printing of larger and more-legible digits. Signs with the shield alone are placed periodically throughout each Interstate as reassurance markers. These signs usually measure 36 inches (91 cm) high, and are 36 inches (91 cm) wide for two-digit Interstates or 45 inches (110 cm) for three-digit Interstates.[84]

Interstate business loops and spurs use a special shield in which the red and blue are replaced with green, the word "BUSINESS" appears instead of "INTERSTATE", and the word "SPUR" or "LOOP" usually appears above the number.[84] The green shield is employed to mark the main route through a city's central business district, which intersects the associated Interstate at one (spur) or both (loop) ends of the business route. The route usually traverses the main thoroughfare(s) of the city's downtown area or other major business district.[85] A city may have more than one Interstate-derived business route, depending on the number of Interstates passing through a city and the number of significant business districts therein.[86]

Over time, the design of the Interstate shield has changed. In 1957 the Interstate shield designed by Texas Highway Department employee Richard Oliver was introduced, the winner of a contest that included 100 entries;[87][88] at the time, the shield color was a dark navy blue and only 17 inches (43 cm) wide.[89] The Manual on Uniform Traffic Control Devices (MUTCD) standards revised the shield in the 1961,[90] 1971,[91] and 1978[92] editions.

Exit numbering

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (June 2011) |

The majority of Interstates have exit numbers. Like other highways, Interstates feature guide signs that list control cities to help direct drivers through interchanges and exits toward their desired destination. All traffic signs and lane markings on the Interstates are supposed to be designed in compliance with the Manual on Uniform Traffic Control Devices (MUTCD). There are, however, many local and regional variations in signage.

For many years, California was the only state that did not use an exit numbering system. It was granted an exemption in the 1950s due to having an already largely completed and signed highway system; placing exit number signage across the state was deemed too expensive. To control costs, California began to incorporate exit numbers on its freeways in 2002—Interstate, US, and state routes alike. Caltrans commonly installs exit number signage only when a freeway or interchange is built, reconstructed, retrofitted, or repaired, and it is usually tacked onto the top-right corner of an already existing sign. Newer signs along the freeways follow this practice as well. Most exits along California's Interstates now have exit number signage, particularly in rural areas. California, however, still does not use mileposts, although a few exist for experiments or for special purposes.[93][self-published source]

In 2010–2011, the Illinois State Toll Highway Authority posted all new mile markers to be uniform with the rest of the state on I‑90 (Jane Addams Memorial/Northwest Tollway) and the I‑94 section of the Tri‑State Tollway, which previously had matched the I‑294 section starting in the south at I‑80/I‑94/IL Route 394. This also applied to the tolled portion of the Ronald Reagan Tollway (I-88). The tollway also added exit number tabs to the exits.[citation needed]

Exit numbers correspond to Interstate mileage markers in most states. On I‑19 in Arizona, however, length is measured in kilometers instead of miles because, at the time of construction, a push for the United States to change to a metric system of measurement had gained enough traction that it was mistakenly assumed that all highway measurements would eventually be changed to metric (and some distance signs retain metric distances);[94] proximity to metric-using Mexico may also have been a factor, as I‑19 indirectly connects I‑10 to the Mexican Federal Highway system via surface streets in Nogales. Mileage count increases from west to east on most even-numbered Interstates; on odd-numbered Interstates mileage count increases from south to north.

Some highways, including the New York State Thruway, use sequential exit-numbering schemes. Exits on the New York State Thruway count up from Yonkers traveling north, and then west from Albany. I‑87 in New York State is numbered in three sections. The first section makes up the Major Deegan Expressway in the Bronx, with interchanges numbered sequentially from 1 to 14. The second section of I‑87 is a part of the New York State Thruway that starts in Yonkers (exit 1) and continues north to Albany (exit 24); at Albany, the Thruway turns west and becomes I‑90 for exits 25 to 61. From Albany north to the Canadian border, the exits on I‑87 are numbered sequentially from 1 to 44 along the Adirondack Northway. This often leads to confusion as there is more than one exit on I‑87 with the same number. For example, exit 4 on Thruway section of I‑87 connects with the Cross County Parkway in Yonkers, but exit 4 on the Northway is the exit for the Albany airport. These two exits share a number but are located 150 miles (240 km) apart.

