Ian Bremmer

Ian Bremmer | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Bremmer in 2017 | |||||||

| Born | Ian Arthur Bremmer November 12, 1969 Chelsea, Massachusetts, U.S. | ||||||

| Education | Tulane University (BA) Stanford University (MA, PhD) | ||||||

YouTube information | |||||||

| Channel | |||||||

| Years active | 2017–present | ||||||

| Subscribers | 120,000[1] | ||||||

| Total views | 23.4 million[1] | ||||||

| |||||||

| Website | Official website | ||||||

Ian Arthur Bremmer (born November 12, 1969) is an American political scientist, author, and entrepreneur focused on global political risk. He is the founder and president of Eurasia Group, a political risk research and consulting firm. He is also founder of GZERO Media, a digital media firm.

Early life and education

[edit]Bremmer is of Armenian, Syrian (from his maternal grandmother),[2][3] Italian, and German descent, the son of Maria J. (née Scrivano) and Arthur Bremmer.[4] His father served in the Korean War, and died at the age of 46 when Bremmer was four. Bremmer grew up in housing projects in Chelsea, Massachusetts, near Boston.[5] He enrolled in St. Dominic Savio High School in East Boston at age 11.[6][7] At 15, he enrolled in university and went on to earn a BA degree in international relations, magna cum laude, from Tulane University in 1989. Bremmer subsequently obtained an MA degree in 1991 and a PhD in 1994, both in political science from Stanford University. His doctoral dissertation was "The politics of ethnicity: Russians in the Ukraine".[8][9][6]

Career

[edit]Eurasia Group

[edit]Bremmer founded the political risk research and consulting firm Eurasia Group in 1998 in the offices of the World Policy Institute in New York City.[10] The firm opened a London office in 2000; a Washington, DC office (2005); a Tokyo office (2015); San Francisco and São Paulo offices (2016); and Brasilia and Singapore offices (2017). Initially focused on emerging markets, Eurasia Group expanded to include frontier and developed economies and established practices focused on geo-technology and energy issues. Bremmer has co-authored Eurasia Group’s annual Top Risks report, a forecast of 10 geopolitical risks for the year ahead.[11][12]

Writing

[edit]Bremmer has published 11 books on global affairs, including the New York Times best-sellers, Us vs Them: The Failure of Globalism and The Power of Crisis: How Three Threats—And Our Response—Will Change the World. In addition, he is the foreign-affairs columnist and editor-at-large for Time and a contributor for the Financial Times A-List.[13]

Appointments

[edit]In 2013, he was named Global Research Professor at New York University.[14] and in 2019, Columbia University's School of International and Public Affairs announced that Bremmer would teach an Applied Geopolitics course at the school.[15]

Key concepts

[edit]J-Curve

[edit]

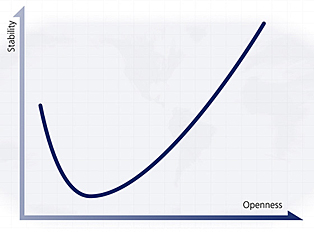

Bremmer's book, The J Curve,[16] outlines the link between a country's openness and its stability. While many countries are stable because they are open (the United States, France, Japan), others are stable because they are closed (North Korea, Cuba, Iraq under Saddam Hussein). States can travel both forward (right) and backward (left) along this J curve, so stability and openness are never secure. The J is steeper on the left-hand side, as it is easier for a leader in a failed state to create stability by closing the country than to build a civil society and establish accountable institutions; the curve is higher on the far right because states that prevail in opening their societies (Eastern Europe, for example) ultimately become more stable than authoritarian regimes. The book was listed as a top 10 pick by The Economist in 2006.[17]

State capitalism

[edit]In 2010 Bremmer published the book The End of the Free Market: Who Wins the War Between States and Corporations. Bremmer said the 2007–2008 financial crisis had made it "harder for westerners to champion a free-market system and easier for China and Russia to argue that only governments can save economies on the brink". The crisis provided evidence that "enlightened state management will offer protection from the natural excesses of free markets".[18]

