Igor Sechin

Igor Sechin | |

|---|---|

Игорь Сечин | |

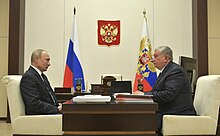

Sechin in 2020 | |

| Chief Executive Officer of Rosneft | |

| Assumed role 23 May 2012 | |

| Preceded by | Eduard Khudainatov |

| Deputy Prime Minister of Russia | |

| In office 12 May 2008 – 21 May 2012 | |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Igor Ivanovich Sechin 7 September 1960 Leningrad, Russian SFSR, Soviet Union (now Saint Petersburg, Russia) |

| Spouse(s) | Marina Sechina (div. 2011) Olga Rozhkova

(m. 2012; div. 2017) |

| Children | 3 |

| Residence(s) | Moscow, Russia |

| Salary | ~$17,500,000 (2014)[1] |

Igor Ivanovich Sechin (Russian: И́горь Ива́нович Се́чин; born 7 September 1960) is a Russian oligarch and a government official, considered a close ally and "de facto deputy" of Vladimir Putin.[2]

Sechin has been a confidant of Russian leader Vladimir Putin since the early 1990s. Sechin was chief of staff to Putin when he was the deputy mayor of St. Petersburg in 1994. When Putin became President in 2000, Sechin became his deputy chief of staff, overseeing security services and energy issues in Russia.[3][4] Putin appointed Sechin as chairman of Rosneft, the Russian state oil company in 2004.[5][4] He was as Deputy Prime Minister of Russia in Vladimir Putin's cabinet from 2008 to 2012.[6] He is currently the chief executive officer, president and chairman of the management board of Rosneft.[5]

Sechin is often described as one of Putin's most conservative counselors and the leader of the Kremlin's Siloviki faction, a lobby gathering former security services agents.[7][8][9][a] He has been sanctioned by some foreign governments following the Russian invasion of Ukraine. His nickname is Darth Vader.[10][11]

Career

[edit]

Sechin graduated from Leningrad State University in 1984 as a linguist, fluent in Portuguese and French.[12] In the 1980s, Sechin worked in Mozambique. He was officially a Soviet interpreter.[13] From 1991 to 1996, he worked at Saint Petersburg mayor's office, and became a chief of staff of the first deputy mayor, Vladimir Putin in 1994.[14] From 1996 to 1997, Sechin served as a deputy of Vladimir Putin, who worked in the presidential property management department. From 1997 to 1998, Sechin was the chief of the general department of the main control directorate attached to the president, led by Putin. In August 1999, he was appointed head of the secretariat of the prime minister of Russia, Putin. From 24 November 1999 until 11 January 2000, Sechin was the first deputy chief of the Russian presidential administration.

Between 31 December 1999 and May 2008, he was deputy chief of Putin's administration.[b][c] In May 2008, he was appointed by President Dmitry Medvedev as a deputy prime minister in a move considered as a demotion.[22] According to Stratfor, "Sechin acts as boss of Russia's gigantic state oil company Rosneft and commands the loyalty of the FSB. Thus, he represents the FSB's hand in Russia's energy sector."[23]

On 27 July 2004, Sechin became the successful and influential chairman of the board of directors of JSC Rosneft, which swallowed up the assets of jailed tycoon Mikhail Khodorkovsky's Yukos. He has additionally been president of Rosneft since May 2012. Khodorkovsky has accused Sechin of plotting to have him arrested and plundering his oil company: "The second as well as the first case were organised by Sechin. He orchestrated the first case against me out of greed and the second out of cowardice."[24] In 2008, Sechin allegedly blocked the replacement of the AAR consortium[clarification needed] with Gazprom in the TNK-BP joint venture.[25][d]

In 2008, Sechin was involved with the BP oil company and did private negotiations with the BP's CEO Bob Dudley.[26] In 2008, Hugo Chávez said that the idea for Venezuelan nuclear energy program came from Sechin. Sechin negotiated deals on weapons and nuclear technology deliveries to Venezuela.[27][28] In July 2009, Sechin negotiated deals with Cuba that brought Russia into deep-water drilling in the Gulf of Mexico.[29]

Sechin also presides over the board of directors of the United Shipbuilding Corporation, and helped with negotiations with France over the purchase of four Mistral-class ships. Sechin argued that two ships should be constructed in Russia and two in France, as opposed to the initial offer that only one be constructed in Russia.[30] Piotr Żochowski, of the Polish Center for Eastern Studies, argued that "it cannot be ruled out that Sechin's stance on this issue results from his personal financial involvement in the St Petersburg shipbuilding industry".[30]

