Ian Heslop

Ian Heslop | |

|---|---|

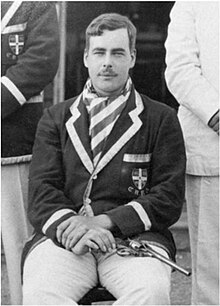

Heslop, photographed in 1926 as part of a Cambridge University shooting team in the colours of the Cambridge University Rifle Association | |

| Born | Ian Robert Penicuick Heslop June 1904 |

| Died | 2 June 1970 (aged 65) |

| Nationality | British |

| Other names | "The Purple Emperor" (nickname) |

| Education | |

| Occupations |

|

| Known for | Conservation and collecting, especially of butterflies and the pygmy hippopotamus |

| Notable work | Notes & Views of the Purple Emperor (with G.E. Hyde and R.E. Stockley) |

| Spouse | Eileen Huxford |

Ian Robert Penicuick Heslop (June 1904 – 2 June 1970) was a British naturalist, lepidopterologist and marksman. He is particularly known for his studies of the butterfly Apatura iris (purple emperor), and for his discovery of the Nigerian subspecies of the pygmy hippopotamus, named Choeropsis liberiensis heslopi after him.

Born in India in 1904, Heslop grew up in Bristol, where he studied at Clifton College. His father, a soldier and keen butterfly collector, encouraged his early interest in butterflies. Heslop continued this pursuit at Cambridge University, where he studied classics and became a successful rifle and revolver shot. He donated two trophies for varsity shooting matches – one of which is still named in his honour – between the universities of Oxford and Cambridge.

Heslop entered the Colonial Service in 1929 and became an administrator in the Owerri province of Nigeria, where he became a prolific hunter and documented what may be the last reliable sightings of Choeropsis liberiensis heslopi. He returned to England in 1952, where he taught Latin in various preparatory schools until his retirement in 1969. He was also involved in the establishment of several nature reserves, and frequently appeared on British radio to discuss nature.

Heslop's biographer, Matthew Oates, describes him as "one of the most successful collectors of British butterflies".[1] He was regarded as a leading authority on the history of British butterflies and a particular expert on Maculinea arion (large blue), of which he discovered or rediscovered several British populations. He wrote most of Notes and Views of the Purple Emperor, a 1964 collection of papers on Apatura iris, which Oates has called "a meditation on [his] all-pervading passion".[2]

Early life and education

[edit]Ian Robert Penicuick Heslop was born in India in 1904, shortly after 2 June.[3][4] His father, Septimus, served in the British Army as part of the Royal Engineers.[5] Heslop grew up in Bristol,[6] where he attended Clifton College, a public school in the city.[5] He also had family connections to Scotland.[7]

Septimus Heslop was a keen butterfly collector.[6] According to Oates's biography, the younger Heslop first began to collect butterflies at the age of seven, when a family member gave him a jar of Pieris larvae to keep him entertained through a bout of mumps. His mother subsequently forbade him from collecting: two years later, however, Septimus returned from service in India and permitted his son to resume the hobby.[5] On his eleventh birthday, he collected his first Vanessa cardui (painted lady) using a net owned by his uncle, a vicar, who used it to catch bats in his church.[2]

At Clifton, a number of pupils interested in butterfly collecting attended the school's Scientific Society, which was allowed on periodic afternoons to take trips to collect specimens. He saw his first Apatura iris (purple emperor) in 1918, at Brockley Warren in Somerset.[8] In 1921, he made what Oates calls "his first major capture", that of a Nymphalis antiopa (Camberwell beauty) in the Forest of Dean. In 1923, he visited the New Forest, a noted site for butterfly collecting, for the first time, with his father.[5]

Cambridge University

[edit]Heslop's parents intended for him to follow his father into the Royal Engineers, though Heslop himself aspired to a career in zoology or as a museum curator; the family therefore compromised on sending him to Cambridge University with a view to a post in either the civil service or colonial administration.[5] The journalist Benedict Le Vay described him as "among the pleasantly battiest of 20th-century Cambridge eccentrics".[9]

Heslop went up to Cambridge in 1923,[6] where he read classics at Corpus Christi College[10] and was a member of the Officers' Training Corps.[11] He met and befriended Charles de Worms, then studying at King's College, who would become a noted lepidopterologist and Heslop's long-time friend and collecting companion.[5] Heslop and de Worms often travelled to nearby Wicken Fen and the woods near Huntingdon in search of specimens.[12] Heslop secured what Oates calls a "good" MA, despite spending much of his final year collecting butterflies.[5]

