Internal iliac artery

| Internal iliac | |

|---|---|

Front of abdomen, showing surface markings for arteries and inguinal canal. | |

| |

| Details | |

| Source | Common iliac artery |

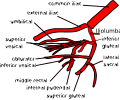

| Branches | Iliolumbar artery, lateral sacral artery, superior gluteal artery, inferior gluteal artery, middle rectal artery, uterine artery, obturator artery, inferior vesical artery, superior vesical artery, obliterated umbilical artery, internal pudendal artery, vaginal artery |

| Vein | Internal iliac vein |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | arteria iliaca interna |

| MeSH | D007083 |

| TA98 | A12.2.15.001 |

| TA2 | 4302 |

| FMA | 18808 |

| Anatomical terminology | |

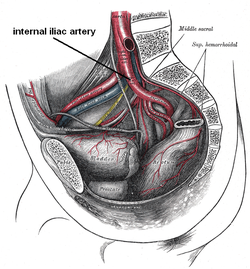

The internal iliac artery (formerly known as the hypogastric artery) is the main artery of the pelvis.

Structure

[edit]The internal iliac artery supplies the walls and viscera of the pelvis, the buttock, the reproductive organs, and the medial compartment of the thigh. The vesicular branches of the internal iliac arteries supply the bladder.[1]

It is a short, thick vessel, smaller than the external iliac artery, and about 3 to 4 cm in length.

Course

[edit]The internal iliac artery arises at the bifurcation of the common iliac artery, opposite the lumbosacral articulation, and, passing downward to the upper margin of the greater sciatic foramen, divides into two large trunks, an anterior and a posterior.

It is posterior to the ureter,[2] anterior to the internal iliac vein,[2] anterior to the lumbosacral trunk, and anterior to the piriformis muscle. Near its origin, it is medial to the external iliac vein, which lies between it and the psoas major muscle. It is above the obturator nerve.

Branches

[edit]The arrangement of branches of the internal iliac artery is extremely variable.[3] Typically, the artery divides into an anterior division and a posterior division, with the posterior division giving rise to the superior gluteal, iliolumbar, and lateral sacral arteries. The rest usually arise from the anterior division. Because it is variable, an artery may not be a direct branch, but instead might arise off a direct branch.

In recent years the development of techniques like prostate artery embolisation and angiografy led to an increased understanding of the prostate vascularisation. Regarding the arterial supply M. de Assis et al. has suggested an anatomic classification for the origin of the inferior vesical artery [4]

The following are the branches of internal iliac artery:

Anastamoses

[edit]In individuals who are biological females, the ovarian artery (a branch of the abdominal aorta) and uterine arteries form anastomoses.[6]

Fetal structure

[edit]In the fetus, the internal iliac artery is twice as large as the external iliac, and is the direct continuation of the common iliac. It ascends along the side of the bladder, and runs upward on the back of the anterior wall of the abdomen to the umbilicus, converging toward its fellow of the opposite side.

Having passed through the umbilical opening, the two arteries, now termed umbilical, enter the umbilical cord, where they coil around the umbilical vein, and ultimately ramify in the placenta.

At birth, when the placental circulation ceases, the pelvic portion only of the umbilical artery remains patent gives rise to the superior vesical artery (or arteries) of the adult; the remainder of the vessel is converted into a solid fibrous cord, the medial umbilical ligament (otherwise known as the obliterated hypogastric artery) which extends from the pelvis to the umbilicus.

Variation

[edit]In two-thirds of a large number of cases, the length of the internal iliac varied between 2.25 and 3.4 cm.; in the remaining third it was more frequently longer than shorter, the maximum length being about 7 cm. the minimum about 1 cm.[citation needed]

The lengths of the common iliac and internal iliac arteries bear an inverse proportion to each other, the internal iliac artery being long when the common iliac is short, and vice versa.

The place of division of the internal iliac artery varies between the upper margin of the sacrum and the upper border of the greater sciatic foramen.

The right and left hypogastric arteries in a series of cases often differed in length, but neither seemed constantly to exceed the other.[citation needed]

Common branching variations

[edit]-

The typical example[7]

Collateral circulation

[edit]The circulation after ligature of the internal iliac artery is carried on by the anastomoses of:[8]

- the iliolumbar artery (from the posterior division of the internal iliac artery) with the last lumbar artery (from the aorta)

- the iliolumbar artery (from the posterior division of the internal iliac artery) with the superficial circumflex iliac artery (from the femoral)

- the lateral sacral arteries (from the posterior division of the internal iliac artery) with the median sacral artery (from the aorta)

- the superior gluteal artery (from the posterior division of the internal iliac artery) with the superficial circumflex iliac artery (from the femoral)

- the inferior gluteal artery (from the anterior division of the internal iliac artery) with the profunda femoris artery (from the femoral)

- the obturator artery (from the anterior division of the internal iliac artery) with the inferior epigastric artery (from the external iliac artery)

- the obturator artery (from the anterior division of the internal iliac artery) with the medial circumflex femoral artery (from the profunda femoris artery)

- the middle rectal artery (from the anterior division of the internal iliac artery) and the superior rectal artery (a branch of the inferior mesenteric artery)

- the uterine arteries (from the anterior division of the internal iliac artery) and the ovarian arteries (from the aorta)

Additional images

[edit]-

Volume rendered CT scan of abdominal and pelvic blood vessels.

