Hungarian–Ottoman War (1366–1367)

| Hungarian-Ottoman War (1366-1367) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Ottoman-Hungarian wars Savoyard crusade | |||||||

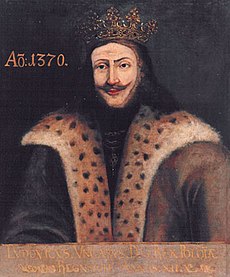

Louis the Great | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| Unknown | Unknown | ||||||

The Hungarian–Ottoman War (1366–1367) was the first confrontation between the Kingdom of Hungary and the Ottoman Empire in the Balkans. The war ended with a Hungarian victory, as Louis I's armies defeated the Ottomans in a battle near Nicopolis, although the outcome of the battle is still questioned by Turkish sources.

Background

[edit]In 1344, Louis I of Hungary, who would rule Hungary from 1342–1382 and earn the epithet "the Great", invaded Wallachia and Moldavia and established a system of vassalage.[1] Louis and his 80,000 strong army repelled the Serbian Dušan's armies in the duchies of Mačva and principality of Travunia in 1349. When Emperor Dušan broke into Bosnian territory he was defeated by Stjepan II with the assistance of Louis' troops, and when Dušan made a second attempt he was defeated by Louis in 1354. The two monarchs signed a peace agreement in 1355.[2]

His latter campaigns in the Balkans were aimed not so much at conquest and subjugation as at drawing the Serbs, Bosnians, Wallachians and Bulgarians into the fold of the Roman Catholic faith and at forming a united front against the Turks, which was also supported by the Pope in Avignon. It was relatively easy to subdue the Balkan Orthodox countries by arms, but to convert them was a different matter. Louis first led campaigns against the Bogumils in Bosnia and then he wanted to convert the Orthodox population, which deeply offended the Patriarch in Constantinople. But Byzantium was not in a position to engage in a conflict with Hungary. Despite Louis' efforts, the peoples of the Balkans remained faithful to the Eastern Orthodox Church and their attitude toward Hungary remained ambiguous. Louis annexed Moldavia in 1352 and established a vassal principality there, before conquering Vidin in 1365. The rulers of Serbia, Wallachia, Moldavia, and Bulgaria became his vassals. They regarded powerful Hungary as a potential menace to their national identity.[citation needed]

In Kraków Louis negotiated with Casimir III of Poland, at the congress, Casimir confirmed Louis's right to succeed him in Poland if he died without a male issue.

Louis assembled his armies in Temesvár in February 1365. According to a royal charter, he was planning to invade Wallachia because the new voivode, Vladislav I, had refused to obey him. However, he ended up heading a campaign against the Bulgarian Tsardom of Vidin and its ruler Ivan Sratsimir, which suggests that Vladislav had in the meantime yielded to him.[3] Louis seized Vidin and imprisoned Ivan Stratsimir in May or June. Within three months, his troops occupied Ivan Stratsimir's realm, which was organized into a separate border province, or banate, under the command of Hungarian lords.[citation needed]

The Byzantine Emperor, John V Palaiologos visited Louis in Buda in early 1366, seeking his assistance against the Ottoman Turks, who had set foot in Europe.[4] This was the first occasion that a Byzantine Emperor left his empire to plead for a foreign monarch's assistance.[5] On his way home, Emperor John was captured by Tsar Ivan Shisman. Upon learning of this incident, Louis decided to act independently and prepared for a campaign.[citation needed]

Louis sent another message to the Pope in Avignon to persuade him to declare the crusade. The Pope and cardinals, upon learning of John's capture, were no longer reluctant and supported the plan of the campaign.[citation needed]

War

[edit]Louis invaded Bulgaria.[6] Due to lack of data, it is not known exactly when and how he collided with the Turks. The clash most likely occurred near Nicopolis where Louis defeated the Ottoman army, however, Turkish sources do not confirm this. According to the volume entitled Hungarian military history written by Ervin Liptai, the Hungarian victory is confirmed by the survival of the Vidin province.[6]

