1898 Georgia hurricane

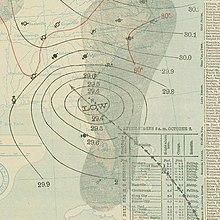

Surface weather analysis of the hurricane on October 2 | |

| Meteorological history | |

|---|---|

| Formed | September 25, 1898 |

| Dissipated | October 6, 1898 |

| Category 4 major hurricane | |

| 1-minute sustained (SSHWS/NWS) | |

| Highest winds | 130 mph (215 km/h) |

| Lowest pressure | 938 mbar (hPa); 27.70 inHg |

| Overall effects | |

| Fatalities | At least 179 |

| Damage | $1.5 million (1898 USD) |

| Areas affected | Georgia (landfall), Florida, Midwestern United States Atlantic Canada |

| IBTrACS | |

Part of the 1898 Atlantic hurricane season | |

The 1898 Georgia hurricane was a major hurricane that hit the U.S. state of Georgia, as well as the strongest on record in the state. It was first observed on September 29, although modern researchers estimated that it developed four days earlier to the east of the Lesser Antilles. The hurricane maintained a general northwest track throughout its duration, and it reached peak winds of 130 mph (210 km/h) on October 2. That day, it made landfall on Cumberland Island in Camden County, Georgia, causing record storm surge flooding. The hurricane caused heavy damage throughout the region, and killed at least 179 people. Impact was most severe in Brunswick, where a 16 ft (4.9 m) storm surge was recorded. Overall damage was estimated at $1.5 million (1898 USD), most of which occurred in Georgia. In extreme northeastern Florida, strong winds nearly destroyed the city of Fernandina, while light crop damage was reported in southern South Carolina. After moving ashore, the hurricane quickly weakened and traversed much of North America; it continued northwestward until reaching the Ohio Valley and turning northeastward, and it was last observed on October 6 near Newfoundland.

Meteorological history

[edit]

Tropical storm (39–73 mph, 63–118 km/h)

Category 1 (74–95 mph, 119–153 km/h)

Category 2 (96–110 mph, 154–177 km/h)

Category 3 (111–129 mph, 178–208 km/h)

Category 4 (130–156 mph, 209–251 km/h)

Category 5 (≥157 mph, ≥252 km/h)

Unknown

On September 28, 1898, island stations in the Lesser Antilles indicated the presence of a tropical cyclone, which was confirmed by the next day.[1] Modern researchers determined that the system developed on September 25 about 220 miles (350 km) east of Guadeloupe. For most of its duration, the system maintained a northwest track, reaching hurricane status on September 27. Later that day, a barometric pressure of 977 mbar, suggesting winds of 90 mph (140 km/h). Its intensification rate slowed on September 28, before strengthening continued on October 1. The winds reached 115 mph (185 km/h), which is the equivalent of a major hurricane, or Category 3 on the Saffir-Simpson scale.[2] Around that time, the hurricane turned toward more to the west-northwest, due to a large ridge across the western Atlantic.[1]

On October 2, the hurricane continued toward the west-northwest, approaching the southeastern United States.[2] That day, it made landfall on Cumberland Island in Camden County, Georgia, and initially was thought to have done so as a Category 2 on the Saffir-Simpson scale.[3] A storm surge of 16 ft (4.9 m) was observed in Brunswick, Georgia, suggesting a central pressure of 938 mbar based on the SLOSH model.[2] Such intensity ranked the hurricane tied for the 16th strongest United States landfall, as well as the strongest in the state of Georgia. It is also the most recent major hurricane to hit the state. Additionally, its radius of maximum wind was estimated at 20 miles (32 km).[2] Almost a century after the hurricane, researchers estimated the hurricane made landfall with winds of 135 mph (217 km/h), a Category 4 on the Saffir-Simpson scale.[3] After making landfall, the hurricane quickly weakened, deteriorating to tropical storm status within 12 hours. After moving across Georgia, the storm weakened further to tropical depression status over northeastern Alabama on October 3. It continued northwestward through the Ohio Valley before recurving northeastward, accelerating through southeastern Canada and later dissipating over Newfoundland on October 6.[2]

Impact

[edit]

On October 1, a day before the hurricane moved ashore, the U.S. Weather Bureau issued northeast storm signals from Key West, Florida, to Norfolk, Virginia. Similar warnings were issued in the hours preceding the hurricane moving ashore. The advisories were credited with saving dozens of lives and millions of dollars in shipping cargo, due to advance warning for boats to remain ashore.[1]