On 12 April 2011, Sechin resigned from the board of Rosneft upon President Medvedev's 31 March 2011 order for senior officials to resign from large companies.[31] After Vladimir Putin became President of Russia in May 2012, he later resigned as vice prime minister on 21 May 2012 and rejoined the executive board of Rosneft as chairman and became the executive secretary for the Russia Federation's commission on the development strategy of the fuel and energy complex and environmental safety (Russian: комиссии по вопросам стратегии развития ТЭКа и экологической безопасности) in June.[32][33][e]

In December 2014, a CNBC article noted that Sechin is "widely believed to be Russia's second-most powerful person" after President Putin.[37] In December 2017, The Guardian noted that Sechin "is widely seen as the second most powerful man in Russia after Vladimir Putin".[38]

The Steele dossier alleged that Sechin met with Carter Page in 2016 as a representative of the Donald Trump presidential campaign, and offered Trump the brokerage of a 19.6% private share in Rosneft in exchange for lifting sanctions imposed following the 2014 Russian intervention in Ukraine.[39][40][41][f] The 2019 Mueller Report did not corroborate those allegations, and neither Page nor Sechin were indicted with any crime.[43]

Sechin was instrumental in the arrest and trial of Putin's former minister of economy, Alexei Ulyukaev, charged and found guilty of soliciting a bribe from Sechin. The verdict was delivered after hearing testimony from Sechin in a closed trial, and is another indicator, according to the Financial Times, of the power wielded by Sechin in Russian politics.[44]

In November 2018, Sechin released a statement at the first Russian-Chinese Energy Business Forum in Beijing, about increased levels of cooperation between Rosneft and Chinese owned energy companies, citing "increased protectionism and threats of trade wars" as a reason for the cooperation.[45][46] Agreements of cooperation were signed between Rosneft and Chinese Hengli Group and include expansion in exploration as well as production and refining.[47]

Sanctions

[edit]On 20 March 2014, the United States government sanctioned Sechin in response to the Russian government's role in the ongoing unrest in Ukraine. The sanctions include a travel ban to the United States, freezing of all assets of Sechin in the United States and a ban on business transactions between American citizens and corporations and Sechin and businesses he owns.[48][49] Closely associated with Sechin, Rosneft is on the Sectoral Sanctions Identification (SSI) List.[50]

On 28 February 2022, in relation to the Russian invasion of Ukraine, the European Union blacklisted Sechin and had all his assets frozen.[51] In March, the UK government imposed sanctions which involved freezing Sechin's assets and a travel ban.[52][53] Two superyachts belonging to Sechin, the Amore Vero and the Crescent, had been seized by Spanish and Italian authorities by mid-March as a consequence.[54]

Sechin was sanctioned by the UK government in 2022 in relation to Russo-Ukrainian War.[55]

Personal life

[edit]Sechin has been married twice. He divorced his first wife Marina Sechina (Russian: Марина Сечина) in 2011.[56] Marina increased her wealth after the divorce and made The Paradise Papers and, as of 2017, owns a mansion at Serebryany Bor (Russian: Серебряный Бор) in the Khoroshyovo-Mnyovniki District of the North-Western Administrative Okrug of Moscow.[57][58][59][60][61] After 5 years of marriage, he divorced his second wife Olga Rozhkova (Russian: Ольга Рожкова; born 1990) on 14 June 2017.[61][62][63] Olga sailed on the 85.6-metre (281 ft) St Princess Olga which was built by Oceanco in 2012 and delivered in 2013.[64][65][66][67] After the divorce, the super-yacht was renamed Amore Vero ("True Love") in 2017.[63]

With Marina, he has a daughter, Inga (b. 1982), who graduated from the Saint Petersburg Mining University and, as of 2018, works at Surgutneftegasbank (Russian: Сургутнефтегазбанк).[68] Inga married Dmitry Ustinov (b. 1979), a Russian intelligence agent and graduate of the FSB Academy,[69] and son of former Prosecutor General and current Plenipotentiary Envoy to the Southern Federal District Vladimir Ustinov,[g] in 2003. Inga and Dmitry had a son on 4 July 2005.[70][71] She divorced him and, later, she married Timerbulat Karimov (Russian: Тимербулат Каримов) (b. 1974), a former investment banker and senior vice-president of VTB Bank from October 2011 until February 2014. He is on the board of directors for the Russian Copper Company (Russian: АО «Русская медная компания») which is the third largest in Russia and owned by Igor Altushkin. Since September 2015, she is the only owner of the Moscow based company Khoroshiye Lyudi or Good People (Russian: ООО «Хорошие люди»), which on 4 December 2015, became a 40% owner of the Novgorod Agropark (Russian: ООО «Новгородский агропарк»),[h] a turkey farm located in Veliky Novgorod.[72][73][74][75]