Many northeastern states label exit numbers sequentially, regardless of how many miles have passed between exits. States in which Interstate exits are still numbered sequentially are Connecticut, Delaware, New Hampshire, New York, and Vermont; as such, three of the main Interstate Highways that remain completely within these states (87, 88, 89) have interchanges numbered sequentially along their entire routes. Maine, Massachusetts, Pennsylvania, Virginia, Georgia, and Florida followed this system for a number of years, but have since converted to mileage-based exit numbers. Georgia renumbered in 2000, while Maine did so in 2004. Massachusetts converted its exit numbers in 2021, and most recently Rhode Island in 2022.[95] The Pennsylvania Turnpike uses both mile marker numbers and sequential numbers. Mile marker numbers are used for signage, while sequential numbers are used for numbering interchanges internally. The New Jersey Turnpike, including the portions that are signed as I‑95 and I‑78, also has sequential numbering, but other Interstates within New Jersey use mile markers.

Sign locations

[edit]There are four common signage methods on Interstates:

- Locating a sign on the ground to the side of the highway, mostly the right, and is used to denote exits, as well as rest areas, motorist services such as gas and lodging, recreational sites, and freeway names

- Attaching the sign to an overpass

- Mounting on full gantries that bridge the entire width of the highway and often show two or more signs

- Mounting on half-gantries that are located on one side of the highway, like a ground-mounted sign

Statistics

[edit]

Volume

[edit]Elevation

[edit]- Highest: 11,158 feet (3,401 m): I-70 in the Eisenhower Tunnel at the Continental Divide in the Colorado Rocky Mountains.[97]

- Lowest (land): −52 feet (−16 m): I-8 at the New River near Seeley, California.[97]

- Lowest (underwater): −103 feet (−31 m): I-95 in the Fort McHenry Tunnel under the Baltimore Inner Harbor.[98]

Length

[edit]- Longest (east–west): 3,020.54 miles (4,861.09 km): I-90 from Boston, Massachusetts, to Seattle, Washington.[99][100]

- Longest (north–south): 1,908 mi (3,071 km): I-95 from the Canadian border near Houlton, Maine, to Miami, Florida.[99][40]

- Shortest (two-digit): 1.40 mi (2.25 km): I-69W in Laredo, Texas.[101]

- Shortest (auxiliary): 0.70 mi (1.13 km): I-878 in Queens, New York, New York.[102][103]

- Longest segment between state lines: 877 mi (1,411 km): I-10 in Texas from the New Mexico state line near El Paso to the Louisiana state line near Orange, Texas.[104]

- Shortest segment between state lines: 453 ft (138 m): I-95/I-495 (Capital Beltway) on the Woodrow Wilson Bridge across the Potomac River where they briefly cross the southernmost tip of the District of Columbia between its borders with Maryland and Virginia.[100]

- Longest concurrency: 278.4 mi (448.0 km): I-80 and I-90; Gary, Indiana, to Elyria, Ohio.[105]

States

[edit]- Most states served by an Interstate: 15 states plus the District of Columbia: I-95 through Florida, Georgia, South Carolina, North Carolina, Virginia, DC, Maryland, Delaware, Pennsylvania, New Jersey, New York, Connecticut, Rhode Island, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, and Maine.[99]

- Most Interstates in a state: 32 routes: New York, totaling 1,750.66 mi (2,817.41 km)[106]

- Most primary Interstates in a state: 13 routes: Illinois[b][106]

- Most Interstate mileage in a state: 3,233.45 mi (5,203.73 km): Texas, in 17 different routes.[99]

- Fewest Interstates in a state: 3 routes: Delaware, New Mexico, North Dakota, and Rhode Island. Puerto Rico also has 3 routes.[106]

- Fewest primary Interstates in a state: 1 route: Delaware, Maine, and Rhode Island (I-95 in each case).[106]

- Least Interstate mileage in a state: 40.61 mi (65.36 km): Delaware, in 3 different routes.[106]

