Hurricane David

David at peak intensity near landfall in Hispaniola on August 31, 1979 | |

| Meteorological history | |

|---|---|

| Formed | August 25, 1979 |

| Extratropical | September 6, 1979 |

| Dissipated | September 8, 1979 |

| Category 5 major hurricane | |

| 1-minute sustained (SSHWS/NWS) | |

| Highest winds | 175 mph (280 km/h) |

| Lowest pressure | 924 mbar (hPa); 27.29 inHg |

| Overall effects | |

| Fatalities | 2,078 |

| Damage | $1.54 billion (1979 USD) |

| Areas affected | Lesser Antilles, Hispaniola, Puerto Rico, Dominica, Dominican Republic, Haiti, Cuba, The Bahamas, East Coast of the United States, Atlantic Canada |

| IBTrACS | |

Part of the 1979 Atlantic hurricane season | |

Hurricane David was a devastating Atlantic hurricane which caused massive loss of life in the Dominican Republic in August 1979, and was the most intense hurricane to make landfall in the country in recorded history. A long-lived Cape Verde hurricane, David was the fourth named storm, second hurricane, and first major hurricane of the 1979 Atlantic hurricane season.

David formed on August 25, in the eastern tropical Atlantic Ocean near Cape Verde off the coast of West Africa. Two days later, the storm reached hurricane strength, then underwent rapid intensification, strengthening into a Category 5 hurricane and reaching peak sustained winds of 175 mph (282 km/h) on August 28. By the time the system dissipated on September 8, it had traversed the Leeward Islands, Greater Antilles, The Bahamas, the East Coast of the United States, and Atlantic Canada.

David was the first hurricane to affect the Lesser Antilles since Hurricane Inez in 1966. With winds of 175 mph (282 km/h), David was one of only 2 storms of Category 5 intensity to make landfall on the Dominican Republic in the 20th century, the other also being Inez, and the deadliest since the 1930 San Zenón hurricane, killing over 2,000 people in its path. In addition, David was the deadliest tropical cyclone to hit the island of Dominica since the 1834 Padre Ruíz hurricane, which killed over 200 people.[1]

Meteorological history

[edit]

Tropical storm (39–73 mph, 63–118 km/h)

Category 1 (74–95 mph, 119–153 km/h)

Category 2 (96–110 mph, 154–177 km/h)

Category 3 (111–129 mph, 178–208 km/h)

Category 4 (130–156 mph, 209–251 km/h)

Category 5 (≥157 mph, ≥252 km/h)

Unknown

On August 25, the US National Hurricane Center reported that a tropical depression had developed within an area of disturbed weather, which was located about 870 mi (1,400 km) to the southeast of the Cape Verde Islands.[2] During that day the depression gradually developed further as it moved westwards, under the influence of the subtropical ridge of high pressure that was located to the north of the system before during the next day the NHC reported that the system had become a tropical storm and named it David. Becoming a hurricane on August 27, it moved west-northwestward before entering a period of rapid intensification which brought it to an intensity of 150 mph (240 km/h) on August 28. Slight fluctuations in intensity occurred before the hurricane ravaged the tiny windward Island of Dominica on the following day.[3] David continued west-northwest, and intensified into a Category 5 hurricane in the northeast Caribbean Sea, reaching peak intensity with maximum sustained winds of 175 mph (282 km/h) and minimum central pressure of 924 mbar (27.3 inHg) on August 30. An upper-level trough pulled David northward into Hispaniola as a Category 5 hurricane on the August 31. The eye passed almost directly over Santo Domingo, the capital of the Dominican Republic. David crossed over the island and emerged as a weak hurricane after drenching the islands.[3]

After crossing the Windward Passage, David struck eastern Cuba as a minimal hurricane on September 1. It weakened to a tropical storm over land, but quickly re-strengthened as it again reached open waters. David turned to the northwest along the western periphery of the subtropical ridge, and re-intensified to a Category 2 hurricane while over the Bahamas, where it caused heavy damage. Despite initial forecasts of a projected landfall in Miami, Florida, the hurricane turned to the north-northwest just before landfall to strike near West Palm Beach, Florida, on September 3. It paralleled the Florida coastline just inland until emerging into the western Atlantic Ocean at New Smyrna Beach, Florida, later on September 3. David continued to the north-northwest, and made its final landfall just south of Savannah, Georgia, as a minimal hurricane with 80 miles per hour (130 km/h) winds on September 5. It turned to the northeast while weakening over land, and became extratropical on September 6 over New York. As an extratropical storm, David continued to the northeast over New England and the Canadian Maritimes.[3] David intensified once more as it crossed the far north Atlantic, clipping northwestern Iceland before moving eastward well north of the Faroe Islands on September 10.[4]