After the demotion of Vladimir Ustinov in 2006, Sechin reportedly arranged the appointment of Alexander Bastrykin, another ally of his, as Chairman of the Investigative Committee of the Prosecutor General's Office in 2007 in order to retain his influence.[76][77][78]

His son Ivan (b. 1989), from his marriage to Marina, graduated from the Lomonosov business school at Moscow State University and worked closely with Igor at Rosneft, as of 2018, as First Deputy Director of the Department of Joint Offshore Projects.[79] Ivan was sanctioned by the U.S. in February 2022.[80] Ivan died on 5 February 2024 under "bizarre circumstances". He was at his home mansion in the Moscow region and woke in the middle of the night complaining to his wife of kidney pain. His security service immediately called an ambulance, but they made a mistake and didn't provide the correct address of the mansion. As a result the ambulance took two hours to arrive, by which time Ivan died. The official diagnosis was blood clot. His father sought an investigation into the security detail.[81]

Varvara is his daughter from his marriage to Olga.[61][79]

Notes

[edit]- ^ Other siloviki close to Sechin include Nikolai Patrushev, Alexander Bortnikov, and Viktor Ivanov.[9]

- ^ Oleg Vladimirovich Feoktistov (Russian: Олег Владимирович Феоктистов; born 3 July 1964, Moscow Oblast),[15] also known as "Oleg the Big" or "General Fix" or "General Ficus", served as a border guard in Karelia with Ivan Ivanovich Tkachev (Russian: Иван Иванович Ткачёв; born 1970), who later would head the "K" Directorate of the SEB of the FSB beginning in 2016 after the resignation of Viktor Voronin (Russian: Виктор Воронин),[16] and fought with the Soviet Army during the Soviet–Afghan War where he met the KGB military counterintelligence officer Sergei Shishin (Russian: Сергей Шишин), who later became the head of the special forces of the FSB CSS, and then the head of the FSB Economic Support Service.[17] Shishin guided Feoktistov but became embroilled in scandals during 2007 after which Shishin transferred to the Office of seconded employees, then seconded to VTB Bank, and three years later he joined the management of RusHydro and the Igor Sechin associated Rosneft.[17] Feoktistov graduated from the FSB Academy and, in 2004, headed the newly formed FSB's Internal Security Directorate also known as the 6th Service or CSS (Russian: «Шестерка») of the FSB, which is responsible for the operational support of criminal cases and The New Times called "Sechin's Special Forces" because it was created on an initiative of Igor Sechin while Igor Sechin was the deputy head of the presidential administration.[15][17][18][19] In September 2016, Feoktistov officially became the head of the security service of Rosneft.[15]

- ^ As of 2024, Boris Antonovich Boyarskov (Russian: Борис Антонович Боярсков; born 9 July 1953, Leningrad) is allegedly a retired KGB general, is very close to Igor Sechin of Rosneft but was often at odds with Mikhail Lesin and Mikhail Seslavinsky while Seslavinsky was at Rospechat (Russian: Роспечать).[20][21] From 1994 until 1999, Boyarskov headed the security at the Sergey Rodionov associated bank Imperial after which he was considered for head of security of the Central Bank of Russia but instead worked for the bank JSCB Evrofinance for three years until it merged with CB Mosnarbank to form JSCB Evrofinance Mosnarbank in December 2003.[20][21] In 2004, he graduated from the Higher School of Economics (Russian: ГУ ВШЭ) with an MBA in Finance.[20] With support from St Petersburg Security Forces, Boyarskov later headed Rossvyazokhrankultura from 22 March 2007 until 2 June 2008.[20]

- ^ Alfa Group–Access Industries–Renova consortium (AAR) was led by Mikhail Fridman, Len Blavatnik, and Viktor Vekselberg through their companies, TNK, Sidanko, and Onako and their subsidiaries.[25]