G-Zero

[edit]The term G-Zero world refers to a breakdown in global leadership brought about by a decline of Western influence and the inability of other nations to fill the void.[19][20] It is a reference to a perceived shift away from the pre-eminence of the G7 industrialized countries and the expanded G20 major economies, which includes emerging powers like China, India, Brazil, Turkey, and others. In his book Every Nation for Itself: Winners and Losers in a G-Zero World (New York: Portfolio, 2012), Bremmer explains that, in the G-Zero, no country or group of countries has the political and economic leverage to drive an international agenda or provide global public goods.[21][22]

Weaponization of finance

[edit]The term weaponization of finance refers to the foreign policy strategy of using incentives (access to capital markets) and penalties (varied types of sanctions) as tools of coercive diplomacy. In his Eurasia Group Top Risks 2015 report.[23][24][25][26]

Bremmer coins the term weaponization of finance to describe the ways in which the United States is using its influence to affect global outcomes. Rather than rely on traditional elements of America's security advantage – including US-led alliances such as NATO and multilateral institutions such as the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund – Bremmer argues that the US is now "weaponizing finance" by limiting access to the American marketplace and to US banks as an instrument of its foreign and security policy.[24][26]

Pivot state

[edit]Bremmer uses pivot state to describe a nation that is able to build profitable relationships with multiple other major powers without becoming overly reliant on any one of them.[27] This ability to hedge allows a pivot state to avoid capture—in terms of security or economy—at the hands of a single country. At the opposite end of the spectrum are shadow states, frozen within the influence of a single power. Canada is an example of a pivot state: with significant trade ties with both the United States and Asia, and formal security ties with NATO, it is hedged against conflict with any single major power. Mexico, on the other hand, is a shadow state due to its overwhelming reliance on the US economy.[28][29] In Every Nation for Itself,[30] Bremmer says that in a volatile G-Zero world, the ability to pivot will take on increased importance.[citation needed]

Geopolitical recession

[edit]Bremmer coined the term “geopolitical recession” to describe the current geopolitical environment, one defined by an unwinding of the former US-led global order. Unlike economic recessions, linked to frequent boom and bust cycles, Bremmer sees geopolitical recessions as much longer cycles that are less likely to be recognized.[31] He sees the present geopolitical recession as defined by deteriorating relations between the US and its traditional allies—particularly the Europeans—as China is rising and creating an alternative international political and economic architecture. Bremmer argues that the overall result is a more fragmented approach to global governance, an increase in geopolitical tail risks, and a reduced ability to respond effectively to major international crises.[32][33]

World Data Organization

[edit]Bremmer proposed creating a “World Data Organization” to forestall a division in technology ecosystems due to conflict between the United States and China. He described it as a digital version of the World Trade Organization, arguing that the United States, Europe, Japan, and other “governments that believe in online openness and transparency” should collaborate to set standards for artificial intelligence, data, privacy, citizens’ rights, and intellectual property.[34] 2020 Democratic party presidential nominee candidate Andrew Yang expressed his support for such an organization during his campaign.[35][36]

Technopolarity

[edit]In 2021, Foreign Affairs published Bremmer's article The Technopolar Moment.[37] Drawing on the swift response by tech companies in the aftermath of the 2021 United States Capitol insurrection, Bremmer wrote that tech giants like Amazon, Apple, Facebook, Google, and Alibaba have accumulated more power than any large corporations of the past. He wrote these non state actors are now shaping geopolitics and exercise a form of sovereignty over a rapidly expanding digital space that is out of reach of national governments.[citation needed]

Other organizations

[edit]Eurasia Group Foundation

[edit]In 2016, Bremmer founded the Eurasia Group Foundation (EGF), a 501(c)3 public charity. Bremmer currently serves as the Eurasia Group Foundation’s board president.

