Iceman (1984 film)

| Iceman | |

|---|---|

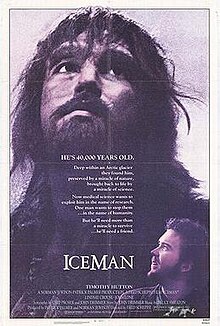

Original film poster | |

| Directed by | Fred Schepisi |

| Written by |

|

| Produced by |

|

| Starring | |

| Cinematography | Ian Baker |

| Edited by | Billy Weber |

| Music by | Bruce Smeaton |

| Distributed by | Universal Pictures |

Release date |

|

Running time | 100 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $10 million[1] |

| Box office | $7.3 million[2][3] |

Iceman is a 1984 American sci-fi drama film from Universal Pictures directed by Fred Schepisi, written by John Drimmer and Chip Proser, and starring Timothy Hutton, Lindsay Crouse, and John Lone. The film follows the discovery of a prehistoric Neanderthal caveman frozen in ice and what happens after scientists are able to bring him back to life. It was filmed in color with Dolby sound and has a running time of 100 minutes. The DVD version was released in 2004.

The film was met with positive reviews.

Plot

[edit]Anthropologist Stanley Shephard is brought to an arctic base when explorers discover the body of a prehistoric Neanderthal caveman who has been frozen for 40,000 years. After thawing the body to perform an autopsy, scientists first attempt – and succeed – to resuscitate the "iceman".

The dazed Neanderthal is alarmed by the surgical-masked figures; only Shephard has the presence of mind to remove his mask and reveal his humanity and somewhat familiar (bearded) face, permitting the iceman to settle into a peaceful recuperating sleep.

The scientists place the iceman in an artificial, simulated environment for study, though the caveman quickly deduces that he is far from home. Shephard believes that the caveman's culture may provide clues to learning about the human body's adaptability, citing ceremonies such as firewalking. Other scientists see the potential in studying the caveman's DNA and his survival in the ice, for possible "freezing" of the sick until treatment is possible.

Shephard defends the caveman's right to be considered a human being and not a scientific specimen. Despite opposition from the others, Shephard initiates an encounter with the caveman. Shephard names him "Charlie" after the iceman introduces himself as "Char-u". Shephard and Charlie bond, but it becomes obvious to the anthropologist that Charlie misses his world.

A linguist is brought to the Arctic base, and the scientists make progress communicating with Charlie. Shephard introduces Charlie to colleague Dr. Diane Brady. Assuming that the woman is Shephard's mate, Charlie makes lines in the sand which indicate that he likely was a married man with children before he was frozen.

Shephard strives to understand what motivates Charlie and why he survived being frozen. At one point, Shephard begins to sing "Heart of Gold", inspiring Charlie to sing one of his own songs. Charlie's line drawings in the ground resemble a bird, matching body markings on his chest. When the base's helicopter strays over the roof of Charlie's area, he takes on an obsessive zeal as he climbs towards the roof. Shouting the word Beedha, he lifts his arms towards the helicopter in a sign of worship. Even though the helicopter pulls away from the dome, Shephard knows that Charlie can now think of nothing else.

Shephard consults local Inuit who recognize the name that Charlie chanted and explain that it is a mythical bird, a messenger for the gods. Shephard understands that Charlie has a spiritual side and that he was on a dreamwalk pilgrimage, a mythical quest for redemption. His people were dying in the sudden ice age; he must have offered himself to the gods in the form of a self-sacrifice or appealing to the gods to redeem his tribe.

Charlie escapes after watching Shephard exit the biosphere. In a panic of seeing unfamiliar modern devices, and believing they are his enemies, he accidentally spears Maynard, one of the base's technicians, before being recaptured and Shephard's experiment is put to an end. However, Shephard helps Charlie to escape into the wild. Charlie races on ahead of Shephard as they pass by glaciers and ice-shelves, and a crevasse opens up in front of Shephard, cutting him off from Charlie.

When the helicopter emerges over an ice-shelf, Shephard looks on helplessly as Charlie grabs hold of one of its landing skis. In an attempt to evade Charlie's grasp, the helicopter pilot pulls up, but Charlie dangles beneath the aircraft while it continues to climb high into the sky. Charlie is ecstatic, believing the "messenger" is taking him to his god. He releases his grip, seeming to float through the sky while he plunges to his death.