- ^ Revealed in a 16 August 2012 article in Forbes, several of Sechin's Rosneft employees gained access to Vyacheslav Volodin associated Prisma terminals (Russian: Терминалы «Призма»), which are also called Volodin's Prisma (Russian: Призма Володина), following the 4 December 2011 Russian legislative elections and the Snow revolution, during which Volodin actively used his Prisma terminal, which he received on the eve of the elections, to counter dissidents in Russia. According to its developers at the Medialogia company (Russian: «Медиалогия»), Prisma tracks in real time 60 million sources and shows the dynamics of negative and positive comments from blogs on a particular event, can build graphs of bot attacks and individually track topics. The website for the Medialogia Company states that Prisma "monitors activities in social media that lead to an increase in social tension: escalation of riots, protest sentiments, extremism; discussion of the level of prices, wages, pensions; problems of housing and communal services, infrastructure, medicine and others." (Russian: "отслеживает в соцмедиа активности, приводящие к росту социальной напряжённости: нагнетание беспорядков, протестные настроения, экстремизм; обсуждение уровня цен, зарплат, пенсий; проблемы ЖКХ, инфраструктуры, медицины и другие")[34][35][36]

- ^ Also, Page met with Igor Diveykin (Russian: Игорь Дивейкин), who was a deputy chief for internal policy with interests about United States elections during the meeting and, since 22 March 2021, has headed the the State Duma Apparatus replacing Tatyana Gennadievna Voronova (Russian: Татьяна Геннадьевна Воронова).[40][42]

- ^ In 2010, Vladimir Ustinov's daughter and Dmitry Ustinov's sister, Irina Dmitrievna Ustinova (Russian: Устинова Ирина Дмитриевна) lived in Sochi and is an assistant prosecutor in south Russia's Khostinsky district (Russian: Хостинский район), a district of the city of Sochi.[69]

- ^ The other owners are 40% by Ildus Fahretdinov (Russian: Ильдус Фахретдинов) through an Ufa "Investment Company" LLC (Russian: ООО «Инвестиционная компания») and 20% by Oleg Chernyavsky through the Moscow "Negotsiant TK" LLC (Russian: ООО «Негоциант ТК»).[72] In 2015, Russia produced nearly 150 thousand tons of turkey by slaughter weight. The Novgorod Agropark expects to produce from 22 to 30 thousand tons per year.

References

[edit]- ^ "25 самых дорогих руководителей компаний: ежегодный рейтинг Forbes (The 25 Most Expensive Company Executives: Annual Rating)". Forbes.ru (in Russian). 18 November 2015. Retrieved 3 March 2022.

- ^ The Guardian. 12 January 2017. Page 6.

- ^ Foy, Henry (1 March 2018). "'We need to talk about Igor': the rise of Russia's most powerful oligarch". Financial Times. Retrieved 3 March 2022.

- ^ a b Reznik, Irina; Bierman, Stephen; Meyer, Henry (7 February 2014). "State-run Russian oil behemoth Rosneft helps Vladimir Putin tighten his economic grip". Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286. Retrieved 3 March 2022.

- ^ a b Hussain, Yadullah (10 March 2020). "Meet the Russian oil tycoon who likely triggered the Riyadh-Moscow oil war". Financial Post, a division of Postmedia Network Inc. Archived from the original on 20 March 2020. Retrieved 10 March 2020.

- ^ Luhn, Alec (8 February 2017). "The "Darth Vader" of Russia: meet Igor Sechin, Putin's right-hand man". Vox. Retrieved 3 March 2022.

- ^ Hahn, Gordon (21 July 2008). "The Siloviki Downgraded. In Russia's New Configuration of Power". Archived from the original on 31 December 2010. Retrieved 11 December 2016.

- ^ "Igor Sechin, head of Rosneft, is powerful as never before". The Economist. 15 December 2016. ISSN 0013-0613. Retrieved 27 July 2019.

- ^ a b Harding, Luke (21 December 2007). "Putin, the Kremlin power struggle and the $40bn fortune". The Guardian. Retrieved 11 February 2020.

- ^ Bidder, Benjamin (19 October 2012). "Putins Petroleum-Coup". Der Spiegel (in German). Archived from the original on 19 October 2012. Retrieved 22 October 2020.

- ^ Rapoza, Kenneth (27 May 2019). "Russia's Largest Public Companies 2019: Sanctions No Match For Oil & Gas". Forbes. Archived from the original on 12 April 2020. Retrieved 22 October 2020.

- ^ "Игорь Сечин: Путин везде берет его с собою" [Igor Sechin: Putin takes him everywhere with him]. news.ru (in Russian). 18 May 2005. Archived from the original on 8 June 2008. Retrieved 18 December 2018.

- ^ Сечин, Игорь. [Sechin, Igor] (in Russian). Lenta.ru.

- ^ "Igor Sechin: Rosneft's Kremlin hard man comes out of the shadows". the Guardian. 18 October 2012. Retrieved 3 March 2022.