GZERO Media

[edit]In 2017, Bremmer and Eurasia Group launched digital media company GZERO Media,[38] and a US national public television show called GZERO World with Ian Bremmer on PBS.[39] The company’s name refers to the term coined by Bremmer in Every Nation for Itself to describe a world where no country or group of countries has the political and economic leverage to drive an international agenda or provide global public goods.[40] As a part of the company's public outreach concept, they have a recurring segment, Puppet Regime, which makes use of street interviews and short narrative sketch formats using puppets.[41]

Political reporting

[edit]In March 2016, Bremmer sent a weekly note to clients where he unintentionally came up[citation needed] with the "America First" slogan used by Donald Trump. The note described then-candidate Trump's foreign policy not as isolationism but as a policy of "America First", a transactional, unilateralist perspective that was more a Chinese than American framework for foreign policy. Bremmer used the term to help explain Trump's foreign policy views and not as a campaign slogan. A few weeks later, The New York Times reporters David Sanger and Maggie Haberman, both of whom receive Bremmer's weekly note, conducted Trump’s first foreign policy interview and asked him if he would describe himself as an isolationist. He said no. They then asked Trump if he considered himself an adherent of America First. Trump said yes[42] and liked the term so much he started using it himself. Haberman later credited Bremmer with coming up with “America First” to describe Trump’s foreign policy.[43] The phrase was commonplace from the time Woodrow Wilson first used it in his 1916 campaign (see America First).

In July 2017, Bremmer broke news of a second, previously undisclosed meeting between Presidents Trump and Putin during the G20 heads of state dinner in Hamburg. He wrote about the meeting in his weekly client note and later appeared on Charlie Rose to discuss the meeting’s implications. Other major media outlets quickly picked up the news. Newsweek profiled Bremmer in an article titled "Who is Eurasia Group’s Ian Bremmer, the risk consultant who exposed the second Trump-Putin meeting?"[44] Trump initially denied that his second meeting with Putin had taken place and called Bremmer's report "fake news."[45] However, then-White House Press Secretary Sarah Huckabee Sanders later held a press conference and confirmed the second meeting had occurred.[46]

In 2019, Donald Trump posted a tweet that appeared to praise North Korean leader Kim Jong Un for criticizing rival Joe Biden: "I have confidence that Chairman Kim will keep his promise to me, & also smiled when he called Swampman Joe Biden a low IQ individual, & worse."[47] In reaction, Bremmer tweeted, "President Trump in Tokyo: 'Kim Jong Un is smarter and would make a better President than Sleepy Joe Biden.'"[48] After he was criticized on Twitter for appearing to quote Trump falsely, Bremmer acknowledged that President Trump had not spoken as Bremmer had quoted him and suggested that the statement was facetious, calling it "objectively a completely ludicrous quote."[48][49] President Trump used the incident to call for stronger libel laws.[50]

Bibliography

[edit]Books

[edit]- Soviet Nationalities Problems. (edited with Norman Naimark), (Stanford: Stanford Center for Russian and East European Studies: 1990). ISBN 0-87725-195-9

- Nations and Politics in the Soviet Successor States. (edited with Raymond Taras), (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1993). ISBN 0-521-43860-8

- New States, New Politics: Building the Post-Soviet Nations. (edited with Raymond Taras), (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1997). ISBN 0-521-57799-3

- The J Curve: A New Way to Understand Why Nations Rise and Fall. (Simon & Schuster, 2006; revised paperback, 2007). ISBN 0-7432-7471-7

- Managing Strategic Surprise: Lessons from Risk Management & Risk Assessment. (edited with Paul Bracken and David Gordon), (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2008). ISBN 0-521-88315-6

- The Fat Tail: The Power of Political Knowledge for Strategic Investing. (with Preston Keat), (New York: Oxford University Press, 2009; revised paperback, 2010). ISBN 0-19-532855-8

- The End of the Free Market: Who Wins the War Between States and Corporations. (New York: Portfolio, 2010; revised paperback 2011). ISBN 978-1-59184-301-6

- Every Nation for Itself: Winners and Losers in a G-Zero World. (New York: Portfolio, May 2012; revised paperback 2013). ISBN 978-1-59184-468-6

- Superpower: Three Choices for America's Role in the World. (New York: Portfolio, May 2015). ISBN 978-1591847472

- Us vs Them: The Failure of Globalism. (New York: Portfolio, April 2018). ISBN 978-0525533184

- The Power of Crisis: How Three Threats--And Our Response--Will Change The World. (New York: Simon and Schuster, May 2022). ISBN 978-1982167509

Articles

[edit]- Bremmer, Ian (March 2–9, 2020). "What Germany's election bump may mean for the E.U.". Time Magazine. 195 (7–8) (International ed.): 19.[a]

Notes

[edit]- ^ Online version is titled "How Germany’s election will affect the E.U."

