W. Ian Lipkin

This article's lead section may be too short to adequately summarize the key points. (February 2021) |

W. Ian Lipkin | |

|---|---|

Lipkin in 2008 | |

| Born | 18 November 1952 |

| Education | University of Chicago Laboratory School |

| Alma mater | |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields |

|

| Institutions | |

| Website | www.mailman.columbia.edu |

Walter Ian Lipkin (born November 18, 1952) is the John Snow Professor of Epidemiology at the Mailman School of Public Health at Columbia University and a professor of Neurology and Pathology at the College of Physicians and Surgeons at Columbia University. He is also director of the Center for Infection and Immunity, an academic laboratory for microbe hunting in acute and chronic diseases. Lipkin is internationally recognized for his work with West Nile virus, SARS and COVID-19.

Education

[edit]Lipkin was born in Chicago, Illinois, where he attended the University of Chicago Laboratory School and was president of the student board in 1969. He relocated to New York and earned his BA from Sarah Lawrence College in 1974. At Sarah Lawrence, he "felt that if I went straight into cultural anthropology after college I'd be a parasite. I'd go someplace, take information about myths and ritual, and have nothing to offer. So I decided to become a medical anthropologist and try to bring back traditional medicines. Suddenly I found myself in medical school."[1] Returning to his hometown Chicago, Lipkin earned his MD from Rush Medical College, in 1978. He then became a clinical clerk at the UCL Institute of Neurology in Queen Square, London, on a fellowship, and an intern in Medicine at University of Pittsburgh (1978–1979). He completed a residency in Medicine at University of Washington (1979–1981), and completed a residency in Neurology at University of California, San Francisco (1981–1984). He conducted postdoctoral research in microbiology and neuroscience at The Scripps Research Institute, from 1984 to 1990, under the mentorship of Michael Oldstone and Floyd Bloom. In his six years at Scripps, Lipkin became a senior research associate upon completing his postdoctoral work, and was president of the Scripps' Society of Fellows in 1987.

Career

[edit]Lipkin has earned the reputation of a "master virus hunter" due to his speed and innovative methods of identifying new viruses, and has been lauded by National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases director Dr. Anthony S. Fauci. As director of the Center for Infection and Immunity at the Mailman School of Public Health; Lipkin, from the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, has led CII researchers collaborating with researchers at Sun Yat-sen University in China. Dr. Lipkin had also advised the Chinese government and the World Health Organization (WHO) during the 2002–2004 SARS outbreak.[2][3] Dr. Lipkin described his own infection with the SARS-CoV-2 virus, beginning mid-March 2020, which resulted in a case of COVID-19 and necessitated his recovering from the illness at home, on the podcast This Week in Virology.[4]

Lipkin was the Louise Turner Arnold Chair in the Neurosciences[5] at the University of California, Irvine from 1990 to 2001 and was recruited shortly thereafter by Columbia University. He began his current tenure at Columbia as the founding director of the Jerome L. and Dawn Greene Infectious Disease Laboratory from 2002 to 2007, which transitioned to the John Snow Professorship he holds at present.

A physician-scientist, Lipkin is internationally recognized for his work with West Nile virus and SARS, as well as advancing pathogen discovery techniques by developing a staged strategy using techniques pioneered in his lab. These molecular biological methods, including MassTag-PCR, the GreeneChip diagnostic, and High Throughput Sequencing, are a major step towards identifying and studying new viral pathogens that emerge locally throughout the globe. A major node in a global network of investigators working to address the challenges of pathogen surveillance and discovery, Dr. Lipkin has trained over 30 internationally based scientists in these state-of-the art diagnostic techniques.

Lipkin is the director for the Center for Research in Diagnostics and Discovery, under the National Institutes of Health Centers of Excellence for Translational Research program.[6] The Center for Research brings together leading investigators in microbial and human genetics, engineering, microbial ecology and public health to develop insights into mechanisms of disease and methods for detecting infectious agents, characterizing microflora and identifying biomarkers that can be used to guide clinical management. Lipkin was previously the Director of the Northeast Biodefense Center,[7] the Regional Center of Excellence in Biodefense and Emerging Infectious Diseases which comprised 28 private and public academic and public health institutions in New York, New Jersey and Connecticut. Within this consortium, his research focused on pathogen discovery, using unexplained hemorrhagic fever, febrile illness, encephalitis, and meningoencephalitis as targets. He is the Principal Investigator of the Autism Birth Cohort, a unique international program that investigates the epidemiology and basis of neurodevelopmental disorders through analyses of a prospective birth cohort of 100,000 children and their parents. The ABC is examining gene-environment-timing interactions, biomarkers and the trajectory of normal development and disease. Lipkin also directs the World Health Organization Collaborating Centre for Diagnostics in Zoonotic and Emerging Infectious Diseases, the only academic center, and one of two in the US (the other is CDC), that participates in outbreak investigation for the WHO.

Lipkin was co-chair of CDC Steering Committee of the National Biosurveillance Advisory Subcommittee (NBAS).[8] The NBAS was established in response to Homeland Security Presidential Directive 21 (HSPD-21),[9] "Public Health and Medical Preparedness."

