Baker Bowl

A 1928 aerial view of Baker Bowl with the soon-to-be-demolished Huntingdon Street station (at right) in Philadelphia | |

| |

| Former names | Philadelphia Baseball Grounds (1887–1895) National League Park (1895–1913, officially thereafter) |

|---|---|

| Location | 2622 N. Broad St./2601 N. 15th Street, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, U.S. |

| Coordinates | 39°59′35″N 75°9′21″W / 39.99306°N 75.15583°W |

| Public transit | Reading and Pennsylvania Railroad: Huntingdon Station (1891–1929), North Broad station (1929–1950) |

| Owner | Philadelphia Phillies |

| Operator | Philadelphia Phillies |

| Capacity | 12,500 (1887–94) 18,000 (1895–1928) 20,000 (1929) 18,800 (1930–38) |

| Field size | Left Field – 341 ft (104 m) Center Field – 408 ft (124 m) Right-Center – 300 ft (91 m) Right Field – 280 ft (85 m)  |

| Surface | Grass |

| Construction | |

| Opened | April 30, 1887 |

| Renovated | 1894-1895 |

| Closed | June 30, 1938 |

| Demolished | 1950 |

| Construction cost | US$80,000 ($2.71 million in 2023 dollars[1]) |

| Architect | John D. Allen |

| Tenants | |

| Philadelphia Phillies (NL) (1887–1938) Philadelphia Athletics (EL) (1892) Philadelphia Phillies (ALPF) (1894) Philadelphia Athletics (AtL) (1896–1900) Philadelphia Phillies (NFL) (1902) Philadelphia Eagles (NFL) (1933–35) La Salle Explorers (NCAA) (1931–36) | |

| Designated | August 16, 2000[2] |

National League Park, commonly referred to as the Baker Bowl after 1923, was a baseball stadium home to the Philadelphia Phillies from 1887 until 1938, and the first home field of the Philadelphia Eagles from 1933 to 1935. It opened in 1887 with a capacity of 12,500. It burned down in 1894 and was rebuilt in 1895 as the first ballpark constructed primarily of steel and brick and with a cantilevered upper deck.

The ballpark's first base line ran parallel to Huntingdon Street; right field to center field parallel to North Broad Street; center field to left field parallel to Lehigh Avenue; and the third base line parallel to 15th Street. The stadium was demolished in 1950.

History

[edit]1887 construction

[edit]

The Philadelphia Phillies had played at Recreation Park since their first season in 1883. Phillies owners Al Reach and John Rogers built the new National League Park for $80,000 with a capacity of 12,500[3] to open for the 1887 season.

Philadelphia's Building Inspectors' office issued a permit to Joseph Bird on August 4, 1886, to construct a pavilion 130 x 105 feet, one story high, at the northeast corner of Fifteenth and Huntingdon Streets. The pavilion was built of iron and brick and featured two turrets. The ballpark's superintendent would live in one of the turrets.[4]

The new ballpark was to have opened on April 4, 1887, for the preseason City Series against the Philadelphia Athletics, but inclement weather delayed final construction.[5]

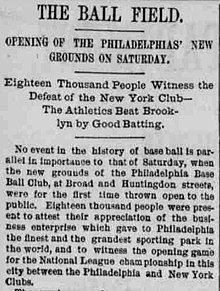

The Phillies played their first game in the new ballpark on Saturday, April 30, 1887, in the home opener against the New York Giants. 18,000 tickets were sold for the first game, with 13,000 in the stands. An additional 5,000 fans crowded onto the 1,320 ft (400 m) by 15 ft (4.6 m) wide bicycle track which encircled the field,[6][7] and others in the terraces above left field.

Philadelphia Mayor Edwin Henry Fitler attended along with the city's political and business leadership and many baseball leaders, including New York Giants owner John B. Day, Brooklyn Dodgers' founder and owner Charlie Byrne, Baltimore Orioles manager Billy Barnie, and Philadelphia Athletics manager Lew Simmons. The Phillies defeated New York 15 to 9.[8]

The original layout of the field was different from its shape by 1895. In 1887, the dimensions of the playing field were left field 425 ft (130 m), center field 330 ft (100 m), and right field 290 ft (88 m). The long left field distance was to the outer wall before the bleachers were added. The center field was much closer than it became later when the center field area was extended over the sunken railroad tracks.