References

[edit]- ^ a b "About GZERO Media". YouTube.

- ^ Atamian, Christopher. "Roots Shaping Worldviews". auroraprize.com. Retrieved December 12, 2021.

Ian Bremmer is only one-fourth Armenian (on his mother's side). Still, he has always treasured that part of his heritage and the Armenian community's embrace of his abilities and ambition.

- ^ Heer, Jeet (April 24, 2018). ""We're Going to See a Lot More Walls"". The New Republic. ISSN 0028-6583. Retrieved January 12, 2024.

- ^ "Of Chelsea, Nov. 21, Marie J. (Scrivano)". The Boston Globe. November 22, 2001.

Beloved mother of Ian Bremmer of NY, and Robert Coolbrith of Chelsea.

- ^ Thompson, Damian (September 30, 2006). "Here's how the world works". The Daily Telegraph. London. Archived from the original on June 30, 2008. Retrieved August 1, 2008.

- ^ a b "High School at Age Eleven". www.linkedin.com. Retrieved April 11, 2023.

- ^ ""Superpower" Excerpt by Ian Bremmer". MSNBC. May 19, 2015.

- ^ "Ian Bremmer | World Policy Institute". Worldpolicy.org. Archived from the original on December 27, 2017. Retrieved January 30, 2016.

- ^ "The politics of ethnicity : Russians in the Ukraine". Stanford University. Archived from the original on March 27, 2017. Retrieved March 27, 2017.

- ^ Harding, Luke (February 3, 2018). "Why Carter Page Was Worth Watching: There's plenty of evidence that the former Trump campaign adviser, for all his quirks, was on suspiciously good terms with Russia". Politico. Retrieved October 8, 2018.

- ^ Hargreaves, Jim. "Eurasia Group names top risks for 2012". CNN.

- ^ "The top geopolitical risks for 2019". MSNBC.

- ^ "The A-List". The Financial Times. June 2011.

- ^ "Ian Bremmer, President of Eurasia Group, Named NYU Global Research Professor". Nyu.edu. Retrieved July 19, 2017.

- ^ "Eurasia Group | Ian Bremmer returns to Columbia University Faculty". eurasiagroup.net. Retrieved September 5, 2019.

- ^ Bremmer, Ian. 2006. The J Curve: A New Way to Understand Why Nations Rise and Fall. Simon and Schuster.

- ^ "Fighting to be tops". The Economist.

- ^ "State capitalism: China's 'market-Leninism' has yet to face biggest test". Financial Times. September 13, 2010. Retrieved July 19, 2017. (subscription required)

- ^ "Eurasia Group Top 10 Risks of 2011". Eurasiagroup.net. Archived from the original on January 31, 2011. Retrieved July 19, 2017.

- ^ Gregory Scoblete. Will Free Markets Give Way to State Capitalism?, RealClearPolitics, May 28, 2010.

- ^ Ian Bremmer and David Gordon.G-Zero Archived September 12, 2011, at the Wayback Machine, Foreign Policy, January 7, 2011.

- ^ Ian Bremmer and Nouriel Roubini. A G-Zero World, Foreign Affairs, March/April 2011.

- ^ "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on January 28, 2015. Retrieved April 27, 2015.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ a b BRINK Editorial Staff (January 9, 2015). "Ian Bremmer Q&A: Top Risks of 2015". BRINK. Retrieved October 24, 2021.

- ^ Holodny, Elena (January 5, 2015). "2015 Could Be The Year We Witness The 'Weaponization Of Finance'". The Insider. Retrieved October 24, 2021.

- ^ a b Bremmer, Ian (September 23, 2015). "5 Patterns Disrupting the World". GE. Retrieved October 24, 2021.

- ^ "The Future Belongs to the Flexible". The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved July 19, 2017.

- ^ Bremmer, Ian (May 30, 2012). "Which Countries Will Rise to the Top in a Leaderless World?". Harvard Business Review. Retrieved October 24, 2021.