He is Honorary Director of the Beijing Infectious Disease Center, Chair of the Scientific Advisory Board of the Institut Pasteur de Shanghai and serves on boards of the Australian Biosecurity Cooperative Research Centre for Emerging Infectious Disease, the Guangzhou Institute for Biomedicine and Health, the EcoHealth Alliance,[10] Tetragenetics, and 454 Life Sciences Corporation.

Lipkin served as a science consultant for the film Contagion.[11] The film has been praised for its scientific accuracy.

Early career

[edit]While not quite a medical anthropologist, Lipkin specializes in infectious diseases and their neurological impact. His first professional publication came in 1979 during the time of his fellowship in London as a letter to the Editor at the Archives of Internal Medicine (now JAMA Internal Medicine), where he poses a potential correlation between eosinopenia and bacteremia in diagnostic evaluations for a bacteremic patient.[12] While at UCL, he worked with John Newsom-Davis, who was utilizing plasmapheresis to better understand myasthenia gravis, a neuromuscular disease.[13]

In 1981, Lipkin began his neurology residency and worked in a local San Francisco clinic, which was about the time AIDS began to affect the local city population. Because of the social view of homosexual people at the time, very few clinicians would see patients with these symptoms. He "was watching many patients fall ill with AIDS. It took years for scientists to discover the virus responsible for the disease... 'I saw all of this, and I said, 'We have to find new and better ways to do this.'"[14] It was during this epidemic that Lipkin took the approach of looking for a virus' genes instead of looking for antibodies in infected people as a way to speed up the diagnosis process. By the mid-1980s, Lipkin had published two papers specifically about AIDS research[15][16] and transitioned into utilizing a more pathological approach to virus identification. He identified AIDS-associated immunological abnormalities and inflammatory neuropathy, which he showed could be treated with plasmapheresis and demonstrated early life exposure to viral infections affects neurotransmitter function.

Bornavirus

[edit]In 1989, Lipkin was the first to identify a microbe using purely molecular tools.[17][18] During his time as Chair at UC Irvine, Lipkin published several papers throughout the decade dissecting and interpreting bornavirus.[19] Once it was apparent the viral infections could selectively alter behavior and steady state brain levels of neurotransmitter mRNAs, the next step was to look for infectious agents which could be used as probes to map anatomic and functional domains in the central nervous system (CNS).[20]

By the mid-1990s, it was asserted that "Borna disease is a neurotropic negative-strand RNA virus that infects a wide range of vertebrate hosts," causing "an immune-mediated syndrome resulting in disturbances in movement and behavior."[21] This led to several groups across the globe working to determine if there was a link between Borna disease virus (BDV) or a related agent and human neuropsychiatric disease.[22] The group was formally called Microbiology and Immunology of Neuropsychiatric Disorders (MIND) and the multicenter, multi-national group focused on using standardized methods for clinical diagnosis and blinded laboratory assessment of BDV infection.[23] After nearly two decades of inquiry, the first blinded case-controlled study of the link between BDV and psychiatric illness[24] was completed by the researchers at Columbia University's Center for Infection and Immunity in a joint effort that concluded there is no association between the two. Lipkin noted that "it was concern over the potential role of BDV in mental illness and the inability to identify it using classical techniques that led us to develop molecular methods for pathogen discovery. Ultimately these new techniques enabled us to refute a role for BDV in human disease. But the fact remains that we gained strategies for the discovery of hundreds of other pathogens that have important implications for medicine, agriculture, and environmental health."[25]

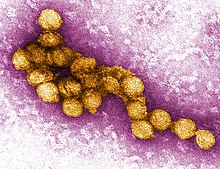

West Nile Virus

[edit]

In 1999, West Nile virus was reported in two patients in Flushing Hospital Medical Center in Queens, New York. Lipkin led the team identifying West Nile virus in brain tissue of encephalitis victims in New York State.[14] It was determined potential routes for the spread of West Nile virus throughout New York (and the Eastern United States) originated from predominantly mosquitoes, but also possible from infected birds or human beings. There is a high likelihood the two international airports nearby the initial reported cases were also the initial points of entry into the United States.[26] During the five years after the first reported case, Lipkin worked on a study with the National Institutes of Health (NIH) and the Wadsworth Center at the New York State Department of Health to determine how a vaccine could be developed. While they had some success with the immunization of mice with particles resembling the structural protein prME of West Nile Virus,[27] as of 2018, there is still no human vaccine for West Nile Virus.[28]

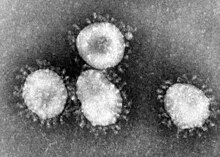

SARS-CoV

[edit]

