Friz Freleng

Friz Freleng | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | Isadore Freleng August 21, 1905 Kansas City, Missouri, U.S. |

| Died | May 26, 1995 (aged 89) Los Angeles, California, U.S. |

| Resting place | Hillside Memorial Park Cemetery |

| Other names | I. Freleng Congressman Frizby |

| Occupations |

|

| Years active | 1923–1986[2][3] |

| Employer(s) | Disney Brothers Cartoon Studio/Walt Disney Studio (1927–1928) Screen Gems (1928–1930) Harman-Ising (1929–1933) Warner Bros. Cartoons (1933–1937, 1939–1962) MGM (1937–1939) Hanna-Barbera (1962-1963) DePatie-Freleng Enterprises (1963-1981) Warner Bros. Animation (1981–1986) |

| Spouse |

Lily Schoenfeld Freleng

(m. 1932) |

| Children | 2 |

| Signature | |

| |

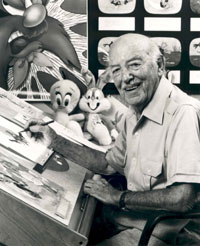

Isadore "Friz" Freleng (/ˈfriːləŋ/;[6] August 21, 1905[a] – May 26, 1995),[5] credited as I. Freleng early in his career, was an American animator, cartoonist, director, producer, and composer known for his work at Warner Bros. Cartoons on the Looney Tunes and Merrie Melodies series of cartoons from the 1930s to the early 1960s. In total he created more than 300 cartoons.

He introduced and/or developed several of the studio's biggest stars, including Bugs Bunny, Porky Pig, Tweety, Sylvester, Yosemite Sam (to whom he was said to bear more than a passing resemblance), Granny, and Speedy Gonzales. The senior director at Warners' Termite Terrace studio, Freleng directed more cartoons than any other director in the studio (a total of 266), and is also the most officially-honored of the Warner directors, having won five Academy Awards and three Emmy Awards. After Warner closed down the animation studio in 1963, Freleng and business partner David H. DePatie founded DePatie–Freleng Enterprises, which produced cartoons (including The Pink Panther Show), feature film title sequences, and Saturday-morning cartoons through the early 1980s.

The nickname "Friz" came from his friend, Hugh Harman, who initially nicknamed him "Congressman Frizby" after a fictional senator who appeared in satirical pieces in the Los Angeles Examiner, due to the character's strong resemblance to him. Over time, this shortened to "Friz".[2][10]

William Schallert claimed that Freleng was the model for Mr. Magoo due to his physical appearance.[11]

Early career

[edit]

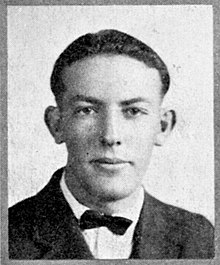

Freleng was born to Louis Mendel Freleng, a Polish Jewish immigrant from Kutno, and Elka (née Ribakoff) Freleng, a Ukrainian Jewish immigrant from Odesa Oblast,[12] in Kansas City, Missouri, where he attended Westport High School from 1919 to 1923[8] and where began his career in animation at the United Film Ad Service.[2][13] There, he made the acquaintance of fellow animators Hugh Harman and Ub Iwerks. In 1923, Iwerks' friend, Walt Disney, moved to Hollywood and put out a call for his Kansas City colleagues to join him. Freleng, however, held out until January 1927, when he finally moved to California and joined the Walt Disney studio. He worked alongside other former Kansas City animators, including Iwerks, Harman, Carman Maxwell, and Rudolf Ising. While at Disney, Freleng worked on the Alice Comedies and Oswald the Lucky Rabbit cartoons for producers Margaret Winkler and Charles Mintz. Friz said in an interview with Michael Barrier that Walt had shown patience and remorse in letters prior to joining him, but did not show that attitude after he joined Disney and instead Disney became abusive and harassed him.[2][14][13][15] In 1928, Freleng left the studio, due to Disney saying he "forfeited his bonus" along with comments on his animation mistakes. Freleng moved back to Kansas to work at his old job at the United Film Ad Service.[16]

Freleng soon teamed up with Harman and Ising (who had also left Disney's employ) to create their own studio. The trio produced a pilot film starring a new Mickey Mouse-like character named Bosko. Looking at unemployment if the cartoon failed to generate interest, Freleng moved to New York City to work on Mintz' Krazy Kat cartoons,[13][14] all the while still trying to sell the Harman-Ising Bosko picture. Freleng was very unhappy living in New York and made the best of it until another opportunity opened for him. Bosko was finally sold to Leon Schlesinger, who would produce the series for Warner Bros. At first, Freleng was reluctant to return to California when Harman-Ising asked him to work on the series. At the insistence of his sister Jean, Freleng soon moved back to California to work on the Bosko series, ultimately released under the title Looney Tunes.[13] A prominent animator on the series, Freleng was eventually delegated co-directorial duties on shorts such as Bosko's Picture Show.

