Ian Carmichael

Ian Carmichael | |

|---|---|

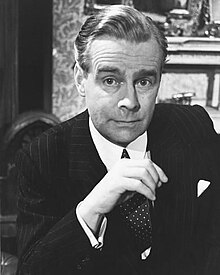

Carmichael in 1972 as Lord Peter Wimsey | |

| Born | Ian Gillett Carmichael 18 June 1920 Kingston upon Hull, East Riding of Yorkshire, England |

| Died | 5 February 2010 (aged 89) Grosmont, North Yorkshire, England |

| Occupation | Actor |

| Spouses | |

| Children | 2 |

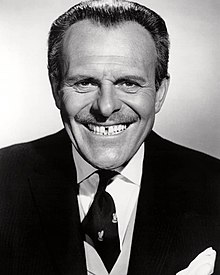

Ian Gillett Carmichael, OBE (18 June 1920 – 5 February 2010) was an English actor who worked prolifically on stage, screen and radio in a career that spanned seventy years. Born in Kingston upon Hull, in the East Riding of Yorkshire, he trained at the Royal Academy of Dramatic Art, but his studies—and the early stages of his career—were curtailed by the Second World War. After his demobilisation he returned to acting and found success, initially in revue and sketch productions.

In 1955 Carmichael was noticed by the film producers John and Roy Boulting, who cast him in five of their films as one of the major players. The first was the 1956 film Private's Progress, a satire on the British Army; he received critical and popular praise for the role, including from the American market. In many of his roles he played a likeable, often accident-prone, innocent. In the mid-1960s he played Bertie Wooster in adaptations of the works of P. G. Wodehouse in The World of Wooster for BBC Television, for which he received mostly positive reviews, including from Wodehouse. In the early 1970s he played another upper-class literary character, Lord Peter Wimsey, the amateur but talented investigator created by Dorothy L. Sayers.

Much of Carmichael's success came through a disciplined approach to training and rehearsing for a role. He learned much about the craft and technique of humour while appearing with the comic actor Leo Franklyn. Although Carmichael tired of being typecast as the affable but bumbling upper-class Englishman, his craft ensured that while audiences laughed at his antics, he retained their affection; Dennis Barker, in Carmichael's obituary in The Guardian, wrote that he "could play fool parts in a way that did not cut the characters completely off from human sympathy: a certain dignity was always maintained".[1]

Biography

Early life

Ian Gillett Carmichael was born on 18 June 1920 in Kingston upon Hull, in the East Riding of Yorkshire. He was the eldest child of Kate (née Gillett) and her husband Arthur Denholm Carmichael, an optician on the premises of his family's firm of jewellers.[2][3] Carmichael had two younger sisters, the twins Mary and Margaret, who were born in December 1923.[4] Robert Fairclough, his biographer, describes Carmichael's upbringing as a "privileged, pampered existence"; his parents employed maids and a cook.[5] His infant education included one term at the local Froebel House School when he was four, but this was curtailed after his parents were shocked at the "alarmingly foul language he began bringing home", according to Alex Jennings, Carmichael's biographer in the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography.[3][6]

In 1928 Carmichael was sent to Scarborough College, a prep school in North Yorkshire, which he attended between the ages of seven and thirteen.[7] He did not like the spartan and authoritarian regime at the school. He described the discipline as "Dickensian", with corporal punishment used for even minor infringements of the rules; ablutions in the morning and evening were conducted with cold water—which often had a film of ice on the top during winter.[8]

In 1933 Carmichael left Scarborough College and entered Bromsgrove School, a public school in Worcestershire.[3][a] He soon concluded that "the new curriculum was not arduous",[10] which gave him the opportunity for focus on matters that were of more interest for him: acting, popular music and cricket.[3][11] In the late 1930s Carmichael decided to go to the Royal Academy of Dramatic Art (RADA) in London. His parents would have preferred he went into the family jewellery business, but accepted their son's decision and supported him financially when he left Yorkshire for London in January 1939.[12][13]

Early career and war service, 1939–1946

Carmichael enjoyed his time at RADA, including the fact that women outnumbered men on his course, which he described as "heady stuff" after his boys-only boarding school.[14] He remembered the time at RADA in the late 1930s fondly in his autobiography, describing it as:

A period of unconfined joy, occasioned by my finally shaking off the shackles of school discipline and being able to mix daily with young men and young women who shared my interests and enthusiasms. This joy was, nevertheless, being tempered by the worsening European situation. The fear that now, just as I was standing on the threshold of a future that I had dreamed about for years, the whole thing might be snuffed out like a candle was too unbearable to contemplate.[15]

During his second term Carmichael had his first professional acting role: as a robot in Karel Čapek's R.U.R. at the People's Palace theatre, in Mile End, East London.[16] He recalled the experience as "a dull play performed in a cold and uninspiring theatre and my particular contribution required absolutely no acting talent whatsoever".[17] He then appeared as Flute in A Midsummer Night's Dream at RADA's Vanbrugh Theatre. The opening night was 1 September 1939, the day Hitler invaded Poland. After the play's second performance its run was ended, as RADA shut down in anticipation that war was about to be declared; the following day the UK joined the war. Carmichael returned to his familial home and completed the forms to join the Officer Cadet Reserve, hoping to be commissioned as an officer. He helped gather the harvest in a nearby farm until 2 October, when he was attested into the army; he was told he would have to wait until he was twenty—on 18 June 1940—before he started training.[18]