Chinese scientists first discovered the severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) coronavirus in February 2003, but due to initial misinterpretation of the data, the information of the correct agent associated with SARS was suppressed and the outbreak investigation had a delayed start. Advanced hospital facilities were at the greatest risk as they were most susceptible to virus transmission, so it was the "classical gumshoe epidemiology" of "contact tracing and isolation" that brought swift action against the epidemic.[29] Lipkin was requested to assist with the investigation by Chen Zhou, vice president of the Chinese Academy of Sciences and Xu Guanhua, minister of the Ministry of Science and Technology in China to "assess the state of the epidemic, identify the gaps in science, and develop a strategy for containing the virus and reducing morbidity and mortality."[30] This brought the development of real-time polymerase chain reaction technology, which essentially allowed for the detection of infection at earlier time points as the process, in this instance, targets the N gene sequence and amplify the analysis in a closed system. This markedly reduces the risk of contamination during processing.[31] Test kits were developed with this PCR-based assay analysis[32] and 10,000 were hand-delivered to Beijing during the height of the outbreak by Lipkin, whereupon he trained local clinical microbiologists on the proper usage. He became ill upon his return to the U.S. and was quarantined.[33]

Lipkin was asked to join the Defense Science Board Task Force on SARS Quarantine Guidance during the height of the SARS outbreak between 2003 and 2004, to advise the U.S. Department of Defense on steps to domestically manage the epidemic. As part of the EcoHealth Alliance, Lipkin's center worked in conjunction with an NIH/NIAID grant[34] assessing bats as the reservoir for the SARS virus. 47 publications resulted from this grant, which also included assessment on Nipah, Hendra, Ebola, and Marburg viruses. This proved to be significant research on the overall study of viral reservoirs as it was determined that bats carry coronaviruses and either directly infect humans with an exchange of bodily fluid (such as a bite) or indirectly by infecting an intermediate host, such as swine.[35] Lipkin addressed a health forum in Guangzhou in January 2004 where China Daily reported him as saying: "SARS virus is probably rooted and spread by rats."[36]

In 2016, the Chinese government awarded him the International Science and Technology Cooperation Award, the nation's top science honor for foreign scientists,[37] and in January 2020, it awarded him a medal marking the People's Republic of China's 70th Anniversary, both awards for his work during the 2002–2004 SARS outbreak and in strengthening China's public health system.[38]

MERS-CoV

[edit]Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS) was first reported in Saudi Arabia during June 2012 when a local man was initially diagnosed with acute pneumonia and later died of kidney failure. The early reports of the disease were similar to SARS as the symptoms are similar, but it was quickly determined these cases were caused by a new strain called MERS coronavirus (MERS-CoV). Given Lipkin's expertise with the SARS outbreak in China nearly ten years prior, the Saudi Arabian Ministry of Health granted Lipkin and his lab local access to animal samples related to the initial reported cases.[39] With the rare opportunity, Lipkin's team created a mobile lab able to fit in six pieces of personal luggage and was transported from New York to Saudi Arabia via commercial flight to complete the analysis of samples.[40]

It seemed unlikely that bats were directly infecting humans, as the direct physical interaction between the two is limited at best.[39] A study was completed in more local proximity, examining the diverse bat populations in southeastern Mexico and determining how diverse the viruses they carry could be.[41] However, it became apparent that dromedary camels were the intermediary in the transmission between bats and humans, since camel milk and meat are dietary staples in the Saudi Arabian region.[42] The instances of human-to-human transmission appeared to be isolated to case-patients and anyone in close direct contact with them, as opposed to a broad open-air transmission.[43] By 2017, it was determined that bats are most likely the evolutionary original source for MERS-CoV along with several other coronaviruses, though not all of those types of zoonotic viruses are direct threats to humans like MERS-CoV[44] and "[c]ollectively, these examples demonstrate that the MERS-related coronaviruses are high associated with bats and are geographically widespread."[45]

Myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome

[edit]Myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS) is a chronic condition characterized by extreme fatigue after exertion that is not relieved by rest and includes other symptoms, such as muscle and joint pain and cognitive dysfunction. In September 2017, the NIH awarded a $9.6 million grant to Columbia University for the "CfS for ME/CFS" intended for the pursuit of basic research and the development of tools to help both physicians and patients effectively monitor the course of the illness.[46] This collaboration effort led by Lipkin includes other institutions, such as the Bateman Horne Center (Lucinda Bateman), Harvard University (Anthony L. Komaroff), Stanford University (Kegan Moneghetti), Sierra Internal Medicine (Daniel Peterson), University of California, Davis (Oliver Fiehn), and Albert Einstein College of Medicine (John Greally), along with private clinicians in New York City.[47]

The team of researchers and clinicians initially collaborated to de-link xenotropic murine leukemia virus-related virus (XMRV) to ME/CFS after the NIH requested research into the conflicting reports between XMRV and ME/CFS. The group "consolidated its vision with support from the Hutchins Family Foundation Chronic Fatigue Initiative and a crowd-funding organization, The Microbe Discovery Project, to explore the role of infection and immunity in disease and identify biomarkers for diagnosis through functional genomic, proteomic, and metabolomic discovery."[48] The project will collect a large clinical database and sample repository representing oral, fecal, and blood samples from well-characterized ME/CFS subjects and frequency-matched controls collected nationwide over a period of several years. Additionally, researchers are working with ME/CFS community and advocacy groups as the project progresses.[49]

Acute flaccid myelitis (AFM)

