History of aviation

This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these messages)

|

The history of aviation spans over two millennia, from the earliest innovations like kites and daring attempts at tower jumping to supersonic and hypersonic flight in powered, heavier-than-air jet aircraft. Kite flying in China, dating back several hundred years BC, is considered the earliest example of man-made flight. Leonardo da Vinci's 15th-century dream of flight found expression in several rational designs, though hindered by the limitations of contemporary science.[citation needed]

In the late 18th century, the Montgolfier brothers invented the hot-air balloon and began manned flights. At almost the same time, the discovery of hydrogen gas led to the invention of the hydrogen balloon.[1] Various theories in mechanics by physicists during the same period, such as fluid dynamics and Newton's laws of motion, led to the foundation of modern aerodynamics, most notably by Sir George Cayley. Balloons, both free-flying and tethered, began to be used for military purposes from the end of the 18th century, with the French government establishing balloon companies during the French Revolution.[2]

Experiments with gliders provided the groundwork for learning the dynamics of heavier-than-air craft, most notably by Cayley, Otto Lilienthal, and Octave Chanute. By the early 20th century, advances in engine technology and aerodynamics made controlled, powered flight possible for the first time. In 1903, following their pioneering research and experiments with wing design and aircraft control, the Wright brothers successfully incorporated all of the required elements to create and fly the first aeroplane.[3] The basic configuration with its characteristic tail was established by 1909, followed by rapid design and performance improvements aided by the development of more powerful engines.

The first great ships of the air were the rigid dirigible balloons pioneered by Ferdinand von Zeppelin, which soon became synonymous with airships and dominated long-distance flight until the 1930s, when large flying boats became popular. After World War II, the flying boats were in their turn replaced by land planes, and the new and immensely powerful jet engine revolutionized both air travel and military aviation.

In the latter half of the 20th century, the development of digital electronics led to major advances in flight instrumentation and "fly-by-wire" systems. The 21st century has seen the widespread use of pilotless drones for military, civilian, and recreational purposes. With digital controls, inherently unstable aircraft designs, such as flying wings, have also become feasible.

Etymology

[edit]The term aviation, noun of action from stem of Latin avis "bird" with suffix -ation meaning action or progress, was coined in 1863 by French pioneer Guillaume Joseph Gabriel de La Landelle (1812–1886) in "Aviation ou Navigation aérienne sans ballons".[4][5]

Primitive beginnings

[edit]Tower jumping

[edit]

Since ancient times, there have been stories of men strapping birdlike wings, stiffened cloaks, or other devices to themselves and attempting to fly, typically by jumping off a tower. The Greek legends of Daedalus and Icarus are some of the earliest known.[6] Others originated in ancient Asia[7] and the European Middle Ages. During this early period, the concepts of lift, stability, and control were not well understood, and most attempts resulted in serious injuries or death.

The Andalusian scientist Abbas ibn Firnas (810–887 AD) attempted to fly in Córdoba, Spain, by covering his body with vulture feathers and attached two wings to his arms.[8][9] The 17th-century Algerian historian Ahmed Mohammed al-Maqqari, quoting a poem by Muhammad I of Córdoba's 9th-century court poet Mu'min ibn Said, recounts that Firnas flew some distance before landing with some injuries, attributed to his lacking a tail (as birds use them to land).[8][10] In the 12th century, William of Malmesbury wrote that Eilmer of Malmesbury, an 11th-century Benedictine monk, attached wings to his hands and feet and flew a short distance,[8] but broke both legs while landing, also having neglected to make himself a tail.[10]

Many others made well-documented jumps in the following centuries. As late as 1811, Albrecht Berblinger constructed an ornithopter and jumped into the Danube at Ulm.[11][page needed]

Kites

[edit]

The kite may have been the first form of man-made aircraft.[1] It was invented in China possibly as far back as the 5th century BC by Mozi (Mo Di) and Lu Ban (Gongshu Ban).[12] Later designs often emulated flying insects, birds, and other beasts, both real and mythical. Some were fitted with strings and whistles to make musical sounds while flying.[13][14][15] Ancient and mediaeval Chinese sources describe kites being used to measure distances, test the wind, lift men, signal, and communicate and send messages.[16]

Kites spread from China around the world. After its introduction into India, the kite further evolved into the fighter kite, which has an abrasive line used to cut down other kites.