The bicycle track was upgraded in October 1890. During the 1891 baseball season, the Phillies welcomed fans to ride their bicycles to games, check and lock their cycles at the park, and then use the bicycle track at the end of the game.[9]

Following the 1893 season, the Reading Railroad constructed a railroad tunnel under the intersection of Broad Street and Lehigh Avenue and the ballpark's centerfield, creating the ballpark's distinctive outfield "hump", and elevating the street level along the outfield fences. This tunnel continues to be used today by SEPTA Regional Rail's Main Line. To prevent fans from viewing the games over the right field wall along the now higher Broad Street, the Phillies constructed the 12-foot-high (3.7 m) fence before the 1894 season.[10]

1894 fire

[edit]On August 6, 1894, the grandstand and bleachers of the original stadium were destroyed in a fire, inflicting $80,000 in damages (equal to $2,817,231 today), which was covered fully by insurance. The fire also spread to the adjoining properties, causing an additional $20,000 in damage, equal to $704,308 today.[11]

While the Phillies were playing a short road trip and staging six home games at the University of Pennsylvania Grounds at 37th and Spruce, a building crew worked around the clock erecting temporary bleachers. The makeshift stands were finished in time for the game on August 18.

1895 reconstruction and expansion

[edit]

During the 1894–95 off-season, the park was fully rebuilt, seated 18,800, and was dedicated on May 2, 1895.

The Phillies' National League Park was the first ballpark to be constructed primarily of steel and brick to prevent future fires. The ballpark had outer brick walls on all four sides, three wide steel stairways between decks, and a series of fifteen 30-foot heavy iron girders supporting the platforms and roof of the upper deck. The upper deck was made possible by the use of the cantilever system.

Cantilever design was a new architectural technique in stadium construction in 1894, and National League Park was the first to be constructed with it. The ballpark's cantilevered concrete supports eliminated the need for many of the support columns in the pavilion that had made for “obstructed view seating” in the original ballpark and other stadiums. Use of the cantilever design would become, and continues to be standard in the construction of stadiums.[12]

The sweeping curve behind the plate was about 60 feet (18 m), and instead of angling back toward the foul lines, the 60-foot-wide (18 m) foul ground extended all the way to the wall in right, and well down the left field line. The spacious foul ground allowed for a higher probability of foul flyouts and extended an advantage to pitchers.

Seats were added along the left field wall prior to the 1896 season.[13]

The ballpark was held in such high regard that in April 1897, the Philadelphia Inquirer reported on Phillies' outfielder Sam Thompson singing the park's praises to the team's new players as they returned to Philadelphia from spring training, "...Thompson says that if he can see the cantilever just once more he will die happy. Many of the boys have never seen the monument at Broad and Huntingdon streets, and Samuel has given luminous descriptions of the hump, grade, and drainage system."[14]

Prior to the 1897 season, Phillies owner John Rogers claimed that the ballpark's capacity was 20,008.[15]

During the August 8, 1903 game against Boston with 10,078 in the stands, an altercation between two drunken men and two teenage girls on 15th Street caught the attention of bleacher fans down the left field line.[3] Many of the fans ran to the top of the wooden seating area, and the added stress on that section of the bleachers caused it to collapse into the street, killing 12 and injuring 232. This led to additional renovations to the stadium and forced ownership to sell the team.

The Phillies temporarily moved to the Philadelphia Athletics' home field, Columbia Park, while their ballpark was repaired.[16] The Phillies played sixteen games at Columbia Park in August and September 1903.[17]

The Phillies rebuilt the stands prior to the 1904 season, which had the effect of reducing capacity. Following the 1903 disaster, Phillies owner James Potter and the other club officers hosted National League president Harry Pulliam and the city's baseball writers for a luncheon, and then made an official tour of the ballpark to show off the reconstructed and reinforced left field bleachers.[18] The grandstand improvements were inspected by the City of Philadelphia's Chief Building Inspector and granted his approval.[19]

The Phillies' new ownership refurbished the ballpark further prior to the 1905 season. They had the grandstand painted and every seat cleaned. As they had the previous year before the season, the Phillies had the stands inspected by the chief of the city's Bureau of Building Inspections prior to Opening Day, and publicized his approval that they met all codes.[20]

The Phillies erected field-level seats extending from the left field stands around to the centerfield club house before the 1906 season, which increased capacity by 3,000 spectators. The ballpark had featured hanging seats in left field on Lehigh Avenue beneath which fans parked carriages, bicycles, and other vehicles; these accommodations were lost with the erection of the new left field stands.[21]

Prior to the 1907 season, a new corrugated roof was placed over half of the grandstand, and the visiting team clubhouse was refurbished with new showers and other amenities.[22] Through the 1907 season, the batters eye in centerfield was stonework and reflected the sun. Prior to the 1908 season, the Phillies' painted the stonework green to match the wood fences and reduce the glare; moved the score board to the right field foul line; and for the first time built covered dugouts described as "small pavilion-like sheds erected over the players' bench, completely shutting the bench out from view of the people in the grandstand."[23]

