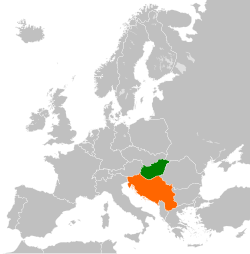

Hungary–Yugoslavia relations

Hungary |

Yugoslavia |

|---|---|

Hungary |

Yugoslavia |

|---|---|

| |

Hungary |

Yugoslavia |

|---|---|

Hungary |

Yugoslavia |

|---|---|

Hungary–Yugoslavia relations (Hungarian: Magyarország-Jugoszlávia kapcsolatok; Serbo-Croatian: Odnosi Mađarske i Jugoslavije, Односи Мађарске и Југославије; Slovene: Madžarsko-jugoslovanski odnosi; Macedonian: Односите меѓу Унгарија и Југославија) were historical foreign relations between neighboring Hungary (historically Kingdom of Hungary 1920-1946 and the Hungarian People's Republic 1949–1989) and now broken up Yugoslavia (Kingdom of Yugoslavia 1918-1941 and Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia 1945–1992).

Country comparison

[edit]| Common name | Hungary | Yugoslavia |

|---|---|---|

| Official name | Hungarian People’s Republic | Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia |

| Coat of arms |  |

|

| Flag |  |

|

| Capital | Budapest | Belgrade |

| Largest city | Budapest | Belgrade |

| Government | Unitary Marxist–Leninist one-party socialist republic | Socialist republic |

| Population | 10,375,323 | 22,229,846 |

| Official languages | Hungarian | No official language

Serbo-Croatian (de facto state-wide) Slovene (in Slovenia) and Macedonian (in Macedonia) |

| First leader | Mátiás Rakosi | Joseph Broz Tito |

| Last Leader | Rezsó Nyers | Milan Penčevski |

| Religion | Secular state (de jure), state atheism (de facto), Catholic (majority) | Secular state (de jure), state atheism (de facto) |

| Alliances | Warsaw Pact, Comecon | Non-Aligned Movement |

History

[edit]Interwar period

[edit]

At the time of creation of Yugoslavia during the Paris Peace Conference following the conclusion of World War I, the Entente Powers signed the Treaty of Trianon with Hungary after the breakup of Austria-Hungary. Among other things, the treaty defined the border between Hungary and the newly created Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes (renamed the Kingdom of Yugoslavia in 1929). Sizable numbers of Hungarians and Volksdeutsche remained in the areas incorporated into the kingdom. The newly formed Kingdom of Yugoslavia was a status quo state which sought to consolidate success of the South Slavic unification movement while Hungary was revisionist state whose leaders believed that their country had a right to some parts of Yugoslavia.

On 14 March 1941 in Budapest Foreign Ministers Aleksandar Cincar-Marković and László Bárdossy signed the Treaty of Eternal Friendship between Yugoslavia and Hungary. Following the short-lasting Yugoslav accession to the Tripartite Pact on 25 March 1941 the Yugoslav coup d'état took place on 27 March 1941 when the regency led by Prince Paul of Yugoslavia was overthrown and King Peter II fully assumed power. The coup led directly to the German-led Axis invasion of Yugoslavia in which Pál Teleki government of Hungary was pressured to join the attack. When Teleki received a call that is thought to have informed him that the German army had just started its march into Hungary.[1] Teleki committed suicide with a pistol during the night of 3 April 1941 and was found the next morning. His suicide note said in part:

We broke our word, – out of cowardice [...] The nation feels it, and we have thrown away its honor. We have allied ourselves to scoundrels [...] We will become body-snatchers! A nation of trash. I did not hold you back. I am guilty"[2][3]

Winston Churchill later wrote, "His suicide was a sacrifice to absolve himself and his people from guilt in the German attack on Yugoslavia."[4] On 6 April 1941, Germany launched Operation Punishment (Unternehmen Strafgericht), the bombing of Belgrade, Yugoslavia. Some historians consider Teleki's suicide an act of patriotism.[5] Britain shortly afterward broke diplomatic relations with Hungary but did not declare war until December.

World War II

[edit]During the World War II in Yugoslavia, Hungarian occupation of Yugoslav territories included military occupation, then annexation, of the Bačka, Baranja, Međimurje and Prekmurje regions of the Kingdom of Yugoslavia.

