1881 Atlantic hurricane season

| 1881 Atlantic hurricane season | |

|---|---|

Season summary map | |

| Seasonal boundaries | |

| First system formed | August 1, 1881 |

| Last system dissipated | September 24, 1881 |

| Strongest storm | |

| Name | Five |

| • Maximum winds | 105 mph (165 km/h) (1-minute sustained) |

| • Lowest pressure | 970 mbar (hPa; 28.64 inHg) |

| Seasonal statistics | |

| Total storms | 7 |

| Hurricanes | 4 |

| Major hurricanes (Cat. 3+) | 0 |

| Total fatalities | 700 |

| Total damage | Unknown |

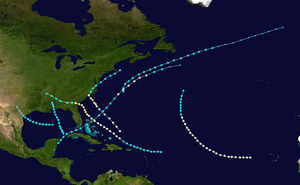

The 1881 Atlantic hurricane season ran through the summer and early fall of 1881. This is the period of each year when most tropical cyclones form in the Atlantic basin. In the 1881 Atlantic season there were three tropical storms and four hurricanes, none of which became major hurricanes (Category 3+). However, in the absence of modern satellite and other remote-sensing technologies, only storms that affected populated land areas or encountered ships at sea were recorded, so the actual total could be higher. An undercount bias of zero to six tropical cyclones per year between 1851 and 1885 and zero to four per year between 1886 and 1910 has been estimated.[1] Of the known 1881 cyclones, Hurricane Three and Tropical Storm Seven were both first documented in 1996 by Jose Fernandez-Partagas and Henry Diaz. They also proposed changes to the known tracks of Hurricane Four and Hurricane Five.[2]

Season summary

[edit]

| Deadliest United States hurricanes | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Rank | Hurricane | Season | Fatalities |

| 1 | 4 "Galveston" | 1900 | 8,000–12,000 |

| 2 | 4 "San Ciriaco" | 1899 | 3,400 |

| 3 | 4 Maria | 2017 | 2,982 |

| 4 | 5 "Okeechobee" | 1928 | 2,823 |

| 5 | 4 "Cheniere Caminada" | 1893 | 2,000 |

| 6 | 3 Katrina | 2005 | 1,392 |

| 7 | 3 "Sea Islands" | 1893 | 1,000–2,000 |

| 8 | 3 "Indianola" | 1875 | 771 |

| 9 | 4 "Florida Keys" | 1919 | 745 |

| 10 | 2 "Georgia" | 1881 | 700 |

| Reference: NOAA, GWU[3][4][nb 1] | |||

The Atlantic hurricane database (HURDAT) recognizes seven tropical cyclones for the 1881 season. Of the seven systems, four intensified into a hurricane, but none strengthened into a major hurricane.[5] José Fernández-Partagás and Henry F. Diaz first documented the third and seventh systems in their 1996 re-analysis of the season. In 2003, the Atlantic hurricane reanalysis project only made a significant track revision to the sixth storm. A reanalysis by climate researcher Michael Chenoweth, published in 2014, adds six storms and removes one, the second system. Chenoweth's study utilizes a more extensive collection of newspapers and ship logs, as well as late 19th century weather maps for the first time, in comparison to previous reanalysis projects. However, Chenoweth's proposals have yet to be incorporated into HURDAT.

Based on observations, the track of the first known system begins over the southeastern Gulf of Mexico on August 1. A few days later, the storm struck the Gulf Coast of the United States and caused flooding in the region. Four other cyclones formed in August, all but one of which impacted land. Most notably, the season's fifth cyclone peaked as a Category 2 hurricane on the Saffir–Simpson scale with sustained winds of 105 mph (165 km/h) and a minimum atmospheric pressure of 970 mbar (29 inHg). That storm caused several deaths due to maritime incidents prior to making landfall in Georgia. Overall, it caused more than $1.7 million in damage and approximately 700 fatalities, making it one of the deadliest hurricanes in the United States.