Man-carrying kites

[edit]Man-carrying kites are believed to have been used extensively in ancient China for civil and military purposes and sometimes enforced as a punishment. An early recorded flight was that of the prisoner Yuan Huangtou, a Chinese prince, in the 6th century AD.[17] Stories of man-carrying kites also occur in Japan, following the introduction of the kite from China around the seventh century AD. At one time, there was a Japanese law against man-carrying kites.[18]

Rotor wings

[edit]The use of a rotor for vertical flight has existed since 400 BC in the form of the bamboo-copter, an ancient Chinese toy.[19][20] The similar "moulinet à noix" (rotor on a nut) appeared in Europe in the 14th century AD.[21]

Hot air balloons

[edit]From ancient times the Chinese have understood that hot air rises and have applied the principle to a type of small hot air balloon called a sky lantern. A sky lantern consists of a paper balloon under or just inside which a small lamp is placed. Sky lanterns are traditionally launched for pleasure and during festivals. According to Joseph Needham, such lanterns were known in China from the 3rd century BC. Their military use is attributed to the general Zhuge Liang (180–234 AD, honorific title Kongming), who is said to have used them to scare the enemy troops.[22]

There is evidence that the Chinese also "solved the problem of aerial navigation" using balloons, hundreds of years before the 18th century.[23]

Renaissance

[edit]

Eventually, after Ibn Firnas's construction, some investigators began to discover and define some of the basics of rational aircraft design. Most notable of these was Leonardo da Vinci, although his work remained unknown until 1797, and so had no influence on developments over the next three hundred years. While his designs are rational, they are not scientific.[24] He particularly underestimated the amount of power that would be needed to propel a flying object,[25] basing his designs on the flapping wings of a bird rather than an engine-powered propeller.[26]

Leonardo studied bird and bat flight,[25] claiming the superiority of the latter owing to its unperforated wing.[27] He analyzed these and anticipating many principles of aerodynamics. He understood that "An object offers as much resistance to the air as the air does to the object."[28] Isaac Newton did not publish his third law of motion until 1687.

From the last years of the 15th century until 1505,[25] Leonardo wrote about and sketched many designs for flying machines and mechanisms, including ornithopters, fixed-wing gliders, rotorcraft (perhaps inspired by whirligig toys), parachutes (in the form of a wooden-framed pyramidal tent) and a wind speed gauge.[25] His early designs were man-powered and included ornithopters and rotorcraft; however, he came to realise the impracticality of this and later turned to controlled gliding flight, also sketching some designs powered by a spring.[29]

In an essay titled Sul volo (On flight), Leonardo describes a flying machine called "the bird" which he built from starched linen, leather joints, and raw silk thongs. In the Codex Atlanticus, he wrote, "Tomorrow morning, on the second day of January 1496, I will make the thong and the attempt."[26] According to one commonly repeated, albeit presumably fictional story, in 1505 Leonardo or one of his pupils attempted to fly from the summit of Monte Ceceri.[25]

Lighter than air

[edit]Beginnings of modern theories

[edit]Francesco Lana de Terzi proposed in Prodromo dell'Arte Maestra (1670) that large vessels could float in the atmosphere by applying the principles of the vacuum. Lana designed an airship with four huge copper foil spheres connected to support a rider's basket, a tail, and a steering rudder. Critics argued that the thin copper spheres could not sustain ambient air pressure, and further experiments proved that his idea was impossible.[30]

The technique of using a vacuum to create lift is called a vacuum airship, but it is still impossible to build with the materials available today.

In 1709, Bartolomeu de Gusmão approached King John V of Portugal and claimed to have discovered a way for airborne flight.