Cold War

[edit]After the end of the World War II relations between the two states rapidly improved but this development was abruptly interrupted by the escalation of the Soviet–Yugoslav conflict following the 1948 Tito-Stalin split.[6] Tensions eased in 1953 after Stalin's death.[6]

Hungarian Revolution of 1956

[edit]During 1956, Tito and Khrushchev met four times. While Yugoslav media and authorities verbally supported the Imre Nagy, Yugoslav authorities were nevertheless highly worried about nationalist rhetoric spillover into multiethnic Yugoslavia.[7] Between 31 October and 1 November, just three days before Soviet intervention, leading Yugoslav newspaper Borba stopped supporting Nagy government due to its "right-wing elements".[7] Yugoslav approach towards changes in Hungary was faced fear of Moscow’s wish to bring Yugoslavia back into its camp (which motivated Yugoslav support to Hungary) and fear of how rebellions could sweep away communist regimes (which motivated support to Soviet Union).[8] Nikita Khrushchev was therefore surprised with increasing Yugoslav willingness to agree with Soviet intervention as the Hungarian Revolution of 1956 progressed.[7] The Soviet Union launched a massive military invasion of Hungary on 4 November, forcibly deposing Nagy, who fled to the Embassy of Yugoslavia in Budapest where he was granted asylum. Nagy was lured out of the Embassy (after the building itself was targeted by Soviet tanks in which cultural attaché Milenko Milovanov was killed[7]) under false promises on 22 November, but was arrested and deported to Romania.

Hungarian community in Yugoslavia (particularly Hungarians in Vojvodina) played important role in preservation of Hungarian cultural pluralism in the years following the Soviet intervention. Novi Sad based journal Új Symposion, newspaper Magyar Szó and other media and institutions provided platform for authors to express diverse ideas and opinions.

“Quadrangolare”, the regional cooperation of Austria, Italy, Yugoslavia and Hungary was launched in 1988 as an effort to overcome the constraints presented by Cold War blocs.[9]

Breakup of Yugoslavia

[edit]Hungarian authorities sympathized with decentralization initiatives in Yugoslavia but were concerned over the prospect for Hungarians in Serbia in an independent Socialist Republic of Serbia under communist-nationalist leadership.[9]

See also

[edit]- Austro-Hungarian occupation of Serbia

- Croatia–Hungary relations

- Hungary–Kosovo relations

- Hungary–Serbia relations

- Group of Nine

References

[edit]- ^ Montgomery, John F. (1947). Hungary, the Unwilling Satellite. Simon Publications. ISBN 1-931313-57-1.

- ^ Horthy, Miklós; Andrew L. Simon (1957). "The Annotated Memoirs of Admiral Milklós Horthy, Regent of Hungary". Ilona Bowden. Archived from the original on 4 January 2010. Retrieved 6 July 2012.

- ^ Dimitrije Boarov (2011). Svetlana Lukić; Svetlana Vuković (eds.). Debele knjige i debele mačke. Čigoja štampa. p. 48. ISBN 978-86-86391-26-1.

- ^ Churchill, Winston; Keegan, John (1948). The Second World War (Six Volume Boxed Set). Mariner Books. pp. 148. ISBN 978-0-395-41685-3.

- ^ Sonya Yee (27 March 2004). "In Hungary, a Belated Holocaust Memorial". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on 20 May 2011. Retrieved 22 September 2009.

- ^ a b Vukman, Péter (2020). "Living in the Vicinity of the Yugoslav–Hungarian Border (1945–1960): Breaks and Continuities. A Case Study of Hercegszántó (Santovo)". History in Flux: Journal of the Department of History, Faculty of Humanities, Juraj Dobrila University of Pula. 2 (2): 9–27. Retrieved 15 February 2021.

- ^ a b c d Granville, Johanna (1998). "Hungary, 1956: The Yugoslav Connection". Europe-Asia Studies. 50 (3): 493–517. Retrieved 15 February 2021.

- ^ Tvrtko Jakovina. "Yugoslavia on the International Scene: The Active Coexistence of Non-Aligned Yugoslavia". YU historija. Retrieved 15 February 2021.

- ^ a b Jeszenszky, Géza. "Hungary and the Break-up of Yugoslavia - a Documentary History - Part I". Magyar Szemle. Retrieved 15 February 2021.

Further reading

[edit]- Hornyák, Árpád, and Thomas J. DeKornfeld. Hungarian-Yugoslav Diplomatic Relations 1918-1927 (Social Science Monographs, 2013), ISBN 9780880337014

.