At least two additional storms developed in September. The first of the two, the season's sixth cyclone, reached an intensity similar to the fifth system. An unknown number of people drowned after it sank the Anne J. Palmer. After striking North Carolina, the hurricane caused severe damage over coastal portions of the state, totaling about $100,000. On September 18, the final known cyclone was first noted northwest of Bermuda. Moving generally northeastward, the storm transitioned into an extratropical cyclone on September 22.

The season's activity was reflected with an accumulated cyclone energy (ACE) rating of 59, ahead of only 1885 and tied with 1882 for the lowest total of the 1880s. ACE is a metric used to express the energy used by a tropical cyclone during its lifetime. Therefore, a storm with a longer duration will have higher values of ACE. It is only calculated at six-hour increments in which specific tropical and subtropical systems are either at or above sustained wind speeds of 39 mph (63 km/h), which is the threshold for tropical storm intensity. Thus, tropical depressions are not included here.[6]

Systems

[edit]Tropical Storm One

[edit]| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | August 1 – August 4 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 60 mph (95 km/h) (1-min); |

Observations suggest the presence of a tropical storm over the southern Gulf of Mexico on August 1.[2] The storm moved generally north-northwestward across the Gulf of Mexico before striking Dauphin Island, Alabama, and then near the Alabama-Mississippi state line on August 3 with winds of 60 mph (95 km/h).[5] An assessment of the storm by the Atlantic hurricane reanalysis project estimated that it weakened to a tropical depression early the following day, shortly before dissipating over east-central Mississippi.[7]

Heavy rains fell along the Gulf Coast of the United States, including up to 15.8 in (400 mm) from August 2 to August 5 in Pensacola, Florida.[2] Floodwaters reached 3 ft (0.91 m) above ground in the nearby community of Millview, forcing residents to evacuate. The storm also beached a few fishing smacks and the schooner Ella, which was loaded with a cargo of lumber.[8]

Tropical Storm Two

[edit]| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | August 11 – August 14 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 45 mph (75 km/h) (1-min); |

A tropical storm hit Corpus Christi, Texas in the middle of August, but caused no reported deaths. Signals were blown down at the harbor, and one boat was lost.[9] Climate researcher Michael Chenoweth could not confirm the existence of this system as a tropical cyclone, noting "No storm in Texas press accounts" and that Gordon E. Dunn and Banner I. Miller's 1960 reanalysis misdated a hurricane in 1880.[10]

Hurricane Three

[edit]| Category 1 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | August 11 – August 18 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 90 mph (150 km/h) (1-min); |

From August 11 to August 16, a Category 1 hurricane existed in the tropical Atlantic before turning northward and weakening. It continued northward as a tropical storm throughout August 17 and 18.[5]

Hurricane Four

[edit]| Category 1 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | August 16 – August 21 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 80 mph (130 km/h) (1-min); |

A tropical storm developed on August 16 off the eastern coast of the Yucatán Peninsula. It tracked northeastward throughout its lifetime, passing through Cuba, the Florida Keys, and the Bahamas before becoming a hurricane on August 19. It weakened to a tropical storm on August 21 and became extratropical the same day.[5]

Hurricane Five

[edit]| Category 2 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | August 21 – August 29 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 105 mph (165 km/h) (1-min); 970 mbar (hPa) |

The Georgia Hurricane of 1881

The Atlantic hurricane best track begins the path for this storm just east of the Lesser Antilles on August 21, one day before the cyclone passed north of the islands. Moving northwestward, the system intensified, reaching hurricane status early on August 24. The hurricane passed northeast of the Abaco Islands in the Bahamas two days later and strengthened into a Category 2 hurricane on the present-day Saffir–Simpson scale, peaking with maximum sustained winds of 105 mph (165 km/h). After moving north-northwestward late on August 26 and early the next day, the storm then turned west-northwestward. Around 02:00 UTC on August 28, the hurricane made landfall in Georgia between St. Simons Island and Savannah, likely at the same intensity.[5] Upon the cyclone moving ashore, the Atlantic hurricane reanalysis project estimated that it had a barometric pressure of 970 mbar (29 inHg).[7] Thereafter, the storm briefly moved westward and quickly weakened to a tropical storm within 10 hours of moving inland. By early on August 29, the system turned northwestward and weakened to a tropical depression later that day, before dissipating near the Arkansas-Mississippi state line.[5]