- ^ a b c "Генерал ФСБ, который затеял дело против Алексея Улюкаева. Кто он? Краткая биография руководителя службы безопасности «Роснефти»" [The FSB general who started the case against Alexei Ulyukaev. Who is he? Brief biography of the head of the security service of Rosneft]. «Медуза» (meduza.io) (in Russian). 15 November 2016. Archived from the original on 24 September 2024. Retrieved 1 October 2024.

- ^ Стогней, Анастасия (Stogney, Anastasia); Малкова, Ирина (Malkova, Irina) (31 July 2019). "«Коммерческие ребята»: как ФСБ крышует российские банки" ["Commercial Guys": How the FSB Protects Russian Banks]. The Bell (thebell.io) (in Russian). Archived from the original on 24 September 2024. Retrieved 1 October 2024.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c Канев, Сергей (Kanev, Sergey) (22 August 2016). "За что убрали генерала Фикса: В центральном аппарате ФСБ продолжаются масштабные зачистки: лишился своего кабинета 1-й заместитель начальника Управления собственной безопасности (УСБ) ФСБ генерал Олег Феоктистов, известный как «Олег-Большой» или «генерал Фикс»" [Why General Fiks was removed: Large-scale cleansing continues in the central apparatus of the FSB: the 1st Deputy Head of the Internal Security Directorate (CSS) of the FSB, General Oleg Feoktistov, known as "Oleg the Big" or "General Fiks", lost his office]. «Новые Времена» (NewTimes.ru). Archived from the original on 24 September 2024. Retrieved 1 October 2024.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Романова, Анна (Romanova, Anna); Корбал, Борис (Korbal, Boris) (4 December 2017). "Конец спецназа Сечина: «Дело Улюкаева» стало последней разработкой еще вчера могущественного генерала ФСБ Олега Феоктистова. Члены его команды покидают Лубянку, а иные отправляются в СИЗО и даже в бега" [The End of Sechin's Special Forces: The "Ulyukaev case" was the latest development of the powerful FSB General Oleg Feoktistov yesterday. Members of his team leave the Lubyanka, and some go to jail and even go on the run]. «Новые Времена» (NewTimes.ru). Archived from the original on 24 September 2024. Retrieved 1 October 2024.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Канев, Сергей (Kanev, Sergey) (27 June 2016). "Большая чистка: В главном институте путинского режима началась большая чистка: из центрального аппарата ФСБ отправили в отставку несколько генералов, которые до этого считались неприкасаемыми, а на некоторых чекистов рангом пониже заведены уголовные дела. Источники на Лубянке утверждают: самое «вкусное» управление ФСБ — Службу экономической безопасности — берет под контроль «сечинский спецназ». The New Times изучал внутривидовую борьбу чекистских кланов" [Big Cleaning: A major purge has begun in the main institution of the Putin regime: several generals who had previously been considered untouchables were dismissed from the central apparatus of the FSB, and criminal cases were opened against some Chekists of a lower rank. Sources in the Lubyanka claim that the most "tasty" department of the FSB - the Economic Security Service - is taking control of the "Sechin special forces". The New Times studied the intraspecific struggle of the Chekist clans]. «Новые Времена» (NewTimes.ru) (in Russian). Archived from the original on 8 November 2018. Retrieved 1 October 2024.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c d "ДОСЬЕ: БОЯРСКОВ БОРИС АНТОНОВИЧ" [DOSSIER: BOYARSKOV BORIS ANTONOVICH]. kgb-net (in Russian). 6 October 2023. Archived from the original on 6 October 2023. Retrieved 2 October 2024.

- ^ a b "За лицензии будут бороться ВГТРК и банк "Еврофинанс"" [VGTRK and Eurofinance Bank to compete for licenses]. «Грани.ру» (grani.ru) (in Russian). 11 June 2004. Archived from the original on 23 November 2004. Retrieved 2 October 2024.

- ^ A Lineup Aimed at Taming Siloviki Archived 31 July 2008 at the Wayback Machine. The Sunday Times. 15 May 2008.

- ^ "Russia: The FSB Branches Out". stratfor. Retrieved 3 March 2022.

- ^ "Jailed tycoon Mikhail Khodorkovsky 'framed' by key Putin aide". The Sunday Times. 18 May 2008. Archived from the original on 27 July 2008. Retrieved 3 March 2022.

- ^ a b Yenikeyeff, Shamil (November 2011). "BP, Russian billionaires, and the Kremlin: a Power Triangle that never was" (PDF). Oxford Energy Comment. Retrieved 24 November 2011.

- ^ TNK-BP Is Hurting Russia. Archived 7 December 2009 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Russia Offers Venezuela's Chavez Weapons, Nuclear Cooperation[dead link]. Bloomberg. 25 September 2008.