[edit]Acute flaccid myelitis (AFM) is a serious condition of the spinal cord with symptoms including rapid onset of arm or leg weakness, decreased reflexes, difficulty moving the eyes, speaking, or swallowing may also occur. Occasionally numbness or pain may be present and complications can include trouble breathing. In August 2019, Lipkin and Dr. Nischay Mishra published a collaborative study with the CDC in analyzing serological data for serum and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) samples of AFM patients.[50] The Lipkin team utilized high-density peptide arrays (also known as Serochips) to identify antibodies to EV-D68 in those samples. The technology was featured on the Dr. Oz Show in mid-September, illustrating how the enterovirus affects the CSF and the actual Serochip used to do the analysis.[51][52] In October, the University of California, San Francisco published a separate collaborative study with the CDC that confirmed the presence of antibodies to enterovirus in AFM patient CSF samples using phage display (VirScan).[53] "It's always good to see reproducibility. It gives more confidence in the findings for sure," commented Lipkin in an October 2019 CNN article. "This gives us more support of what we found."[54][55][56]

SARS-CoV-2

[edit]According to the Financial Times, Lipkin first learnt of COVID-19 from contacts in China, where it first emerged, in mid-December.[57] In early January he repeatedly urged his Chinese counterparts to publish the virus's genetic sequencing to aid research, and visited senior Chinese officials, including Premier Li Keqiang,[58] to discuss the disease. Lipkin described his engagement with the early COVID-19 investigations during an April 2023 interview with the U.S. House of Representatives Select Committee on the Coronavirus Pandemic.[59]

On January 29, 2020, Lipkin flew into Guangzhou, China to learn about the outbreak of SARS-CoV-2.[60] Lipkin met with the epidemiologist and pulmonologist Zhong Nanshan,[61] the lead advisor to the Chinese government during the outbreak.[62] Lipkin also worked with the China CDC to access blood samples from across the country for further study into the origin and spread of the virus.[63] Lipkin did not travel to Wuhan, the epicenter of the outbreak, due to fears that this would prevent him from returning to the United States.[64] On returning to the United States, Lipkin self-quarantined for 14 days.[65] Lipkin later contracted SARS-CoV-2 in New York City,[66] refusing to go to hospital and treating himself with hydroxychloroquine at home.[57]

Lipkin criticized what he considered a xenophobic response that blames China for the virus, specifically the words of US president Donald Trump calling it the "China virus" and his decision to suspend funding to the World Health Organization for being "China-centric", calling for "global problems" to be addressed by "global solutions". He said that a series of government missteps helped spread the virus around the world very rapidly, and criticized the US and UK's responses, calling them slow, and blamed insufficient and inadequate testing and tracing for rising fatality numbers. In the US, he singled out as an issue what he saw as an inconsistency in advice, including by president Trump, and highlighted the need for national leadership, while acknowledging states had the ability to make decisions in certain areas. He praised his NIAID superior Anthony Fauci for his integrity. He also warned about the danger of future emergence of new deadly viruses.[57]

After his trip to China, Lipkin maintained links with Lu Jiahai, his research partner at Sun Yat-sen University in Guangzhou, and Zhong Nanshan, to try to establish the origins of the virus.[61] Their efforts, aimed at finding out whether the virus emerged in other parts of China and circulated before it was first discovered in Wuhan in December, include antibody tests of nationwide blood bank samples from pneumonia patients which predate the pandemic, which led to a collaboration with the Chinese Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.[58] According to Lipkin, this research began in early February. The international research team also began studying blood samples from different wild animals which it deemed potential origins of the virus, in order to understand animal-to-human transmission.[58]

Lipkin thinks the virus could have originated in the wild animal trade and undergone "repeated jumps" from animal to human in the weeks before the first cases were logged, such a stream of events having recent precedents in the emergence of MERS-CoV, which jumped from dromedary camels to humans in 2012, and SARS-CoV, from civet cats to humans in 2003.[57]

Lipkin co-authored a paper on "The proximal origin of SARS-CoV-2", which was published in Nature Medicine in March 2020.[67] The conclusion of the genomic analyses was that COVID-19 was not a case of lab leak or human-made infection. In 2023, the paper was alleged by the US Republicans as a coverup based on certain misconducts to eliminate the lab leak theory. The paper and the controversy became known as the "Proximal Origin".[68][69]

Views on gain-of-function research

[edit]This section appears to be slanted towards recent events. (August 2021) |

Gain-of-function experiments aim to increase the virulence and/or transmissibility of pathogens, in order to better understand them and inform public health preparedness efforts.[70] This includes targeted genetic modification (to create hybrid viruses), the serial passaging of a virus through a host animal (to generate adaptive mutations), and targeted mutagenesis (to introduce mutations).[71] Lipkin is a listed "supporter" of the gain-of-function advocate group, Scientists for Science,[72] which was co-founded by Columbia colleague Vincent Racaniello.[73] The US National Institutes of Health placed a moratorium on gain-of-function research in October 2014, and lifted the moratorium in December 2017, after the implementation of stricter controls.[74][75]