Freleng as director

[edit]Early Schlesinger cartoons

[edit]Harman and Ising (alongside their crew of animators) left Schlesinger's employ over disputes about budgets in 1933. Schlesinger was left with no experienced directors and therefore lured Freleng away from Harman-Ising to successfully fix cartoons directed by Tom Palmer which Warner had rejected. The young animator rapidly became Schlesinger's top director, helming the majority of the higher-budgeted Merrie Melodies shorts during the mid-1930s, and he introduced the studio's first true post-Bosko star, Porky Pig, in the film, I Haven't Got a Hat (1935). Porky was a distinctive character, unlike Bosko or his replacement, Buddy.[13]

As a director, Freleng gained the reputation of a tough taskmaster. His unit, however, consistently produced high-quality animated shorts under his direction.[17]

Friz Freleng directed the largest number of cartoons on the Censored Eleven, a group of Looney Tunes and Merrie Melodies cartoons originally produced and released by Warner Bros. that were withheld from syndication in the United States by United Artists (UA) in 1968 because the use of ethnic stereotypes in the cartoons, specifically African stereotypes, was deemed too offensive for contemporary audiences.

David DePatie, when asked about the Japanese beetle in Blue Racer in 1996, said this about Friz's view on race, "It seems like poking fun at certain ethnic groups had always spelled success. Friz had always felt that way in his cartoons, especially with Speedy."[18]

Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer

[edit]In September 1937, Freleng left Schlesinger after accepting an increase in salary to direct for the new Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer cartoon studio headed by Fred Quimby. Freleng served as a director on The Captain and the Kids, an animated series adapted from the comic strip of the same name (an alternate version of The Katzenjammer Kids). In November 1938, Freleng became a "junior director" under Hugh Harman but quit after 6 months in April 1939.[19]

Back with Schlesinger and Warner Bros.

[edit]Freleng happily returned to Warner Bros. in mid-April 1939[20] when his MGM contract ended. One of the first Looney Tunes cartoon shorts directed by Freleng during his second tenure at the studio was You Ought to Be in Pictures, a cartoon short which blended animation with live-action footage of the Warner Bros. studio (and included staff such as story man Michael Maltese and Schlesinger himself). The plot, which centers around Porky Pig being tricked by Daffy Duck into terminating his contract with Schlesinger to attempt a career in features, echoes Freleng's experience in moving to MGM.

Directorial achievements

[edit]Schlesinger's hands-off attitude toward his animators allowed Freleng and his fellow directors almost complete creative control and room to experiment with cartoon comedy styles, which allowed the studio to keep pace with the Disney studio's technical superiority. Freleng's style quickly matured, and he became a master of comic timing. Often working alongside layout artist Hawley Pratt, he also introduced or redesigned a number of Warner characters, including Yosemite Sam in 1945, the cat-and-bird duo Sylvester and Tweety in 1947, and Speedy Gonzales in 1955.

Freleng and Chuck Jones would dominate the Warner Bros. studio in the years after World War II, with Freleng largely concentrating on the above-mentioned characters, as well as Bugs Bunny. Freleng continued to produce modernized versions of the musical comedies he animated in his early career, such as Three Little Bops (1957) and Pizzicato Pussycat (1955). He won four Oscars during his time at Warner Bros., for the films Tweetie Pie (1947), Speedy Gonzales (1955), Birds Anonymous (1957) and Knighty Knight Bugs (1958). Other Freleng cartoons, such as Sandy Claws (1955), Mexicali Shmoes (1959), Mouse and Garden (1960) and The Pied Piper of Guadalupe (1961) were Oscar nominees.