As the early months of the war were marked by limited military action, RADA reassessed its closure, and decided to reopen. Carmichael returned to London and shared lodgings with two fellow RADA students, Geoffrey Hibbert and Patrick Macnee; Carmichael and Macnee became lifelong friends. Between June and August 1940 Carmichael was on a ten-week tour of Nine Sharp, a revue developed by Herbert Farjeon. After the tour Carmichael reported for training on 12 September at Catterick Garrison.[19] After ten weeks' basic training, he was posted to the Royal Military Academy Sandhurst to become an officer cadet.[20] He completed his training and passed out in March 1941 as a second lieutenant in the 22nd Dragoons, part of the Royal Armoured Corps.[21][22]

At the end of training manoeuvres in November 1941, near Whitby, North Yorkshire, Carmichael was struggling to close the hatch of his Valentine tank when it slammed down, cutting off the top of a finger on his left hand. The surgery was botched and caused him pain for several months; he had a second operation several months later.[23] He described it as "dashed unfortunate"[24] and "my one and only war-wound, albeit a self-inflicted one".[23]

In between training for the liberation of France Carmichael began producing revues and productions as part of his brigade's entertainment. On 16 June 1944, ten days after D-Day, Carmichael and his armoured reconnaissance troop landed in France. He fought through to Germany with the regiment and by the time of Victory in Europe Day in May 1945, he had been promoted to captain and mentioned in despatches.[25][26]

Carmichael's regiment was part of 30 Corps and an initial post-war challenge in Germany was the welfare of the occupying forces. The corps' commanding officer was Lieutenant-General Brian Horrocks, who ordered a repertory company to be formed for entertainment. When Carmichael auditioned he recognised the major in charge of the unit as Richard Stone, an actor who had been a contemporary at RADA; Carmichael was taken into the company and assisted Stone with auditioning other members.[28][27] One of the comedians who auditioned was Frankie Howerd, whom Carmichael thought "very gauche ... too undisciplined and not very funny either. Very much the amateur".[29] Stone disagreed and signed the comic up to perform in a Royal Army Service Corps concert party.[30] The corps' company was also joined by actors from Entertainments National Service Association (ENSA); Carmichael did not often appear on stage with them, but worked as the producer of twenty shows. In April 1946 Stone was promoted and was transferred to the UK; Carmichael was promoted to major and took control of the theatrical company. His leadership of the company was short-lived, as he was demobilised that July.[31][24]

Early post-war career, 1946–1955

In July 1946 Carmichael signed with Stone, who had also been demobilised and had set up as a theatrical agent. Carmichael obtained his first post-war role in the revue Between Ourselves in mid-1946 before he appeared in two small roles in the comedy She Wanted a Cream Front Door— a hotel receptionist and a BBC reporter. The production went on a twelve-week tour round Britain from October 1946, and then ran at the Apollo Theatre in Shaftesbury Avenue, London, for four months.[32]

Between 1947 and 1951 Carmichael appeared on stage in both plays and revues —the latter often at the Players' Theatre in Villiers Street, Charing Cross. He made his debut appearance on BBC television in 1947 in New Faces, a revue that also included Zoe Gail, Bill Fraser and Charles Hawtrey.[33] From 1948 he also began appearing in films, including Bond Street (1948), Trottie True and Dear Mr. Prohack (both 1949); these early roles were minor parts and he was uncredited.[34] He spent much of 1949 in a thirty-week tour of Britain with the operetta The Lilac Domino.[35] According to Jennings, Carmichael's "first conspicuous success" was The Lyric Revue in 1951; the production transferred to The Globe (now the Gielgud Theatre) as The Globe Revue in 1952.[3] He received a positive review in the industry publication The Stage, which reported that he "hits the bull's-eye" for his comic performance in one sketch, "Bank Holiday", which involved him undressing on the beach under a mackintosh.[36]

Carmichael spent the next three years appearing in stage revues and small roles in films.[3] Although he enjoyed working in revues, he was concerned about being stuck in a career rut. In a 1954 interview in The Stage, he said "I'm afraid that managers and directors may think of me only as a revue artist, and much as I enjoy acting in sketches I feel there must be a limit to the number of characters one is able to create. What I would like now is to be offered a part in light comedy or a farce".[37] Between November 1954 and May 1955 he appeared as David Prentice in the stage production of Simon and Laura alongside Roland Culver and Coral Browne at the Strand Theatre, London. The following year a film version was directed by Muriel Box; she asked Carmichael to repeat his role, while Browne and Culver's roles were taken by Kay Kendall and Peter Finch.[3] The reviewer for The Times thought Carmichael "comes near to stealing the film from both of them".[38] In 1955 Carmichael also appeared in The Colditz Story. He played Robin Cartwright, an officer in the Guards, and spent much of his screen time appearing with Richard Wattis; the two men provided an element of comic relief in the film, with what Fairclough describes as a "Flanagan and Allen tribute act".[39] The Colditz Story was Carmichael's ninth film role and he had, Fairclough notes, risen to sixth in the credits behind John Mills and Eric Portman.[40]