Impact and reception

[edit]Following the passage of the Federal Aid Highway Act of 1956, passenger rail declined sharply as did freight rail for a short time, but the trucking industry expanded dramatically and the cost of shipping and travel fell sharply.[107][citation needed] Suburbanization became possible, with the rapid growth of larger, sprawling, and more car-dependent housing than was available in central cities, enabling racial segregation by white flight.[108][109][110] A sense of isolationism developed in suburbs, with suburbanites wanting to keep urban areas disconnected from the suburbs.[108] Tourism dramatically expanded, creating a demand for more service stations, motels, restaurants and visitor attractions. The Interstate System was the basis for urban expansion in the Sun Belt, and many urban areas in the region are thus very car-dependent.[111] The highways may have contributed to increased economic productivity in, and thereby increased migration to, the Sun Belt.[112] In rural areas, towns and small cities off the grid lost out as shoppers followed the interstate and new factories were located near them.[113]

The system had a profound effect on interstate shipping. The Interstate Highway System was being constructed at the same time as the intermodal shipping container made its debut. These containers could be placed on trailers behind trucks and shipped across the country with ease. A new road network and shipping containers that could be easily moved from ship to train to truck, meant that overseas manufacturers and domestic startups could get their products to market quicker than ever, allowing for accelerated economic growth.[114] Forty years after its construction, the Interstate Highway system returned on investment, making $6[among whom?] for every $1 spent on the project.[115] According to research by the FHWA, "from 1950 to 1989, approximately one-quarter of the nation's productivity increase is attributable to increased investment in the highway system."[116]

The system had a particularly strong effect in Southern states, where major highways were inadequate[citation needed]. The new system facilitated the relocation of heavy manufacturing to the South and spurred the development of Southern-based corporations like Walmart (in Arkansas) and FedEx (in Tennessee).[114]

The Interstate Highway System also dramatically affected American culture, contributing to cars becoming more central to the American identity. Before, driving was considered an excursion that required some amount of skill and could have some chance of unpredictability. With the standardization of signs, road widths and rules, certain unpredictabilities lessened. Justin Fox wrote, "By making road more reliable and by making Americans more reliant on them, they took away most of the adventure and romance associated with driving."[114]

The Interstate Highway System has been criticized for contributing to the decline of some cities that were divided by Interstates, and for displacing minority neighborhoods in urban centers.[3] Between 1957 and 1977, the Interstate System alone displaced over 475,000 households and one million people across the country.[4] Highways have also been criticized for increasing racial segregation by creating physical barriers between neighborhoods,[117] and for overall reductions in available housing and population in neighborhoods affected by highway construction.[118] Other critics have blamed the Interstate Highway System for the decline of public transportation in the United States since the 1950s,[119] which minorities and low-income residents are three to six times more likely to use.[120] Previous highways, such as US 66, were also bypassed by the new Interstate system, turning countless rural communities along the way into ghost towns.[121] The Interstate System has also contributed to continued resistance against new public transportation.[108]

The Interstate Highway System had a negative impact on minority groups, especially in urban areas. Even though the government used eminent domain to obtain land for the Interstates, it was still economical to build where land was cheapest. This cheap land was often located in predominately minority areas.[111] Not only were minority neighborhoods destroyed, but in some cities the Interstates were used to divide white and minority neighborhoods.[108] These practices were common in cities both in the North and South, including Nashville, Miami, Chicago, Detroit, and many other cities. The division and destruction of neighborhoods led to the limitation of employment and other opportunities, which deteriorated the economic fabric of neighborhoods.[120] Neighborhoods bordering Interstates have a much higher level of particulate air pollution and are more likely to be chosen for polluting industrial facilities.[120]

See also

[edit]- Highway systems by country

- List of controlled-access highway systems

- Non-motorized access on freeways

Notes

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Weingroff, Richard F. (Summer 1996). "Federal-Aid Highway Act of 1956, Creating the Interstate System". Public Roads. Vol. 60, no. 1. ISSN 0033-3735. Archived from the original on March 7, 2012. Retrieved March 16, 2012.

- ^ a b Office of Highway Policy Information (January 12, 2024). Table HM-20: Public Road Length, 2022, Miles By Functional System (Report). Federal Highway Administration. Retrieved August 14, 2024.

- ^ a b Stromberg, Joseph (May 11, 2016). "Highways Gutted American Cities. So Why Did They Build Them?". Vox. Archived from the original on April 25, 2019. Retrieved May 10, 2019.

