Saturday Night and Sunday Morning (film)

| Saturday Night and Sunday Morning | |

|---|---|

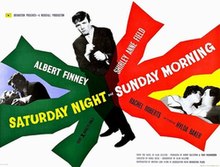

Original British quad format cinema poster | |

| Directed by | Karel Reisz |

| Screenplay by | Alan Sillitoe |

| Based on | Saturday Night and Sunday Morning by Alan Sillitoe |

| Produced by | Tony Richardson Harry Saltzman (executive) |

| Starring | Albert Finney Shirley Anne Field Rachel Roberts Hylda Baker Norman Rossington |

| Cinematography | Freddie Francis |

| Edited by | Seth Holt |

| Music by | John Dankworth |

Production company | |

| Distributed by | Bryanston Films (UK) Continental Distributing (USA) |

Release dates |

|

Running time | 89 minutes |

| Countries | United Kingdom United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | £116,848[2][3] or £120,420[4] |

| Box office | £401,825 (UK) (as of 31 Dec 1964)[5][6] |

Saturday Night and Sunday Morning is a 1960 British kitchen sink drama film directed by Karel Reisz and produced by Tony Richardson.[7] It is an adaptation of the 1958 novel by Alan Sillitoe, with Sillitoe himself writing the screenplay. The plot concerns a young teddy boy machinist, Arthur, who spends his weekends drinking and partying, all the while having an affair with a married woman.

The film is one of a series of "kitchen sink drama" films made in the late 1950s and early 1960s, as part of the British New Wave of filmmaking, from directors such as Reisz, Jack Clayton, Lindsay Anderson, John Schlesinger, and Tony Richardson, and adapted from the works of writers such as Sillitoe, John Braine, and John Osborne. A common trope in these films is the working-class "angry young man" character (in this case, the character of Arthur), who rebels against the oppressive social and economic systems established by previous generations.

In 1999, the British Film Institute named Saturday Night and Sunday Morning the 14th greatest British film of all time on its list of the Top 100 British films.

Plot

[edit]Arthur Seaton is a young machinist at the Raleigh bicycle factory in Nottingham. He is determined not to be tied down to living a life of domestic drudgery like the people around him, including his parents, whom he describes as "dead from the neck up". He spends his wages at weekends on drinking and having a good time.

Arthur is having an affair with Brenda, the wife of Jack, who works at the same factory as Arthur. He also begins a more traditional relationship with Doreen, a beautiful single woman closer to his age. Doreen, who lives with her mother and aspires to be married, avoids Arthur's sexual advances, so he continues to see Brenda, as a sexual outlet.

Brenda becomes pregnant by Arthur, who offers to help raise the child or terminate the unwanted pregnancy (abortion was not legal in Britain at the time the film takes place). Seeking advice, he takes her to see his Aunt Ada, who has Brenda sit in a hot bath and drink gin, which does not work. Brenda asks Arthur for £40 to get an abortion from a doctor.

After Doreen complains about not going anywhere public with Arthur, he takes her to the fair, where he sees Brenda with her family. When he manages to get Brenda alone, she reveals that she has decided to have the child, and then leaves Arthur to go back to her family before she is missed. Arthur follows her on to an amusement ride and gets in a car with her. Brenda's brother-in-law and his friend—both of whom are soldiers—notice her enter the ride and, following, catch Arthur riding with his arm around Brenda. Arthur escapes the ride, but the soldiers catch him later and beat him up in a vacant lot.

Arthur spends a week recovering from his injuries. Doreen visits him, and he makes the moves on her, but is interrupted by his cousin, Bert; they finally consummate their relationship later, at her house, after her mother goes to sleep. Back at work, Arthur runs into Jack, who tells him to stay away from Brenda, as they are staying together. Although he still has mixed feelings about settling into domestic life, Arthur decides to marry Doreen, and, on a hill overlooking a new housing development, they discuss their differing ideas of what their life together will look like.[8]

Cast

[edit]- Albert Finney as Arthur Seaton

- Shirley Anne Field as Doreen

- Rachel Roberts as Brenda

- Hylda Baker as Aunt Ada

- Norman Rossington as Bert

- Bryan Pringle as Jack

- Robert Cawdron as Robboe

- Edna Morris as Mrs Bull

- Elsie Wagstaff as Mrs Seaton

- Frank Pettitt as Mr Seaton

- Avis Bunnage as Blousy Woman

- Colin Blakely as Loudmouth

- Irene Richmond as Doreen's Mother

- Louise Dunn as Betty

- Anne Blake as Civil Defence Officer

- Frank Smith as Himself

- Peter Madden as Drunken Man

- Cameron Hall as Mr Bull

- Alister Williamson as Police Constable

- Peter Sallis as Man in Suit (uncredited)