Due to the King's illness, Gusmão's experiment was rescheduled from its initial June 24, 1709, date to August 8. The experiment was carried out in front of the king and other nobles in the Casa da India yard, but the paper ship or device burned down before it could take flight.[31]

Balloons

[edit]In France, five aviation firsts were accomplished between June 4 and December 1, 1983:

- On 4 June, a crowd gathered in Annonay, France, to witness the unmanned hot air balloon display by the Montgolfier brothers. Their 500-pound balloon ascended to nearly 3,000 feet and traveled over a mile and a half. It stayed in the air for ten minutes before tipping over and catching fire.[32][33]

- On August 27th, Jacques Charles and the Robert brothers unveiled the first unmanned hydrogen balloon from Paris' Champ de Mars. It landed almost an hour later in Gonesse, where terrified farmers mistook it for a monster and destroyed it.[34]

- On October 19, in front of 2,000 spectators, Jean-François Pilâtre de Rozier and the Marquis d'Arlandes boarded the Montgolfier aircraft as the first people. Later that day, Giroud de Villette, another pilot, took to the skies much higher.[35]

- On 21 November, the Montgolfiers launched the first free flight with human passengers. King Louis XVI had originally decreed that condemned criminals would be the first pilots, but Jean-François Pilâtre de Rozier, along with the Marquis François d'Arlandes, successfully petitioned for the honour. They drifted 8 km (5.0 mi) in a balloon powered by a wood fire.[33]

- On 1 December, Jacques Charles and the Nicolas-Louis Robert launched their manned hydrogen balloon from the Jardin des Tuileries in Paris, as a crowd of 400,000 witnessed. They ascended to a height of about 1,800 feet (550 m)[15] and landed at sunset in Nesles-la-Vallée after a flight of 2 hours and 5 minutes, covering 36 km. After Robert alighted Charles decided to ascend alone. This time he ascended rapidly to an altitude of about 9,800 feet (3,000 m), where he saw the sun again, suffered extreme pain in his ears, and never flew again.

Ballooning became a major "rage" in Europe in the late 18th century, providing the first detailed understanding of the relationship between altitude and the atmosphere.

Non-steerable balloons were employed during the American Civil War by the Union Army Balloon Corps. The young Ferdinand von Zeppelin first flew as a balloon passenger with the Union Army of the Potomac in 1863.

In the early 1900s, ballooning was a popular sport in Britain. These privately owned balloons usually used coal gas as the lifting gas. This has half the lifting power of hydrogen so the balloons had to be larger, however, coal gas was far more readily available and the local gas works sometimes provided a special lightweight formula for ballooning events.[36]

Airships

[edit]

Airships were originally called "dirigible balloons" and are still sometimes called dirigibles today.

Work on developing a steerable (or dirigible) balloon continued sporadically throughout the 19th century. The first powered, controlled, sustained lighter-than-air flight is believed to have taken place in 1852 when Henri Giffard flew 15 miles (24 km) in France, with a steam engine-driven craft.

Another advance was made in 1884, when the first fully controllable free-flight was made in a French Army electric-powered airship, La France, by Charles Renard and Arthur Krebs. The 170-foot (52 m) long, 66,000-cubic-foot (1,900 m3) airship covered 8 km (5.0 mi) in 23 minutes with the aid of an 8½ horsepower electric motor.

However, these aircraft were generally short-lived and extremely frail. Routine, controlled flights did not occur until the advent of the internal combustion engine (see below.)

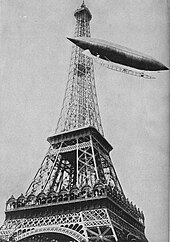

The first aircraft to make routine controlled flights were non-rigid airships (sometimes called "blimps".) The most successful early pioneering pilot of this type of aircraft was the Brazilian Alberto Santos-Dumont who effectively combined a balloon with an internal combustion engine. On 19 October 1901, he flew his airship Number 6 over Paris from the Parc de Saint Cloud around the Eiffel Tower and back in under 30 minutes to win the Deutsch de la Meurthe prize. Santos-Dumont went on to design and build several aircraft. The subsequent controversy surrounding his and others' competing claims with regard to aircraft overshadowed his great contribution to the development of airships.