Between August 26 and August 27, the ship Sandusky encountered the storm, with the loss of all but two people, while most of the crew of the Hannah M. Lallis also drowned.[2] Landfall coincided with high tide and proved very destructive as several barrier islands were completely submerged by storm surge.[11] In Savannah, Georgia, few structures escaped damage, with the Monthly Weather Review noting that "nearly every house received a copious supply of salt water." in the Bohanville section of the city. A number of streets were blocked, especially by large trees and the remnants of tin roofs. Property damage in the city reached about $1.5 million. Approximately 100 ships capsized in the vicinity of Savannah.[12] A barometric recorded a pressure of 984.76 mbar (29.08 inHg), while a wind speed of 80 mph (130 km/h) was observed before the anemometer was destroyed. At least 335 people died in Savannah alone.[11] Tybee Island was also among the localities severely impacted. There, the storm demolished rows of cottages and even some of the sturdiest homes. Additionally, South Carolina experienced extensive coastal flooding. In Charleston, several feet of water submerged areas east of East Bay Street and inundated many properties in the southwest sections of city. Substantial damage to businesses, fences, roofs, telegraph wires, and trees were also reported. Damage in the city ranged from $200,000 to $300,000.[12] Overall, the storm caused an estimated 700 fatalities, making the hurricane among the deadliest to strike the United States.[13]

Hurricane Six

[edit]| Category 2 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | September 7 – September 11 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 105 mph (165 km/h) (1-min); ≤975 mbar (hPa) |

The Anne J. Palmer first encountered this storm on September 7 before capsizing in rough seas that day.[2] Thus, the track for this cyclone begins at that time to the northeast of the Turks and Caicos Islands as a Category 1 hurricane. Moving northeastward, the storm intensified slightly, becoming a Category 2 hurricane with winds of 105 mph (165 km/h) early on September 9, several hours prior to making landfall in present-day Oak Island, North Carolina.[5] The Atlantic hurricane reanalysis project estimated that upon landfall, the storm had a barometric pressure of 975 mbar (28.8 inHg).[7] Rapidly weakening to a tropical storm by early on September 10, the cyclone then turned northeastward, passing close to Wilmington–Wrightsville Beach area and later near Norfolk, Virginia, before re-emerging into the Atlantic that day. The cyclone was last noted only 50 mi (80 km) offshore Massachusetts on September 11.[5]

An unknown number of deaths occurred when the Anne J. Palmer capsized, with only one person surviving.[2] In North Carolina, the storm uprooted trees and demolished buildings at both Smithville (present-day Southport) and Wilmington. An anemometer at Wilmington indicate sustained windspeeds of 90 mph (150 km/h) before it was destroyed.[14] At least 600 bushels of peanuts suffered damage after a warehouse lost its roof. Wilmington also entirely lost communications outside the city after winds toppled many telephone and telegraph wires.[15] Damage in North Carolina totaled approximately $100,000.[14] The hurricane weakened to a tropical storm over land, bringing heavy, yet beneficial, precipitation to other states, including the first rainfall in Washington, D.C. in 33 days.[16]

Tropical Storm Seven

[edit]| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | September 18 – September 22 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 70 mph (110 km/h) (1-min); |

A tropical storm was first seen on September 18 to the northwest of Bermuda. It tracked to the northeast, reaching a peak of 70 mph (113 km/h) on the 19th while southeast of the Canadian Maritimes. It weakened over the north Atlantic, becoming extratropical on the 22nd and finally dissipating by September 24.[5]

Other storms

[edit]Chenoweth proposed six storms not currently listed in HURDAT:[10]

- August 23 to September 6, peaked as a tropical storm

- August 27 to August 29, peaked as a tropical storm

- October 15 to October 17, peaked as a tropical storm

- October 16 to October 23, peaked as a Category 3 hurricane

- November 9 to November 18, peaked as a Category 1 hurricane

- December 7 to December 8, peaked as a tropical storm

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ The storm category color indicates the intensity of the hurricane when landfalling in the U.S.