Preparations

[edit]In the days prior to hitting Dominica, David was originally expected to hit Barbados and spare Dominica in the process. However, on August 29 a turn in the hours before moving through the area caused the 150 mph (240 km/h) hurricane to make a direct hit on the southern part of Dominica.[5] Even as it became increasingly clear that David was headed for the island, residents did not appear to take the situation seriously. This can be partly attributed to the fact that local radio warnings were minimal and disaster preparedness schemes were essentially non-existent. Furthermore, Dominica had not experienced a major hurricane since 1930, thus leading to complacency amongst much of the population. This proved to have disastrous consequences for the island nation.[5][6]

Some 400,000 people evacuated in the United States in anticipation of David,[3] including 300,000 people in southeastern Florida due to a predicted landfall between the Florida Keys and Palm Beach. Of those, 78,000 fled to shelters, while others either stayed at a friend's house further inland or traveled northward. Making landfall during Labor Day weekend, David forced the cancellations of many activities in the greater Miami area.[7]

Impact

[edit]| Region | Deaths | Damage | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dominica | 56 | [3] | |

| Martinique | None | $50 million | [3][8] |

| Guadeloupe | None | $100 million | [8] |

| Puerto Rico (U.S.) | 7 | $70 million | [3] |

| Dominican Republic | 2,000 | $1 billion | [3] |

| United States | 15 | $320 million | [3] |

| Totals: | 2,078 | $1.54 billion |

David is believed to have been responsible for 2,078 deaths, making it one of the deadliest hurricanes of the modern era. It caused torrential damage across its path, most of which occurred in the Dominican Republic where the hurricane made landfall as a Category 5 hurricane.

Dominica

[edit]During the storm's onslaught, David dropped up to 10 in (250 mm) of rain, causing numerous landslides on the mountainous island.[9] Hours of hurricane-force winds severely eroded the coastlines and washed out coastal roads.[5]

Damage was greatest in the southwest portion of the island, especially in the capital city, Roseau, which resembled an air raid target after the storm's passage. Strong winds from Hurricane David destroyed or damaged 80 percent of the homes (mostly wood) on the island,[6] leaving 75 percent of the population homeless,[9] with many others temporarily homeless in the immediate aftermath.[5] In addition, the rainfall turned rivers into torrents, sweeping away everything in their path to the sea.[6] Power lines were completely ripped out, causing the water system to stop as well.

Most severely damaged was the agricultural industry. The worst loss in agriculture was from bananas and coconuts, of which about 75 percent of the crop was destroyed.[9] Banana fields were completely destroyed, and in the southern portion of the island most coconut trees were blown down. Citrus trees fared better, due to the small yet sturdy nature of the trees.[5] In addition, David's winds uprooted many trees on the tops of mountains, leaving them bare and damaging the ecosystem by disrupting the water levels.[6]

In all, 56 people died in Dominica and 180 were injured.[3][9] Property and agricultural damage figures in Dominica are unknown.[3]

Lesser Antilles

[edit]

Aside from Dominica, other islands in the Lesser Antilles experienced minor to moderate damage. Just to the south of Dominica, David brought Martinique winds of up to 100 and 140 mph (160 and 230 km/h) sustained gust in the northeast of the coast of the Caravelle. The capital, Fort-de-France, reported wave heights of 15 ft (4.6 m) and experienced strong tropical storm sustained winds at 56 mph (90 km/h) and gust at 78 mph (126 km/h). David's strong winds caused severe crop damage, mostly to bananas, amounting to $50 million in losses. Though no deaths were reported, the hurricane caused 20 to 30 injuries and left 500 homeless.[9]