- Jack Smethurst as Waiter (uncredited)

Production

[edit]Style

[edit]Saturday Night and Sunday Morning was at the forefront of the British New Wave, with its serious portrayal of British working class life and realistic handling of topics such as sex and abortion. It was among the first of the "kitchen sink dramas" that followed the success of the 1956 play Look Back in Anger. Producer Tony Richardson later directed another such film, The Loneliness of the Long Distance Runner (1962), which was also adapted from an Alan Sillitoe book of the same name.

The film received an X rating from the BBFC upon its theatrical release. It was re-rated PG before a 1990 home video release.[9]

Filming locations

[edit]Much of the exterior location filming took place in Nottingham, but some scenes were shot elsewhere. For example, the night scene with a pub named The British Flag in the background was filmed along Culvert Road in Battersea, London, the pub being at the junction of Culvert Road and Sheepcote Lane (now Rowditch Lane).

According to an article that appeared in the Nottingham Evening News on 30 March 1960, the closing scene showing Arthur and Doreen on a grassy slope overlooking a housing development that is still under construction was shot in Wembley with the assistance of Nottingham builders Simms Sons & Cooke.[citation needed]

Financing

[edit]Bryanston guaranteed £81,820 of the budget, the NFFC provided £28,000, Twickenham Studios provided £610, and Richardson deferred his producers fee of £965. The film went £3,500 over budget and two days over schedule when filming at a Nottingham factory proved more difficult than expected.[10] Woodfall bought the rights to the novel from Joseph Janni for £2,000, and got Stiltoe to do the script because they could not afford a professional screenwriter.[11]

Reception

[edit]Saturday Night and Sunday Morning opened at the Warner cinema in London's West End on 27 October 1960, and received generally favourable reviews. It entered general release on the ABC cinema circuit from late January 1961, and was a box-office success, being the third most popular film in Britain that year. It earned a profit of over £500,000,[12] with Bryanston earning a profit of £145,000.[13]

After viewing the film, Ian Fleming sold the rights to the James Bond series to executive producer Harry Saltzman, who, with Albert R. "Cubby" Broccoli, would co-produce every James Bond film between Dr. No (1962) and The Man with the Golden Gun (1974).[14]

Awards

[edit]| Award | Category | Recipient(s) | Result |

|---|---|---|---|

| British Academy Film Awards | Best Film | Karel Reisz | Nominated |

| Best British Film | Won | ||

| Best British Actor | Albert Finney | Nominated | |

| Best British Actress | Rachel Roberts | Won | |

| Best British Screenplay | Alan Sillitoe | Nominated | |

| Most Promising Newcomer to Leading Film Roles | Albert Finney | Won | |

| Mar del Plata International Film Festival | Grand Award for Best Feature Film[15] | Karel Reisz | Won |

| Best Actor | Albert Finney | Won | |

| Best Screenplay | Allan Sillitoe | Won | |

| FIPRESCI Award | Karel Reisz | Won | |

| National Board of Review | Best Actor | Albert Finney | Won |

| Top Foreign Films | Won |

Popular culture references

[edit]In Richard Lester's 1965 comedy Help!, Brenda's famous line "I believe you. Thousands wouldn't." is said by a police inspector after he witnesses The Beatles being attacked by a cult.

The title of indie rock band Arctic Monkeys' 2006 debut album, Whatever People Say I Am, That's What I'm Not, comes from a monologue Arthur delivers in the film.

The Stranglers' live album Saturday Night, Sunday Morning is named after the film. The Counting Crows' 2008 album is titled Saturday Nights & Sunday Mornings.

"Saturday Night Sunday Morning" is the title of a song on Madness' 1999 album Wonderful.