Heslop was a prominent member of the Cambridge University Small Bore Club (CUSBC), which took part in smallbore rifle shooting: he helped Cambridge to back-to-back victories in the annual varsity match against Oxford University between 1923 and 1926. He received his blue in shooting,[a] and was CUSBC's captain in 1926.[6] He was also a prominent revolver shot: in 1929, Heslop presented the trophy awarded ever since for the varsity match in revolver shooting, which was known as the "Heslop Match" until 1948.[14][b] He also donated the trophy for the smallbore varsity match, which continues to be known as the Heslop.[16]

Colonial service

[edit]

After graduating in 1926, Heslop spent the summer of 1927 on excursions to collect butterflies, then returned to Cambridge in 1928 for a course in colonial administration. On 3 July 1929, he left for Nigeria,[17] then a British colony, to take up a position with the Nigerian Administration Services as part of the British Colonial Service.[16] He was stationed in the southern province of Owerri, where he rose to the rank of district commissioner.[16] His duties in Nigeria included presiding over legal cases: he acted as a magistrate in trials of local people charged with slave trading, and was once required to supervise an execution.[18]

Heslop learned to speak the Igbo language, and became an expert in local wildlife as well as a prolific hunter,[19] acquiring the nickname "King of the Hunters". He took part in local ceremonies,[20] but wrote unfavourably of the people of his district in a report to his British superiors about the Nkalu people:

The Nkalus are on the whole not likeable people. Their extraordinary deceitfulness and lack of good faith towards each other is their most repulsive characteristic. They are, however, free from the vulgarity that so defiles the more sophisticated communities of this province.[21]

Heslop took leave twice a year to return to England, usually over the main butterfly-collecting season.[17] He kept up closely with publications on British butterflies while in Nigeria,[22] and wrote the first edition of his Check-List of the British Lepidoptera there, with little access to libraries or museums.[17] Despite these difficulties, the Check-List was considered a standard work of lepidopterology by the 1970s.[4] Heslop considered, though never completed, writing a book on his time in Nigeria;[19] he later described this period as the happiest in his life.[18]

While in Nigeria during the early 1940s, Heslop met and married Eileen Huxford, a Church of England missionary: the two were engaged in 1942.[17] Huxford took up shooting and butterfly collecting after meeting Heslop, and went with him on hunting expeditions.[23] In 1951, finding it difficult to raise a family in Nigeria, Eileen and their children returned to England.[20] They lived in Burnham-on-Sea in Somerset, which would be Heslop's family home for the remainder of his life.[17]

Study of the Nigerian pygmy hippopotamus (Choeropsis liberiensis heslopi)

[edit]

Heslop has been described as a "key player" in the history of the pygmy hippopotamus, a species known by the name ogomogo in his jurisdiction.[6] Before the 1940s, western naturalists generally considered that the animals could not be found in Nigeria, since the nearest generally-recognised population was in Liberia, around 1,000 miles (1,600 km) to the west.[24] Heslop made his first report of the existence of the species in Nigeria in 1934.[23]

However, his observations were frequently disbelieved in the academic community.[25] He shot two of the animals in 1935 and sent their skulls to the British Museum (Natural History) in London for scientific study.[26] He shot another in 1943, and prepared the animal's entire carcass as a scientific specimen;[23] he sent its skin to the British Museum in 1968, and it was used by the naturalist Gordon Barclay Corbet to demonstrate that the Nigerian pygmy hippopotamus was indeed a distinct subspecies from the Liberian (Choeropsis liberiensis liberiensis). Corbet assigned the Nigerian subspecies to the genus Hexaprotodon[c] and named the subspecies heslopi in Heslop's honour.[28]

Heslop had intended the specimens he took to serve as evidence of the existence of the subspecies,[20] which he believed to be on the verge of extinction.[20] In 1945, he estimated that no more than thirty of the animals remained, divided between small, isolated populations.[29] He also ate meat from the animal, describing its taste as "intermediate between beef and pork".[18] He counted the skull and jaw of his third hippopotamus among his most prized possessions, and kept them until his death, when his wife Eileen donated them to the British Museum along with his hunting records.[25]