-

Bifurcation of the aorta and the right iliac arteries - side view.

-

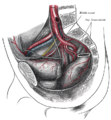

Dissection of side wall of pelvis showing sacral and pudendal plexuses.

-

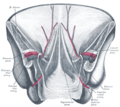

Sacral plexus of the right side.

-

Posterior view of the anterior abdominal wall in its lower half. The peritoneum is in place, and the various cords are shining through.

-

Posterior abdominal wall, after removal of the peritoneum, showing kidneys, suprarenal capsules, and great vessels.

-

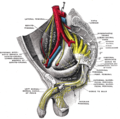

The arteries of the internal organs of generation of the female, seen from behind.

-

Male hypogastric artery

-

Female hypogastric artery

-

Lumbar and sacral plexus. Deep dissection. Anterior view.

-

Lumbar and sacral plexus. Deep dissection. Anterior view.

-

Lumbar and sacral plexus. Deep dissection. Anterior view.

-

Pelvic contents: male. Superior view. Deep dissection.

-

Hypogastric vessels

-

Internal iliac arteries

-

Lumbar and sacral plexus. Deep dissection. Anterior view.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]![]() This article incorporates text in the public domain from page 614 of the 20th edition of Gray's Anatomy (1918)

This article incorporates text in the public domain from page 614 of the 20th edition of Gray's Anatomy (1918)

- ^ Kaplan Qbook - USMLE Step 1 - 5th edition - page 52

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x Paterson-Brown, Sara (2010-01-01), Bennett, Phillip; Williamson, Catherine (eds.), "Chapter Five - Applied anatomy", Basic Science in Obstetrics and Gynaecology (Fourth Edition), Churchill Livingstone, pp. 57–95, ISBN 978-0-443-10281-3, retrieved 2021-01-13

- ^ Tunstall R (2016-05-06). "Internal iliac arteries". In Tubbs RS, Shoja MM, Loukas M (eds.). Bergman's Comprehensive Encyclopedia of Human Anatomic Variation. Wiley. p. 1456. doi:10.1002/9781118430309. ISBN 978-1-118-43035-4.

- ^ de Assis, André Moreira; Moreira, Airton Mota; de Paula Rodrigues, Vanessa Cristina; Harward, Sardis Honoria; Antunes, Alberto Azoubel; Srougi, Miguel; Carnevale, Francisco Cesar (August 2015). "Pelvic Arterial Anatomy Relevant to Prostatic Artery Embolisation and Proposal for Angiographic Classification". CardioVascular and Interventional Radiology. 38 (4): 855–861. doi:10.1007/s00270-015-1114-3. ISSN 0174-1551. PMID 25962991. S2CID 9680972.

- ^ Drake, Richard L.; Wayne Vogl; Adam W. M. Mitchell (2020). Gray's anatomy for students (4th ed.). Philadelphia. p. 490. ISBN 978-0-323-39304-1. OCLC 1085137919.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Uterine artery and ovarian artery anatomy, retrieved 2022-11-30

- ^ Essential Clinical Anatomy. K.L. Moore & A.M. Agur. Lippincott, 2 ed. 2002. Page 224

- ^ Arisudhan Anantharachagan, Sarris, I. and Ugwumadu, A. (2011). Revision Notes for the MRCOG Part 1. Oxford Oxford University Press -07-01. pages 90-91

External links

[edit]- Anatomy photo:44:10-0100 at the SUNY Downstate Medical Center

- Radiology image: Pelvis:15PelArt from Radiology Atlas at SUNY Downstate Medical Center (need to enable Java)

- Cross section image: pelvis/pelvis-e12-2—Plastination Laboratory at the Medical University of Vienna

- Illustration at wiseowl.com

- "Variation in Origin of the Parietal Branches of internal iliac artery based on a study of 169 Specimens (108 males and 61 females)." at anatomyatlases.org

- MedicalMnemonics.com: 1169 801 3160

- pelvis at The Anatomy Lesson by Wesley Norman (Georgetown University) (pelvicarteries)

![The typical example[7]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/e/e1/Variation_1_of_internal_iliac_artery_branching.svg/120px-Variation_1_of_internal_iliac_artery_branching.svg.png)