The run-out groove on the B-side of vinyl copies of The Smiths' 1986 album The Queen Is Dead features the line "Them was rotten days," a line said by Aunt Ada in the film. "Why don't you ever take me where's it lively and there's people?", a line said by Doreen before Arthur takes her to the fair, inspired the song "There Is a Light That Never Goes Out" on the same album ("I want to see people and I want to see life"). Morrissey, the lead singer and lyricist of The Smiths, has stated that the film is one of his favourites. The song, "Lily of Laguna", can be heard being sung in the background at the bar; the lyric, "I know she likes me, because she said so," is referenced in the song "Girl Afraid."

Arthur Seaton is mentioned in the song "Where Are They Now?" by The Kinks, which appears on their 1973 album Preservation Act 1.

Arthur Seaton is mentioned in the song "From Across the Kitchen Table" by The Pale Fountains.[citation needed]

The promotional video for the 2013 Franz Ferdinand single "Right Action" uses elements of the graphic design from the film's original cinema poster, and some of the song's lyrics were inspired by a postcard addressed to Karel Reisz that the band's lead singer, Alex Kapranos, found for sale on a market stall.[citation needed]

The film is referenced in Torvill and Dean, a 2018 biopic of Nottingham ice dancers Jayne Torvill and Christopher Dean. Like Arthur, Jayne's father works in the Raleigh factory, and when a young Jayne mentions the film, her mother scolds her and calls the film "rude".

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ The Times, 27 October 1960, pages 2: First advertisement for the film – found through The Times Digital Archive 14 September 2013

- ^ Chapman, J. (2022). The Money Behind the Screen: A History of British Film Finance, 1945-1985. Edinburgh University Press p 360

- ^ Petrie, Duncan James (2017). "Bryanston Films : An Experiment in Cooperative Independent Production and Distribution" (PDF). Historical Journal of Film, Radio and Television: 7. ISSN 1465-3451.

- ^ Chapman, L. (2021). “They wanted a bigger, more ambitious film”: Film Finances and the American “Runaways” That Ran Away. Journal of British Cinema and Television, 18(2), 176–197 p 182. https://doi.org/10.3366/jbctv.2021.0565

- ^ Petrie p. 9

- ^ Sarah Street (2014) Film Finances and the British New Wave, Historical Journal of Film, Radio and Television, 34:1, 23-42 p27, DOI: 10.1080/01439685.2014.879000

- ^ "Saturday Night and Sunday Morning". British Film Institute Collections Search. Retrieved 17 August 2024.

- ^ Russell, Jamie (7 October 2002). "Saturday Night and Sunday Morning (1960)". BBC. Retrieved 9 August 2020.

- ^ Saturday Night and Sunday Morning BBFC page

- ^ Petrie p. 9

- ^ Harper, Sue; Porter, Vincent (2003). British Cinema of The 1950s The Decline of Deference. Oxford University Press USA. p. 184.

- ^ Tino Balio, United Artists: The Company That Changed the Film Industry, University of Wisconsin Press, 1987 p. 239

- ^ Petrie p. 9

- ^ Field, Matthew (2015). Some kind of hero : 007 : the remarkable story of the James Bond films. Ajay Chowdhury. Stroud, Gloucestershire. ISBN 978-0-7509-6421-0. OCLC 930556527.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ "Mar del Plata Awards 1961". Mar del Plata. Retrieved 25 November 2013.

External links

[edit]- Saturday Night and Sunday Morning at the British Film Institute[better source needed]

- Saturday Night and Sunday Morning at the BFI's Screenonline

- Saturday Night and Sunday Morning at IMDb

- Saturday Night and Sunday Morning at AllMovie

- Saturday Night and Sunday Morning at the TCM Movie Database

- Saturday Night and Sunday Morning at Rotten Tomatoes

- British New Wave Essay on Saturday Night and Sunday Morning, at BrokenProjector.com. Archived at Webcite from this original URL 2008-05-08.

- Photographs of The White Horse Public House, Nottingham as featured in the film

- Saturday Night and Sunday Morning on YouTube

- 1960 films

- 1960 directorial debut films

- 1960 drama films

- Films about adultery in the United Kingdom

- Best British Film BAFTA Award winners

- British black-and-white films

- British drama films

- British pregnancy films

- Films based on British novels

- Films shot in London

- Films shot in Nottinghamshire

- Films directed by Karel Reisz

- Films produced by Harry Saltzman

- Films set in Nottingham

- Films about social realism

- Films scored by John Dankworth

- Films about abortion

- 1960s English-language films

- 1960s British films

- English-language drama films