At the same time that non-rigid airships were starting to have some success, the first successful rigid airships were also being developed. These were far more capable than fixed-wing aircraft in terms of pure cargo-carrying capacity for decades. Rigid airship design and advancement was pioneered by the German count Ferdinand von Zeppelin.

Construction of the first Zeppelin airship began in 1899 in a floating assembly hall on Lake Constance in the Bay of Manzell, Friedrichshafen. This was intended to ease the starting procedure, as the hall could easily be aligned with the wind. The prototype airship LZ 1 (LZ for "Luftschiff Zeppelin") had a length of 128 m (420 ft) was driven by two 10.6 kW (14.2 hp) Daimler engines and balanced by moving a weight between its two nacelles.

Its first flight, on 2 July 1900, lasted for only 18 minutes, as LZ 1 was forced to land on the lake after the winding mechanism for the balancing weight had broken. Upon repair, the technology proved its potential in subsequent flights, bettering the 6 m/s speed attained by the French airship La France by 3 m/s, but could not yet convince possible investors. It was several years before the Count was able to raise enough funds for another try.

German airship passenger service known as DELAG (Deutsche-Luftschiffahrts AG) was established in 1910.

Although airships were used in both World War I and II, and continue on a limited basis to this day, their development has been largely overshadowed by heavier-than-air craft.

Heavier than air

[edit]17th and 18th centuries

[edit]Traveller Evliya Çelebi reported that in 1633, Ottoman scientist and engineer Lagari Hasan Çelebi blasted off from Sarayburnu, (the promontory below the Topkapı Palace in Istanbul) in a 7-winged rocket propelled by 50 okka (140 lbs) of gunpowder. The flight was said to have been undertaken at the time of the birth of Sultan Murad IV's daughter. As Evliya Celebi wrote, Lagari proclaimed before launching his craft "O my sultan! Be blessed, I am going to talk to Jesus!"; after ascending in the rocket, he landed in the sea, swimming ashore and joking "O my sultan! Jesus sends his regards to you!"; he was rewarded by the Sultan with silver and the rank of sipahi in the Ottoman army.[37][38] Evliya Çelebi also wrote of Lagari's brother, Hezârfen Ahmed Çelebi, making a flight by glider a year earlier.

Italian inventor Tito Livio Burattini, invited by the Polish King Władysław IV to his court in Warsaw, built a model aircraft with four fixed glider wings in 1647.[39] Described as "four pairs of wings attached to an elaborate 'dragon'", it was said to have successfully lifted a cat in 1648 but not Burattini himself.[40] He promised that "only the most minor injuries" would result from landing the craft.[41] His "Dragon Volant" is considered "the most elaborate and sophisticated aeroplane to be built before the 19th Century".[42]

The first published paper on aviation was "Sketch of a Machine for Flying in the Air" by Emanuel Swedenborg published in 1716.[43] This flying machine consisted of a light frame covered with strong canvas and provided with two large oars or wings moving on a horizontal axis, arranged so that the upstroke met with no resistance while the downstroke provided lifting power. Swedenborg knew that the machine would not fly, but suggested it as a start and was confident that the problem would be solved. He wrote: "It seems easier to talk of such a machine than to put it into actuality, for it requires greater force and less weight than exists in a human body. The science of mechanics might perhaps suggest a means, namely, a strong spiral spring. If these advantages and requisites are observed, perhaps in time to come someone might know how better to utilise our sketch and cause some addition to be made so as to accomplish that which we can only suggest. Yet there are sufficient proofs and examples from nature that such flights can take place without danger, although when the first trials are made you may have to pay for the experience, and not mind an arm or leg". Swedenborg proved prescient in his observation that a method of powering of an aircraft was one of the critical problems to be overcome.