The park was refurbished again prior to the 1909 season with increased seating capacity, new box seats, and renovations to the players' clubhouse.[24] The park itself was painted green which the Philadelphia Inquirer welcomed as an improvement "instead of the old glaring assortment of rainbow colors which predominated in the past."[25] It was around this time that the double deck on the first base side was extended from the dugout all the way to the right field corner. This extension ran parallel to the foul line instead of curving, resulting in a relatively large amount of foul territory. This factor gave the right fielder more room to catch foul fly balls, theoretically mitigating the close proximity of the outfield wall to some extent.

During a game on May 14, 1927, parts of two sections of the lower deck extension along the right-field line collapsed due to rotted shoring timbers, again triggered by an oversize gathering of people, who were seeking shelter from the rain. While no one died during the collapse, one individual died of heart failure in the subsequent stampede that injured 50. As in 1903, the Phillies rented from the A's while repairs were being made to the old structure.

The left field stands and bleachers were entirely rebuilt with fresh lumber prior to the 1932 season.[26]

While the ballpark would never feature its own floodlights for night games, the House of David baseball team, traveling with portable arc lights, played a Philadelphia All-Star team featuring Grover Cleveland Alexander at night before 8,000 fans on July 25, 1932. Alexander had led the Phillies to the 1915 pennant at the ballpark and was cheered warmly when he came to bat.[27] The lights were placed on 50-foot-high poles around the playing field and powered by a portable 1000-watt generator with a 250-horsepower engine and radiator.[28]

A small incident occurred overnight on August 2–3, 1935, when a lightning bolt hit the flagpole and splintered it. The reporter wryly observed that if the Phillies were to win the 1935 pennant, they would have no place to hang it.[29] That was a safe proposition, as the Phillies finished in seventh place, 35+1⁄2 games behind the first-place Chicago Cubs.

When the Phillies departed in 1938, the ballpark did not offer motor vehicle parking, and would never feature a separate press box nor public address system. The stadium would never feature its own lights for night games.[30]

The Baker Wall

[edit]

National League Park was distinguished by its right field wall which at its closest distance was only 280 feet (85 m) from home plate, with right-center only 300 feet (91 m) away. Behind the right field wall was North Broad Street and North Broad Street train station across the street.

The right field wall came to be known as the Baker Wall after William Baker, who ran the club from 1913 until his death in 1930. The right field wall and fence in its final form was 60 feet (18 m) high. By comparison, Fenway Park's left field wall, the Green Monster, is 37 feet (11 m) high, and 310 feet (94 m) away.

The wall was an amalgam of different materials. It was originally a masonry structure topped by a wire fence.

With the advent of the live-ball era in 1920, it became significantly easier to hit home runs over the near right field wall. The Phillies extended the barrier upward with masonry, wood, and a metal pipe-and-wire fence. The lower part of the wall was rough[31] and eventually a layer of tin was laid over the entire structure except for the upper part of the fence.

Because of its material, it made a distinctive sound when balls ricocheted off it, as happened frequently. The clubhouse was located above and behind the center field wall.[3] No batter ever hit a ball over the clubhouse, but Rogers Hornsby once hit a ball through a window.[3]

1923 Baker Bowl naming

[edit]

The proper name of the original ballpark was Philadelphia Ball Park while the rebuilt structure from 1895 was National League Park.

The opening-day game program in 1887 called it Philadelphia Ball Park. Photographs during its later years show a sign on the ballpark's exterior reading National League Park. The Phillies referred to it as National League Park in newspaper advertisements through the final game day, June 30, 1938.

Huntingdon Street Grounds was an early common name for the ballpark after the street running behind the first base line and intersecting Broad Street behind home plate where the ballpark's primary entrance was located.

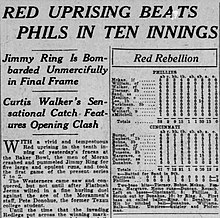

On July 11, 1923, The Philadelphia Inquirer coined the term Baker Bowl[32] after then Phillies owner William F. Baker. Baker had purchased the club in 1913 and would own the club until his death in 1930.

Built for the expectations of baseball in the dead ball era, it came to be seen as cramped and inadequate during the post-1920 live ball era. The ballpark was written about as "The Cigar Box" and "The Band Box", referring to the diminutive size of the outfield. After the close of the Baker Bowl, the terms "cigar box" and "bandbox" were subsequently applied to any "intimate" ballpark (like Boston's Fenway Park or Brooklyn's Ebbets Field) whose configurations were conducive to players hitting extra base hits and home runs.