Lipkin, while not endorsing every gain-of-function experiment, has said that "[t]here clearly are going to be instances where gain-of-function research is necessary and appropriate." In the example of Ebola, which is incapable of airborne transfer, Lipkin believes that "researchers could make a case for the need to determine how the virus could evolve in nature by engineering a more dangerous version in the lab." Lipkin believes that there should be guidelines in place to govern gain-of-function experiments.[76] Lipkin has called for the World Health Organization to establish strict biocontainment criteria that can be applied globally – including in the developing world – to gain-of-function research.[77]

Selected awards and honors

[edit]| Year(s) | Award/Honor | Institution/Organization |

|---|---|---|

| 2020 | PRC 70th Anniversary Medal[38] | Chinese Central Government, Central Military Commission, and State Council |

| 2016 | China International Science and Technology Cooperation Award[78] | People's Republic of China |

| 2015 | Fellow[79] | Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) |

| 2010 | Member[80] | Association of American Physicians (AAP) |

| 2008 | John Snow Professor of Epidemiology[79] | Columbia University |

| 2006 | Fellow[80] | American Society for Microbiology (ASM) |

| 2004 | Fellow[80] | New York Academy of Sciences |

| 2003 | Special Advisor to the Ministry of Science and Technology[81] | People's Republic of China |

| 1986-87 | President, Society of Fellows[82] | Scripps Research Institute |

References

[edit]- ^ "Ian Lipkin The Virus Hunter" (PDF). Discover. April 2012.

- ^ Zimmer, Carl (November 22, 2010). "A Man From Whom Viruses Can't Hide". The New York Times. Retrieved March 24, 2020.

- ^ Kim, Elizabeth (February 3, 2020). "NYC Team Led By Scientist Who Advised On "Contagion" Is Racing To Unlock The Coronavirus. Here's What They Told Us". Gothamist. New York Public Radio. Archived from the original on February 4, 2020. Retrieved March 24, 2020.

- ^ This Week in Virology (TWiV) podcast.28 March 2020 http://www.microbe.tv/twiv/twiv-special-lipkin/

- ^ Gewertz, Catherine (March 31, 1993). "Realtor to Give $1.62 Million for UCI Chair". Los Angeles Times.

- ^ "Centers of Excellence for Translational Research". nih.gov.

- ^ "Northeast Biodefense Center". njms.rutgers.edu. Rutgers New Jersey Medical School. Retrieved August 28, 2021.

- ^ "Dr. W. Ian Lipkin Named Co-Chair of CDC Subcommittee". 15 July 2010.

- ^ "Homeland Security Presidential Directive". archives.gov. 18 October 2007.

- ^ "Home - EcoHealth Alliance". ecohealthalliance.org.

- ^ "Five Questions for Ian Lipkin, the Scientist Who Designed Contagion's Virus". 9 September 2011.

- ^ Lipkin, W. I. (April 1979). "Eosinophil Counts in Bacteremia" (PDF). Archives of Internal Medicine. 139 (4): 490–1. doi:10.1001/archinte.1979.03630410094035. PMID 435009.

- ^ Hamblin, Terry (1998). "Plasmapheresis". Encyclopedia of Immunology. pp. 1969–1971. doi:10.1006/rwei.1999.0495. ISBN 9780122267659.

- ^ a b Zimmer, Carl (November 22, 2010). "A Man From Whom Viruses Can't Hide". New York Times.

- ^ Landay, A.; Poon, M. C.; Abo, T.; Stagno, S.; Lurie, A.; Cooper, M. D. (1983). "Immunologic studies in asymptomatic hemophilia patients. Relationship to acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS)" (PDF). The Journal of Clinical Investigation. 71 (5): 1500–4. doi:10.1172/JCI110904. PMC 437015. PMID 6222070.

- ^ Lipkin, W. I.; Parry, G.; Kiprov, D.; Abrams, D. (1985). "Inflammatory neuropathy in homosexual men with lymphadenopathy" (PDF). Neurology. 35 (10): 1479–83. doi:10.1212/WNL.35.10.1479. PMID 2993951. S2CID 6542995.

- ^ Lipkin, W. I.; Travis, G. H.; Carbone, K. M.; Wilson, M. C. (1990). "Isolation and characterization of Borna disease agent cDNA clones". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 87 (11): 4184–8. Bibcode:1990PNAS...87.4184L. doi:10.1073/pnas.87.11.4184. JSTOR 2354914. PMC 54072. PMID 1693432.

- ^ Lipkin, W. I. (2010). "Microbe hunting". Microbiology and Molecular Biology Reviews. 74 (3): 363–77. doi:10.1128/MMBR.00007-10. PMC 2937520. PMID 20805403.

- ^ "1990 - 1999 | Columbia Public Health". www.publichealth.columbia.edu.

- ^ Lipkin, W. I.; Carbone, K. M.; Wilson, M. C.; Duchala, C. S.; Narayan, O.; Oldstone, M. B. (1988). "Neurotransmitter abnormalities in Borna disease". Brain Research. 475 (2): 366–70. doi:10.1016/0006-8993(88)90627-0. PMID 2905625. S2CID 8893525.