Guadeloupe experienced moderate to extensive damage on Basse-Terre Island. There, the banana crop was completely destroyed, and combined with other losses, crop damage amounted to $100 million. David caused no deaths, a few injuries, and left several hundred homeless. Nearby, Marie-Galante and Les Saintes reported some extreme damage while Grande-Terre had some moderate damages.[9]

The island of St. Croix in the U.S. Virgin Islands experienced significant rainfall amounting to 10–12 in (250–300 mm), but fairly minor flooding.[9]

Puerto Rico

[edit]

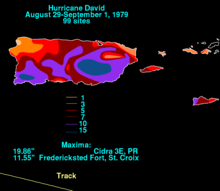

Hurricane David was originally forecasted to hit the south coast of the United States Territory of Puerto Rico, but a change of course in the middle of the night spared it the damage that the Dominican Republic suffered.

Though it did not hit Puerto Rico, Hurricane David passed less than 100 mi (160 km) south of the island, bringing strong winds and heavy rainfall to the island. Portions of southwestern Puerto Rico experienced sustained winds of up to 85 mph (137 km/h), while the rest of the island received tropical storm-force winds. While passing by the island, the hurricane caused strong seas[10] and torrential rainfall, amounting to 19.9 in (510 mm) in Mayagüez and up to 20 in (510 mm) in the central mountainous region.[3]

Despite remaining offshore, most of the island felt David's effects. Agricultural damage was severe, and combined with property damage, the hurricane was responsible for $70 million in losses.[3][9] Following the storm, the FEMA declared the island a disaster area. In all, Hurricane David killed seven people in Puerto Rico, four of which resulted from electrocutions.[9]

Dominican Republic

[edit]Upon making landfall in the Dominican Republic, David turned unexpectedly to the northwest, causing 125 mph (201 km/h) winds in Santo Domingo and Category 5 winds elsewhere in the country. The storm caused torrential rainfall, resulting in extreme river flooding.[3] The flooding swept away entire villages and isolated communities during the storm's onslaught. A rail-mounted container crane collapsed in Rio Haina at the sea-land terminal. Many roads in the country were either damaged or destroyed from the heavy rainfall, especially in the towns of Jarabacoa, San Cristobal, and Baní.[9]

Nearly 70% of the country's crops were destroyed from the torrential flooding.[11] Extreme river flooding resulted in most of the country's 2,000 fatalities.[3] One particularly deadly example of this was when a rampaging river in the mountainous village of Padre las Casas swept away a church and a school, killing several hundred people who were sheltering there.[11] The flooding destroyed thousands of houses, leaving over 200,000 homeless in the aftermath of the hurricane.[3] President Antonio Guzmán Fernández estimated the combination of agricultural, property, and industrial damage to amount to $1 billion.[11]

Neighboring Haiti experienced very little from David, due to the hurricane's weakened state upon moving through the country.[3]

Bahamas

[edit]While passing through the Bahamas, David brought 70–80 mph (110–130 km/h) winds to Andros Island as the eye crossed the archipelago. David, though still disorganized, produced heavy rainfall in the country peaking at 8 in (200 mm).[11] Strong wind gusts uprooted trees, and overall damage was minimal.[12]

United States

[edit]

David produced widespread damage across the United States amounting to $320 million. Prior to the hurricane's arrival, 400,000 people evacuated from coastal areas. In total, David directly killed five in the United States, and was responsible for ten indirect deaths.[3]

Florida

[edit]Upon making landfall, David brought a storm surge of only 2–4 ft (0.61–1.22 m), due to its lack of strengthening and the obtuse angle at which it hit.[3] In addition, David caused strong surf and moderate rainfall, amounting to a maximum of 8.92 in (227 mm) in Vero Beach.[11] Though it made landfall as a Category 2 storm, the strongest winds were localized, and the highest reported wind occurred in Fort Pierce, with 70 mph (110 km/h) sustained and 95 mph (153 km/h) gusts.[13] The hurricane spawned over 10 tornadoes while passing over the state, though none caused deaths or injuries.[14] Total damages in Florida amounted to $95 million.[7] Two journalists from the Brevard County-based newspaper TODAY, reporter Dick Baumbach and photographer Scott Maclay, experienced extremely high winds as they followed the hurricane's progress from South Florida to Cocoa.[15]