Shephard's initial horror turns into joy, as he realizes that Charlie has reached his "dreamwalk" goal that he began 40,000 years earlier, even though it means his death.

Cast

[edit]- Timothy Hutton as Dr. Stanley Shephard

- Lindsay Crouse as Dr. Diane Brady

- John Lone as Charlie

- Josef Sommer as Whitman

- David Strathairn as Dr. Singe

- Philip Akin as Dr. Vermeil

- Danny Glover as Loomis

- Amelia Hall as Mabel

- Richard Monette as Hogan

- James Tolkan as Maynard

Production

[edit]This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (October 2016) |

Iceman was a project linked to director Norman Jewison for several years in the 1970s. Jewison still produced the film, which was eventually made under Australian director Fred Schepisi.[4]

Exteriors were filmed in British Columbia and Manitoba.[5][6] Schepisi worked with Australian collaborators Ian Baker for cinematography and Bruce Smeaton for music.[5]

Reception

[edit]Box office

[edit]The film was released on April 13, 1984 grossing $1,836,120 (US). By the end of its four-week release, it grossed $7,343,032 (US).[3]

Critical reception

[edit]Critic Richard Scheib said, "The film was part of a brief revival of the old caveman vs dinosaurs genre, along with Quest for Fire and Clan of the Cave Bear, in which earlier action-fantasy films were redressed with a much stricter regard to anthropological realism. Iceman, using modern science, became one of the more refreshingly intelligent films. The film is knowingly well-informed on anthropology and biochemistry and never resorts to cheap cliche or hackneyed elements."[7] Harlan Ellison called the film "magnificent", citing excellent acting (particularly on the part of John Lone) and directing that contribute to genuine emotional appeal.[8]

Roger Ebert of the Chicago Sun-Times, called it "spellbinding storytelling". "It begins with such a simple premise and creates such a genuinely intriguing situation that we're not just entertained, we're drawn into the argument [between using Charlie as a scientific specimen or a man]".[4]

Colin Greenland reviewed Iceman for Imagine magazine, and stated that "Caught in the middle is John Lone as the Neanderthal, a sensitive, wry performance. Beautiful photography too."[9]

Home media

[edit]The film was released in 4:3 pan and scan on DVD by Universal on December 28, 2004. Kino Lorber released the film on Blu-ray on December 10, 2019, preserving the original 2.35:1 aspect ratio.

References

[edit]- ^ "Iceman (1984)". AFI. Retrieved April 9, 2024.

- ^ Iceman at Box Office Mojo

- ^ a b "Movie Iceman - Box Office Data". the-numbers.com. Retrieved 2007-10-06.

- ^ a b Ebert, Roger (1984-01-01). "Iceman". Chicago Sun-Times. Retrieved 2017-12-27 – via RogerEbert.com.

- ^ a b "Iceman Review". cinephilia.net.au. Retrieved 2007-10-06.

- ^ "Iceman". amctv.com. Archived from the original on 2007-10-05. Retrieved 2007-10-06.

- ^ Scheib, Richard. "Iceman". Moria: Science Fiction, Horror & Fantasy Review. Archived from the original on 2007-10-19. Retrieved 2007-10-09.

- ^ Ellison, Harlan (2015-03-10). Harlan Ellison's Watching: Essays and Criticism. Open Road Media. pp. 175–177. ISBN 9781497604117.

- ^ Greenland, Colin (April 1985). "Fantasy Media". Imagine (review) (25). TSR Hobbies (UK), Ltd.: 47.

External links

[edit]- Iceman at IMDb

- Iceman at the TCM Movie Database

- Iceman at Letterboxd

- Iceman at Rotten Tomatoes

- 1984 films

- 1980s English-language films

- 1984 science fiction films

- Films set in the Arctic

- Films about suspended animation

- Fiction about Neanderthals

- Films directed by Fred Schepisi

- Films scored by Bruce Smeaton

- Universal Pictures films

- Films about cavemen

- American science fiction drama films

- 1980s American films

- Films produced by Norman Jewison

- English-language science fiction films