- ^ Briese, T.; Schneemann, A.; Lewis, A. J.; Park, Y. S.; Kim, S.; Ludwig, H.; Lipkin, W. I. (1994). "Genomic organization of Borna disease virus". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 91 (10): 4362–6. Bibcode:1994PNAS...91.4362B. doi:10.1073/pnas.91.10.4362. PMC 43785. PMID 8183914.

- ^ Bode, L.; Ludwig, H. (2003). "Borna Disease Virus Infection, a Human Mental-Health Risk". Clinical Microbiology Reviews. 16 (3): 534–545. doi:10.1128/CMR.16.3.534-545.2003. PMC 164222. PMID 12857781.

- ^ Lipkin, W. I.; Hornig, M.; Briese, T. (2001). "Borna disease virus and neuropsychiatric disease--a reappraisal". Trends in Microbiology. 9 (7): 295–8. doi:10.1016/S0966-842X(01)02071-6. PMID 11435078.

- ^ Hornig, M.; Briese, T.; Licinio, J; Khabbaz, R. F.; Altshuler, L. L; Potkin, S. G.; Schwemmle, M.; Siemetzki, U; Mintz, J.; Honkavuori, K; Kraemer, H. C.; Egan, M. F.; Whybrow, P. C.; Bunney, W. E; Lipkin, W. I. (2012). "Absence of evidence for bornavirus infection in schizophrenia, bipolar disorder and major depressive disorder". Molecular Psychiatry. 17 (5): 486–93. doi:10.1038/mp.2011.179. PMC 3622588. PMID 22290118.

- ^ "Does Borna Disease Virus Cause Mental Illness? | Columbia Public Health". www.publichealth.columbia.edu. January 31, 2012.

- ^ Briese, T.; Jia, X. Y.; Huang, C.; Grady, L. J.; Lipkin, W. I. (1999). "Identification of a Kunjin/West Nile-like flavivirus in brains of patients with New York encephalitis". Lancet. 354 (9186): 1261–1262. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(99)04576-6. PMID 10520637. S2CID 5469505.

- ^ Qiao, M.; Ashok, M.; Bernard, K. A.; Palacios, G.; Zhou, Z. H.; Lipkin, W. I.; Liang, T. J. (2004). "Induction of sterilizing immunity against West Nile Virus (WNV), by immunization with WNV-like particles produced in insect cells". The Journal of Infectious Diseases. 190 (12): 2104–2108. doi:10.1086/425933. PMID 15551208.

- ^ "Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: West Nile Virus". 3 June 2020.

- ^ Lipkin, W. Ian (2009). "SARS: How a global epidemic was stopped". Global Public Health. 4 (5): 500–501. doi:10.1080/17441690903061389. S2CID 71513132.

- ^ "Ian Lipkin Receives Top Science Honor in China | Columbia Public Health". www.publichealth.columbia.edu.

- ^ Zhai, J.; Briese, T.; Dai, E.; Wang, X.; Pang, X.; Du, Z.; Liu, H.; Wang, J.; Wang, H.; Guo, Z.; Chen, Z.; Jiang, L.; Zhou, D.; Han, Y.; Jabado, O.; Palacios, G.; Lipkin, W. I.; Tang, R. (2004). "Real-time polymerase chain reaction for detecting SARS coronavirus, Beijing, 2003". Emerging Infectious Diseases. 10 (2): 300–303. doi:10.3201/eid1002.030799. PMC 3322935. PMID 15030701.

- ^ "Columbia University Technology Ventures, submission date April 15, 2003".

- ^ "W. Ian Lipkin, MD | Columbia Public Health". www.mailman.columbia.edu.

In 2003, Lipkin sequenced a portion of the SARS virus directly from lung tissue [...]. He became ill shortly after returning to the US and was quarantined.

- ^ "Risk of Viral Emergence from Bats - Dimensions". app.dimensions.ai.

- ^ Quan, P. L.; Firth, C.; Street, C.; Henriquez, J. A.; Petrosov, A.; Tashmukhamedova, A.; Hutchison, S. K.; Egholm, M.; Osinubi, M. O.; Niezgoda, M.; Ogunkoya, A. B.; Briese, T.; Rupprecht, C. E.; Lipkin, W. I. (2010). "Identification of a severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-like virus in a leaf-nosed bat in Nigeria". mBio. 1 (4). doi:10.1128/mBio.00208-10. PMC 2975989. PMID 21063474.

- ^ "Back on SARS standby". www.chinadaily.com.cn. Retrieved 2020-06-12.

- ^ "Ian Lipkin Receives Top Science Honor in China | Columbia Public Health". www.publichealth.columbia.edu. Mailman School of Public Health, Columbia University. January 8, 2016. Retrieved 2020-11-24.

- ^ a b "China Honors Ian Lipkin | Columbia Public Health". www.publichealth.columbia.edu. Mailman School of Public Health, Columbia University. January 7, 2020. Retrieved 2020-11-24.

- ^ a b "Bat Out of Hell? Egyptian Tomb Bat May Harbor MERS Virus". 22 August 2013.

- ^ "Meet the World's Top Virus Hunter". Gizmodo. 7 March 2014.