Because the hurricane remained near the coastline, David failed to cause extreme damage in Florida. At the height of the storm, up to 50,000 people in Broward and Miami-Dade County (then Dade County) lost electricity due to downed and damaged power lines. Storm surge and abnormally high tides caused significant erosion damage to State Road A1A in the vicinity of Sunrise Boulevard in Fort Lauderdale.[16] Four fatalities occurred in Broward County, two directly and two indirectly.[17] In Palm Beach County, sustained winds peaked at 58 mph (93 km/h) at the Palm Beach International Airport and wind gusts reached up to 92 mph (148 km/h) in Jupiter. Winds shattered windows in stores near the coast and caused some property damage, including blowing the frame off the Palm Beach Jai alai fronton in Mangonia Park and downing the 186-ft (57-m) WJNO AM radio tower in West Palm Beach into the Intracoastal Waterway.[7] Around 70,000 people in or near West Palm Beach lost electricity after falling trees downed around one-third of Florida Power & Light's main feeder lines.[18] Abnormally high tides damaged docks and piers,[7] while also flooding portions of South Ocean Boulevard between Lake Worth and Lantana. In Palm Beach, several boats moored in the Lake Worth Lagoon capsized.[18] Damage in the county totaled approximately $30 million, most of it incurred to crops.[7]

Farther north, the storm deroofed a few structures and flooded some buildings in the Treasure Coast, including the Stuart City Hall. A 450-ft (140-m) crane was snapped in two at the St. Lucie Nuclear Power Plant.[7] In Vero Beach, a tornado caused major damage to a restaurant and deroofed a condominium and apartment building.[19]: 3 Some clapboard-style homes in the county suffered major damage, especially in Gifford and other low income communities. Heavy rains inundated portions of State Road 60 with up to 4 ft (1.2 m) of water between Interstate 95 and Yeehaw Junction because the St. Johns River marsh had difficulty draining.[20] Two tornadoes in Brevard County caused damage. The first twister severely impacted or destroyed about 50 mobile homes and a condominium complex in Melbourne Beach and a shopping center in Palm Bay after crossing the Indian River. The shopping center alone sustained about $1.5 million in damage. Another tornado was spawned in Cocoa, damaging a few roofs.[19]: 3

Georgia

[edit]

Hurricane David made landfall in Georgia as a quickly weakening minimal hurricane, bringing a 3–5 ft (0.91–1.52 m) storm surge and heavy surf. Its inner core remained away from major cities, though Savannah recorded sustained winds of 58 mph (93 km/h) and wind gusts of 68 mph (109 km/h).[3] Although no major damage occurred in Savannah,[21] high winds downed numerous power lines, leaving approximately 70,000 electrical customers without power,[22]: 14 some for up to two weeks after the storm.[23] Many trees were downed along downtown streets.[24] Tybee Island and its vicinity may have experienced hurricane-force wind gusts.[22]: 14 Several homes on the island were partially deroofed.[24] In Darien, the storm severely damaged a nursing home, flooded some streets, and downed tree limbs.[25] Offshore, strong seas disrupted a portion of the coastal reef by moving a sunken ship 300 ft (91 m).[26] Tides produced by the storm also inundated the Jekyll Island Causeway and the F.J. Torras Causeway, which links Brunswick to St. Simons Island. Overall, David was responsible for approximately $5 million in damage in Georgia, much of it in Chatham County, while two people drowned at Jekyll Island due to heavy surf.[22]: 14

Southeast, Mid-Atlantic and New England

[edit]Upon entering South Carolina, David retained winds of up to hurricane force, though the highest recorded was 43 mph (69 km/h) sustained in Charleston and a 70 mph (110 km/h) wind gust in Hilton Head Island.[3] The storm spawned at least five tornadoes in the state, four of which caused damaged. The first such twister, spawned in Georgetown, demolished five beachfront homes and severely damaged eight other homes and a condominium complex. A tornado touched down in North Myrtle Beach destroyed a few roofs and caused damage to utilities. Minutes later, a second tornado in the city demolished some fishing piers, substantial damaged several dwellings and a motels, and ignited a few fires, which destroyed a condominium complex. A third tornado in North Myrtle Beach caused some degree of roof damage to about 80 percent of oceanfront homes in the Windy Hill Beach section of the city. The twister also demolished three piers and a motel. David caused approximately $10 million in damage in South Carolina.[19]: 10