Screen success, 1955–1962

In 1955 Carmichael was contacted by the filmmaker twins the Boulting brothers. They wanted him to appear in two film versions of novels—Private's Progress by Alan Hackney and Brothers in Law by Henry Cecil—with an option for five films in all;[41][42] the final contract was for a total of six films.[43] The Boultings' first work with Carmichael was the 1956 film Private's Progress, a satire on the British Army.[44][b] The film opened in February 1956 and starred Carmichael, Richard Attenborough, Dennis Price and Terry-Thomas.[47] The film historian Alan Boulton observed "Reviews were decidedly mixed and the critical response did not match the popular enthusiasm for the film";[43] it was either the second or third most popular film at the British box office that year.[48][49] Carmichael received praise for his role, however, including from The Manchester Guardian, which thought he "fulfils his promise as a comedian";[50] the reviewer for The Times thought Carmichael acted "with an unfailing tact and sympathy—he even manages to make a drunken scene seem rich in comedy".[51] The film introduced American audiences to Carmichael, and his screen presence in the US was warmly received by reviewers. The reviewer Margaret Hinxman, writing in Picturegoer, considered that after Private's Progress Carmichael had become "one of Britain's choicest screen exports".[52]

From June to September 1956 Carmichael was involved in the filming of Brothers in Law, which was directed by Roy Boulting; others in the cast included Attenborough and Terry-Thomas.[53] When the film was released in March 1957 Carmichael received positive reviews,[54] including from Philip Oakes, the reviewer from The Evening Standard, who concluded that Carmichael "confirms his placing in my form book as our best light comedian".[55] The reviewer for The Manchester Guardian thought Carmichael was "irrepressibly funny in his well-bred, well-intentioned, bewildered ineptitude".[56]

In September 1957 Carmichael appeared in a third Boulting brothers film, Lucky Jim in which he appeared alongside Terry-Thomas and Hugh Griffith in an adaptation of a 1954 novel by Kingsley Amis.[57] Fairclough notes that while the film was not well received by the critics, Carmichael's performance received great praise.[58] The Manchester Guardian considered that Carmichael, "although in many ways excellent, has fewer chances than in Brothers-in-Law to delight us with those studies in agonised embarrassment in which he excels",[59] while The Daily Telegraph reviewer considered "[Carmichael's] Jim, complete with North-Country accent and the ability to pull comic faces, might so easily have been the author's creation brought to life off the page."[60]

Carmichael then appeared in a fourth film with the Boultings, Happy Is the Bride, a lightweight comedy of manners released in March 1958 which also included Janette Scott, Cecil Parker, Terry-Thomas and Joyce Grenfell.[61] Carmichael spent much of the end of 1957 and most of 1958 on stage with The Tunnel of Love. The journalist R. B. Marriott described it as a "slightly crazy, wonderfully ridiculous comedy",[62] and it had a five-week tour around the UK which preceded a run at Her Majesty's Theatre, London, between December 1957 and August 1958.[63] During the run, in April 1958, Carmichael was interviewed for Desert Island Discs by Roy Plomley on the BBC Home Service.[64][c]

Carmichael once again appeared as Stanley Windrush, the character he portrayed in Private's Progress, in his fifth film with the Boultings, I'm All Right Jack, which was released in August 1959. Several other actors from Private's Progress also reprised their roles: Price (as Bertram Tracepurcel); Attenborough (as Sidney De Vere Cox) and Terry-Thomas (as Major Hitchcock). A new character was introduced in the film, Peter Sellers as the trade union shop steward Fred Kite.[66][67] The film was the highest-grossing at the British box office in 1960 and earned Sellers the award for Best British Actor at the 13th British Academy Film Awards.[68][69] Although Sellers received most of the plaudits for the film, Carmichael was given good reviews for his role, with The Illustrated London News saying he was "in excellent fooling" and "delicious both at work and at play".[70][71] In 1960 Carmichael appeared in School for Scoundrels, based on Stephen Potter's "gamesmanship" series of books.[72][d] Appearing alongside him were Terry-Thomas, Alastair Sim and Janette Scott. The reviews for the film were not positive, but the actors were praised for their work in it.[73]

The release of School for Scoundrels was Carmichael's tenth film in five years. Fairclough observes that during the late 1950s and early 1960s, Carmichael began to get a reputation among his colleagues as being difficult to work with. Eric Maschwitz, the BBC's Head of Light Entertainment for Television, recorded in an internal memo that Carmichael had given "great difficulty" during negotiations, and concluded that "his head seems to have been a little turned by his success".[74] Some actors had to point out to him that he was "doing a Carmichael" whenever he tried to improve his billing, or upstage his fellow actors, including Derek Nimmo in 1962, during the filming of The Amorous Prawn.[75] Despite the criticism, Carmichael described the period as "I think the happiest five or six years of my whole career".[76]

In December 1961 Carmichael was appearing in the comedy mystery play The Gazebo every evening and filming Double Bunk during the day. The mental and physical toll on him was too much, and he collapsed in the middle of a performance. The show's producer, Harold Fielding, instructed Carmichael to take at least two week's holiday to rest, and he paid for Carmichael and his wife to have a holiday in Switzerland. He returned to the show on 23 December, but he lost his voice during the Boxing Day show and could only complete Act 1. He returned to the show after a few days, but left permanently on 28 January 1962 on his doctor's orders.[42][77]

Wooster and Wimsey, 1962–1979

Tastes in film changed in the late 1950s and early 1960s, with the new wave of British films moving away from plots centred on the upper classes and the establishment, to works such as Look Back in Anger, Room at the Top (both 1959), Saturday Night and Sunday Morning (1960) and The Loneliness of the Long Distance Runner (1962), where working class drama came to the fore.[78][79] One of the effects of the new movement was a downturn in the number of films that wanted a character like those normally played by Carmichael.[3][80] He was still being offered some film roles, but all, he said, "were variations on the same old bumbling, accident-prone clot" with which he was becoming increasingly bored.[81]