The ballpark would also be referred to as "The Hump" in reference to the hill in center field covering the partially submerged railroad tunnel in the street beyond right field that extended through into center field. Outfielders would occasionally feel the rumblings of the trains passing underneath them.

Philadelphia Phillies

[edit]

During the 51+1⁄2 seasons the Phillies played there, they managed only one pennant, in 1915. The 1915 World Series was the first attended by a sitting US president, Woodrow Wilson,[33] and the last to be played in a venue whose structure predated the establishment of the post-season interleague championship.

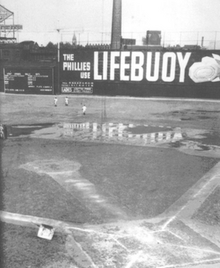

While the Phillies were occasionally at least respectable in the dead-ball era, once the lively ball was introduced the team became less competitive.[34] It was an extremely hitter-friendly park, making it an especially difficult place to pitch. For a number of years, a huge advertising sign on the right field wall read "The Phillies Use Lifebuoy", a popular brand of soap. This led to the oft-reported quip that appended "... and they still stink!" In 1936, a vandal snuck into the Baker Bowl one night and actually wrote that phrase on the Lifebuoy ad.[35] Conventional wisdom ties their failures to the Baker Bowl, but they often finished poorly in Shibe Park as well.

At the ballpark on September 17, 1900, in game 1 of a doubleheader against the Cincinnati Reds, the Phillies were discovered to have been stealing opponents' signs using hidden wires and an electronic device. Phillies’ backup catcher Morgan Murphy sat in the team's centerfield clubhouse window which faced home plate. The Phillies ran wires from Murphy, under the field, to a battery-powered device in a box buried underneath the third-base coach's box. From centerfield, Murphy would spot the opposing catcher's signals, and then send an electronic signal – once for a fastball and twice for a breaking ball. Phillies infielder Pearce Chiles coached third-base, received the signal beneath his feet, and signaled to the batter.

Cincinnati shortstop Tommy Corcoran had noted Chiles' unusual leg jolts. In the third inning, Corcoran walked to the third-base coach's box and began digging at the dirt with his cleats. Before the Phillies' groundskeeper could stop him, Corcoran had unearthed the electronic box and showed it to umpire Tim Hurst. Hurst disciplined no one, signaled the game to continue, and is reported to have shouted, "Back to the mines, men!"[36]

On June 9, 1914, Honus Wagner hit his 3,000th career hit in the stadium. Babe Ruth, then with the Boston Braves, played his final major league baseball game in the Baker Bowl on May 30, 1935, grounding out to first base in his only at bat but getting an assist by throwing a runner out at home plate on a relay play from left field.[37] He reitred, at 40, after a poor start, confident of receiving a managerial offer, but one never came from any franchise, only a brief stint as a 1st base coach three years later for the Brooklyn Dodgers.

When the ballpark first opened, it was praised as among the finest baseball palaces in America. Phillies' ownership under Colonel John Rogers invested in the grounds and made continuous improvements the 1890s, and the Phillies' owners in the early 1900s did the same. William Baker, the Phillies' owner from 1913 to 1930, neglected the ballpark's maintenance and allowed it to fall into disrepair. Baker died in 1930 in the early days of the Depression, and the Phillies new ownership were not in a position to make badly needed renovations.

The Chicago Tribune ran a series of articles on baseball parks during the summer of 1937; the article on the Phillies' ballpark was merciless in its ridicule.[38] Included was the oft-repeated joke of this era that the Phillies had remodeled the clubhouse by installing brand new nails to hang their clothes upon. This was in contrast to the 1890s when the same clubhouse was known for its handball court, pool, trainers' facilities, and locker room.

The ballpark was abandoned during the middle of the 1938 season, as the Phillies chose to move five blocks west on Lehigh Avenue to rent the newer and more spacious Shibe Park from the Athletics rather than remain at the Baker Bowl. Phillies president Gerald Nugent cited the move as an opportunity for the Phillies to cut expenses as stadium upkeep would be split between two clubs.[39] The final game was played on June 30, when a crowd of only 1,500 spectators watched the Phillies lose to the New York Giants, 14–1.[3]

At the Baker Bowl, the Phillies finished with a 30–38–1 record against the Athletics in City Series exhibition games.[40]

Philadelphia Eagles

[edit]Philadelphia Ball Park was the first home field of the Philadelphia Eagles, who played there from 1933 through 1935. In their three seasons there, they had a 9–21–1 record.