Similar winds occurred in North Carolina, and lesser readings were recorded throughout the northeastern United States, excluding a 174 mph (280 km/h) wind gust on Mount Washington in New Hampshire. In addition, David dropped heavy rainfall along its path, peaking at 10.73 in (273 mm) in Cape Hatteras, North Carolina, with widespread reports of over 5 in (130 mm). Storm surge was moderate, peaking at 8.8 ft (2.7 m) in Charleston and up to 5 ft (1.5 m) along much of the eastern United States coastline.[3]

Overall, damage was light in most areas, though it was very widespread. High winds and rain downed power lines in the New York City area, leaving 2.5 million people without electricity during the storm's passage. Had David not taken an unexpected very late turn, it would have likely toppled the Citicorp Building (53rd and Lexington), which was in the process of being fortified because the building could not withstand hurricane-level winds; a major tragedy affecting a square mile of Midtown Manhattan (including Grand Central Station, the UN, and Rockefeller Center), was avoided.[3] David also caused minor to moderate beach erosion, as well as widespread crop damage from the flooding.[27] In addition, the hurricane spawned numerous tornadoes while moving through the Mid-Atlantic and New England, with associated prominent wind damage occurring even in inland communities.[28] In Virginia eight tornadoes formed across the southeastern portion of the state, of which six were F2's or greater on the Fujita scale, including two rated F3 in Fairfax County and Newport News. The tornadoes caused 1 death, 19 injuries, damaged 270 homes, and destroyed 3 homes, amounting to $6 million in damage. In Maryland, David's outer bands formed seven tornadoes,[29] including an F2 in Kingsville.[30] In New Castle County, Delaware, an F2 tornado damaged numerous homes and injured five.[31]

Aftermath

[edit]Dominica

[edit]Immediately after the storm, lack of power prevented communications and the outside world had little knowledge of the extent of the damage in Dominica. A citizen named Fred White ended that by using a battery-operated ham radio to contact the world.[5]

In response to the severe agricultural damage, the government initiated a food ration. By two months after the storm, assistance pledges amounted to over $37 million from various groups around the world. Similar to the aftermath of other natural disasters, the distribution of the aid raised concerns and accusations over the amount of food and material, or lack thereof, for the affected citizens.[5] The Hurricane destroyed some important landmarks, including a significant part of the ruins of the Fort Young which had stood since the 1770s.[32]

The looting was practiced in supermarkets, seaports, and homes; what was not destroyed by the hurricanes was stolen in the weeks after the storm.[6]

The destroyer HMS Fife (D20) was on its way back to the United Kingdom when the hurricane struck, and was turned back to provide emergency aid to the island. Sailing through mountainous seas, Fife docked in the main harbor at Roseau without assistance, and was the only outside help for several days. The crew provided work details and medical parties to offer assistance to the island and concentrated on the hospital buildings, the airstrip, and restoring power and water. The ship's helicopter (called Humphrey) took medical aid into the hills to assist people who were cut off from getting to other help by fallen trees. The ship also used its radio systems to broadcast news and music to the island to inform the population of what was being done and how to get assistance. This was the first time a Royal Navy ship had provided a public broadcast news service.[citation needed]

Dominican Republic

[edit]Immediately following the storm, more than 200,000 people left homeless sought refuge at churches and public buildings. Tropical Storm Frederic struck the Dominican Republic only about a week after David, exacerbating recovery efforts. In September 1979, the Civil Defense Secretariat of the Dominican Republic provided assistance to approximately 1.8 million people via international organizations such as Care International (CARE), the Catholic Relief Services (CRS), the Church World Service (CWS), and the Peace Corps. Prior to David, these organizations had staged over 16,500,000 lb (7,500,000 kg) of P.L. 480 food commodities, which suffered little damage from the storm. CARE and CRS distributed an additional 20,003,000 lb (9,073 t) of P.L. 480 food commodities between October 1979 and September 1980. The Civil Defense Secretariat also ordered nearly all privately owned construction equipment be used to clear blocked roadways. Approximately 500,000 sheets galvanized roofing, manufactured locally, was purchased by the government of the Dominican Republic. Within two months, the National Housing Institute and private firms repaired over 12,000 homes. The Secretariat of Agriculture provided assistance with replanting 60–90-day crops. Businesses, non-governmental organizations, and volunteers within the Dominican Republic also contributed significantly, providing construction materials and bedding, clothing, and shoes. Thousands of family-sized food parcels were packed by volunteered and shipped to devastated areas.[33]