On 16 May 1793, the Spanish inventor Diego Marín Aguilera managed to cross the river Arandilla in Coruña del Conde, Castile, flying 300 – 400 m, with a flying machine.[44]

19th century

[edit]Balloon jumping replaced tower jumping, also demonstrating with typically fatal results that man-power and flapping wings were useless in achieving flight. At the same time scientific study of heavier-than-air flight began in earnest. In 1801, the French officer André Guillaume Resnier de Goué managed a 300-metre glide by starting from the top of the city walls of Angoulême and broke only one leg on arrival.[45] In 1837 French mathematician and brigadier general Isidore Didion stated, "Aviation will be successful only if one finds an engine whose ratio with the weight of the device to be supported will be larger than current steam machines or the strength developed by humans or most of the animals".[46]

Sir George Cayley and the first modern aircraft

[edit]Sir George Cayley was first called the "father of the aeroplane" in 1846.[47] During the last years of the previous century he had begun the first rigorous study of the physics of flight and later designed the first modern heavier-than-air craft. Among his many achievements, his most important contributions to aeronautics include:

- Clarifying our ideas and laying down the principles of heavier-than-air flight.

- Reaching a scientific understanding of the principles of bird flight.

- Conducting scientific aerodynamic experiments demonstrating drag and streamlining, movement of the centre of pressure, and the increase in lift from curving the wing surface.

- Defining the modern aeroplane configuration comprising a fixed-wing, fuselage and tail assembly.

- Demonstrations of manned, gliding flight.

- Setting out the principles of power-to-weight ratio in sustaining flight.

Cayley's first innovation was to study the basic science of lift by adopting the whirling arm test rig for use in aircraft research and using simple aerodynamic models on the arm, rather than attempting to fly a model of a complete design.

In 1799, he set down the concept of the modern aeroplane as a fixed-wing flying machine with separate systems for lift, propulsion, and control.[48][49]

In 1804, Cayley constructed a model glider which was the first modern heavier-than-air flying machine, having the layout of a conventional modern aircraft with an inclined wing towards the front and adjustable tail at the back with both tailplane and fin. A movable weight allowed adjustment of the model's centre of gravity.[50]

In 1809, goaded by the farcical antics of his contemporaries (see above), he began the publication of a landmark three-part treatise titled "On Aerial Navigation" (1809–1810).[51] In it he wrote the first scientific statement of the problem, "The whole problem is confined within these limits, viz. to make a surface support a given weight by the application of power to the resistance of air". He identified the four vector forces that influence an aircraft: thrust, lift, drag and weight and distinguished stability and control in his designs. He also identified and described the importance of the cambered aerofoil, dihedral, diagonal bracing and drag reduction, and contributed to the understanding and design of ornithopters and parachutes.

In 1848, he had progressed far enough to construct a glider in the form of a triplane large and safe enough to carry a child. A local boy was chosen but his name is not known.[52][53]

He went on to publish in 1852 the design for a full-size manned glider or "governable parachute" to be launched from a balloon and then to construct a version capable of launching from the top of a hill, which carried the first adult aviator across Brompton Dale in 1853.

Minor inventions included the rubber-powered motor,[citation needed] which provided a reliable power source for research models. By 1808, he had even re-invented the wheel, devising the tension-spoked wheel in which all compression loads are carried by the rim, allowing a lightweight undercarriage.[54]

Age of steam

[edit]Drawing directly from Cayley's work, Henson's 1842 design for an aerial steam carriage broke new ground. Although only a design, it was the first in history for a propeller-driven fixed-wing aircraft.

1866 saw the founding of the Aeronautical Society of Great Britain and two years later the world's first aeronautical exhibition was held at the Crystal Palace, London,[55] where John Stringfellow was awarded a £100 prize for the steam engine with the best power-to-weight ratio.[56][57][58] In 1848, Stringfellow achieved the first powered flight using an unmanned 10 feet (3.0 m) wingspan steam-powered monoplane built in a disused lace factory in Chard, Somerset. Employing two contra-rotating propellers on the first attempt, made indoors, the machine flew ten feet before becoming destabilised, damaging the craft. The second attempt was more successful, the machine leaving a guidewire to fly freely, achieving thirty yards of straight and level powered flight.[59][60][61] Francis Herbert Wenham presented the first paper to the newly formed Aeronautical Society (later the Royal Aeronautical Society), On Aerial Locomotion. He advanced Cayley's work on cambered wings, making important findings. To test his ideas, from 1858 he had constructed several gliders, both manned and unmanned, and with up to five stacked wings. He realised that long, thin wings are better than bat-like ones because they have more leading edge for their area. Today this relationship is known as the aspect ratio of a wing.