Eagles' owner Bert Bell hoped to play home games at larger Shibe Park, but negotiations with the Athletics were not fruitful, and Bell agreed to a deal with Phillies' owner Gerry Nugent. For Eagles games, 5,000 temporary seats were erected along the right-field wall. The Eagles played their first game at the ballpark on October 3, 1933, a 40–0 pre-season victory over a U.S. Marines team; the game was played at night under rented floodlights. In the first regular-season game on October 18, 1933, 1,750 fans saw the Portsmouth Spartans beat the Eagles, 25–0. Later that season, 17,850 fans watched the Eagles tie the Chicago Bears on Sunday, November 12, 1933. Under Pennsylvania blue laws, Sunday games had been prohibited.[41]

With the ballpark in poor condition, the Eagles left the ballpark after the 1935 season for the city-owned Municipal Stadium, which was then only 10 years old and could seat up to 100,000 spectators.

Other tenants

[edit]

In addition to Phillies baseball and Philadelphia Eagles football, the ballpark served the city as a multipurpose playing field available to other teams.

The ballpark was selected as a neutral host site for Game 6 of the 1888 World Series played on October 22, 1888. 4,000 fans saw the National League New York Giants defeat the American Association St. Louis Browns including veteran journalist Henry Chadwick, and popular entertainers DeWolf Hopper and Digby Bell.[42]

In 1894, six of the National League baseball clubs organized the American League of Professional Football Clubs, a professional soccer league. The league's inaugural game was played at Philadelphia Ball Park on October 6, 1894. The playing field measured 160 by 330 feet, and 500 fans saw New York defeat Philadelphia 5 to 0.[43]

The Cleveland Spiders played nine 'home games' at the ballpark on July 29–30, August 5–6, 8, and 11, 1898.[44]

The minor league baseball Tri-State League contested its 1904 championship game at the Phillies' ball park. York defeated Williamsport before 3,500 fans.[45]

Central High School's football team opened its season against Atlantic City High School on October 20, 1906, at the park.[46]

During its tenure, the park hosted Negro league games, including four postseason seasons. In 1921, the Chicago American Giants (champions of the Negro National League) played a series against the team considered the best of the East in the Hilldale Club. The Baker Bowl hosted the first two games of a best-of-six series that Hilldale won three (with one tie).[47]

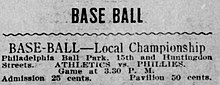

Three years later, the venue hosted the first two games of the 1924 Colored World Series between the Kansas City Monarchs and the Hilldale Club that the Monarchs won in ten games.[48] The following year, the two teams met again in the 1925 Colored World Series; the Baker Bowl hosted Game 5 and 6 in a series that saw Hilldale win their first and only World Series.[49] The following year, the Bowl hosted Game 4 and 5 of the 1926 Colored World Series.[50] It was during a 1929 exhibition with a Negro league team that Babe Ruth hit two home runs that landed about halfway into the rail yards across the street in right.[51]

In 1923, Phillies Park hosted multiple college football games of Saint Joseph's Hawks football.[52] LaSalle University opened its 1932 football season at the ballpark hosting Mount St. Mary's.[53]

Boxing matches were held at the ballpark and attracted large crowds. 35,000 spectators saw George Godfrey lose on a foul to Primo Carnera on June 23, 1930.[54]

1938 to 1950

[edit]

Among all Major League Baseball parks whose permanent structures were built in the 19th century, the Baker Bowl remained open the longest, hosting its last game on June 30, 1938, or about 51+1⁄2 years after it opened[55] and 43 years after it had burned and been completely rebuilt. (Robison Field in St. Louis, the next-longest-lasting 19th-century big-league ballpark, had closed in 1920.)

As early as 1928, the ballpark's site was put forth by the Greater Kensington Business Men's Association as an advantageous location for the city's proposed convention center. The ballpark was across the street from the Reading Railroad's North Broad station and the city's Broad Street Line subway had recently opened.[56] The Philadelphia Convention Hall and Civic Center would be built in 1931 near the University of Pennsylvania and Philadelphia's Center City.

After the Phillies moved to Shibe Park, its new owners renamed the lot Philadelphia Gardens and experimented with various types of events. For 1939 the roof and upper deck were peeled off and a midget-car race track was built around the inside perimeter.

In the summer of 1940, an ice rink of regulation hockey dimensions was installed, its underground machinery maintaining a frozen surface and enabling ice skating year round.