In August 1964 the BBC approached Carmichael to discuss the possibility of his taking the role of Bertie Wooster—described by Fairclough as "the misadventuring, 1920s upper-class loafer"—for adaptations of the works of P. G. Wodehouse. He turned it down, as he had agreed to appear on Broadway, taking the lead in a production of the farce Boeing-Boeing.[82] He appeared at the Cort Theatre in February 1965, but the run ended after 23 performances, as the farce was not to the taste of New York audiences. Carmichael was delighted by the early close, as he hated his time in the US and said "I found New York a disturbing, violent city and I disliked it instantly". As soon as he heard the production was to close, he sent a telegram to the BBC to note his availability to play Wooster.[83][84] Carmichael negotiated a fee of 500 guineas (£525) per half-hour episode, and assisted in finding the right person for Jeeves, eventually selecting Dennis Price.[85][e]

The first series of The World of Wooster received the Guild of Television Producers and Directors award for best comedy series production of 1965,[87] and the programme ran for three series, broadcast between May 1965 and November 1967, comprising twenty episodes in total.[88] Reviews for Carmichael were positive,[89] with a reviewer in The Times declaring "The World of Wooster is also a triumph of casting, for Ian Carmichael and Dennis Price are perfect impersonators of two characters who are by no means lay-figures ... They are a priceless pair."[90] A different reviewer pointed out one drawback of the 44-year-old Carmichael's performance: "If we have thought of Bertie Wooster as eternally 22, not far in time from enjoyably wasted university days, Mr. Ian Carmichael opposes our view with a Bertie who is older but hopefully fixed in an inescapable mental youth."[91] The best review, as far as Carmichael and the producer Michael Mills were concerned, was from Wodehouse, who sent a telegram to the BBC:

To the producer and cast of the Jeeves sketches.

Thank you all for the perfectly wonderful performances. I am simply delighted with it. Bertie and Jeeves are just as I have always imagined them, and every part is played just right.

Bless you!

P. G. Wodehouse[89]

Wodehouse later reconsidered his opinion and thought Carmichael overacted in the role.[92] Only one of the episodes remains: the others were wiped to reuse the expensive videotape.[93]

In September 1970 Carmichael was the lead role in Bachelor Father, a sitcom loosely based on the true story of a single man who fostered twelve children. There were two series—one in 1970, one the following year—and a total of 22 episodes; he negotiated a salary of £1,500 per episode, making him the best-paid actor at the BBC.[94][f] The media historian Mark Lewisohn thought that the programme, "although ostensibly a middle-of-the-road family sitcom of no great ambition, came over as a polished and professional piece of work that pleased audiences over two extended series".[95]

Carmichael was one of the driving forces behind the BBC's decision to adapt Dorothy L. Sayers's Lord Peter Wimsey stories for television. He first had the idea of appearing as Wimsey in 1966, but various factors—including financing, Carmichael's association with Bertie Wooster in the public's eye and difficulty obtaining the rights—delayed the project. By January 1971, however, they were able to start filming the first programme, Clouds of Witness, which was broadcast in 1972 in five parts. This was followed by The Unpleasantness at the Bellona Club, Murder Must Advertise, The Nine Tailors and The Five Red Herrings between February 1973 and August 1975.[96][97] Richard Last, writing in The Daily Telegraph thought Carmichael was "an inspired piece of casting. ... he has exactly the right outward touch of aristocratic frivolity but more than the ability to suggest the steel underneath".[98] Clive James, reviewing for The Observer, described Carmichael as "an extremely clever actor", and thought he was "turning in one of those thespian efforts which seem easy at the time but which in retrospect are found to have been the ideal embodiment of the written character".[99] Carmichael went on to play Wimsey on BBC Radio 4, recording nine adaptations with Peter Jones as Mervyn Bunter, Wimsey's valet.[100]

In 1979 Carmichael appeared in The Lady Vanishes, which starred Elliott Gould and Cybill Shepherd; the film was a remake of Alfred Hitchcock's 1938 film of the same name. Carmichael appeared as Caldicott alongside Arthur Lowe's character Charters, two cricket-obsessed English gentlemen; the roles were played in the original by Naunton Wayne and Basil Radford. The journalist Patrick Humphries, while describing the film as "lamentable", thought that only Carmichael and Lowe "emerge with any credibility".[101][102] Carmichael was interviewed on Desert Island Discs for a second time in June 1979.[103][g]

Semi-retirement, 1979–2009

In 1979 Carmichael published his autobiography Will the Real Ian Carmichael ..., which marked what Fairclough calls his "semi-retirement" in Yorkshire.[104] He continued to work periodically, including providing the voice for Rat in the 1983 film The Wind in the Willows[105] and as the narrator for the television series of the same name between 1984 and 1990.[106][107] He revisited the works of Wodehouse in the late 1980s and early 1990s, providing the voice of Galahad Threepwood for two radio productions, Pigs Have Wings and Galahad at Blandings.[108][109]

In 1992 and 1993 he played Sir James Menzies in two series of Strathblair, a BBC family drama set in 1950 broadcast on Sunday evenings.[110] He undertook his last stage role in June 1995, playing Sir Peter Teazle in Richard Brinsley Sheridan's The School for Scandal at the Chichester Festival Theatre.[111] From 2003 he took his final role: that of T. J. Middleditch in the ITV hospital drama series The Royal.[112] He continued filming with The Royal until 2009.[113]