References

[edit]- ^ Landsea, C. W. (2004). "The Atlantic hurricane database re-analysis project: Documentation for the 1851–1910 alterations and additions to the HURDAT database". In Murname, R. J.; Liu, K.-B. (eds.). Hurricanes and Typhoons: Past, Present and Future. New York: Columbia University Press. pp. 177–221. ISBN 0-231-12388-4.

- ^ a b c d e f Partagas, J.F. and H.F. Diaz, 1996a "A reconstruction of historical Tropical Cyclone frequency in the Atlantic from documentary and other historical sources Part III: 1881–1890" Climate Diagnostics Center, NOAA, Boulder, Colorado

- ^ Blake, Eric S; Landsea, Christopher W; Gibney, Ethan J (August 10, 2011). The deadliest, costliest and most intense United States tropical cyclones from 1851 to 2010 (and other frequently requested hurricane facts) (PDF) (NOAA Technical Memorandum NWS NHC-6). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. p. 47. Archived (PDF) from the original on May 17, 2024. Retrieved August 10, 2011.

- ^ "Ascertainment of the Estimated Excess Mortality from Hurricane María in Puerto Rico" (PDF). Milken Institute of Public Health. August 27, 2018. Archived (PDF) from the original on August 29, 2018. Retrieved August 28, 2018.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i "Atlantic hurricane best track (HURDAT version 2)" (Database). United States National Hurricane Center. April 5, 2023. Retrieved October 28, 2024.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ North Atlantic Hurricane Basin (1851-2022) Comparison of Original and Revised HURDAT. Hurricane Research Division; Atlantic Oceanographic and Meteorological Laboratory (Report). Miami, Florida: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. April 2023. Retrieved October 15, 2024.

- ^ a b c Christopher W. Landsea; et al. (May 2015). "Documentation of Atlantic Tropical Cyclones Changes in HURDAT". National Hurricane Center, Hurricane Research Division. Retrieved April 3, 2024.

- ^ "Storm at Pensacola". The Daily Picayune. New Orleans, Louisiana. August 6, 1881. p. 1. Retrieved April 22, 2024 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ David Roth (2010-02-04). "Texas Hurricane History" (PDF). National Weather Service. Retrieved 2011-06-22.

- ^ a b Chenoweth, Michael (December 2014). "A New Compilation of North Atlantic Tropical Cyclones, 1851–98". Journal of Climate. 27 (12). American Meteorological Society: 8682. Bibcode:2014JCli...27.8674C. doi:10.1175/JCLI-D-13-00771.1. Retrieved April 29, 2024.

- ^ a b Al Sandrik; Christopher W. Landsea (2003). "Chronological Listing of Tropical Cyclones affecting North Florida and Coastal Georgia 1565-1899". Hurricane Research Division. Archived from the original on December 6, 2006. Retrieved April 3, 2024.

- ^ a b "Barometric Pressure" (PDF). Monthly Weather Review. 9 (8). August 1881. Bibcode:1881MWRv....9RR..1.. doi:10.1175/1520-0493(1881)98[1b:BP]2.0.CO;2. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 3, 2017. Retrieved April 3, 2024.

- ^ Edward N. Rappaport; José Fernández-Partagás (1996). "The Deadliest Atlantic Tropical Cyclones, 1492–1996: Cyclones with 25+ deaths". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved April 3, 2024.

- ^ a b Hudgins, James E. (April 2000). Tropical cyclones affecting North Carolina since 1586: An historical perspective. National Weather Service (Report). Blacksburg, Virginia: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. p. 15-16. Retrieved April 21, 2023.

- ^ "Yesterday's Hurricanes". The Morning Star. Wilmington, North Carolina. September 10, 1881. p. 1. Retrieved April 21, 2024 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Roth, David; Cobb, Hugh (July 16, 2001). "Late Nineteenth Century Virginia Hurricanes". Virginia Hurricane History (Report). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Archived from the original on January 8, 2008. Retrieved April 21, 2024.