The old centerfield clubhouse was remodeled into a piano bar and entertainment venue called "Dick McClain's Alpine Musical Bar" which opened on May 15, 1942, with the Harlem Highlanders.[57][58] It would remain open until sometime in the summer of 1943.

Temple's hockey team played some of their games at this site also.

In February 1946, Leonard Peto, owner of the former-Montreal Maroons NHL franchise, announced plans to revive the franchise in Philadelphia for the 1946-1947 NHL season as the league's seventh team. By March 1946, Peto and his partners had identified the Phillies' park site for their planned 20,000 uptown arena.[59] However, the group was unable to secure funding for the project and the arena was never built. Philadelphia would eventually receive an NHL expansion team in 1967.

By 1947, a business called Phillies Auto Mart at Broad and Huntington Streets advertised in the newspaper that prospective buyers could "Try It Out On the Old PHILLIES Ballpark Racing Oval."[60]

On July 11, 1950, one of the still standing structures at the southwest corner of Broad St and Lehigh Ave, repurposed into a bar and taproom, caught fire, and burned the 80-foot-long wooden structure to the ground. What was left of the ballpark was demolished afterwards.[61]

Legacy

[edit]

A Pennsylvania Historical marker stands on North Broad Street just north of West Huntingdon Street in Philadelphia. The marker is titled, "Baker Bowl National League Park" and the text reads,

The Phillies' baseball park from its opening in 1887 until 1938. Rebuilt 1895; hailed as nation's finest stadium. Site of first World Series attended by U.S. President, 1915; Negro League World Series, 1924-26; Babe Ruth's last major league game, 1935. Razed 1950.[62]

The marker was dedicated on August 16, 2000, at Veterans Stadium during an on-the-field pre-game ceremony. The marker was unveiled by former Phillies shortstop Bobby Stevens, who played for the team in 1931, and then–current Phillies pitcher Randy Wolf. The marker was displayed at the Vet through the end of the 2000 season and then moved to the location of the ballpark, just behind where the right field foul pole would be.[63]

Some distinctive buildings visible in vintage photos of the ballpark remain standing and help to mark the ballpark's former location. The most prominent structure is the 10-story-tall, triangular building across Lehigh to the north-northeast, behind what was centerfield. It was originally a Ford Motor Company building, and was constructed during the 1914 season. Another is the neoclassical North Broad Street Station train depot building across Broad Street from what was the end of the first base grandstand, and where Huntingdon tees into Broad. It opened in 1929 and is visible in later aerial photos of the ballpark. The building itself now houses a homeless shelter.

The active and in-use North Broad station serving SEPTA Regional Rail's Lansdale/Doylestown Line and Manayunk/Norristown Line stands behind the former station building.

The ballpark's site now features a gas station and convenience store where the center-field clubhouse once stood, garages, and a car wash.

Gallery

[edit]-

Philadelphia Ball Park upon its opening in 1887

-

Sketch of the ballpark's interior when it opened

-

Aftermath of the 1894 fire

-

Ed Delahanty BP 1899

-

The umpires lined up before a game of the 1915 World Series at Baker Bowl

References

[edit]- ^ 1634–1699: McCusker, J. J. (1997). How Much Is That in Real Money? A Historical Price Index for Use as a Deflator of Money Values in the Economy of the United States: Addenda et Corrigenda (PDF). American Antiquarian Society. 1700–1799: McCusker, J. J. (1992). How Much Is That in Real Money? A Historical Price Index for Use as a Deflator of Money Values in the Economy of the United States (PDF). American Antiquarian Society. 1800–present: Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis. "Consumer Price Index (estimate) 1800–". Retrieved February 29, 2024.

- ^ "PHMC Historical Markers Search". Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission. Commonwealth of Pennsylvania. Archived from the original (Searchable database) on 2013-11-13. Retrieved 2015-06-18.

- ^ a b c d e Jordan, David (2010). Closing 'Em Down: Final Games at Thirteen Classic Ballparks. USA: McFarland Publishing Company. p. 216. ISBN 9780786449682.

- ^ "Sport of All Sorts: More About the Phillies' Grounds". Philadelphia Inquirer. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. March 27, 1889. p. 6.

- ^ "Base Ball News: Philadelphia Club Grounds - News from the South". Philadelphia Inquirer. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. March 24, 1887. p. 3.

- ^ "Record of Sports: Events of Yesterday That Interest Sportsmen". Philadelphia Inquirer. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. April 2, 1887. p. 3.

- ^ Philadelphia Times. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. May 1, 1887. p. 1.

{{cite news}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ "The Ball Field: Opening of the Philadelphia's new grounds on Saturday". Philadelphia Inquirer. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. May 2, 1887. p. 3.