- ^ Anthony, S. J.; Ojeda-Flores, R.; Rico-Chávez, O.; Navarrete-Macias, I.; Zambrana-Torrelio, C. M.; Rostal, M. K.; Epstein, J. H.; Tipps, T.; Liang, E.; Sanchez-Leon, M.; Sotomayor-Bonilla, J.; Aguirre, A. A.; Ávila-Flores, R.; Medellín, R. A.; Goldstein, T.; Suzán, G.; Daszak, P.; Lipkin, W. I. (2013). "Coronaviruses in bats from Mexico". The Journal of General Virology. 94 (Pt 5): 1028–1038. doi:10.1099/vir.0.049759-0. PMC 3709589. PMID 23364191.

- ^ "Will MERS become a global threat?". CNN. 20 May 2014.

- ^ Memish, Z. A.; Mishra, N.; Olival, K. J.; Fagbo, S. F.; Kapoor, V.; Epstein, J. H.; Alhakeem, R.; Durosinloun, A.; Al Asmari, M.; Islam, A.; Kapoor, A.; Briese, T.; Daszak, P.; Al Rabeeah, A. A.; Lipkin, W. I. (2013). "Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus in bats, Saudi Arabia". Emerging Infectious Diseases. 19 (11): 1819–23. doi:10.3201/eid1911.131172. PMC 3837665. PMID 24206838.

- ^ Anthony, S. J.; Gilardi, K.; Menachery, V. D.; Goldstein, T.; Ssebide, B.; Mbabazi, R.; Navarrete-Macias, I.; Liang, E.; Wells, H.; Hicks, A.; Petrosov, A.; Byarugaba, D. K.; Debbink, K.; Dinnon, K. H.; Scobey, T.; Randell, S. H.; Yount, B. L.; Cranfield, M.; Johnson, C. K.; Baric, R. S.; Lipkin, W. I.; Mazet, J. A. (2017). "Further Evidence for Bats as the Evolutionary Source of Middle East Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus". mBio. 8 (2). doi:10.1128/mBio.00373-17. PMC 5380844. PMID 28377531.

- ^ "MERS-like coronavirus identified in Ugandan bat: New virus not likely to spread to humans". ScienceDaily.

- ^ "NIH Awards $9.6 Million Grant to Columbia for a Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome Collaborative Research Center | Columbia Public Health". www.publichealth.columbia.edu.

- ^ "Who We Are | Columbia Public Health". www.publichealth.columbia.edu.

- ^ "Center for Solutions for ME/CFS". reporter.nih.gov. Retrieved August 28, 2021.

- ^ "NIH announces centers for myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome research | National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke". www.ninds.nih.gov.

- ^ Mishra, N; Ng, TFF; Marine, RL; Jain, K; Ng, J; Thakkar, R; Caciula, A; Price, A; Garcia, JA; Burns, JC; Thakur, KT; Hetzler, KL; Routh, JA; Konopka-Anstadt, JL; Nix, WA; Tokarz, R; Briese, T; Oberste, MS; Lipkin, WI (13 August 2019). "Antibodies to Enteroviruses in Cerebrospinal Fluid of Patients with Acute Flaccid Myelitis". mBio. 10 (4): e01903-19. doi:10.1128/mBio.01903-19. PMC 6692520. PMID 31409689.

- ^ "Hear Firsthand From the Doctor Who is Getting Closer to Finding a Cure for AFM". The Dr. Oz Show. 16 September 2019. Retrieved 12 November 2019.

- ^ "How Researchers Figured Out What Causes AFM". The Dr. Oz Show. 16 September 2019. Retrieved 12 November 2019.

- ^ Schubert, RD; Hawes, IA; Ramachandran, PS; Ramesh, A; Crawford, ED; Pak, JE; Wu, W; Cheung, CK; O'Donovan, BD; Tato, CM; Lyden, A; Tan, M; Sit, R; Sowa, GA; Sample, HA; Zorn, KC; Banerji, D; Khan, LM; Bove, R; Hauser, SL; Gelfand, AA; Johnson-Kerner, BL; Nash, K; Krishnamoorthy, KS; Chitnis, T; Ding, JZ; McMillan, HJ; Chiu, CY; Briggs, B; Glaser, CA; Yen, C; Chu, V; Wadford, DA; Dominguez, SR; Ng, TFF; Marine, RL; Lopez, AS; Nix, WA; Soldatos, A; Gorman, MP; Benson, L; Messacar, K; Konopka-Anstadt, JL; Oberste, MS; DeRisi, JL; Wilson, MR (21 October 2019). "Pan-viral serology implicates enteroviruses in acute flaccid myelitis". Nature Medicine. 25 (11): 1748–1752. doi:10.1038/s41591-019-0613-1. PMC 6858576. PMID 31636453.

- ^ "Virus could be the cause of mysterious polio-like illness AFM, study says". CNN Health. 21 October 2019. Retrieved 12 November 2019.

- ^ "What Causes a Mysterious Paralysis in Children? Researchers Find Viral Clues". The New York Times. 21 October 2019. Retrieved 12 November 2019.