Before the hurricane made landfall in Georgia, it produced strong winds in northeastern Florida, reaching Category 2 strength on the Saffir-Simpson scale.[2] The worst effects from the storm were confined to a very small portion of extreme northeastern Florida. At Fernandina Beach, the storm surge was estimated at 12 ft (3.7 m), causing extensive flooding in the city.[4] The October 1898 Monthly Weather Review described Fernandina as "nearly destroyed", and most anchored boats were sunk or washed inland into the marshes. Damage along the coastline reached as far south as Mayport.[1] The hurricane was small,[2] and despite passing 50 miles (80 km) northeast of Jacksonville, produced only 60 mph (97 km/h) winds in the city.[1] However, for the first time in the history of the city, all communications were cut between Jacksonville and cities further north, such as New York.[5] Damage throughout the state was estimated at $500,000 (1898 USD).[1]

The hurricane made landfall on Cumberland Island with winds estimated at 135 mph (217 km/h). It produced record storm surges across the coastline, including a 16 ft (4.9 m) report in Brunswick.[4] There, damage was heaviest, and most buildings were flooded. Similar impact was reported in Darien, where 32 people were killed. One coastal location reported the hurricane as causing the worst flooding since 1812.[1] Flooding and extensive damage occurred on Sapelo Island, including the destruction of First African Baptist Church and Behavior Cemetery.[6][7] Further north, all of Hutchinson Island in the Savannah River was covered with up to 8 ft (2.4 m) of water. The storm surge flooding entered warehouses and storage areas all along the coast, leaving many small ships wrecked or sunk. Heavy damage also occurred to coastal wharves and houses. According to the Savannah Weather Bureau office, about 5,000 barrels of rosin were dispersed, and 60,000 bushels of rice were wrecked. Winds in the city reached 60 mph (97 km/h), and the flooding severely damaged the railway to nearby Tybee Island.[1] Along the Blackbeard Island National Wildlife Refuge, the hurricane destroyed a hospital that helped people afflicted with yellow fever.[8] A total of 179 people were killed along the Georgia coast,[4] and damage totaled around $1 million (1898 USD).[1] In South Carolina, the hurricane produced gusty winds and storm surge flooding. Some slight damage occurred at Port Royal, and in the southern portion of the state, the high tides left damage to rice and cotton crops. The Charleston Weather Bureau reported that "a number of persons were drowned along the South Carolina coast".[1] Heavy rainfall was reported across northeast Florida, Georgia, and the western Carolinas. The highest amount recorded was 12.5 inches (320 mm) at Highlands, North Carolina.[9]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h i j E.B. Garriott (1898). "October, 1898 Monthly Weather Review" (PDF). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved 2010-11-26.

- ^ a b c d e f g Chris Landsea (2009). "Documentation of Atlantic Tropical Cyclones Changes in HURDAT". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved 2010-11-26.

- ^ a b Al Sandrik and Brian Jarvinen (2003). "A Reevaluation of the Georgia and Northeast Florida Tropical Cyclone of 2 October 1898". Jacksonville, FL National Weather Service. Retrieved 2010-11-26.

- ^ a b c Al Sandrik and Chris Landsea (2003). "Chronological Listing of Tropical Cyclones affecting North Florida and Coastal Georgia 1565–1899". Hurricane Research Division. Archived from the original on 7 December 2010. Retrieved 2010-11-27.

- ^ Charles Hesser (1974-09-18). "Hurricanes of 50 Years Pictures in News Pages". Miami Daily News. Retrieved 2011-10-04.

- ^ Kenneth H. Thomas, Jr. (July 17, 1996). "National Register of Historic Places Registration: First African Baptist Church at Raccoon Bluff / Raccoon Bluff Church". National Park Service. Retrieved January 27, 2017.

- ^ Kenneth H. Thomas, Jr. (July 17, 1996). "National Register of Historic Places Registration: Behavior Cemetery". National Park Service. Retrieved January 27, 2017. with photos

- ^ Tonya D. Clayton (1992). Living with the Georgia Shore. Durham and London: Duke University Press. p. 87. ISBN 0822312190. Retrieved 2011-10-04.

- ^ United States Army Corps of Engineers (1945). Storm Total Rainfall In The United States. War Department. p. SA 3–7.