- ^ a b Gamboa, Suzanne; McCausland, Phil; Lederman, Josh; Popken, Ben (June 18, 2021). "Bulldozed and bisected: Highway construction built a legacy of inequality". NBC News. Retrieved June 18, 2023.

- ^ a b Shirley, Chad (2023). Testimony on the Status of the Highway Trust Fund: 2023 Update (Report). Congressional Budget Office.

- ^ Office of Highway Policy Information (February 5, 2024). Table VM-1: Annual Vehicle Distance Traveled in Miles and Related Data, 2022, by Highway Category and Vehicle Type (Report). Federal Highway Administration. Retrieved August 14, 2024.

- ^ National Center for Statistics and Analysis (May 2024). Early Estimates of Motor Vehicle Traffic Fatalities and Fatality Rate by Sub-Categories in 2023 (Report). National Highway Traffic Safety Administration. DOT HS 813 581. Retrieved August 14, 2024.

- ^ Schwantes, Carlos Arnaldo (2003). Going Places: Transportation Redefines the Twentieth-Century West. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. p. 142. ISBN 9780253342027.

- ^ a b Mehren, E.J. (December 19, 1918). "A Suggested National Highway Policy and Plan". Engineering News-Record. Vol. 81, no. 25. pp. 1112–1117. ISSN 0891-9526. Retrieved August 17, 2015 – via Google Books.

- ^ Weingroff, Richard (October 15, 2013). "'Clearly Vicious as a Matter of Policy': The Fight Against Federal-Aid". Federal Highway Administration. Archived from the original on September 24, 2015. Retrieved August 17, 2015.

- ^ a b c Watson, Bruce (July–August 2020). "Ike's Excellent Adventure". American Heritage. Vol. 65, no. 4. Archived from the original on July 9, 2020. Retrieved July 9, 2020.

- ^ Ambrose, Stephen (1983). Eisenhower: Soldier, General of the Army, President-Elect (1893–1952). Vol. 1. New York: Simon & Schuster.[page needed]

- ^ a b Schwantes (2003), p. 152.

- ^ McNichol, Dan (2006a). The Roads That Built America: The Incredible Story of the U.S. Interstate System. New York: Sterling. p. 87. ISBN 978-1-4027-3468-7.

- ^ Schwantes (2003), p. 153.

- ^ McNichol (2006a), p. 78.

- ^ Weingroff, Richard F. (Summer 1996). "The Federal-State Partnership at Work: The Concept Man". Public Roads. Vol. 60, no. 1. ISSN 0033-3735. Archived from the original on May 28, 2010. Retrieved March 16, 2012.

- ^ Petroski, Henry (2006). "On the Road". American Scientist. Vol. 94, no. 5. pp. 396–369. doi:10.1511/2006.61.396. ISSN 0003-0996.

- ^ Smith, Jean Edward (2012). Eisenhower in War and Peace. Random House. p. 652. ISBN 978-1400066933.

- ^ Smith (2012), pp. 652–653.

- ^ Smith (2012), pp. 651–654.

- ^ "The Interstate Highway System". History. A&E Television Networks. Archived from the original on May 10, 2019. Retrieved May 10, 2019.

- ^ Norton, Peter (1996). "Fighting Traffic: U.S. Transportation Policy and Urban Congestion, 1955–1970". Essays in History. Corcoran Department of History at the University of Virginia. Archived from the original on February 15, 2008. Retrieved January 17, 2008.

- ^ a b c d Weingroff, Richard F. (Summer 1996). "Three States Claim First Interstate Highway". Public Roads. Vol. 60, no. 1. ISSN 0033-3735. Archived from the original on October 11, 2010. Retrieved February 16, 2008.

- ^ a b Sherrill, Cassandra (September 28, 2019). "Facts and History of North Carolina Interstates". Winston-Salem Journal. Archived from the original on September 29, 2019. Retrieved September 29, 2019.

- ^ Nebraska Department of Roads (n.d.). "I-80 50th Anniversary Page". Nebraska Department of Roads. Archived from the original on December 21, 2013. Retrieved August 23, 2009.