Heslop's work with the pygmy hippopotamus remained largely unknown and uncelebrated during his lifetime.[16] In 1953, the Nigerian Inspector-General of Forests acknowledged the pygmy hippopotamus as among Nigeria's native mammals, albeit as the one with the narrowest known geographical range.[20] Heslop's reports remain the last confirmed sightings of the Nigerian subspecies,[30] and it was designated extinct on the IUCN Red List in 1994.[31] Heslop is the only person known to have written an account of Choeropsis liberiensis heslopi in the wild.[20]

Butterfly collecting

[edit]

Heslop's attitude to butterfly collecting has been described by Oates as "turning the gentle pursuit of butterflies into an extreme country sport".[5] He collected his first example of Leptidea sinapis (wood white) on the tracks at a railway station, only narrowly escaping being hit by an oncoming express train. In 1968, aged sixty-four, he waded and swam into a flooded Woodwalton Fen to collect examples of Lycaena dispar batavus (large copper).[5]

He had a particular interest in Maculinea arion (large blue); in 1949, he rediscovered the existence of the species in the Polden Hills of Somerset, and later discovered previously unknown populations of it in the Quantock Hills and near Minack Head in Cornwall.[32] In his obituary of Heslop, the naturalist John F. Burton wrote that he had probably been the greatest living authority on the distribution of the species.[4] During his time in Nigeria, he specialised in collecting butterflies of the genus Charaxes.[8] Heslop's greatest obsession, however, was with Apatura iris (purple emperor), which he called in his diary "the monarch of all the butterflies".[11] He made the suggestion that its genus name, of uncertain origin, was connected to the Ancient Greek verb apatao, meaning "I deceive".[33] He captured his first specimen of Apatura iris at Fox Hill, near Petworth in West Sussex, in July 1935, having narrowly failed to catch three during an expedition with De Worms and a Colonel Labouchere at Bignor in 1933.[34]

De Worms considered Heslop's acquisition of specimens from sixty-five species to be the most ever attained by a single person, and described Heslop as "probably the foremost authority of his day" on the history of British butterflies.[3] Among butterfly collectors, he acquired the nickname "the Purple Emperor" after Apatura iris,[35] following a tradition of ascribing to collectors the name of a particular species: de Worms, for instance, was nicknamed "the setaceous Hebrew character" after the moth Xestia c-nigrum.[5] Heslop kept thorough notes on where and how he acquired his butterflies, but refused to share detailed information about where he found rare species such as Apatura iris, for fear that other collectors would damage the sites or butterfly populations.[19]

Michael Salmon, a historian of British butterfly collecting, describes Heslop as a "[naturalist] with the blood of the old Aurelians in [his] veins", referring to the eighteenth-century pioneers of the discipline who formed London's Society of Aurelians.[36] Oates calls him "one of the last great collectors of British butterflies, and certainly the greatest of the purple emperor".[8] On Heslop's death, his wife Eileen donated his collection of British and African butterflies to the Bristol City Museum.[37] The collection included over 150 specimens of Apatura iris alone.[6][d]

Notes and Views of the Purple Emperor

[edit]Heslop published Notes and Views, originally intended as a guide to collecting Apatura iris, in 1964, alongside the naturalists George E. Hyde and Roy E. Stockley. It comprises a collection of thirty-three papers, often reprints from academic journals, of which twenty-nine were written by Heslop, three by Stockley and one by Hyde, who also provided the book's colour photographs. Heslop funded part of the publication himself, gathering the remaining funds by private subscription.[38]

Oates has described the book as "gloriously anachronistic", partly because most of the papers had been written during the early-to-mid 1950s and were already behind Heslop's own knowledge of Apatura iris, and partly owing to the archaic, classicising style of Heslop's writing: Oates judges that there is "more Latin and Greek in the book than science".[39] Reviewing the work in The Entomologist's Record and Journal of Variation, the journal's editor S. N. A. Jacobs wrote that it had "more appeal to the enthusiastic amateur than to the professional entomologist" and criticised Heslop's vagueness as to the precise locations of Apatura iris habitats, but praised the detail of the work and Hyde's photography.[40] Oates considers it "a masterpiece in obsession, a meditation on an all-pervading passion, and a literary monument to the history of butterfly collecting".[2]

Later life

[edit]

Heslop returned from Nigeria in 1952,[41] and taught Latin in six[42] British preparatory schools.[16] These schools were located in Wiltshire, Sussex, in the Cotswolds[42] and near Romsey in Hampshire, all – "providentially", as de Worms put it in his obituary of Heslop – near rich habitats of Apatura iris and other collectable butterflies.[43]