Freleng's cartoon, Show Biz Bugs (1957), with Daffy Duck vying with Bugs Bunny for theatre audience appreciation, was arguably a template for the successful format of The Bugs Bunny Show that premiered on television in the autumn of 1960. Further, Freleng directed the cartoons with the erudite and ever-so-polite Goofy Gophers encountering the relentless wheels of human industry, them being I Gopher You (1954) and Lumber Jerks (1955), and he also directed three cartoons (sponsored by the Alfred P. Sloan Foundation) extolling the virtues of free-market capitalism: By Word of Mouse (1954), Heir-Conditioned (1955) and Yankee Dood It (1956), all three of which involved Sylvester. Freleng directed all three of the vintage Warner Brothers cartoons in which a drinking of Dr. Jekyll's potion (of The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde) induces a series of monstrous transformations: Dr. Jerkyl's Hide (1954), Hyde and Hare (1955) and Hyde and Go Tweet (1960). Other Freleng fancies were man at war with the insect world (as in Of Thee I Sting (1946) and Ant Pasted (1953)), an inebriated stork delivering the wrong baby (in A Mouse Divided (1952), Stork Naked (1955) and Apes of Wrath (1959)), and characters marrying for money and finding themselves with a shrewish wife and a troublesome step-son (His Bitter Half (1949) and Honey's Money (1962)).

Freleng was occasionally the subject of in-jokes in Warner cartoons. In Canary Row (1950), there were billboards in the background of scenes advertising various products called "Friz". The "Hotel Friz" was featured in Racketeer Rabbit (1946) and "Frizby the Magician" was one of the acts Bugs Bunny pitched in High Diving Hare (1949).

Musical knowledge and technique

[edit]Freleng was somewhat of a musical composer and a classically trained violinist who timed his cartoons on musical bar sheets. Freleng would time gags that best utilized Carl Stalling's, Milt Franklyn's or William Lava's music. He was one of a very few directors at Warner Bros. to have musical knowledge for making cartoons. Every cartoon Freleng directed from the late 1930s to 1963 was made with his creative musical technique.[1]

DePatie–Freleng Enterprises

[edit]Warner Bros. Cartoons was closed in 1963, leading Freleng to take a job at Hanna-Barbera Productions as story supervisor on their first feature, Hey There, It's Yogi Bear![21][13] Freleng rented the same space from Warners to create cartoons with his now-former boss, producer David H. DePatie (the final producer hired by Warner Bros. to oversee the cartoon division), forming DePatie–Freleng Enterprises. When Warner decided to reopen their cartoon studio in 1964, due to Freleng asking them if he can rent the studio, eventually settling for $500, they did so in name only; DePatie–Freleng produced the cartoons into 1966.[13]

The DePatie–Freleng studio's signature achievement was The Pink Panther. DePatie–Freleng was commissioned to create the opening titles for the feature film The Pink Panther (1963), for which layout artist and director Hawley Pratt and Freleng created a suave, cool cat character. The Pink Panther cartoon character became so popular that United Artists, distributors of The Pink Panther, had Freleng produce a short cartoon starring the character, The Pink Phink (1964).

After The Pink Phink won the 1965 Academy Award for Best Short Subject (Cartoons), Freleng and DePatie responded by producing a whole series of Pink Panther cartoons. Other original cartoon series, among them The Inspector, The Ant and the Aardvark, Tijuana Toads, The Dogfather, Roland and Rattfink and Crazylegs Crane, soon followed. In 1969, The Pink Panther Show, a Saturday morning anthology program featuring DePatie–Freleng cartoons, debuted on NBC. The Pink Panther and the other original DePatie–Freleng series would remain in production through 1980, with new cartoons produced for simultaneous Saturday morning broadcast and United Artists theatrical release.

Layout artist Hawley Pratt, who worked at DePatie–Freleng during the time, is credited with the creation of Frito-Lay's Chester Cheetah, on the Food Network show "Deep Fried Treats Unwrapped", though some sources say it was DDB Worldwide, while others credit Brad Morgan. The studio is also known for creating the color opening title sequence for the I Dream of Jeannie television series. DePatie–Freleng also contributed special effects to the original version of Star Wars (1977), particularly the animation of the lightsaber blades, which was done by Korean animator Nelson Shin.[22][23]

By 1967, DePatie and Freleng had moved their operations to the San Fernando Valley. Their studio was located on Hayvenhurst Avenue in Van Nuys. One of their projects, titled Goldilocks, featured Bing Crosby and his family, and had songs by the Sherman Brothers. At their new facilities, they continued to produce new cartoons until 1980, when they sold DePatie–Freleng to Marvel Comics, which renamed it Marvel Productions.