- ^ California Department of Transportation (n.d.). "Timeline of Notable Events of the Interstate Highway System in California". California Department of Transportation. Archived from the original on March 6, 2014. Retrieved March 2, 2014.

- ^ "America Celebrates 30th Anniversary of the Interstate System". US Highways. Fall 1986. Archived from the original on October 24, 2011. Retrieved March 10, 2012.

- ^ "Around the Nation: Transcontinental Road Completed in Utah". The New York Times. August 25, 1986. Archived from the original on March 16, 2017. Retrieved February 9, 2017.

- ^ Utah Transportation Commission (1983). Official Highway Map (Map). Scale not given. Salt Lake City: Utah Department of Transportation. Salt Lake City inset.

- ^ a b Weingroff, Richard F. (January 2006). "The Year of the Interstate". Public Roads. Vol. 69, no. 4. ISSN 0033-3735. Archived from the original on January 4, 2012. Retrieved March 10, 2012.

- ^ Devlin, Sherry (September 8, 1991). "No Stopping Now". The Missoulian. p. E1. Retrieved September 12, 2023 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Free, Cathy (September 15, 1991). "Engineer pleased with his Wallace freeway 'work of art'". The Spokesman-Review. p. B3. Retrieved September 12, 2023 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Idaho Transportation Department (May 31, 2006). "Celebrating 50 years of Idaho's Interstates". Idaho Transportation Department. Archived from the original on February 24, 2012. Retrieved March 10, 2012.

- ^ Colorado Department of Transportation (n.d.). "CDOT Fun Facts". Colorado Department of Transportation. Archived from the original on January 16, 2008. Retrieved February 15, 2008.

- ^ Stufflebeam Row, Karen; LaDow, Eva & Moler, Steve (March 2004). "Glenwood Canyon 12 Years Later". Federal Highway Administration. Archived from the original on January 17, 2013. Retrieved May 11, 2008.

- ^ Neuharth, Al (June 22, 2006). "Traveling Interstates is our Sixth Freedom". USA Today. Archived from the original on August 19, 2012. Retrieved May 9, 2012.

- ^ Johnston, Louis; Williamson, Samuel H. (2023). "What Was the U.S. GDP Then?". MeasuringWorth. Retrieved November 30, 2023. United States Gross Domestic Product deflator figures follow the MeasuringWorth series.

- ^ Minnesota Department of Transportation (2006). "Mn/DOT Celebrates Interstate Highway System's 50th Anniversary". Minnesota Department of Transportation. Archived from the original on December 4, 2007. Retrieved January 17, 2008.

- ^ a b c Sofield, Tom (September 22, 2018). "Decades in the Making, I-95, Turnpike Connector Opens to Motorists". Levittown Now. Archived from the original on April 6, 2020. Retrieved September 22, 2018.

- ^ Pennsylvania Turnpike Commission (n.d.). "Draft: Design Advisory Committee Meeting No. 2" (PDF). I-95/I-276 Interchange Project Meeting Design Management Summary. Pennsylvania Turnpike Commission. Archived from the original (PDF) on October 2, 2013. Retrieved May 11, 2008.

- ^ Federal Highway Administration (n.d.). "Why Does The Interstate System Include Toll Facilities?". Federal Highway Administration. Archived from the original on May 18, 2013. Retrieved July 15, 2009.

- ^ Tuna, Gary (July 27, 1989). "Dawida seeks to merge I-70, turnpike at Breezewood". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. Archived from the original on September 30, 2015. Retrieved November 19, 2015 – via Google News.

- ^ Missouri Department of Transportation (n.d.). "Converting US Route 71 to I-49". Interstate I-49 Expansion Corridor in Southwest District of Missouri. Missouri Department of Transportation. Archived from the original on January 17, 2013.

- ^ New Mexico State Highway and Transportation Department (2007). State of New Mexico Memorial Designations and Dedications of Highways, Structures and Buildings (PDF). Santa Fe: New Mexico State Highway and Transportation Department. p. 14. Archived from the original (PDF) on July 16, 2011.

- ^ a b Walker, Alissa (2022). "About Time: Syracuse's I-81 Is Finally Being Demolished". Curbed.

- ^ McNichol (2006a), pp. 159–160.

