International Committee of the Red Cross archives

| Archives of the International Committee of the Red Cross | |

|---|---|

The semi-current archives | |

| |

| 46°13'39.90"N, 6°8'14.10"E | |

| Alternative name | Archives du CICR |

| Location | Switzerland/Geneva, Geneva & Satigny, Switzerland |

| Type | Archive of an International organisation |

| Established | 1863 |

| Affiliation | list of cultural properties in Geneva / Petit-Saconnex[*] |

| Title of director | Head of Archives and Information Management |

| Director | Brigitte Troyon Borgeaud |

| Collection size | 19 kilometers |

| Website | www |

The archives of the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) are based in Geneva and were founded in 1863 at the time of the ICRC's inception.[1] It has the dual function to manage both current records and historical archives.[2] The general historical archives are openly accessible to the general public up to 1975.[1]

Along with the ICRC Library, the archives are widely considered to be the greatest repository for records on International humanitarian law (IHL).[3] They have been dubbed by the Swiss writer Nicolas Bouvier as "the storehouses of sorrow".[4] They preserve the memory of many millions of victims of armed conflicts as "a legacy for mankind".[1]

History

[edit]Early Period

[edit]

The ICRC – or rather its predecessor – was founded in February 1863 at the "Ancient Casino" in the Rue de L'Evêche 3 of Geneva's Old Town by five men: businessman-turned-activist Henry Dunant, who had laid out the basic ideas in his much-acclaimed book A Memory of Solferino; lawyer and philanthropist Gustave Moynier; the medical doctors Louis Appia and Théodor Maunoir; and the General Guillaume Henri Dufour.[5]

At the same moment, its archives came into being:[3]

"Dunant, as secretary, signed off the minutes of the first meeting of the International Committee for Relief to the Wounded, the precursor of the ICRC. Still unaware of what would follow but hopeful that Dunant's vision would bear fruit, the young Committee preserved this document and the ones that followed in order to account for their decisions and actions."[1]

The actual address of the newly founded Red Cross - and thus probably of its fledgling archives – became Dunant's private residence, the third floor of his family's "Maison Diodati" in the Old Town at Rue du Puits-Saint-Pierre 4. It remained there for the first few years.[5] However, as Dunant's colonial businesses in Algeria collapsed, he declared bankruptcy in 1867 and was pushed out of the ICRC by its president Moynier in the following year. It may be assumed that Dunant's ICRC-related records were transferred to Moynier's splendid city residence in Rue de l'Athénée No. 8 at first.[6]

In the first half of the 1870s,[6][5] the ICRC moved into an apartment of a building at Rue de l'Athénée No. 3, just across the street from Moynier's private residence. While it was a very representative address, the office spaces were still rather modest with just three rooms.[7] Likewise, the archives and the library moved into the new Bureau.[5]

During those early years, the archives collected information from various conflicts, especially the 1864 Second Schleswig War between the Kingdom of Prussia and the Austrian Empire on the one hand side, and the Kingdom of Denmark on the other, followed by the Franco-Prussian War (1870–71).[8]

Subsequently, the ICRC archives took over the archival holdings of the Basel Agency with some twelve linear meters of records about prisoners of wars (PoW) from the latter war and of the Trieste Agency with one linear meter of files[2] on PoW from the Great Eastern Crisis in the Balkans between the Russian and Ottoman Empires and their respective allies (1875–1878).[8]

A main focus was the collection of information about the implementation of IHL, particularly with regard to the First Geneva Convention of 1864. However, the primary task of the archives was to record diplomatic correspondence to account for the institution's humanitarian mandate.[1]

In the following decades the archives kept on documenting the evolution of the Red Cross movement.[3] However, those oldest holdings covering more than half a century – the Ancien Fonds – still only amounted to rather modest eight linear meters.[2]

World War I

[edit]

Shortly after the beginning of the First World War in 1914, the ICRC under its president Gustave Ador decided to establish the International Prisoners-of-War Agency (IPWA). Its main task was to trace PoW and to re-establish communications with their respective families. Already at the end of the same year, it had a staff of some 1,200 volunteers who worked in the Musée Rath of Geneva. Many of them were girls, women, and students.[9]