The latter part of the 19th century became a period of intense study, characterized by the "gentleman scientists" who represented most research efforts until the 20th century. Among them was the British scientist-philosopher and inventor Matthew Piers Watt Boulton, who studied lateral flight control and was the first to patent an aileron control system in 1868.[62][63][64][65]

In 1871, Wenham made the first wind tunnel using a fan, driven by a steam engine, to propel air down a 12 ft (3.7 m) tube to the model.[66]

Meanwhile, the British advances had galvanised French researchers. In 1857, Félix du Temple proposed a monoplane with a tailplane and retractable undercarriage. Developing his ideas with a model powered first by clockwork and later by steam, he eventually achieved a short hop with a full-size manned craft in 1874. It achieved lift-off under its own power after launching from a ramp, glided for a short time and returned safely to the ground, making it the first successful powered glide in history.

In 1865, Louis Pierre Mouillard published an influential book The Empire Of The Air (l'Empire de l'Air).

In 1856, Frenchman Jean-Marie Le Bris made the first flight higher than his point of departure, by having his glider "L'Albatros artificiel" pulled by a horse on a beach. He reportedly achieved a height of 100 metres, over a distance of 200 metres.

Alphonse Pénaud, a Frenchman, advanced the theory of wing contours and aerodynamics and constructed successful models of aeroplanes, helicopters and ornithopters. In 1871 he flew the first aerodynamically stable fixed-wing aeroplane, a model monoplane he called the "Planophore", a distance of 40 m (130 ft). Pénaud's model incorporated several of Cayley's discoveries, including the use of a tail, wing dihedral for inherent stability, and rubber power. The planophore also had longitudinal stability, being trimmed such that the tailplane was set at a smaller angle of incidence than the wings, an original and important contribution to the theory of aeronautics.[67] Pénaud's later project for an amphibian aeroplane, although never built, incorporated other modern features. A tailless monoplane with a single vertical fin and twin tractor propellers, it also featured hinged rear elevator and rudder surfaces, retractable undercarriage and a fully enclosed, instrumented cockpit.

Equally authoritative as a theorist was Pénaud's fellow countryman Victor Tatin. In 1879, he flew a model which, like Pénaud's project, was a monoplane with twin tractor propellers but also had a separate horizontal tail. It was powered by compressed air. Flown tethered to a pole, this was the first model to take off under its own power.

In 1884, Alexandre Goupil published his work La Locomotion Aérienne (Aerial Locomotion), although the flying machine he later constructed failed to fly.

In 1890, the French engineer Clément Ader completed the first of three steam-driven flying machines, the Éole. On 9 October 1890, Ader made an uncontrolled hop of around 50 metres (160 ft); this was the first manned aeroplane to take off under its own power.[68] His Avion III of 1897, notable only for having twin steam engines, failed to fly:[69] Ader later claimed success and was not debunked until 1910 when the French Army published its report on his attempt.