- ^ a b Zarroli, Jim (2023). "Why It's So Hard to Tear Down a Crumbling Highway Nearly Everyone Hates". New York Times.

- ^ "Nixon Approves Limit of 55 M.P.H." The New York Times. January 3, 1974. pp. 1, 24. Archived from the original on June 5, 2011. Retrieved July 27, 2008.

- ^ a b Carr, John (October 11, 2007). "State traffic and speed laws". Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Archived from the original on August 7, 2013. Retrieved January 10, 2008.

- ^ Koenig, Paul (May 27, 2014). "Speed Limit on Much of I-295 Rises to 70 MPH". Portland Press Herald. Archived from the original on July 27, 2014. Retrieved July 22, 2014.

- ^ Slater, Rodney E. (Spring 1996). "The National Highway System: A Commitment to America's Future". Public Roads. Vol. 59, no. 4. ISSN 0033-3735. Archived from the original on December 16, 2014. Retrieved January 10, 2008.

- ^ Wolshon, Brian (August 2001). ""One-Way-Out": Contraflow Freeway Operation for Hurricane Evacuation" (PDF). Natural Hazards Review. Vol. 2, no. 3. pp. 105–112. doi:10.1061/(ASCE)1527-6988(2001)2:3(105). Archived from the original (PDF) on October 6, 2008. Retrieved January 10, 2008.

- ^ Faquir, Tahira (March 30, 2006). "Contraflow Implementation Experiences in the Southern Coastal States" (PDF). Florida Department of Transportation. Archived from the original (PDF) on October 25, 2007. Retrieved September 27, 2007.

- ^ McNichol, Dan (December 2006b). "Contra Productive". Roads & Bridges. Archived from the original on July 15, 2011. Retrieved January 10, 2008.

- ^ Mikkelson, Barbara (April 1, 2011). "Interstate Highways as Airstrips". Snopes. Archived from the original on December 1, 2005. Retrieved March 15, 2017.

- ^ Weingroff, Richard F. (May–June 2000). "One Mile in Five: Debunking the Myth". Public Roads. Vol. 63, no. 6. ISSN 0033-3735. Archived from the original on December 12, 2010. Retrieved December 14, 2010.

- ^ Federal Highway Administration (June 30, 2023). "Interstate Highway System: The Myths". Federal Highway Administration. Archived from the original on April 29, 2024. Retrieved June 24, 2024.

- ^ Laskow, Sarah (August 24, 2015). "Eisenhower and History's Worst Cross-Country Road Trip". Slate. Retrieved June 24, 2024.

- ^ a b c d e f American Association of State Highway and Transportation Officials (January 2000). "Establishment of a Marking System of the Routes Comprising the National System of Interstate and Defense Highways" (PDF). American Association of State Highway and Transportation Officials. Archived from the original (PDF) on November 1, 2006. Retrieved January 23, 2008.

- ^ Fausset, Richard (November 13, 2001). "Highway Numerology Muddled by Potholes in Logic". Los Angeles Times. p. B2. Archived from the original on April 2, 2009. Retrieved September 8, 2018.

- ^ McNichol (2006a), p. 172.

- ^ Weingroff, Richard F. (January 18, 2005). "Was I-76 Numbered to Honor Philadelphia for Independence Day, 1776?". Ask the Rambler. Federal Highway Administration. Archived from the original on July 3, 2013. Retrieved January 17, 2008.

- ^ Federal Highway Administration (n.d.). "Interstate FAQ". Federal Highway Administration. Archived from the original on May 7, 2013. Retrieved June 26, 2009.

Proposed I-41 in Wisconsin and partly completed I-74 in North Carolina respectively are possible and current exceptions not adhering to the guideline. It is not known if the US Highways with the same numbers will be retained in the states upon completion of the Interstate routes.

- ^ Essex, Allen (May 2013). "State Adds I-69 to Interstate System". The Brownsville Herald. Archived from the original on February 27, 2017. Retrieved July 17, 2013.

- ^ Federal Highway Administration (March 22, 2007). "FHWA Route Log and Finder List". Federal Highway Administration. Archived from the original on June 5, 2013. Retrieved January 23, 2008.

- ^ a b DeSimone, Tony (March 22, 2007). "FHWA Route Log and Finder List: Additional Designations". Federal Highway Administration. Archived from the original on August 5, 2014. Retrieved January 4, 2010.