Heslop was involved in the establishment of nature reserves around the United Kingdom, including Blackmoor Copse near Salisbury and Shapwick Heath in Somerset.[16] In a 1953 essay, he protested against the policy of the Forestry Commission to replant native woodlands with fast-growing conifer trees, predicting that it would lead to the near-extinction of Apatura iris by 1975;[e] the policy was ended in 1970.[45] He raised money to purchase 46 acres (19 ha) of Blackmoor Copse in 1956, counteracting a plan to replace most of its trees with conifers, and administered it as a reserve for Apatura iris.[46]

Towards the end of his life, Heslop was a frequent panellist on Country Parliament,[12] a BBC Radio 4 show which answered listeners' questions on wildlife and the countryside.[47] He retired from teaching on 22 July 1969.[42] He fractured his hip in a fall in March 1970,[42] bringing on an embolism from which he died on 2 June 1970.[4][25]

Personal life

[edit]Heslop had one son,[41] and daughters named Margaret,[19] and Jane.[48][f] Oates describes Heslop as "a large and distinctive man, with a stentorian delivery and a voluble command of English".[1] Robinson, Flacke and Hentschel characterise him as "a solitary creature, preferring the peace and privacy of collecting on his own to the companionship of others".[19]

Selected publications

[edit]- Heslop, I.R.P.; Hyde, G.E.; Stockley, R.E. (1964). Notes & Views of the Purple Emperor. Brighton: Southern Publishing Company. OCLC 4101405.

- Heslop, I.R.P. (1938). New Bilingual Catalogue of the British Lepidoptera. London: Watkins and Doncaster. OL 16838884M.

- — (1945). "The Pygmy Hippopotamus in Nigeria". Field (Nigeria). Vol. 185. pp. 629–630.

- — (1945). Revised Indexed Check-List of the British Lepidoptera with the English Name of Each of the 2,404 Species. London: Watkins and Doncaster. OL 47768923M.

- — (1961). A New Label List of the British Macrolepidoptera. London: Watkins and Doncaster. OL 35352690W.

Footnotes

[edit]Explanatory notes

[edit]- ^ Robinson, Flacke and Hentschel say that Heslop was awarded a Full Blue,[6] though rifle shooting is normally a Half Blue sport at Cambridge;[13] Oates's biography, on which the former account is based, only says that Heslop was awarded a "Blue".[5]

- ^ Since 1997, the match (now the "Oxford and Cambridge Match"') has been conducted in gallery rifle.[15]

- ^ Naturalists disagree as to whether the pygmy hippopotamus should be considered a member of the genus Hexaprotodon or of Choeropsis, though modern authorities generally favour Choeropsis.[27]

- ^ Oates describes "the 202 meticulously set specimens in [Heslop's] collection", though it is not clear whether this refers exclusively to those of Apatura iris.[8]

- ^ Apatura iris favours oak and willow trees in its habitat; the latter are generally out-completed by conifer trees where both are present, meaning that the butterflies do not flourish in conifer woodland.[44]

- ^ Robinson, Flacke and Hentschel give his children as one son and three daughters.[23] A photograph of his children published by Oates shows a total of three.[42]

References

[edit]- ^ a b Oates 2005, p. 164.

- ^ a b c Oates 2005, p. 171.

- ^ a b De Worms 1970, p. 245.

- ^ a b c d Burton 1971, p. 10.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Oates 2005, p. 165.

- ^ a b c d e f g Robinson, Flacke & Hentschel 2017, p. 58.

- ^ Oates 2021, p. 349.

- ^ a b c d Oates 2021, p. 38.

- ^ Le Vay 2011, p. 51.

- ^ Oates 2005; De Worms 1970, p. 245.

- ^ a b Oates 2005, p. 169.

- ^ a b De Worms 1970, p. 265.

- ^ Lyttelton 1913, p. 212.

- ^ Cambridge University Revolver and Pistol Club 2019.

- ^ National Rifle Association 2021, p. 187.

- ^ a b c d e f Robinson, Flacke & Hentschel 2017, p. 59.

- ^ a b c d e Oates 2005, p. 166.

- ^ a b c Robinson, Flacke & Hentschel 2017, p. 64.

- ^ a b c d e Robinson, Flacke & Hentschel 2017, p. 60.