- ^ Foxman, Simone (May 1, 2012). < "These Are The Countries That Will Win And Lose In The New Global Paradigm". Business Insider. Retrieved October 24, 2021.

- ^ Bremmer, Ian. Every Nation for Itself

- ^ Tan, Weizhen (October 10, 2018). "A 'geopolitical recession' has arrived and the US-led world order is ending, Ian Bremmer says". CNBC. Retrieved June 24, 2019.

- ^ Bremmer, Ian (March 29, 2016). "3 Risks Poised to Disrupt a Fast-Changing World by 2021 | GE News". GE. Retrieved October 24, 2021.

- ^ Bremmer, Ian (April 7, 2021). "US-EU relations will never be the same again". BusinessLIVE. Retrieved October 24, 2021.

- ^ "Why we need a World Data Organization. Now". GZERO Media. November 25, 2019. Retrieved December 4, 2019.

- ^ Yang 🧢, Andrew (November 25, 2019). "You heard me talk about my support for a World Data Organization in last week's debate. I got the idea from @ianbremmer. Thanks Ian". Twitter. Retrieved December 4, 2019.

- ^ Everything Andrew Yang Said at the Democratic Debate in Atlanta | NBC New York, retrieved December 4, 2019

- ^ Bremmer, Ian (October 16, 2022). "The Technopolar Moment". ISSN 0015-7120. Retrieved October 26, 2022.

- ^ "GZERO Media". GZERO Media. Retrieved July 15, 2020.

- ^ GZERO WORLD with Ian Bremmer, retrieved July 15, 2020

- ^ "Coping with a G-Zero World". thediplomat.com. Retrieved July 15, 2020.

- ^ "Puppet Regime: Insecurity Counsel". Time. Retrieved May 1, 2022.

- ^ "Transcript: Donald Trump Expounds on His Foreign Policy Views". The New York Times. March 26, 2016. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved June 28, 2019.

- ^ Haberman, Maggie (March 26, 2016). ".@ianbremmer was one who identified Trump's view as "America First" a few months ago". @maggieNYT. Retrieved June 28, 2019.

- ^ EDT, Tom Porter On 7/19/17 at 9:09 AM (July 19, 2017). "Who is Ian Bremmer, the political risk consultant who broke the story of the second Trump-Putin meeting?". Newsweek. Retrieved June 28, 2019.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ "Russian lawmaker: Reports of 'secret' Putin-Trump meeting 'sick'". USA TODAY. Retrieved June 28, 2019.

- ^ "Trump, Putin had second, previously undisclosed meeting at G-20 summit". NBC News. Retrieved June 28, 2019.

- ^ Trump, Donald (May 26, 2019). ""North Korea fired off some small weapons, which disturbed some of my people, and others, but not me. I have confidence that Chairman Kim will keep his promise to me, & also smiled when he called Swampman Joe Biden a low IQ individual, & worse. Perhaps that's sending me a signal?"". Twitter. Retrieved November 2, 2020.

- ^ a b "NYU Professor Panned For Tweeting Out Fake Trump Quote". Mediaite. May 26, 2019. Retrieved May 26, 2019.

- ^ bremmer, ian (May 27, 2019). ""My tweet yesterday about Trump preferring Kim Jong Un to Biden as President was meant in jest. The President correctly quoted me as saying it was a 'completely ludicrous' statement. I should have been clearer. My apologies."". @ianbremmer. Retrieved June 25, 2019.

- ^ Rosenberg, Eli (May 27, 2019). "A political scientist caused confusion when he made up a Trump quote. The president noticed". The Washington Post. Washington DC. Retrieved May 27, 2019.

External links

[edit]- Nexstar Media Group

- 1969 births

- Living people

- American political scientists

- Columbia University faculty

- Stanford University alumni

- American international relations scholars

- Tulane University alumni

- Writers about globalization

- People from Chelsea, Massachusetts

- American people of Armenian descent

- American people of Syrian descent

- American people of German descent

- American people of Italian descent

- Carnegie Council for Ethics in International Affairs

- Time (magazine) people