- ^ Indiana Department of Transportation (n.d.). "Understanding Interstate Route Numbering, Mile Markers & Exit Numbering". Indiana Department of Transportation. Archived from the original on May 15, 2013. Retrieved November 26, 2011.

- ^ New York State Department of Transportation (n.d.). "Is New York State planning to change its Interstate exit numbering system from a sequential system to a distance-based milepost system?". New York State Department of Transportation. Archived from the original on March 22, 2019. Retrieved January 1, 2003.

- ^ a b American Association of State Highway and Transportation Officials (January 2000). "Establishment and Development of United States Numbered Highways" (PDF). American Association of State Highway and Transportation Officials. Archived from the original (PDF) on November 1, 2006. Retrieved January 23, 2008.

- ^ Federal Highway Administration (n.d.). "Interstate FAQ: Who owns it?". Federal Highway Administration. Archived from the original on May 7, 2013. Retrieved March 4, 2009.

- ^ a b Weingroff, Richard M. (April 7, 2011). "When did the Federal Government begin collecting the gas tax?". Ask the Rambler. Federal Highway Administration. Archived from the original on July 3, 2013. Retrieved June 29, 2011.

- ^ Federal Highway Administration (January 3, 2012). "Funding For Highways and Disposition of Highway-User Revenues, All Units of Government, 2007". Highway Statistics 2007. Federal Highway Administration. Archived from the original on January 17, 2013. Retrieved March 10, 2012.

- ^ Field, David (July 29, 1996). "On 40th birthday, Interstates Face Expensive Midlife Crisis". Insight on the News. pp. 40–42. ISSN 1051-4880.

- ^ VMS, Inc. (n.d.). "Projects by Type: Interstates". VMS, Inc. Archived from the original on September 22, 2007. Retrieved January 10, 2008.

- ^ Hart, Ariel (July 19, 2007). "1st Toll Project Proposed for I-20 East: Plan Would Add Lanes Outside I-285" (PDF). The Atlanta Journal-Constitution. ISSN 1539-7459. Archived from the original (PDF) on October 25, 2007. Retrieved September 27, 2007.

- ^ VanMeter, Darryl D. (October 28, 2005). "Future of HOV in Atlanta" (PDF). American Society of Highway Engineers. Archived from the original (PDF) on October 25, 2007. Retrieved September 27, 2007.

- ^ Weiss, Martin H. (April 7, 2011). "How Many Interstate Programs Were There?". Highway History. Federal Highway Administration. Archived from the original on June 7, 2013. Retrieved March 10, 2012.

- ^ Weingroff, Richard F. (August 2, 2011). "Why Does The Interstate System Include Toll Facilities?". Ask the Rambler. Federal Highway Administration. Archived from the original on May 18, 2013. Retrieved March 10, 2012.

- ^ Federal Highway Administration (November 16, 2011). "Interim Releases for New and Revised Signs". Standard Highway Signs and Markings. Federal Highway Administration. Archived from the original on March 18, 2012. Retrieved March 10, 2012.

- ^ 23 U.S.C. § 103(c), Interstate System.

- ^ Pub. L. 99–599: Surface Transportation Assistance Act of 1978

- ^ American Association of State Highway Officials (September 19, 1967). "Trademark Registration 0835635". Trademark Electronic Search System. United States Patent and Trademark Office. Archived from the original on May 2, 2013. Retrieved April 27, 2014.

- ^ a b Federal Highway Administration (May 10, 2005) [2004]. "Guide Signs" (PDF). Standard Highway Signs (2004 English ed.). Washington, DC: Federal Highway Administration. pp. 3-1 to 3-3. OCLC 69678912. Archived (PDF) from the original on February 5, 2012. Retrieved February 22, 2012.

- ^ Federal Highway Administration (December 2009). "Chapter 2D. Guide Signs: Conventional Roads" (PDF). Manual on Uniform Traffic Control Devices (2009 ed.). Washington, DC: Federal Highway Administration. p. 142. OCLC 496147812. Archived (PDF) from the original on March 15, 2012. Retrieved February 22, 2012.