Sir Hiram Maxim was an American engineer who had moved to England. He built his own whirling arm rig and wind tunnel and constructed a large machine with a wingspan of 105 feet (32 m), a length of 145 feet (44 m), fore and aft horizontal surfaces and a crew of three. Twin propellers were powered by two lightweight compound steam engines each delivering 180 hp (130 kW). The overall weight was 8,000 pounds (3,600 kg). It was intended as a test rig to investigate aerodynamic lift: lacking flight controls it ran on rails, with a second set of rails above the wheels to restrain it. Completed in 1894, on its third run it broke from the rail, became airborne for about 200 yards at two to three feet of altitude[70] and was badly damaged upon falling back to the ground. It was subsequently repaired, but Maxim abandoned his experiments shortly afterwards.[71]

Learning to glide; Otto Lilienthal and the first human flights

[edit]

Around the last decade of the 19th century, a number of key figures were refining and defining the modern aeroplane. Lacking a suitable engine, aircraft work focused on stability and control in gliding flight. In 1879, Biot constructed a bird-like glider with the help of Massia and flew in it briefly. It is preserved in the Musee de l'Air, France, and is claimed to be the earliest man-carrying flying machine still in existence.

The Englishman Horatio Phillips made key contributions to aerodynamics. He conducted extensive wind tunnel research on aerofoil sections, proving the principles of aerodynamic lift foreseen by Cayley and Wenham. His findings underpin all modern aerofoil design. Between 1883 and 1886, the American John Joseph Montgomery developed a series of three manned gliders, before conducting his own independent investigations into aerodynamics and circulation of lift.

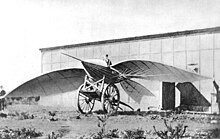

Otto Lilienthal became known as the "Glider King" or "Flying Man" of Germany. He duplicated Wenham's work and greatly expanded on it in 1884, publishing his research in 1889 as Birdflight as the Basis of Aviation (Der Vogelflug als Grundlage der Fliegekunst), which is seen as one of the most important works in aviation history.[72] He also produced a series of hang gliders, including bat-wing, monoplane and biplane forms, such as the Derwitzer Glider and Normal soaring apparatus, which is considered to be the first air plane in series production, making the Maschinenfabrik Otto Lilienthal the first air plane production company in the world.[73]

Starting in 1891, he became the first person to make controlled untethered glides routinely, and the first to be photographed flying a heavier-than-air machine, stimulating interest around the world. Lilienthal's work led to him developing the concept of the modern wing.[74][75] His flights in the year 1891 are seen as the beginning of human flight[76] and because of that he is often referred to as either the "father of aviation"[77][78][79] or "father of flight".[80]

He rigorously documented his work, including photographs, and for this reason is one of the best known of the early pioneers. Lilienthal made over 2,000 glides until his death in 1896 from injuries sustained in a glider crash.

Picking up where Lilienthal left off, Octave Chanute took up aircraft design after an early retirement, and funded the development of several gliders. In the summer of 1896, his team flew several of their designs eventually deciding that the best was a biplane design. Like Lilienthal, he documented and photographed his work.

In Britain Percy Pilcher, who had worked for Maxim, built and successfully flew several gliders during the mid to late 1890s.

The invention of the box kite during this period by the Australian Lawrence Hargrave led to the development of the practical biplane. In 1894, Hargrave linked four of his kites together, added a sling seat, and was the first to obtain lift with a heavier than air aircraft, when he flew up 16 feet (4.9 m). Later pioneers of manned kite flying included Samuel Franklin Cody in England and Captain Génie Saconney in France.

Frost

[edit]William Frost from Pembrokeshire, Wales started his project in 1880 and after 16 years, he designed a flying machine and in 1894 won a patent for a "Frost Aircraft Glider". Reports say witnesses claimed the craft flew at Saundersfoot in 1896, travelling 500 yards before colliding with a tree and falling in a field.[81]

Langley

[edit]

After a distinguished career in astronomy and shortly before becoming Secretary of the Smithsonian Institution, Samuel Pierpont Langley started a serious investigation into aerodynamics at what is today the University of Pittsburgh. In 1891, he published Experiments in Aerodynamics detailing his research, and then turned to building his designs. He hoped to achieve automatic aerodynamic stability, so he gave little consideration to in-flight control.[82] On 6 May 1896, Langley's Aerodrome No. 5 made the first successful sustained flight of an unpiloted, engine-driven heavier-than-air craft of substantial size. It was launched from a spring-actuated catapult mounted on top of a houseboat on the Potomac River near Quantico, Virginia. Two flights were made that afternoon, one of 1,005 metres (3,297 ft) and a second of 700 metres (2,300 ft), at a speed of approximately 25 miles per hour (40 km/h). On both occasions, the Aerodrome No. 5 landed in the water as planned, because, in order to save weight, it was not equipped with landing gear. On 28 November 1896, another successful flight was made with the Aerodrome No. 6. This flight, of 1,460 metres (4,790 ft), was witnessed and photographed by Alexander Graham Bell. The Aerodrome No. 6 was actually Aerodrome No. 4 greatly modified. So little remained of the original aircraft that it was given a new designation.