Their mandate was based on resolution VI of the 9th conference of Washington in 1912 and hence limited to military personnel. However, the committee member and medical doctor Frédéric Ferrière founded a civilian section against the advice of other committee members. It soon became commonly associated with the ICRC and significantly contributed to its positive image, thus also to its first Nobel Peace Prize in 1917 (The ousted Dunant had received the first one in 1901 as an individual).[10]

One of its early activists was the French writer Romain Rolland, who volunteered in the sub-division for missing Civilians until July 1915.[11] When he was awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature for 1915, he donated half of the prize money to the Agency.[12] His friend, the Austrian writer Stefan Zweig, provided a lively description of the commitment:

"A rough stool, a small table of unpolished deal, the turmoil of typewriters, the bustle of human beings questioning, calling one to another, hastening to and fro – such was Romain Rolland's battlefield in this campaign against the afflictions of the war. Here, while other authors and intellectuals were doing their utmost to foster mutual hatred, he endeavored to promote reconciliation, to alleviate the torment of a fraction among the countless sufferers by such consolation as the circumstances rendered possible. He neither desired, nor occupied a leading position in the work of the Red Cross; but, like so many other nameless assistants, he devoted himself to the daily task of promoting the interchange of news. His deeds were inconspicuous, and are therefore all the more memorable. [..] Ecce homo! Ecce Poeta!"[9]

Étienne Clouzot (1881–1944) – an archivist palaeographer, who was also a columnist for the liberal daily newspaper Journal de Genève (which had published an anonymous essay by Dunant about Solferino and thus played a role in the founding of the ICRC, illustrating the networking connections of Geneva's patrician family dynasties) – became the director of one of the Entente sections and designed the classification system for the millions of index cards.[6]

Between the World Wars

[edit]

At the end of 1918, the ICRC – along with its archives and library – moved to its new headquarters at the Promenade du Pin at the edge of the Old Town.[6] In the following year, Clouzot (see above) rose to be head of the ICRC Secretariat in 1919, and therefore took over the responsibility for the running of the archives and the library.[6]

"In the 1920s, after a brief period in which many different methods of records management were used, the Secretariat arranged its archives in two main groups, one for legal, diplomatic and administrative matters, the other for operations, under the auspices of the Committee's Delegation Commission (Commission des Missions)."[2]

The IPWA stopped operating in 1924, but the ICRC archives kept on collecting information from various armed conflicts which in many cases may be considered a continuation of WWI. Amongst them were:

- the Greco-Turkish War (1919–1922),

and after a relatively quite decade[2]

- the Chaco War (1932–1935),

- the Second Italo-Ethiopian War (1935–1936),

- the Spanish Civil War (1936–1939),

- and the Second Sino-Japanese War (starting in 1937).[1]

Only in 1930 did the ICRC start to keep and store personal files on its staff, a practise which illustrated

"the new tasks in the realm of coordinating humanitarian action that began to fall to the ICRC."[8]

In 1932/33, the ICRC moved its headquarters away from the Old Town to the "Villa Moynier". It had been built in 1848 for the Banker Barthélemy Paccard and was then owned by his son-in-law Gustave Moynier (1826–1910), who was the first president of the ICRC and stayed in that office for a record-term of 47 years until his death. Situated in the middle of the large Parc Moynier on the shores of Lake Geneva, the Villa had housed the League of Nations in 1926.[6] It was also during those two decades between the two world wars that the ICRC developed

"notions of historical memory and preserving memory for the sake of all humanity in relation to the archives".[1]

World War II

[edit]

The IWPA was re-opened two weeks after the beginning of the Second World War as the Central Agency for Prisoners of War, now based on the mandate from the 1929 Geneva Convention. Once again, Étienne Clouzot played a prominent role:

"in 1939, fuelled by his experience in the International Prisoners of War Agency, he helped organize the Central Prisoners of War Agency, becoming a member of its Technical Directorate"[6]

Another key person became Suzanne Ferrière, who had assisted her uncle Frédéric at the IPWA during WWI and now instituted a new family messaging system.[13]

Already in October 1939, IBM "provided the Agency free of charge with both staff and Watson machines. The latter, thanks to a perforated card system, made it possible to sort and classify information at high speed."[14] Faced with a gigantic growth of personal and institutional data which was handled by some 3,000 staff, the ICRC in 1942 introduced its first filing system. Altogether, the number of index cards rose to about 45 million and the number of transmitted messages to some 120 million, reflecting the new dimensions of human suffering.[1] The ICRC's efforts were awarded in 1944 with its second Nobel Peace Prize after 1917.