- ^ Michigan Department of Transportation (2011). Pure Michigan: State Transportation Map (Map). c. 1:221,760. Lansing: Michigan Department of Transportation. Lansing inset. OCLC 42778335, 786008212.

- ^ Texas Transportation Institute (2005). "Ties to Texas" (PDF). Texas Transportation Researcher. Vol. 41, no. 4. pp. 20–21. Archived from the original (PDF) on August 20, 2010.

- ^ American Association of State Highway and Transportation Officials (2006). "Image Gallery". The Interstate is 50. American Association of State Highway and Transportation Officials. Archived from the original on February 25, 2012. Retrieved February 22, 2012.

- ^ American Association of State Highway Officials (1958). Manual for Signing and Pavement Marking of the National System of Interstate and Defense Highways. Washington, DC: American Association of State Highway Officials. OCLC 3332302.

- ^ National Joint Committee on Uniform Traffic Control Devices; American Association of State Highway Officials (1961). "Part 1: Signs" (PDF). Manual on Uniform Traffic Control Devices for Streets and Highways (1961 ed.). Washington, DC: Bureau of Public Roads. pp. 79–80. OCLC 35841771. Archived (PDF) from the original on April 14, 2012. Retrieved February 22, 2012.

- ^ National Joint Committee on Uniform Traffic Control Devices; American Association of State Highway Officials (1971). "Chapter 2D. Guide Signs: Conventional Roads" (PDF). Manual on Uniform Traffic Control Devices for Streets and Highways (1971 ed.). Washington, DC: Federal Highway Administration. p. 88. OCLC 221570. Archived (PDF) from the original on November 29, 2011. Retrieved February 22, 2012.

- ^ National Advisory Committee on Uniform Traffic Control Devices (1978). "Chapter 2D. Guide Signs: Conventional Roads" (PDF). Manual on Uniform Traffic Control Devices for Streets and Highways (1978 ed.). Washington, DC: Federal Highway Administration. p. ((2D-5)). OCLC 23043094. Archived (PDF) from the original on November 29, 2011. Retrieved February 22, 2012.

- ^ Faigin, Daniel P. (December 29, 2015). "Numbering Conventions: Post Miles". California Highways. Archived from the original on January 31, 2017. Retrieved March 15, 2017.[self-published source]

- ^ Zhang, Sarah (October 7, 2014). "An Arizona Highway Has Used the Metric System Since the 80s". Gizmodo. Archived from the original on February 25, 2019. Retrieved February 25, 2019.

- ^ Massachusetts Department of Transportation (n.d.). "Massachusetts Department of Transportation completed projects". Massachusetts Department of Transportation. Retrieved September 20, 2022.

- ^ Hecox, Doug (August 1, 2019). "New FHWA Report Reveals States with the Busiest Highways" (Press release). Federal Highway Administration. Retrieved August 30, 2022.

- ^ a b American Association of State Highway and Transportation Officials (n.d.). "Interstate Highway Fact Sheet" (PDF). American Association of State Highway and Transportation Officials. Archived from the original (PDF) on October 10, 2008. Retrieved February 22, 2012.

- ^ Hall, Jerry & Hall, Loretta (July 1, 2009). "The Adobe Tower: Interesting Items about the Interstate System". Westernite. Western District of the Institute of Transportation Engineers. Archived from the original on September 28, 2013. Retrieved July 23, 2013.

- ^ a b c d Obenberger, Jon & DeSimone, Tony (April 7, 2011). "Interstate System Facts". Route Log and Finder List. Federal Highway Administration. Archived from the original on July 13, 2013. Retrieved February 22, 2012.

- ^ a b Federal Highway Administration (April 6, 2011). "Miscellaneous Interstate System Facts". Federal Highway Administration. Archived from the original on August 5, 2014. Retrieved February 22, 2012.

- ^ "FHWA Route Log and Finder List". Federal Highway Administration. January 31, 2018. Archived from the original on July 11, 2018. Retrieved August 25, 2018.

- ^ Adderly, Kevin (December 31, 2016). "Table 2: Auxiliary Routes of the Dwight D. Eisenhower National System of Interstate and Defense Highways as of December 31, 2016". Route Log and Finder List. Federal Highway Administration. Retrieved September 24, 2017.