- ^ a b c d e f Robinson, Flacke & Hentschel 2017, p. 62.

- ^ Quoted in Oates 2005, p. 166.

- ^ Oates 2021, p. 96.

- ^ a b c d Robinson, Flacke & Hentschel 2017, p. 61.

- ^ Robinson, Flacke & Hentschel 2017, pp. 60–61.

- ^ a b c Robinson, Flacke & Hentschel 2017, p. 66.

- ^ Robinson, Flacke & Hentschel 2017, p. 65.

- ^ Gentry 2013, p. 63.

- ^ Robinson, Flacke & Hentschel 2017, pp. 65–66.

- ^ Eltringham 1993.

- ^ Robinson, Flacke & Hentschel 2017, p. 67; Eltringham 1993.

- ^ Robinson, Flacke & Hentschel 2017, fig. 5.8.

- ^ Oates 2005, pp. 168–169.

- ^ Oates 2021, pp. 22–23.

- ^ Oates 2021, p. 39.

- ^ Robinson, Flacke & Hentschel 2017, pp. 59–60.

- ^ Salmon 2000, p. 370.

- ^ Burton 1971, p. 11.

- ^ Oates 2005, p. 170.

- ^ Oates 2005, pp. 170–171.

- ^ Jacobs 1964, p. 28.

- ^ a b De Worms 1970, p. 246.

- ^ a b c d e Oates 2005, p. 167.

- ^ De Worms 1970, p. 246; Oates 2005, p. 167.

- ^ Oates 2021, p. 197.

- ^ Oates 2021, pp. 197, 327.

- ^ Oates 2021, p. 43.

- ^ BBC 2023.

- ^ Oates 2005, pp. 165, 171.

Sources

[edit]- BBC (2023). "Country Parliament". Programme Index. Archived from the original on 16 May 2023. Retrieved 16 May 2023.

- Burton, John F. (1971). "I. R. P. Heslop" (PDF). Proceedings of the Bristol Naturalists' Society. 32: 10–11. ISSN 0068-1040. Retrieved 1 April 2023.

- Cambridge University Revolver and Pistol Club (2019). "Rifle Varsity". Cambridge University Revolver and Pistol Club. Archived from the original on 25 March 2023. Retrieved 26 March 2023.

- De Worms, Charles George Maurice (1970). "Obituary: Ian Robert Penicuick Heslop (1904–1970)" (PDF). The Entomologist's Record and Journal of Variation. 82: 245–246. ISSN 0013-8916. Retrieved 1 April 2023.

- Eltringham, S. Keith (1993). "Pigs, Peccaries and Hippos Status Survey and Action Plan". World Conservation Union Status Survey. Archived from the original on 5 January 2008. Retrieved 23 August 2008.

- Gentry, Alan (2013). "Family Hippopotamidae". In Kingdon, Jonathan; Hoffmann, Michael (eds.). Mammals of Africa. Vol. 6. London: Bloomsbury. pp. 63–64. ISBN 9781408122563.

- Jacobs, S. N. A. (1964). "Notes and Views of the Purple Emperor". The Entomologist's Record and Journal of Variation. 76: 28. ISSN 0013-8916. Archived from the original on 25 November 2021. Retrieved 31 May 2023.

- Le Vay, Benedict (2011) [2006]. Ben Le Vay's Eccentric Cambridge. Chalfont St. Peter: Bradt Travel Guides. ISBN 9781841624273.

- Lyttelton, Robert Henry (1913). Fifty Years of Sport at Oxford, Cambridge and the Great Public Schools. London: W. Southwood.

- Oates, Matthew (2005). "Extreme Butterfly Collecting: A Biography of I. R. P. Heslop". British Wildlife. 34 (4): 164–171. ISSN 0958-0956.

- Oates, Matthew (2021) [2020]. His Imperial Majesty: A Natural History of the Purple Emperor. London: Bloomsbury. ISBN 9781472950161.

- National Rifle Association (2021). The NRA Handbook (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 24 March 2023. Retrieved 24 March 2023.

- Robinson, Phillip T.; Flacke, Gabriella L.; Hentschel, Knut M. (2017). The Pygmy Hippo Story: West Africa's Enigma of the Rainforest. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780190611859.

- Salmon, Michael A. (2000). The Aurelian Legacy: A History of British Butterflies and Their Collectors. Leiden: Brill. ISBN 9780946589401.