- ^ Kramer, Andrew E. (16 October 2010). "Russia Plans Nuclear Plant in Venezuela". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 3 March 2022.

- ^ "Russia to drill for oil off Cuba". 29 July 2009. Retrieved 3 March 2022.

- ^ a b Piotr Żochowski (11 October 2010). "Russia's interest in the Mistral: the political and military aspects". OSW Centre for Eastern Studies. Retrieved 3 March 2022.

- ^ Сечин вышел из совета директоров "Роснефти" [Sechin resigned from Rosneft's board of directors]. BBC (in Russian). 12 April 2011. Retrieved 20 March 2020.

- ^ И.Сечин вошел в список ста наиболее влиятельных людей мира: Глава "Роснефти" Игорь Сечин стал единственным россиянином, включенным в ежегодно составляемый журналом Time список из ста наиболее влиятельных в мире людей. [I. Sechin entered the list of the hundred most influential people in the world: The head of Rosneft, Igor Sechin, was the only Russian included in the list of the hundred most influential people in the world annually compiled by Time magazine.]. RBK (in Russian). 18 April 2013. Archived from the original on 27 March 2016. Retrieved 20 March 2020.

- ^ Топалов, Алексей (Topalov, Alexey); Орлова, Юлия (Orlova, Yulia) (22 May 2012). Директор-распорядитель: Игорь Сечин, вице-премьер в правительстве Владимира Путина, теперь возглавит госкомпанию «Роснефть» [Managing Director: Igor Sechin, Deputy Prime Minister in the government of Vladimir Putin, will now head the state-owned company Rosneft]. Gazeta.Ru (in Russian). Retrieved 20 March 2020.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Бурибаев, Айдар (Buribaev, Aidar); Баданин, Роман (Badanin, Roman) (15 August 2012). "Как власти читают ваши блоги: расследование Forbes" [How authorities read your blogs: Forbes investigation]. Forbes (in Russian). Archived from the original on 20 August 2021. Retrieved 1 October 2024.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Forbes рассказал о системе анализа блогов для чиновников" [Forbes spoke about a blog analysis system for officials]. «Лента.ру» (in Russian). 16 August 2012. Archived from the original on 26 October 2023. Retrieved 1 October 2024.

- ^ "Платформа ПРИЗМА" [PRISMA Platform]. «Медиалогия» (mlg.ru) (in Russian). September 2024. Archived from the original on 1 September 2024. Retrieved 1 October 2024.

- ^ Peleschuk, Dan (24 December 2014). "Think it's just Putin who runs Russia? Guess again". CNBC. Archived from the original on 25 December 2014. Retrieved 25 December 2014.

- ^ "Ex-minister's harsh jail sentence sends shockwaves through Russian elite". The Guardian. 15 December 2017. Retrieved 15 December 2017.

- ^ Bertrand, Natasha (27 January 2017). "Memos: CEO of Russia's state oil company offered Trump adviser, allies a cut of huge deal if sanctions were lifted". Business Insider. Retrieved 21 March 2020.

- ^ a b Isikoff, Michael (23 September 2016). "U.S. intel officials probe ties between Trump adviser and Kremlin". Yahoo News. Retrieved 21 March 2020.

- ^ Post staff (21 March 2016). "A transcript of Donald Trump's meeting with The Washington Post editorial board". Washington Post. Retrieved 21 March 2020.

- ^ "В Государственной Думе сменится руководитель Аппарата: Татьяна Воронова покинет свой пост. Его займет Игорь Дивейкин, который на данный момент является Первым заместителем руководителя Аппарата ГД" [The head of the State Duma will be replaced: Tatyana Voronova will leave her post. It will be occupied by Igor Diveykin, who is currently the First Deputy Chief of Staff of the State Duma]. State Duma (duma.gov.ru) (in Russian). 22 March 2021. Archived from the original on 24 March 2021. Retrieved 1 October 2024.

- ^ Scarborough, Rowan (18 April 2019). "Carter Page exonerated by Mueller report". Associated Press. Archived from the original on 4 May 2019. Retrieved 4 May 2019.

- ^ "'We need to talk about Igor': the rise of Russia's most powerful oligarch". Financial Times (subscription required). 28 February 2018. Retrieved 15 January 2019.

- ^ "Protectionism, trade wars motivate Russia and China to step up cooperation — Rosneft head". TASS (in Russian). Retrieved 15 January 2019.

- ^ Ellyatt, Holly (29 November 2018). "Business leaders hail Russia's booming energy ties with China". CNBC. Retrieved 15 January 2019.