The United Nations and intergovernmental organizations, including the European Economic Community, Food and Agriculture Organization, Inter-American Development Bank, Organization of American States, Pan American Health Organization, United Nations Development Programme, United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs, United Nations Children's Fund, World Food Programme, and World Bank, provided more than $139.2 million in material and monetary donations.[33]

Cash donations and relief supplies were contributed from Red Cross agencies throughout the world, including from Australia, the Bahamas, Belgium, Canada, Chile, Colombia, Denmark, Finland, Germany, Honduras, Hungary, Italy, Japan, Monaco, New Zealand, Norway, Romania, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, Thailand, the United Kingdom, the United States, and Yugoslavia. Additionally France's Médecins Sans Frontières and Action d'urgence internationale and the United Kingdom's Oxfam also provided money and supplies. Overall, contributions from these non-governmental organizations totaled nearly $203.13 million.[33]

The United States Congress and president Jimmy Carter approved legislation appropriating $15 million in aid to the Dominican Republic. By 1980, the United States government contributed funds and materials with a monetary value totaling just over $10.1 million. Aside from CARE, CRS, and CWS, non-governmental organizations based in the United States with significant donations of funds and supplies were the American Institute for Free Labor Development, Assemblies of God, Baptist World Alliance, Brother's Brother Foundation, Catholic Medical Mission Board, Compassion International, Direct Relief, Lutheran World Relief, MAP International, Michigan Partners of the Americas, Missionary Enterprises, Redemptorists (Baltimore Province), Roman Catholic Episcopate of Puerto Rico, Salesians of St. John Bosco, Salvation Army, Save the Children USA, Seventh-day Adventist World Service, Sister Cities International, Southern Baptist Convention, World Relief, and World Vision International. These organizations combined gave over $2.5 million in aid. Other national governments contributing aid included Argentina, Austria, Canada, Colombia, Cuba, El Salvador, France, Germany, Haiti, Japan, Liechtenstein, Netherlands, Norway, Sweden, Switzerland, Taiwan, the United Kingdom, and Venezuela.[33]

United States

[edit]Despite the casualties and damages attributed to David, the storm's effects were not as bad as in other countries. In particular, South Florida escaped relatively lightly. Because of this, then NHC Director Neil Frank was accused of overly stirring up panic before the arrival of David. Two local psychiatrists even claimed that the experience would make residents more complacent towards future storms. However, the NHC defended their methods, with Frank stating: "If we hadn't [raised public alarm] and our predictions had been more accurate, the consequences would have been disastrous."[7] One reporter who covered Hurricane David was Dick Baumbach, a journalist with TODAY newspaper, now known as Florida Today. He along with news photographer Scott Maclay followed the path of the hurricane from Miami to Central Florida. In Cocoa Beach, Baumbach decided to ride out the hurricane in his home with two other journalists. While it was a difficult and trying experience, all three reporters survived and ended up winning numerous awards.[15] The hurricane also interrupted the filming of the movie Caddyshack that was taking place at the Rolling Hills Country Club in Fort Lauderdale.[34]

Retirement

[edit]The name David was retired following this storm because of its devastation and high death toll; it will never be used again to name a tropical system in the North Atlantic.[35] It was replaced with Danny for the 1985 season.[36]

In popular culture

[edit]See also

[edit]- Other storms of the same name

- List of Category 5 Atlantic hurricanes

- List of retired Atlantic hurricane names

- Hurricane Matthew (2016) – Similar storm which took a similar track near the Southeastern United States

- Hurricane Irma (2017) – Another category 5 that affected the Caribbean

- Hurricane Maria (2017) – Another Category 5, regarded as the worst natural disaster on record to affect Dominica

References

[edit]- ^ Neely, Wayne (December 19, 2016). The Greatest and Deadliest Hurricanes of the Caribbean and the Americas: The Stories Behind the Great Storms of the North Atlantic. iUniverse. p. 375. ISBN 978-1-5320-1151-1. Retrieved August 9, 2018.