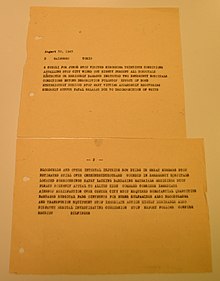

One of the last – and most important – documents from the WWII period was issued on 29 August 1945, only days before the end of the war, by Fritz Bilfinger, an ICRC delegate who reached the apocalyptic ruins of Hiroshima just some three weeks after the United States Army Air Forces (USAAF) dropped the atomic bomb "Little Boy" on the Japanese city. His telegram, kept in the archives, recorded a chilling warning of the horrors of the Atomic Age:

"conditions appalling stop city wiped out, eighty percent all hospitals destroyed or seriously damaged; inspected two emergency hospitals, conditions beyond description full stop effect of bomb mysteriously serious stop many victims, apparently recovering, suddenly suffer fatal relapse due to decomposition of White blood cells and other internal injuries, now dying in great numbers stop estimated still over one hundred thousand wounded in emergency hospitals located surroundings, sadly lacking bandaging materials, medicines stop."[15]

Decolonisation and "Cold War"

[edit]

In 1946/47 the ICRC moved its headquarters from the Villa Moynier to the former Carlton Hotel, built in 1876. The neoclassical building on a hill above the Palace of Nations was provided to the organisation by the Canton of Geneva through a long-term lease.[16] At the same time, the IHL expert Jean Pictet (1914–2002) - who hailed from a Geneva family owning Pictet & Cie bank and played a key role in drafting the 1949 Geneva Conventions for the protection of victims of war – created the Archives Division:

"A general comprehensive filing plan was then adopted in 1950 – the so-called 'Pictet Plan', in reference to its creator, Jean Pictet, who was then director of the Division of General Affairs, which included the archives. The filing plan comprised both thematic and geographic referential numbering. It applied to the whole institution until 1972 and to the Archives Division until 1997."[1]

Meanwhile, the ICRC archives grew with the increase of conflicts during decolonisation and the so-called Cold War, which was a "hot war" in many places. They included:

- the French Indochina War (1946–1954);

- the 1948 Palestinian expulsion and flight;

- the Korean War (1950–1953);

- the Suez Crisis and the Hungarian Revolution (1956);

- the Algerian War of Independence (1954–1962);

- the Congo Crisis (1960–1965);

- the Cuban Missile Crisis (1962)

- the North Yemen Civil War (1962–1970);

In 1963, the ICRC received its third Nobel Peace Prize after 1917 and 1944, making it the recipient of the most awards up to now. Already three years ago, the Central PoW Agency had acquired a permanent status within the ICRC as the Central Tracing Agency.[1] Thus it was prepared to expand its activities in more conflicts that broke out in subsequent years, particularly in:

- the Vietnam War (1964–1975);

- the Six-Day War of 1967;

- the Nigeria-Biafra War (1967–1970);

- the Greek junta (1967–1974);

- the coup d'état against President Salvador Allende in Chile (1973);

- the 1973 Yom Kippur War;

- the 1974 Cyprus conflict;

- the end of the Portuguese colonial empire in the wars of independence in Mozambique and Angola (1975); and

- the Cambodian genocide (1975–1979) and Cambodian–Vietnamese War (1978–1989)[1][17][18]

Until 1973, public access to records of the archives was generally barred, though the ICRC directorate could consider individual requests. It was 110 years after its inception that the ICRC Assembly as the governing body of the organisation formalised this case-by-case practise as a first step of opening up:

"The system of ad hoc derogations allowing access to select archival materials was however denounced by researchers as being incoherent, partial and subjective. Furthermore, by the late 1970s and 1980s, the social mood began channelling growing criticism towards the ICRC's perceived role and stance during the Second World War, specifically regarding the Nazi genocide and concentration camps. Voices were raised across society calling for accountability for the perceived lack of action by the ICRC, and for transparency in relation to its past. The institution's reputation was being challenged from several angles. If prior to this the ICRC had managed its image by mostly keeping its archives out of the public arena, it seemed that maintaining its reputation depended on bringing them to the fore, albeit with due respect for confidentiality. In terms of public image, transparency was becoming a stronger tool than secrecy."[1]

In 1979, the ICRC created a precedent when it granted unlimited access to Jean-Claude Favez, professor at the University of Geneva, for his study about the role of the ICRC in the Holocaust.[1] He only published his book in 1988, but it was groundbreaking both for Switzerland in general and the ICRC in particular. Just in the previous year, the former top-diplomat Cornelio Sommaruga had become the new ICRC President. He has been widely credited for leading the opening of the archives, which in 1984 had moved into a newly constructed seven-storey administrative office block next to the historical "Le Carlton" headquarters, symbolising the transition into a modern archival culture.[16]

Yet, despite Sommaruga's efforts the ICRC governing body took its time. Hence, it was only at the very end of the Cold War – in May 1990 – that the ICRC Assembly finally confirmed the mandate of the Archives Division to comply with the "principles of modern archiving" and open up.[1] However, researchers still had to sign an agreement not to publish their findings without the assent of the ICRC. Texts had to be submitted and were subject to having material deleted.[19]

Post-Cold War

[edit]It took almost another six years – until January 1996 – that the ICRC Assembly officially adopted the right of the general public for access to the archives[17] and defined a policy of transparency.[18] Protective embargo periods were ruled to be fifty years for general archives and 100 years for personal files.[8] "It is worth noting that some within the ICRC had proposed even longer protection periods." Subsequently, the files of the general archives from 1863 to 1950 were opened to the public in full,[1] altogether almost 500 linear metres of records.[8]

The first researcher to enjoy the opening was the British human rights journalist Caroline Moorehead, who was writing an official chronicle of the ICRC history: Dunant's Dream.[20] She was soon followed by the French historian and nazi hunter Serge Klarsfeld with his association of the" Sons and Daughters of Jews Deported from France". Already two years later he published a collection of documents from the archives about the internment and deportation of French Jews during WWII.[21]

In 1997, the archives adopted a new filing plan – B AI (Services généraux – Archives institutionnelles) – which included computerized documents.[1]

In 2004, the archives released a second set of general archives containing the files from 1951 to 1965, again some 500 linear metres.[8] In the same year, the ICRC Assembly reduced the protection period for general files from fifty to forty years, and the embargo on personal files from one hundred to sixty years.[1]

On 19 June 2007, the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organisation (UNESCO) added the IWPA archives to the Memory of the World Register

"to prevent collective amnesia, promote the conservation of archive and library collections throughout the world and ensure that they are disseminated as widely as possible."[22]

In 2008/9, a rotunda was constructed at the HQ administrative building which houses the archives, providing a new reception area for visiting researchers as well.[16]

In 2010, the Public Archives were merged with the ICRC Library and the ICRC Photos archives under the umbrella of the ICRC Information Management service to cope with the growing complexity of big data and at the same time the fragmentation of information due to the rapid evolution of digital technologies.[23] In the same year, the ICRC formally adopted an electronic filing system, called B RF (Services généraux – Archives générales des unités, Reference Files).[1] Subsequently, tailormade automation processes, including more recently the use of artificial intelligence (ai), have been explored to adequately preserve the institutional memory.[23]

As part of this modernisation process, the archives expanded in 2011 into the new ICRC logistics hub in Satigny, near Geneva Airport. Construction was partly financed by the Swiss government, and the land was provided by the canton of Geneva. The main archives and library services to the public have stayed at the HQ though.[24]

In 2015, the archives released its third batch from the general files on the armed conflicts up to 1975 (see above), including information on Nelson Mandela's detention.[17]

In 2017, the ICRC once again revised the access rules to its public archives: protection periods were increased by ten years in order to ensure confidentiality as the ICRC standard operating principle and data privacy protection, especially with regard to protracted conflicts. This means that the embargo on general files is back to fifty years as between 1996 and 2004, while individual files stay closed for seventy years.[25] According to these new rules of access,