- ^ "Rosneft and Chinese Hengli Group signed a cooperation agreement, that includes E&P projects". www.worldoil.com. Archived from the original on 16 January 2019. Retrieved 15 January 2019.

- ^ "Announcement Of Additional Treasury Sanctions On Russian Government Officials And Entities". US Department of the treasury.

- ^ "Executive Order - Blocking Property of Additional Persons Contributing to the Situation in Ukraine". The White House - Office of the Press Secretary. 20 March 2014.

- ^ Rapoza, Kenneth (23 June 2017). "Here's How Europe's Russian Sanctions Differ From Washington's". Forbes. Retrieved 29 April 2020.

- ^ Valentina Pop; Sam Fleming; Max Seddon (28 February 2022). "EU freezes assets of Russia's leading oligarchs and allies of Putin". The Financial Times.

- ^ "UK freezes assets of seven Russian oligarchs including Roman Abramovich". The Guardian. 10 March 2022. Retrieved 10 March 2022.

- ^ "Abramovich and Deripaska among 7 oligarchs targeted in estimated £15 billion sanction hit". GOV.UK. Retrieved 13 September 2023.

- ^ "Mega yacht 'owned by oligarch and Putin ally Igor Sechin' seized by Spanish authorities". The Independent. 10 March 2022. Retrieved 16 March 2022.

- ^ "CONSOLIDATED LIST OF FINANCIAL SANCTIONS TARGETS IN THE UK" (PDF). Retrieved 16 April 2023.

- ^ Пузырев, Денис (Puzyrev, Denis) (22 September 2017). Роднички энергии: как связаны РАО ЕЭС, Марина Сечина и санаторий в Кашире: Связанный со структурами бывшей жены Игоря Сечина санаторий «Каширские роднички» стал причиной конфликта не из-за статуса лечебно-оздоровительного центра. В дальнем Подмосковье столкнулись интересы крупных энерготрейдеров [Energy springs: how RAO UES, Marina Sechina and the sanatorium in Kashira are related: The Kashirskiye Rodnichki sanatorium, connected with the structures of Igor Sechin's ex-wife, did not cause the conflict because of the status of the health center. The interests of large energy traders clashed in the far suburbs of Moscow]. RBK (in Russian). Retrieved 20 March 2020.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Paradise Papers". OCCRP. Retrieved 20 March 2020.

- ^ Shleynov, Roman (5 November 2017). "Wife of Putin's Number Two Man Gets Rich Quick". OCCRP. Retrieved 20 March 2020.

- ^ Шлейнов, Роман (Shleynov, Roman) (8 November 2017). Как бывшая супруга главы «Роснефти», не имевшая ни рубля дохода, сразу после развода обзавелась активами на миллиарды рублей и компанией на Каймановых островах [As the former wife of the head of Rosneft, who did not have a single ruble of income, immediately after the divorce, she acquired billions of rubles of assets and a company in the Cayman Islands]. Novaya Gazeta (in Russian). Retrieved 20 March 2020.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Васильев, Иван (Vasiliev, Ivan) (6 November 2017). Марина Сечина назвала бредом информацию из «Райского досье»: По ее словам, она никогда не инвестировала в проекты австрийского бизнесмена Джулиуса Майнла [Marina Sechina called delirium information from the "Paradise dossier": According to her, she never invested in the projects of the Austrian businessman Julius Meinl]. Vedomosti (in Russian). Retrieved 20 March 2020.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c "Олигарх Игорь Сечин развелся с молодой супругой" [Oligarch Igor Sechin divorced his young wife]. 24СМИ [online] «24smi.org» (in Russian). 14 November 2017. Retrieved 10 November 2020.

- ^ Игорь Сечин развелся во второй раз: Глава «Роснефти» Игорь Сечин развелся с супругой Ольгой, свидетельствуют данные базы мировых судов. Заявление о расторжении брака пара подала еще в апреле [Igor Sechin divorced for the second time: The head of Rosneft, Igor Sechin, divorced his wife Olga, according to the data base of the magistrates' courts. The couple filed for divorce in April]. RBK. 15 November 2017. Retrieved 20 March 2020.

- ^ a b Демьянова, Саша (Demyanova, Sasha) (17 November 2017). Игорь Сечин после развода переименовал роскошную яхту, носившую имя бывшей жены [Igor Sechin after the divorce renamed the luxury yacht that bore the name of his ex-wife]. Cosmopolitan (in Russian). Retrieved 20 March 2020.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Anin, Roman (2 August 2016). "The Secret of the St. Princess Olga". OCCRP. Retrieved 20 March 2020.