- ^ Hebert, Paul J. "Tropical Depression Advisory: August 25, 1979 2200 UTC". National Hurricane Center. United States National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration's National Weather Service. Retrieved October 3, 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w Hebert, Paul J (July 1, 1980). "Atlantic Hurricane Season of 1979" (PDF). Monthly Weather Review. 108 (7). American Meteorological Society: 973–990. Bibcode:1980MWRv..108..973H. doi:10.1175/1520-0493(1980)108<0973:AHSO>2.0.CO;2. Archived from the original (PDF) on January 4, 2011. Retrieved October 3, 2021.

- ^ "Atlantic hurricane best track (HURDAT version 2)" (Database). United States National Hurricane Center. April 5, 2023. Retrieved November 18, 2024.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ a b c d e f g Honeychurch, Lennox. "Scenes from Hurricane David on August 29, 1979". sakafete.com. Archived from the original on January 24, 2010. Retrieved October 3, 2021.

- ^ a b c d e Fontaine, Thomson (August 29, 2003). "Remembering Hurricane David". TheDominican.Net. Retrieved October 5, 2010.

- ^ a b c d e f g Kleinberg, Eliot (May 27, 2004). "David: A hit – and a miss". The Palm Beach Post. Archived from the original on February 16, 2009. Retrieved October 3, 2021.

- ^ a b Centre for Research on the Epidemiology of Disasters. "EM-DAT: The OFDA/CRED International Disaster Database". Université catholique de Louvain. Retrieved November 30, 2012.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Lawrence, Miles (October 17, 1979). "Meteorological Effects, Fatalities And Damages". Preliminary Report: Hurricane David – August 25-September 7, 1979 (Report). National Hurricane Center. p. 3. Retrieved October 3, 2021.

- ^ García, José M. "Hurricanes and Tropical Storms in Puerto Rico from 1900 to 1979". The Puerto Rico Hurricane Center. Retrieved October 3, 2021.

- ^ a b c d e Lawrence, Miles (October 17, 1979). "Meteorological Effects, Fatalities And Damages". Preliminary Report: Hurricane David – August 25-September 7, 1979 (Report). National Hurricane Center. p. 4. Retrieved October 3, 2021.

- ^ "Bahamas Hurricane History". Bahamas Department of Meteorology. Archived from the original on April 29, 2006. Retrieved October 3, 2021.

- ^ Lawrence, Miles (October 17, 1979). "Meteorological Data (U.S.) Hurricane David, Aug. 25–Sept. 7, 1979". Preliminary Report: Hurricane David – August 25-September 7, 1979 (Report). National Hurricane Center. p. 8. Retrieved October 3, 2021.

- ^ Hagemeyer, Barlett C. 1.2 Significant Tornado Events Associated With Tropical and Hybrid Cyclones in Florida (Report). National Weather Service Melbourne, Florida. Archived from the original on October 16, 2008. Retrieved October 3, 2021.

- ^ a b Baumbach, Dick (September 4, 1979). "Journey Through Nature's Fury". Florida Today. Cocoa, Florida. p. 1a. Retrieved October 3, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Casey, Dave (September 4, 1979). "David In Broward: 4 Persons Die, But Property Damage Is Minimal". Fort Lauderdale News. p. 5A. Retrieved October 4, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Casey, Dave (September 4, 1979). "4 Die In Broward; Property Damage Is Minimal". Fort Lauderdale News. p. 1A. Retrieved October 4, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b Keefer, Charles (September 4, 1979). "PB County's Damage Put At $1 Million". The Palm Beach Post. p. A19. Retrieved October 4, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b c "Storm Data and Unusual Weather Phenomena" (PDF). Storm Data. 21 (9). September 1979. ISSN 0039-1972. Archived from the original (PDF) on May 29, 2014. Retrieved October 6, 2021.

- ^ Miller, Gregory (September 5, 1979). "Area Clears Away $30 Million Damage". Florida Today. Cocoa, Florida. p. 16a. Retrieved October 5, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Savannah, Georgia's history with tropical systems". Hurricane City.com. Retrieved October 3, 2021.