- ^ "Notes of the Diamond Field". Philadelphia Inquirer. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. March 15, 1891. p. 3.

- ^ "Comment About Various Sports: Manager Irwin Has Given Orders for the Phillies to Report to Duty". Philadelphia Inquirer. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. March 18, 1894. p. 24.

- ^ "Another Baseball Park Fire". The Christian Recorder. August 9, 1894.

- ^ "A Historical Sketch of Baker Bowl". philadelphiaathletics.org. Philadelphia Athletics Historical Society. January 22, 2019. Retrieved July 4, 2022.

- ^ "Passed Balls". Philadelphia Inquirer. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. April 14, 1896. p. 5.

- ^ "Phillies Might As Well Come Home". Philadelphia Inquirer. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. April 3, 1897. p. 4.

- ^ "Passed Balls". Philadelphia Inquirer. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. April 13, 1897. p. 4.

- ^ Macht, Norman L.; Mack, III, Connie (2007). Connie Mack and the Early Years of Baseball. University of Nebraska Press. p. 316. ISBN 978-0-8032-3263-1. Retrieved May 22, 2009.

- ^ "Alternate Site Games Since 1901". Retrosheet. Retrieved May 22, 2009.

- ^ "President Pulliam Views Phillies' Grounds". Philadelphia Inquirer. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. March 31, 1904. p. 10.

- ^ "Phillies' Bleachers O.K.". Philadelphia Inquirer. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. April 1, 1904. p. 10.

- ^ "Phillies-Athletics; Opening Game at the National's Ground Will Be Played Today". Philadelphia Inquirer. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. April 3, 1905. p. 10.

- ^ "Seating Capacity At Phillies Increased". Philadelphia Inquirer. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. April 5, 1906. p. 10.

- ^ "Phillies Meet Altoona Today". Philadelphia Inquirer. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. March 29, 1907. p. 10.

- ^ "Athletics Land the First Game, Score 5-0". Philadelphia Inquirer. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. April 7, 1908. p. 10.

- ^ "Phillies Home Tired, But Happy". Philadelphia Inquirer. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. March 31, 1909. p. 10.

- ^ "Baseball Takes Command Today". Philadelphia Inquirer. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. April 2, 1909. p. 10.

- ^ "City Series Pick-Ups". Philadelphia Inquirer. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. April 5, 1932. p. 14.

- ^ Baumgartner, Stan (July 26, 1932). "Alexander Hurls Well As Whiskers Beat All-Stars". Philadelphia Inquirer. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. p. 14.

As a spectacle the game was a distinct success. The lighting was excellent and the fans had no trouble at all in following the ball, even flies that were hit high in the air.

- ^ "Alexander's Squad Plays All-Phila. Foe". Philadelphia Inquirer. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. July 25, 1932. p. 9.

- ^ Philadelphia Inquirer, Aug. 3, 1935, p.11

- ^ "THE BALLPARKS: Baker Bowl, PHILADELPHIA, PENNSYLVANIA". thisgreatgame.com. This Great Game. 2022. Retrieved July 4, 2022.

- ^ Benson, Michael. Ballparks of North America. McFarland, 1989, p298.

- ^ "Red Uprising Beats Phillies In Ten Innings". Philadelphia Inquirer. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. July 11, 1923. p. 20.

- ^ Gordon, Robert (2005). Legends of the Philadelphia Phillies. Sports Publishing LLC. p. 3. ISBN 1-56639-454-6. Retrieved June 3, 2009.

- ^ Antonen, Mel (July 16, 2007). "Phillies Are No. 1 in Loss Column". USA Today. Retrieved April 1, 2009.

- ^ Shields, Gerard (February 28, 2010). "Hope is eternal, even for Phillies fans". The Philadelphia Inquirer. Retrieved August 22, 2010.

- ^ Fitzpatrick, Frank (January 24, 2020). "The Phillies were accused of using technology to steal signs 117 years before the Astros". Philadelphia Inquirer. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. Retrieved January 24, 2020.

- ^ "Philadelphia Phillies 11, Boston Braves 6 (1)". Retrosheet. Retrieved 14 November 2021.

- ^ Baker Bowl / Philadelphia Park (aka Philadelphia Grounds)

- ^ "Phillies Set to Close Deal for Use of Shibe Park". The New York Times. The Associated Press. June 26, 1938. p. 66. Retrieved July 3, 2021.

- ^ Westcott, Rich (1996). Philadelphia's Old Ballparks. Temple University Press. p. 51. ISBN 1-56639-454-6. Retrieved June 2, 2009.