Later career and death

[edit]Freleng later served as an executive producer on three 1980s Looney Tunes compilation features, The Looney Looney Looney Bugs Bunny Movie (1981), Bugs Bunny's 3rd Movie: 1001 Rabbit Tales (1982), and Daffy Duck's Fantastic Island (1983), which linked classic shorts with new animated sequences. In 1986, Freleng stepped down and gave his position at Warner Bros. to his secretary at the time, Kathleen Helppie-Shipley, who ended up being the second-longest producer of the Looney Tunes and Merrie Melodies franchise, behind only Leon Schlesinger.[2]

In 1994, the International Family Film Festival presented its first Lifetime Achievement of Excellence in Animation award to Freleng, and the award has since been referred to as the "Friz Award" in his honor.[24]

On May 26, 1995, Friz Freleng died of natural causes at the UCLA Medical Center, aged 89.[25] The WB animated TV series The Sylvester & Tweety Mysteries, and the Looney Tunes cartoon From Hare to Eternity (which was the last one directed by Chuck Jones), were both dedicated to his memory. After his death, Cartoon Network aired a variation of one of their station idents with the words "Friz Freleng: 1906–1995" (the birth year is disputed) appearing and an announcer paying tribute to Freleng and his works. He is interred in Hillside Memorial Park Cemetery.[2]

Freleng is portrayed by Taylor Gray in the film Walt Before Mickey (2015).

Partial filmography

[edit]- Alice's Picnic (Short) (animator, 1927)

- Trolley Troubles (Short) (animator, 1927)

- The Banker's Daughter (Short) (animator, 1927)

- Fiery Fireman (Short) (director and animator, 1928)

- Homeless Homer (Short) (director and animator, 1929)

- Hen Fruit (Short) (director and animator, 1929)

- The Wicked West (Short) (director, 1929)

- Weary Willies (Short) (director, 1929)

- Bosko the Talk-Ink Kid (Short) (animator – uncredited, 1929)

- Hold Anything (Short) (animator, 1930)

- Hittin' the Trail for Hallelujah Land (Short) (animator, 1931)

- Big Man from the North (Short) (animator, 1931)

- The Tree's Knees (Short) (animator, 1931)

- Battling Bosko (Short) (animator, 1932)

- Moonlight for Two (Short) (animator, 1932)

- It's Got Me Again! (Short) (animator, 1932)

- Bosko in Person (Short) (animator, 1933)

- Buddy's Day Out (Short) (story editor – uncredited; 1933)

- We're in the Money (Short) (animator, 1933)

- I Like Mountain Music (Short) (animator, 1933)

- I Haven't Got a Hat (1935) (Short) (director, 1935)

- Poultry Pirates (Short) (story – uncredited, 1938)

- The Honduras Hurricane (Short) (story – uncredited, 1938)

- Knighty Knight Bugs (1958) (Short) (director, 1958, earned John W. Burton's Academy Award for Best Animated Short Film after his death)

- Shishkabugs (Short) (director, 1962)

- The Jet Cage (Short) (writer, 1962)

- Philbert (Three's a Crowd) (Short) (animation director, 1963)

- Nuts and Volts (Short) (director, 1964)

- It's Nice to Have a Mouse Around the House (Short) (producer, 1965)

- The Wild Chase (Short) (producer, 1965)

- Tease for Two (Short) (producer, 1965)

- Cats and Bruises (Short) (director, 1965)

- The Solid Tin Coyote (Short) (producer, 1966)

- Pink Is a Many Splintered Thing (Short) (producer, 1968)

- Slink Pink (Short) (producer, 1969)

- Shot and Bothered (Short) (producer, 1969)

- The Ant and the Aardvark (Short) (producer, 1969)

- Therapeutic Pink (Short) (producer, 1977)

- Pink Press (Short) (producer, 1978)

- Pinktails for Two (Short) (producer, 1978)

- Bugs Bunny's Looney Christmas Tales (TV Short) (director of "Bugs Bunny" sequences, 1979)

Notes

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b "Irreverent Imagination: The Golden Age of Looney Tunes – video dailymotion". Dailymotion. Archived from the original on March 1, 2017. Retrieved August 2, 2019.