In August, Amadeus VI landed in Gallipoli and captured the city. Here he met with the Patriarch of Constantinople, who reported that Ivan Shishman was still refusing to release John. Nevertheless, Amadeus continued the fight. The crusaders captured Varna, and from there the prince sent an embassy from the city's inhabitants to Ivan Shishman to free the emperor. The tsar was only willing to do so in exchange for the prince's cessation of the war. Amadeus agreed, and Ivan Shishman released John.[citation needed]

In this campaign, the Hungarians did not unite with the crusaders. In turn, Louis on 30 September and 5 March 1367 negotiated with the Venetians for two galleys, with which he was again preparing for war against the Turks. On December 6, 1366, the envoys of Doge Marco Cornaro visited his palace in Vértes and also discussed a possible Hungarian-Venetian anti-Ottoman alliance. The Bosnian king Tvrtko I recognized Louis as his lord, whom he successfully resisted in 1363, but had to seek protection due to Turkish attacks.[citation needed]

In 1367, Louis went on another campaign into Bulgaria, probably fighting the Turks at that time. Francesco Carrara, lord of Padua, sent 300 infantry from Senj to Louis that took part in this war. In addition to fighting against the Turks, Louis probably continued to convert the Balkan Slavs.[citation needed]

Aftermath

[edit]Louis continued to fight against the Bulgarian Empire between 1368 and 1369. Forced proselytization continued in the province of Vidin, which intensified the rebellion of the Bulgarian population. With Vidin, Louis tried to hold on to Wallachia, whose prince was the brother-in-law of Bulgarian tsar Vladislav Ivan Sratsimir. On the other hand, Vladislav increased his influence in the region, and when Louis returned Vidin to Ivan Sratsimir as a fief and entrusted Banate of Severin to Vladislav, Ivan Sratsimir joined forces with the Wallachians and rejected Hungarian rule.[citation needed]

It became clear that Louis no longer had sufficient forces to resolve the Bulgarian and Wallachian issues, which led to the growth of Turkish influence in Wallachia. The Bulgarians, who won against the Hungarians, were in fact the biggest losers of these wars, as their castles and lands were gradually occupied by the Turks, and by the 15th century the country was already part of the Ottoman empire.[citation needed]

See also

[edit]- Louis the Great

- Ivan Shishman

- Ottoman-Hungarian wars

- Hungarian-Ottoman War (1375-1377)

- John V Palaiologos

References

[edit]- ^ Ion Grumeza: The Roots of Balkanization: Eastern Europe C.E. 500-1500, University Press of America, 2010 [1]

- ^ Ludwig, Ernest. "Austria-Hungary and the war". New York, J. S. Ogilvie publishing company – via Internet Archive.

- ^ Божилов, Иван (1994). "Иван Срацимир, цар във Видин (1352–1353 — 1396)". Фамилията на Асеневци (1186–1460). Генеалогия и просопография (in Bulgarian). София: Българска академия на науките. pp. 202–203. ISBN 954-430-264-6. OCLC 38087158.

- ^ Ostrogorsky, Georg (2003). A bizánci állam története. 438. o.: Osiris. ISBN 9633893836.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location (link) - ^ "A görög császár Budán". arcanum.hu. Arcanum Adatbázis Kft.

- ^ a b Magyarország hadtörténete, 74. old.

- ^ The war ended after the army of Louis I defeated the Ottomans in a battle near Nicopolis, however, the outcome of the battle is questioned by Turkish sources

Sources

[edit]- Ferenc Szakály: The stages of the Turkish-Hungarian struggle before the Battle of Mohács (1365-1526), Mohács – Studies, ed.: Lajos Rouzsás and Ferenc Szakály, Akadémia Publishing House, Budapest 1986. ISBN 963-05-3964-0

- Military history of Hungary, Zrínyi military publishing house, Budapest 1985. ed.: Ervin Liptai ISBN 963-32-6337-9

- László Veszprémy: The battles and campaigns of the Árpád and Anjou periods, Zrínyi Military Publishing House, Budapest 2008. ISBN 978-963-327-462-0