- ^ Anin, Roman (1 August 2016). "Секрет "Принцессы Ольги". Текст статьи с опровержением по решению Басманного суда" [The Secret of Princess Olga. The text of the article with a refutation by the decision of the Basmanny court]. Novaya Gazeta (in Russian). No. 83. Retrieved 20 March 2020.

- ^ SYT Staff (30 October 2012). "85 Metre Oceanco on seatrials today". Superyacht Times. Retrieved 20 March 2020.

- ^ Janssen, Maarten (10 February 2013). "85.6 Metre Oceanco St. Princess Olga delivered". Superyacht Times. Retrieved 20 March 2020.

- ^ "Marina Sechina: biography and photos". ruarrijoseph.com. 2018. Retrieved 10 November 2020.

- ^ a b "Высокопоставленные наследники: Чем занимаются жены и дети российского премьера, его заместителей и полпредов президента?" [High Ranking Heirs: What do the wives and children of the Russian prime minister, his deputies and presidential plenipotentiaries do?]. ladno.ru (in Russian). 26 October 2010. Archived from the original on 15 April 2018. Retrieved 18 December 2018.

- ^ "Дочь Игоря Сечина родила от сына Владимира Устинова" [Igor Sechin's daughter gave birth to his son Vladimir Ustinov] (in Russian). newsru.com. 8 July 2005. Archived from the original on 1 July 2018. Retrieved 22 March 2018.

- ^ "Igor Sechin has grandson" (in Russian). Moskovskij Komsomolets. 8 July 2005. Archived from the original on 19 March 2007. Retrieved 22 March 2018.

- ^ a b "Семейный бизнес лучше банковского: Тимербулат Каримов покинул ВТБ" [Family business is better than banking: Timerbulat Karimov left VTB]. Kommersant. 6 February 2014. Retrieved 22 March 2018.

- ^ Osipov, Anton (3 October 2011). "Тимербулат Каримов стал старшим вице-президентом ВТБ" [Timerbulat Karimov became Senior Vice President of VTB] (in Russian). Vedomosti. Retrieved 26 March 2018.

- ^ "Тимербулат Каримов: Член совета директоров АО "Русская медная компания"" [Timerbulat Karimov: Member of the Board of Directors of JSC Russian Copper Company] (in Russian). Atlanty. Retrieved 22 March 2018.

- ^ Burlakova, Ekaterina (25 May 2016). "заинтересовалась производством индейки: Компания, совладельцем которой является Инга Каримова, дочь главы "Роснефти" Игоря Сечина, собирается инвестировать в производство индейки в Новгородской области объемом около 30 тыс. т в год" [Sechin's daughter company interested in turkey production: The company, co-owned by Inga Karimova, the daughter of the head of Rosneft Igor Sechin, is going to invest in the production of turkey in the Novgorod region of about 30 thousand tons per year] (in Russian). RBC. Retrieved 22 March 2018.

- ^ Бастрыкин, Александр [Bastrykin, Alexander] (in Russian). Lenta.ru.

- ^ Однокашник президента возглавит прокурорское следствие [Presidential classmate will lead the prosecution investigation] (in Russian). Kommersant.ru. 22 June 2007.

- ^ Stanovaya, Tatyana (22 June 2007). "Сечинский комитет при Генпрокуратуре | Политком.РУ [Sechin committee at the Prosecutor General's Office]". Политком.RU: информационный сайт политических комментариев. Retrieved 3 March 2022.

- ^ a b Мельникова, Алина (Melnikova, Alina) (9 November 2018). "Игорь Сечин: биография, личная жизнь, семья, жена, дети — фото" [Igor Sechin: biography, personal life, family, wife, children - photo]. Krestyanka (in Russian). Retrieved 10 November 2020.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Here are the Russian oligarchs targeted in Biden's sanctions". NBC News. 26 February 2022. Retrieved 12 March 2022.

- ^ Quinn, Allison (20 February 2024). "Putin Ally's Son Drops Dead at 35 in Bizarre Circumstances". The Daily Beast – via Yahoo! News.

External links

[edit]- 1960 births

- Living people

- Businesspeople from Saint Petersburg

- 20th-century Russian politicians

- 21st-century Russian businesspeople

- Russian businesspeople in the oil industry

- GRU officers

- Arms traders

- Rosneft

- Russian individuals subject to U.S. Department of the Treasury sanctions

- Russian individuals subject to United Kingdom sanctions

- Russian individuals subject to European Union sanctions

- 21st-century Russian politicians

- Politicians from Saint Petersburg

- Russian oligarchs

- Specially Designated Nationals and Blocked Persons List

- Aides to the President of Russia