Personal life

In late March 1941, when Carmichael's regiment was posted to Whitby he met "Pym"—Jean Pyman Maclean—who he described as "blonde, just eighteen, five feet six, sensationally pretty and a beautiful dancer"; he thought her personality was "warm ... genuine. There was an innocence about her, an unsophistication that disarmed even the most worldly".[114] The couple became engaged in May 1942 and married on 6 October 1943;[115] they had two daughters, Lee (born in 1946) and Sally (born in 1949).[3] Pym died of cancer in 1983.[116]

In 1984 Carmichael recorded a series of short stories for the BBC; the programmes were produced by Kate Fenton. They began a relationship and she left the BBC in 1985 and moved in with him in the Esk Valley, near Whitby. They were married in July 1992.[3][117][118] Carmichael enjoyed playing and watching cricket, and listed it as one of this interests in Who's Who.[119] He was a member of the Lord's Taverners cricket charity from 1956 until October 1976,[120] and would relax on film sets playing a casual game with other members of the cast and crew, a practice he was introduced to by the Boulting brothers.[121] He was also a member of the Marylebone Cricket Club.[122]

In 2003 Carmichael was appointed OBE for services to drama.[123] He died on 5 February 2010 of a pulmonary embolism.[3]

Screen persona and technique

Carmichael learned much of his technique from the thirty-week tour of The Lilac Domino he undertook in the late 1940s, where he appeared opposite the comic actor Leo Franklyn.[122][124] Carmichael acknowledged the credit for his development as a light comic actor went "in its entirety to the training, coaxing and encouragement of ... Franklyn",[124] who "showed me how to time my laughs and how to play an audience".[35] Carmichael's experience in revue helped when he worked in a dramatic play; his experience in getting a character across to an audience quickly in a short sketch showed him that "it is very important to establish a comedy character as soon as possible. Your whole performance may depend on this being done".[62]

Carmichael polished his performances through extensive rehearsals and training.[125] The screenwriter Paul Dehn acknowledges the effort and discipline needed by Carmichael to achieve a polished feel to his act, describing how Carmichael would "slave for hours to perfect one stumble on a stairway and, having got it, ... [would] make it seem effortless thereafter".[126] Jennings considers much of Carmichael's seemingly effortless light touch "was built on a hugely disciplined and virtuosic technique".[3] Carmichael's choice of comedy was character-, rather than situation-based and when the film or play generated its atmosphere from normal, recognisable aspects of life.[62] He selected his work projects carefully and became involved in the development and production side as closely as possible, or initiated the project himself.[95]

The image he portrayed in many of his works was summarised by one obituarist as "the affable, archetypal silly ass Englishman" with a "wide-eyed boyish grin, bemused courtesy and hapless, trusting manner".[122] He became somewhat typecast with the character, but audiences liked him in the role, and "he polished this persona with great care", according to his obituarist in The Daily Telegraph, even though he tired of playing the role so often.[127][122] One of the attractions for the public was that he played his parts to get the audience's sympathy for the character, but with a measure of dignity that viewers could relate to.[24][1] During Carmichael's semi-retirement, the Boulting brothers told him that they had not shown the range of his talents, and that "perhaps they should not virtually have confined him to the playing of twerps".[1] When he took the role of Wimsey—the intelligent, cultured and effective investigator—the critic Nancy Banks-Smith wrote that "it was high time that Ian Carmichael was given the opportunity to look intelligent".[128]

Notes and references

Notes

- ^ A public school in the UK is a fee-paying institution, associated with the ruling class and upper echelons of banking, business and industry.[9]

- ^ Over the course of the late 1950s and early 1960s the Boultings made films that took "sharp, but generally good-tempered swipes at such social bastions" in Britain. These included Private's Progress (1956; the army), Brothers in Law (1957; the legal profession), Lucky Jim (1957; academia), I'm All Right Jack (1959; trade unions and management), Carlton-Browne of the F.O. (1959; the Foreign Office) and Heavens Above! (1963; the Church of England).[44][45] Carmichael appeared in all but Carlton Browne.[46]

- ^ His selection was Gene Kelly, "Les Girls"; Bing Crosby, "Prisoner of Love"; Fred Astaire, "Let's Kiss and Make Up"; The London Palladium Orchestra, playing a selection from Lilac Domino; Glenn Miller Orchestra, "Moonlight Serenade"; Kay Thompson, "How Deep Is the Ocean?"; Waltz from Act one of Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky's Swan Lake; Philharmonia Orchestra, with Herbert von Karajan conducting; Frank Sinatra, "I've Got the World on a String". His luxury items were writing materials and beer.[65]

- ^ The books are Gamesmanship (1947), Lifemanship (1950), Oneupmanship (1952) and Supermanship (1958).[72]

- ^ According to calculations based on the Consumer Price Index measure of inflation, 500 guineas in 1965 is approximately £12,840 in 2023, according to calculations based on Consumer Price Index measure of inflation.[86]

- ^ According to calculations based on the Consumer Price Index measure of inflation, £1,500 in 1970 is approximately £29,310 in 2023, according to calculations based on Consumer Price Index measure of inflation.[86]

- ^ His selection was Gustav Holst, The Planets; Orchestra of the Royal Opera House, the theme from Murder on the Orient Express; Aram Khachaturian, Adagio of Spartacus and Phrygia from Spartacus; Jimmy Dorsey and his orchestra, "On the Alamo"; Neal Hefti, the theme from the film Boeing, Boeing; Nino Castelnuovo and Ellen Farner, the duet of Guy and Madeleine from The Umbrellas of Cherbourg; and Count Basie and His Orchestra, Doin' Basie's Thing. His book choice was Leo Tolstoy's War and Peace and his luxury item was paper and pencils.[103]

References

- ^ a b c Barker 2010, p. 35.