- ^ a b c "Storm Data and Unusual Weather Phenomena" (PDF). Storm Data. 21 (10). October 1979. ISSN 0039-1972. Archived from the original (PDF) on October 6, 2021. Retrieved October 6, 2021.

- ^ Prokop, Patrick. "Savannah Hurricane History". WTOC TV. Archived from the original on February 26, 2006.

- ^ a b Morrison, David (September 6, 1979). "Busbee Tours Coastal Area, Pledges State Disaster Aid". The Atlanta Constitution. p. 10-A. Retrieved October 6, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Goolrick, Chester; Merriner, Jim (September 5, 1979). "Hurricane". The Atlanta Constitution. p. 8-A. Retrieved October 6, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Burke, John (June 14, 1998). "DNR hopes deep-water reef draws fish". The Savannah Morning News. Retrieved October 3, 2021.

- ^ Lawrence, Miles (October 17, 1979). "Meteorological Effects, Fatalities And Damages". Preliminary Report: Hurricane David – August 25-September 7, 1979 (Report). National Hurricane Center. p. 5. Retrieved October 3, 2021.

- ^ Cleeton, Christa (November 9, 2012). "Before Sandy, there was Gloria and David: Hurricane damage on campus". Princeton University Archives & Public Policy Papers Collection. Retrieved October 3, 2021.

- ^ Watson, Barbara (February 21, 2002). "Virginia Tornadoes". Archived from the original on September 4, 2005.

- ^ "Summary". TornadoHistoryProject.com. Archived from the original on October 28, 2018.

- ^ "The Most Important Tornadoes by State". TornadoHistoryProject.com. 2000. Archived from the original on March 4, 2016. Retrieved October 3, 2021.

- ^ Gravette, Andrew Gerald (2000). Architectural heritage of the Caribbean: an A-Z of historic buildings. Signal Books. p. 168. ISBN 978-1-902669-09-0. Retrieved June 22, 2011.

- ^ a b c d Dominican Republic – Hurricane David & Frederic (PDF). United States Agency for International Development; Office of Foreign Disaster Assistance (Report). Disaster Case Report. Washington, D.C.: United States Agency for International Development. Retrieved October 5, 2021.

- ^ Burke, Peter (July 25, 2020). "'Caddyshack' at 40: How South Florida set tee time for greatest golf satire in cinematic history". WPTV-TV. Retrieved October 3, 2021.

- ^ "Tropical Cyclone Naming History and Retired Names". Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved April 4, 2024.

- ^ National Hurricane Operations Plan (PDF) (Report). Washington, D.C.: NOAA Office of the Federal Coordinator for Meteorological Services and Supporting Research. May 1985. p. 3-7. Retrieved April 4, 2024.

- ^ Dicale, Bertrand (September 9, 2017). "Ces chansons qui font l'actu après le cyclone" [These songs that make the news after the cyclone] (in French). France TV Info. Retrieved October 3, 2021.

External links

[edit]- Radar loop of Hurricane David

- Satellite loop of David, Elena, Frederic, and Gloria

- Hurricane David Rainfall – HPC

- Hurricane David damage (archived 26 April 2006)

- Remembering Hurricane David

- CHC Storms 1979 (archived 10 February 2006)

- PalmBeachPost.com (Hurricane David)

- 1979 Atlantic hurricane season

- Cape Verde hurricanes

- Category 5 Atlantic hurricanes

- Retired Atlantic hurricanes

- Natural disasters in the Leeward Islands

- Natural disasters in Dominica

- Hurricanes in the Leeward Islands

- Hurricanes in Martinique

- Hurricanes in Dominica

- Hurricanes in Guadeloupe

- Hurricanes in Îles des Saintes

- Hurricanes in the United States Virgin Islands

- Hurricanes in Puerto Rico

- Hurricanes in the Dominican Republic

- Hurricanes in Haiti

- Hurricanes in the Bahamas

- Hurricanes in Florida

- Hurricanes in Georgia (U.S. state)

- 1979 in Dominica

- 1979 in the Dominican Republic

- 1979 natural disasters in the United States

- 1979 in the Caribbean