"the next section of the ICRC general archives, covering the period from 1976 to 1985, will be opened to the public in 2035."[1]

Collections and Holdings

[edit]The public and audiovisual archives are divided into five sections:

- The general public archives contain documents, mostly in French language, which cover the history of the ICRC since its foundation in 1863 until 1975;

- The Tracing Agency archives, which feature data about Individuals, are technically open to the public until the 1950s. However, they are not open to general consultation as people have to go through the ICRC's tracing archivists. The only exception are all individual records relating to some two million prisoners of WWI- especially records of capture, of transfers between camps and of deaths in detention – which were made accessible online. The index cards primarily deal with the Western, Romanian and Serbian Fronts.[26] Consultation of files on PoW and civilian internees during the Spanish Civil War or the Second World War requires specific skills. Hence, anyone can request information on an individual but the archives accept only a limited amount of requests per year because of limited resources. The tracing archives' files about people caught up in more recent conflicts are closed to the public, but the person visited in detention or their family can obtain information upon request.

- The photo library and archives contain more than 800,000 images from the ICRC's global activities since the 1860s. About 125,000 of them have been made available to the public in digital format.

- The film archives contain, as of early 2020, around 5,000 titles with some 1,000 hours of footage covering the ICRC's humanitarian work in conflicts around the world from 1921 to the present day, in a range of formats (video, 35 mm and 16 mm film).[27]

- The audio archives hold more than 10,000 digitized sound files with thousand of hours of content, starting in the second half of the 1940s.[28]

The archives also hold private collections of documents that were deposited by former members of the Committee and delegates.[2]

As of early 2020, the ICRC archives held approximately:

- 9 million digital documents,

- 19 linear kilometers of shelf space for paper records,

- 34 terrabytes of audiovisual electronic media, and

- 41 million Index cards about individual persons from the two World Wars.

About 1.500 researchers on average consult the archives and library collections – both public and closed ones – every year.

For 2019, the archives counted around 1.4 million page views on its websites. In the course of the same year, its staff handled about 11,000 requests, both external and internal ones.[23]

Galleries

[edit]The IPWA during WWI

[edit]The Central Agency during WWII

[edit]The public archives at the Headquarters (since 1984)

[edit]The non-public archives in Satigny (since 2011)

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s McKnight Hashemi, Valerie (2018). "A balancing act: The revised rules of access to the ICRC Archives reflect multiple stakes and challenges" (PDF). International Review of the Red Cross. 100(1-2-3) (907–909): 373–394. doi:10.1017/S1816383119000316. S2CID 197734726.

- ^ a b c d e f Guide to the archives of intergovernmental organizations. Paris: United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO). 1999. pp. 127–134.

- ^ a b c "Library". International Committee of the Red Cross. Retrieved 8 June 2020.

- ^ Helg, Didier (October 1995). "Focus on Humanity A Century of Photography The ICRC Archives – Nicolas Bouvier, Michèle Mercier and François Bugnion, Focus on humanity. A century of photography. Archives of the International Committee of the Red Cross, Skira, Geneva, 1995". International Review of the Red Cross. 35 (308): 579–580. doi:10.1017/S0020860400089695.

- ^ a b c d Durand, Roger; Rouèche, Michel (1986). Ces lieux où Henry Dunant (in French and English). Geneva: Société Henry Dunant. pp. 36–43, 54–55. ISBN 9782881630033.

- ^ a b c d e f g Raboud, Ismaël; Niederhauser, Matthieu; Mohr, Charlotte (2018). "Reflections on the development of the Movement and international humanitarian law through the lens of the ICRC Library's Heritage Collection". International Review of the Red Cross. 100, Nr. (1-2-3) (907–909): 143–163. doi:10.1017/S1816383119000365. S2CID 200043656.

- ^ Chenevière, Jacques (June 1967). "The First "Prisoners of War Agency" Geneva 1914–1918". International Review of the Red Cross. 75.

- ^ a b c d e f Pitteloud, Jean-François (31 October 1996). "New access rules open the archives of the International Committee of the Red Cross to historical research and to the general public". International Review of the Red Cross. 314.