- ^ Hubbard, O'Donnell & Steen 1989, p. 63.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Jennings 2014.

- ^ Fairclough 2011, p. 11.

- ^ Fairclough 2011, pp. 5, 11.

- ^ Carmichael 1979, p. 29.

- ^ Fairclough 2011, pp. 13–15.

- ^ Carmichael 1979, pp. 32–33.

- ^ Sampson 1982, p. 124.

- ^ Carmichael 1979, p. 48.

- ^ Carmichael 1979, pp. 48, 55–59.

- ^ Fairclough 2011, pp. 22–23.

- ^ Carmichael 1979, p. 69.

- ^ Carmichael 1979, pp. 74–75.

- ^ Carmichael 1979, p. 72.

- ^ Fairclough 2011, p. 27.

- ^ Carmichael 1979, pp. 77–78.

- ^ Fairclough 2011, pp. 27–28.

- ^ Fairclough 2011, pp. 29–31.

- ^ Carmichael 1979, p. 108.

- ^ Fairclough 2011, p. 33.

- ^ The London Gazette. 28 March 1941.

- ^ a b Carmichael 1979, pp. 127–129.

- ^ a b c "Ian Carmichael: Actor". The Times. 8 February 2010.

- ^ Carmichael 1979, pp. 145–146, 160–179; Fairclough 2011, pp. 36–40; Barker 2010, p. 35.

- ^ The London Gazette. 7 August 1945.

- ^ a b Fairclough 2011, p. 41.

- ^ Carmichael 1979, pp. 182–184.

- ^ Carmichael 1979, p. 184.

- ^ Fairclough 2011, p. 42.

- ^ Carmichael 1979, pp. 190–191.

- ^ Carmichael 1979, pp. 197–199; Fairclough 2011, pp. 44–45; Herbert 1972, p. 609.

- ^ "New Faces". Radio Times.

- ^ Pettigrew 1982, p. 30.

- ^ a b Quinlan 1992, p. 52.

- ^ "The Globe". The Stage.

- ^ Bullock 1954, p. 10.

- ^ "Television's Ideal Married Couple Date". The Times.

- ^ Fairclough 2011, pp. 70–71.

- ^ Fairclough 2011, p. 71.

- ^ Fairclough 2011, p. 77.

- ^ a b Carmichael 1979, pp. 279–280.

- ^ a b Burton 2012, p. 81.

- ^ a b McFarlane 2014.

- ^ Harper & Porter 2003, p. 108.

- ^ "Filmography: Carmichael, Ian". British Film Institute.

- ^ Fairclough 2011, p. 79.

- ^ British Films Made Most Money: Box-Office Survey. The Manchester Guardian.

- ^ Harper & Porter 2003, p. 249.

- ^ "New Films in London". The Manchester Guardian.

- ^ "The Army as a Film Joke". The Times.

- ^ Hinxman 1957, p. 12.

- ^ Carmichael 1979, pp. 285–286.

- ^ Fairclough 2011, p. 91.

- ^ Oakes 1957, p. 8.

- ^ "An Outstanding British Comedy". The Manchester Guardian.

- ^ Whitehead 2014b.

- ^ Fairclough 2011, p. 96.

- ^ "'Lucky Jim' as a British Comedy". The Manchester Guardian.

- ^ "Satire Gone in 'Lucky Jim'". The Daily Telegraph.

- ^ Fairclough 2011, p. 98.

- ^ a b c Marriott 1957, p. 8.

- ^ Fairclough 2011, pp. 107–108, 114.

- ^ "Desert Island Discs: Ian Carmichael (1958)". BBC Genome Project.

- ^ "BBC Radio 4 – Desert Island Discs: Ian Carmichael (1958)". BBC.

- ^ Whitehead 2014a.

- ^ Wells 2000, p. 61.

- ^ Sikov 2002, p. 130.

- ^ "Boultings on top form: Satirical 'I'm All Right, Jack!'". The Manchester Guardian.

- ^ Dent 1959, p. 50.

- ^ Fairclough 2011, pp. 129–130.

- ^ a b Brooke 2014a.

- ^ Fairclough 2011, p. 142.

- ^ Fairclough 2011, pp. 102, 142.

- ^ Fairclough 2011, p. 103.

- ^ McFarlane 1997, p. 115.

- ^ Fairclough 2011, pp. 313–316.

- ^ Wickham 2014.

- ^ Harper & Porter 2003, p. 267.

- ^ Fairclough 2011, pp. 170–172.

- ^ Carmichael 1979, p. 323.

- ^ Fairclough 2011, pp. 180, 189, 196.

- ^ Carmichael 1979, pp. 335–337.

- ^ Weber 2010, p. B17.

- ^ Fairclough 2011, pp. 199–200.

- ^ a b Clark 2023.

- ^ "Best Comedy Series in 1965". BAFTA Awards.

- ^ Brooke 2014b.

- ^ a b Fairclough 2011, p. 204.

- ^ "New Lease of Life for the Short Story". The Times.

- ^ "A Jeeves to Fit the Picture". The Times.

- ^ Taves 2006, p. 114.

- ^ Taves 2006, p. 117.

- ^ Fairclough 2011, pp. 214, 220–223.

- ^ a b Lewisohn 1998, p. 53.

- ^ Fairclough 2011, pp. 236, 238–256.

- ^ Carmichael 1979, pp. 379–382.

- ^ Last 1972, p. 12.

- ^ James 1973, p. 34.

- ^ "Search: Wimsey". BBC Genome.

- ^ Humphries 1986, p. 52.