- ^ "Evidence links poliolike disease in children to a common type of virus". Science Magazine. 21 October 2019. Retrieved 12 November 2019.

- ^ a b c d Manson, Katrina (April 17, 2020). "Virologist behind 'Contagion' film criticises leaders' slow responses". Financial Times. Washington. Retrieved 2020-11-24.

- ^ a b c Manson, Katrina; Sun, Yu (April 27, 2020). "US and Chinese researchers team up for hunt into Covid origins". Financial Times. Retrieved 2020-11-22.

- ^ "Transcribed Interview with Dr. Ian Lipkin". United States House Committee on Oversight and Accountability. 2023-07-11. Retrieved 2023-07-20.

- ^ Weintraub, Karen (12 February 2020). "Epidemiologist Veteran of SARS and MERS Shares Coronavirus Insights after China Trip". Scientific American. Retrieved 16 June 2020.

- ^ a b Guo, Rui; Zhuang, Pinghui (2020-05-27). "Covid-19 origin research hit by political agendas: 'Sars hero'". South China Morning Post. Guangzhou and Beijing. Retrieved 2020-11-24.

- ^ "Our Experts Respond to the Coronavirus Outbreak". 4 February 2020. Retrieved 2 July 2020.

- ^ Manson, Katrina; Yu, Sun (27 April 2020). "US and Chinese researchers team up for hunt into Covid origins". Financial Times. Retrieved 16 June 2020.

- ^ Stankiewicz, Kevin (10 February 2020). "Scientists worry coronavirus could evolve into something worse than flu, says quarantined expert". CNBC. Retrieved 2 July 2020.

- ^ Paumgarten, Nick (1 March 2020). "A Local Guide to the Coronavirus". The New Yorker. Retrieved 2 July 2020.

- ^ Stankiewicz, Kevin (31 March 2020). "Infectious disease expert who has coronavirus says public health can not be overlooked again". CNBC. Retrieved 2 July 2020.

- ^ Andersen, Kristian G.; Rambaut, Andrew; Lipkin, W. Ian (March 17, 2020). "The proximal origin of SARS-CoV-2". Nature Medicine. 26 (4). Springer Nature Limited: 450–452. doi:10.1038/s41591-020-0820-9. PMC 7095063. PMID 32284615.

- ^ Stolberg, Sheryl Gay; Mueller, Benjamin (2023-07-11). "Scientists, Under Fire From Republicans, Defend Fauci and Covid Origins Study". The New York Times. Retrieved 2023-08-12.

- ^ Jon, Cohen (2023-07-11). "Politicians, scientists spar over alleged NIH cover-up using COVID-19 origin paper". Science. doi:10.1126/science.adj7036.

- ^ Selgelid, Michael J. (2016). "Gain-of-Function Research: Ethical Analysis". Science and Engineering Ethics. 22 (4): 923–964. doi:10.1007/s11948-016-9810-1. ISSN 1353-3452. PMC 4996883. PMID 27502512.

- ^ "Gryphon Report, Final Draft, Analysis of Gain-of-Function Research, Dec, 2015, p43-45" (PDF).

- ^ "Scientists for Science". www.scientistsforscience.org. Retrieved 2020-06-10.

- ^ Roos, Robert (July 30, 2014). "Scientists voice support for research on dangerous pathogens". CIDRAP. Retrieved 2020-06-10.

- ^ Reardon, Sara (19 December 2017). "US government lifts ban on risky pathogen research". Nature. Retrieved 2 July 2020.

- ^ Burki, Talha (2018-02-01). "Ban on gain-of-function studies ends". The Lancet Infectious Diseases. 18 (2): 148–149. doi:10.1016/S1473-3099(18)30006-9. ISSN 1473-3099. PMC 7128689. PMID 29412966.

- ^ Reardon, Sara (23 October 2014). "U.S. Suspends Risky Disease Research". Nature. 514 (7523): 411–2. Bibcode:2014Natur.514..411R. doi:10.1038/514411a. PMID 25341765. S2CID 4448945. Retrieved 2020-06-10.

- ^ Lipkin, W. Ian (2012-11-01). "Biocontainment in Gain-of-Function Infectious Disease Research". mBio. 3 (5). doi:10.1128/mBio.00290-12. ISSN 2150-7511. PMC 3484385. PMID 23047747.

- ^ "Ian Lipkin Receives Top Science Honor in China | Columbia Public Health". www.publichealth.columbia.edu.

- ^ a b "Dr. W Ian Lipkin, Center for Infection & Immunity | Columbia Public Health". www.publichealth.columbia.edu.

- ^ a b c Dual Use Research of Concern in the Life Sciences: Current Issues and Controversies. 2017-09-01. p. 87. ISBN 9780309458917.

- ^ "mBio Professional Profile: Board of Editors, W. Ian Lipkin, MD". Archived from the original on 2018-06-19. Retrieved 2018-06-13.

- ^ "Oral history interview with W. Ian Lipkin". Science History Institute Digital Collections.

External links

[edit] Quotations related to W. Ian Lipkin at Wikiquote

Quotations related to W. Ian Lipkin at Wikiquote- Official website

- Ian Lipkin at IMDb