- ^ Didinger, Ray; Lyons, Robert S. (2005). The Eagles Encyclopedia. Temple University Press. p. 199. ISBN 1-59213-449-1. Retrieved May 27, 2009.

- ^ "New York Wins, The Giants Achieve Their Fifth Victory Over the Association Champs". Philadelphia Inqurier. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. October 23, 1888. p. 3.

- ^ "New York Takes One: Inaugural Game of American Football League". Philadelphia Inquirer. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. October 7, 1894. p. 3.

- ^ Lowry, Philip J. (2006). Green Cathedrals. New York, New York: Walker & Company. p. 173. ISBN 0-8027-1608-3.

- ^ "Penn Park Wins the $1000 Game, Defeating Williamsport Easily By The Score Of 8 To 2". Philadelphia Inquirer. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. October 11, 1904. p. 10.

- ^ "C.H.S. to Play Atlantic Tomorrow". Philadelphia Inquirer. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. October 19, 1906. p. 10.

- ^ "1921 Championship Series".

- ^ "1924 Negro League World Series".

- ^ "1925 Negro League Postseason".

- ^ "1926 Negro League World Series".

- ^ Jenkinson, Bill (2007). The Year Babe Ruth Hit 104 Home Runs: Recrowning Baseball's Greatest Slugger. Carroll & Graf. ISBN 978-0-7867-1906-8.

- ^ "SATURDAYS COLLEGE". newspapers.com. Wilkes-Barre, Pennsylvania: Wilkes-Barre Times Leader. 13 October 1923. p. 10. Retrieved 13 February 2018.

- ^ "La Salle Will Tangle With Mt. St. Mary's at Phillies' Ball Park... La Salle in Opener". Philadelphia Inquirer. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. September 24, 1932. p. 20.

- ^ "Godfrey Loses to Carnera on Foul in Fifth: 35,000 See Giant Italian Triumph When Struck Low by Negro at Phillies' Park". The Philadelphia Inquirer. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. June 24, 1930. p. 1.

- ^ Boxscore

- ^ "Phillies' Ball Park Urged for Convention Hall". Philadelphia Inquirer. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. April 10, 1928.

- ^ Burlingame, Rudoph (May 15, 1942). "Club to Open Tonight at Broad, Lehigh". Philadelphia Inquirer. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. p. 14.

- ^ Burlingame, Rudoph (June 5, 1942). "Night Clubs List Stellar Attractions". Philadelphia Inquirer. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. p. 14.

- ^ "Peto Sure He Can Build Arena in Time; National Hockey League Weighs Club Here". The Philadelphia Inquirer. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. March 31, 1946. p. 31.

- ^ "Used Automobiles". The Philadelphia Inquirer. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. March 16, 1947. p. W15.

- ^ "Fire Razes Vacant Building at Old Phillies Ball Park". The Philadelphia Inquirer. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. July 12, 1950. p. 31.

- ^ "Baker Bowl National League Park". Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission. Archived from the original on May 12, 2005. Retrieved June 2, 2009.

- ^ Warrington, Bob. "Baker Bowl Honored with Historical Marker at Dedication Ceremony!". Philadelphia Athletics Historical Society. Archived from the original on September 8, 2008. Retrieved June 2, 2009.

External links

[edit]- Ballparks.com: Baker Bowl

- Ballparks of Baseball: Baker Bowl

- Clem's Baseball: Baker Bowl

- Philadelphia Athletics Historical Society: Baker Bowl

- Society for American Baseball Research: Baker Bowl

- 1921 Sanborn map showing the ballpark

- 1951 Sanborn map showing some remnants of the ballpark

| Events and tenants | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by | Home of the Philadelphia Phillies 1887–1938 |

Succeeded by |

| Preceded by first stadium

|

Home of the Philadelphia Eagles 1933–1935 |

Succeeded by |

- 1887 establishments in Pennsylvania

- 1938 disestablishments in Pennsylvania

- American football venues in Pennsylvania

- Baseball venues in Pennsylvania

- Broad Street (Philadelphia)

- Demolished sports venues in Pennsylvania

- Defunct college baseball venues in the United States

- Defunct Major League Baseball venues

- Defunct National Football League venues

- Defunct sports venues in Philadelphia

- Demolished buildings and structures in Pennsylvania

- History of Philadelphia

- Jewel Box parks

- La Salle Explorers football

- National Football League (1902) venues

- Philadelphia Eagles stadiums

- Philadelphia Phillies stadiums

- Saint Joseph's Hawks baseball

- Sports venues completed in 1887