- ^ Maxford 2002, p. 59.

- ^ a b "BBC Radio 4 – Desert Island Discs: Ian Carmichael (1979)". BBC.

- ^ Fairclough 2011, p. 263.

- ^ Fiddick 1983, p. 2.

- ^ "Ghost at Mole End (1984)". British Film Institute.

- ^ "Happy Birthday (1990)". British Film Institute.

- ^ "Pigs Have Wings". BBC Genome Project.

- ^ "Galahad at Blandings". BBC Genome Project.

- ^ Fairclough 2011, p. 277.

- ^ Fairclough 2011, p. 292.

- ^ Fairclough 2011, pp. 300, 305–307.

- ^ Brooks & Woods 2010.

- ^ Carmichael 1979, pp. 118–119.

- ^ Fairclough 2011, p. 36.

- ^ Fairclough 2011, p. 269.

- ^ Fairclough 2011, p. 286.

- ^ "Biography". Kate Fenton.

- ^ Herbert 1972, p. 609.

- ^ Fairclough 2011, pp. 212–214.

- ^ Carmichael 1979, pp. 282, 319, 330.

- ^ a b c d "Ian Carmichael". The Daily Telegraph. 8 February 2010.

- ^ The London Gazette. 14 June 2003.

- ^ a b Fairclough 2011, p. 53.

- ^ Strachan 2010, p. 34.

- ^ Dehn 1957, p. 6.

- ^ Fairclough 2011, p. 176.

- ^ Banks-Smith 1972, p. 10.

Sources

Books

- Burton, Alan (2012). "From Adolescence into Maturity: the Film Comedy of the Boulting Brothers". In Hunter, I. Q.; Porter, Laraine (eds.). British Comedy Cinema. Abingdon, Oxfordshire: Routledge. pp. 77–88. ISBN 978-0-4156-6665-7.

- Carmichael, Ian (1979). Will the Real Ian Carmichael... London: Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-333-25476-9.

- Fairclough, Robert (2011). This Charming Man: The Life of Ian Carmichael. London: Arum Press. ISBN 978-1-8451-3664-2.

- Harper, Sue; Porter, Vincent (2003). British Cinema of the 1950s: The Decline of Deference. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-1981-5934-6.

- Herbert, Ian, ed. (1972). Who's Who in the Theatre (fifteenth ed.). London: Sir Isaac Pitman and Sons. ISBN 978-0-2733-1528-5.

- Hubbard, Linda S.; O'Donnell, Owen; Steen, Sara J., eds. (1989). Contemporary Theatre, Film and Television. Volume 6. Detroit, Michigan: Gale Research. ISSN 0749-064X.

- Humphries, Patrick (1986). The Films of Alfred Hitchcock. New York: Portland House. ISBN 978-0-5176-0470-0.

- Lewisohn, Mark (1998). Radio Times Guide to TV Comedy. London: BBC Worldwide. ISBN 978-0-5633-6977-6.

- Maxford, Howard (2002). The A-Z of Hitchcock. London: B.T. Batsford. ISBN 978-0-7134-8738-1.

- McFarlane, Brian (1997). An Autobiography of British Cinema. London: Methuen. ISBN 978-0-413-70520-4.

- Pettigrew, Terence (1982). British Film Character Actors: Great Names and Memorable Moments. Newton Abbot, Devon: David & Charles. ISBN 978-0-7153-8270-7.

- Quinlan, David (1992). Quinlan's Illustrated Directory of Film Comedy Actors. New York: Henry Holt. ISBN 978-0-8050-2394-7.

- Sampson, Anthony (1982). The Changing Anatomy of Britain. New York: Random House. ISBN 978-0-3945-3143-4.

- Sikov, Ed (2002). Mr Strangelove; A Biography of Peter Sellers. New York: Hyperion. ISBN 978-1-4013-9895-8.

- Taves, Brian (2006). P.G. Wodehouse and Hollywood: Screenwriting, Satires and Adaptations. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Co. ISBN 978-0-7864-2288-3.

- Wells, Paul (2000). "Comments, Custard Pies and Comic Cuts: The Boulting Brothers at Play, 1955–65". In Burton, Alan; O'Sullivan, Tim; Wells, Paul (eds.). The Family Way: the Boulting Brothers and British Film Culture. Trowbridge, Wiltshire: Flicks Books. pp. 48–68. ISBN 978-0-9489-1159-0.

Journals and magazines

- Hinxman, Margaret (2 March 1957). "Britain's Conquering Clown". Picturegoer. pp. 12–13.

- "New Faces". Radio Times. No. 1243. BBC. 8 August 1947. p. 32.

News

- "A Jeeves to Fit the Picture". The Times. 31 May 1965. p. 14.

- "An Outstanding British Comedy". The Manchester Guardian. 2 March 1957. p. 5.

- Banks-Smith, Nancy (6 April 1972). "Clouds of Witness". The Guardian. p. 10.

- Barker, Dennis (8 February 2010). "Obituary: Ian Carmichael: Actor Known for his Roles as the Archetypal Blithering Englishman". The Guardian. p. 35.

- "Boultings on Top Form: Satirical 'I'm All Right, Jack!'". The Manchester Guardian. 15 August 1959. p. 3.

- "British Films Made Most Money: Box-Office Survey". The Manchester Guardian. 28 December 1956. p. 3.

- Bullock, George (18 February 1954). "Going up the Ladder". The Stage. p. 10.