- ^ a b c d e f g Arnold, Mark (2015). Think Pink: The Story of DePatie-Freleng. BearManor Media. pp. unnumbered pages.

- ^ The Friz and the Diz Sampson, Wade (2006)

- ^ Cliping from the Los Angeles Times

- ^ a b "Animator Friz Freleng dead at 89". UPI. May 26, 1995.

- ^ "Friz Freleng - DOCUMENTARY Friz on Film"

- ^ 1940 census

- ^ a b "BIOGRAPHY OF FRIZ FRELENG (1905-1995), CARTOONIST AND FILM ANIMATOR". 1999. Retrieved August 6, 2022.

- ^ "Friz Freleng". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved January 6, 2014.

- ^ Sigall 2005, p. 62.

- ^ Nesteroff, Kliph William Schallert Part 1 Classic Television Showbiz

- ^ Silbiger, Steve (May 25, 2000). The Jewish Phenomenon: Seven Keys to the Enduring Wealth of a People. Taylor Trade Publishing. p. 166. ISBN 9781589794900.

- ^ a b c d e f g Archived at Ghostarchive and the Wayback Machine: "Friz Freleng at Reg Hartt's Cineforum, Toronto, Canada, 1980". YouTube. July 28, 2017.

- ^ a b "Complimentary Mintz: Krazy Kat and Toby the Pup: 1929–31". Cartoon Research. April 12, 2017. Retrieved May 29, 2020.

- ^ Barrier, Michael (1999). Hollywood cartoons : American animation in its golden age. Oxford University Press. p. 46.

- ^ The Friz and the Diz

- ^ Sigall 2005, p. 64.

- ^ "Remembering My Chat With David DePatie". Cartoon Research. October 25, 2021. Retrieved October 25, 2021.

- ^ Barrier, Michael (1999). Hollywood cartoons : American animation in its golden age. Oxford University Press. pp. 288, 291–292.

- ^ The Exposure Sheet studio newsletter, Vol. 1, No. 5 https://cartoonresearch.com/index.php/the-exposure-sheet-volumes-5-and-6/#prettyphoto[43649]/0/

- ^ Barrier, Michael (2003). Hollywood Cartoons American Animation in Its Golden Age. Oxford University Press. pp. 562–563. ISBN 978-0-19-516729-0.

- ^ Evans, Greg (October 14, 2021). "David H. DePatie Dies: 'The Pink Panther' Cartoon Co-Creator & Producer Was 91". Variety. Retrieved January 20, 2023.

- ^ Nelson Shin

- ^ "History". August 8, 2016. Archived from the original on February 9, 2019. Retrieved August 2, 2019.

- ^ "Isadore (Friz) Freleng Dies; Creator of Cartoons Was 89". The New York Times. Associated Press. May 28, 1995. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved January 30, 2022.

Sources

[edit]- Sigall, Martha (2005). "The Boys of Termite Terrace". Living Life Inside the Lines Tales from the Golden Age of Animation. University Press of Mississippi. ISBN 9781578067497.

External links

[edit] Media related to Friz Freleng at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Friz Freleng at Wikimedia Commons Works by or about Friz Freleng at Wikisource

Works by or about Friz Freleng at Wikisource- Friz Freleng at IMDb

- 1940 census record

- 1905 births

- 1995 deaths

- Age controversies

- 20th-century American artists

- 20th-century American Jews

- 20th-century American male writers

- 20th-century American screenwriters

- American animated film directors

- American animated film producers

- American male screenwriters

- American storyboard artists

- American television producers

- Animation screenwriters

- Animators from Missouri

- Artists from Kansas City, Missouri

- Burials at Hillside Memorial Park Cemetery

- Directors of Best Animated Short Academy Award winners

- Film directors from Missouri

- Film producers from Missouri

- Jewish American animators

- Jewish film people

- Jewish American screenwriters

- American people of Polish-Jewish descent

- American people of Ukrainian-Jewish descent

- Laugh-O-Gram Studio people

- Hanna-Barbera people

- Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer cartoon studio people

- Producers who won the Best Animated Short Academy Award

- Primetime Emmy Award winners

- Screenwriters from Missouri

- Television producers from Missouri

- Walt Disney Animation Studios people

- Warner Bros. Cartoons directors