- ^ a b Zweig, Stefan (1921). Romain Rolland; the man and his work. New York: T. Seltzer. pp. 268–270.

- ^ Ferrière, Adolphe (1948). Le Dr Frédéric Ferrière. Son action à la Croix-Rouge internationale en faveur des civils victimes de la guerre (PDF) (in French). Geneva: Editions Suzerenne, Sarl. pp. 27–41. Archived from the original (PDF) on 28 April 2016. Retrieved 7 June 2020.

- ^ Billeter, Nicole (2005). Worte machen gegen die Schändung des Geistes!. Kriegsansichten von Literaten in der Schweizer Emigration 1914/1918 (in German). Bern: Peter Lang Verlag. ISBN 3-03910-417-9.

- ^ Schazmann, Paul-Emile (February 1955). "Romain Rolland et la Croix-Rouge" (PDF). Revue internationale de la Croix-Rouge et Bulletin international des Sociétés de la Croix-Rouge. 37. Comité international de la Croix-Rouge. doi:10.1017/S1026881200125735. S2CID 144703916.

- ^ "Death of Miss S. Ferriere, Honorary Member of the ICRC" (PDF). International Review of the Red Cross. 10 (109): 210–211. April 1970. doi:10.1017/S0020860400064226.

- ^ "The ICRC and the private sector" (PDF). International Committee of the Red Cross. 6 December 2016. p. 20. Retrieved 20 July 2020.

- ^ Bernard, Vincent; Policinski, Ellen (30 March 2017). "Nuclear weapons: Rising in defence of humanity". Humanitarian Law & Policy. Retrieved 29 July 2020.

- ^ a b c Kuntz, Joëlle (2017). International Geneva : 100 years of architecture. Geneva: Éditions Slatkine. pp. 132–139. ISBN 978-2-8321-0842-0.

- ^ a b c "ICRC archives to be opened, 1966–1975". INTERNATIONAL COMMITTEE OF THE RED CROSS. 10 June 2015. Retrieved 6 June 2020.

- ^ a b Pitteloud, Jean-François (2004). "The International Committee of the Red Cross reduces the protective embargo on access to its archives" (PDF). International Review of the Red Cross. 86 (856): 958–962. doi:10.1017/S1560775500180538. S2CID 145301901.

- ^ Baer, George (1993). International Organizations, 1918–1945: A Guide to Research and Research Materials. Wilmington: Scholarly Resources. pp. 33–34. ISBN 978-0842023092.

- ^ Moorehead, Caroline (21 September 2012). "Literary non-fiction: the facts". The Guardian. Retrieved 12 September 2020.

- ^ "New book on ICRC's role during Second World War". International Committee of the Red Cross. 12 December 1999. Retrieved 27 July 2020.

- ^ The International Prisoners-of-War Agency: The ICRC in World War One (PDF). Geneva: International Committee of the Red Cross / Musée international de la Croix-Rouge et du Croissant-Rouge. 2007.

- ^ a b c Troyon Borgeaud, Brigitte (24 May 2021). "Le CICR: un service qui s'adapte à l'environnement informationnel". Arbido – die Fachzeitschrift für Archiv, Bibliothek und Dokumentation (in French). 2020 / 1.

- ^ "Inauguration of ICRC's new logistics hub". Genève internationale. 14 September 2011. Retrieved 7 June 2020.

- ^ Troyon Borgeaud, Brigitte (3 May 2017). "Rules governing Access to the Archives of the International Committee of the Red Cross – Adopted by the Assembly of the International Committee of the Red Cross on 2 March 2017" (PDF). International Committee of the Red Cross. Retrieved 8 June 2020.

- ^ "The Archives of the International Prisoners-of-War Agency 1914–1919" (PDF). INTERNATIONAL COMMITTEE OF THE RED CROSS. 24 July 2014. Retrieved 6 June 2020.

- ^ "The ICRC's audiovisual collections". International Committee of the Red Cross. Retrieved 17 June 2020.

- ^ "Contacting the ICRC archives". INTERNATIONAL COMMITTEE OF THE RED CROSS. 3 January 2017. Retrieved 6 June 2020.