- Brooks, Richard; Woods, Richard (7 February 2010). "Ian Carmichael: The Dapper Lord of Light Comedy". The Sunday Times. Retrieved 14 November 2023. (subscription required)

- Dehn, Paul (1 March 1957). "Papa Gielgud Shows How". News Chronicle. p. 6.

- Dent, Alan (5 September 1959). "Half-Asleep and Wide-Awake". The Illustrated London News. p. 50.

- Fiddick, Peter (24 December 1983). "Bright lights at Toad Hall". The Guardian. p. 2.

- "The Globe". The Stage. 17 July 1952. p. 9.

- "Ian Carmichael: Actor". The Times. 8 February 2010. Retrieved 14 November 2023. (subscription required)

- "Ian Carmichael; Unassuming Star of 1950s Light Comedies who Found Fresh Fame on Television as Wooster and Wimsey". The Daily Telegraph. 8 February 2010. p. 31.

- James, Clive (4 February 1973). "Redeeming Appearances". The Observer. p. 34.

- Last, Richard (6 April 1972). "Sayers Wimsey Thriller Triumphs". The Daily Telegraph. p. 12.

- "'Lucky Jim' as a British Comedy". The Manchester Guardian. 20 August 1957. p. 5.

- Marriott, R. B. (27 December 1957). "Ian Carmichael Only Wants to Play Comedy". The Stage. p. 8.

- "New Films in London". The Manchester Guardian. 18 February 1956. p. 5.

- "New Lease of Life for the Short Story". The Times. 15 January 1966. p. 5.

- Oakes, Philip (28 February 1957). "Laughter in Question". Evening Standard. p. 8.

- "Satire Gone in 'Lucky Jim'". The Daily Telegraph. 19 August 1957. p. 8.

- Strachan, Alan (8 February 2010). "Ian Carmichael; Actor who Played Likeable Toffs in Golden Age of British Comedy". The Independent. p. 34.

- "Television's Ideal Married Couple Date". The Times. 24 November 1955. p. 14.

- "The Army as a Film Joke". The Times. 20 February 1956. p. 7.

- Weber, Bruce (10 February 2010). "Ian Carmichael, 89, Comic British Actor". The New York Times. p. B17.

Websites

- "Best Comedy Series in 1965". BAFTA Awards. British Academy of Film and Television Arts. Retrieved 14 December 2023.

- "Biography". Kate Fenton. Retrieved 16 December 2023.

- Brooke, Michael (2014a). "School for Scoundrels (1959)". BFI Screenonline. British Film Institute. Retrieved 11 December 2023.

- Brooke, Michael (2014b). "World of Wooster, The (1965-67)". BFI Screenonline. British Film Institute. Retrieved 14 December 2023.

- Clark, Gregory (2023). "The Annual RPI and Average Earnings for Britain, 1209 to Present (New Series)". MeasuringWorth. Archived from the original on 1 April 2023. Retrieved 22 February 2023.

- "BBC Radio 4 – Desert Island Discs: Ian Carmichael (1958)". BBC. Retrieved 14 November 2023.

- "BBC Radio 4 – Desert Island Discs: Ian Carmichael (1979)". BBC. Retrieved 14 November 2023.

- "Desert Island Discs: Ian Carmichael". BBC Genome Project. BBC. Retrieved 11 December 2023.

- "Filmography: Carmichael, Ian". British Film Institute. Archived from the original on 4 August 2012. Retrieved 18 December 2023.

- "Galahad at Blandings". BBC Genome Project. BBC. Retrieved 18 December 2023.

- "Ghost at Mole End (1984)". British Film Institute. Archived from the original on 5 October 2015. Retrieved 18 December 2023.

- "Happy Birthday (1990)". British Film Institute. Archived from the original on 4 October 2015. Retrieved 18 December 2023.

- Jennings, Alex (2014). "Carmichael, Ian Gillett (1920–2010)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/102581. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- McFarlane, Brian (2014). "Boulting Brothers". Reference Guide to British and Irish Film Directors. Retrieved 27 November 2023 – via Screenonline.

- "Pigs Have Wings". BBC Genome Project. BBC. Retrieved 18 December 2023.

- "Search: Wimsey". BBC Genome. BBC. Retrieved 16 December 2023.

- Whitehead, Tony (2014a). "I'm All Right Jack (1959)". BFI Screenonline. British Film Institute. Retrieved 10 December 2023.

- Whitehead, Tony (2014b). "Lucky Jim (1957)". BFI Screenonline. British Film Institute. Retrieved 10 December 2023.

- Wickham, Phil (2014). "British New Wave". BFI Screenonline. British Film Institute. Retrieved 13 December 2023.

London Gazette

- "OBE". The London Gazette (Supplement). No. 56963. 14 June 2003. p. 10.

- "Regular Army. Emergency Commissions (Cadets)". The London Gazette. No. 35121. 28 March 1941. p. 1885.

- "War Office, 9th August 1945". The London Gazette (Supplement). No. 37213. 7 August 1945. p. 4045.

External links

- Ian Carmichael at IMDb

- Ian Carmichael discography at Discogs

- BBC Humber feature on Ian Carmichael

- 1920 births

- 2010 deaths

- Military personnel from Kingston upon Hull

- British Army personnel of World War II

- English male film actors

- English male radio actors

- English male stage actors

- English male television actors

- Officers of the Order of the British Empire

- People educated at Bromsgrove School

- Male actors from Kingston upon Hull

- Royal Armoured Corps officers

- Graduates of the Royal Military College, Sandhurst

- Alumni of the Royal Academy of Dramatic Art

- People educated at Scarborough College

- 22nd Dragoons officers