With the successes of the Aerodrome No. 5 and No. 6, Langley started looking for funding to build a full-scale man-carrying version of his designs. Spurred by the Spanish–American War, the U.S. government granted him $50,000 to develop a man-carrying flying machine for aerial reconnaissance. Langley planned on building a scaled-up version known as the Aerodrome A, and started with the smaller Quarter-scale Aerodrome, which flew twice on 18 June 1901, and then again with a newer and more powerful engine in 1903.

With the basic design apparently successfully tested, he then turned to the problem of a suitable engine. He contracted Stephen Balzer to build one, but was disappointed when it delivered only 8 hp (6.0 kW) instead of the 12 hp (8.9 kW) he expected. Langley's assistant, Charles M. Manly, then reworked the design into a five-cylinder water-cooled radial that delivered 52 hp (39 kW) at 950 rpm, a feat that took years to duplicate. Now with both power and a design, Langley put the two together with great hopes.

To his dismay, the resulting aircraft proved to be too fragile. Simply scaling up the original small models resulted in a design that was too weak to hold itself together. Two launches in late 1903 both ended with the Aerodrome immediately crashing into the water. The pilot, Manly, was rescued each time. Also, the aircraft's control system was inadequate to allow quick pilot responses, and it had no method of lateral control, and the Aerodrome's aerial stability was marginal.[82]

Langley's attempts to gain further funding failed, and his efforts ended. Nine days after his second abortive launch on 8 December, the Wright brothers successfully flew their Flyer. Glenn Curtiss made 93 modifications to the Aerodrome and flew this very different aircraft in 1914.[82] Without acknowledging the modifications, the Smithsonian Institution asserted that Langley's Aerodrome was the first machine "capable of flight".[83]

Whitehead

[edit]Gustave Weißkopf was a German who emigrated to the U.S., where he soon changed his name to Whitehead. From 1897 to 1915, he designed and built early flying machines and engines. On 14 August 1901, two and a half years before the Wright Brothers' flight, he claimed to have carried out a controlled, powered flight in his Number 21 monoplane at Fairfield, Connecticut. The flight was reported in the Bridgeport Sunday Herald local newspaper. About 30 years later, several people questioned by a researcher claimed to have seen that or other Whitehead flights.[citation needed]

In March 2013, Jane's All the World's Aircraft, an authoritative source for contemporary aviation, published an editorial which accepted Whitehead's flight as the first manned, powered, controlled flight of a heavier-than-air craft.[84] The Smithsonian Institution (custodians of the original Wright Flyer) and many aviation historians continue to maintain that Whitehead did not fly as suggested.[85][86] The historians of the Royal Aeronautical Society noted that: "All available evidence fails to support the claim that Gustave Whitehead made sustained, powered, controlled flights predating those of the Wright brothers."[87] The editors of Scientific American agree: "The data show that not only was Whitehead not first in flight, but that he may never have made a controlled, powered flight at any time."[88]

Pearse

[edit]Richard Pearse was a New Zealand farmer and inventor who performed pioneering aviation experiments. Witnesses interviewed many years afterward claimed that Pearse flew and landed a powered heavier-than-air machine on 31 March 1903, nine months before the Wright brothers flew. [89]: 21–30 Documentary evidence for these claims remains open to interpretation and dispute, and Pearse himself never made such claims. In a newspaper interview in 1909, he said he did not "attempt anything practical ... until 1904".[90] If he did fly in 1903, the flight appears to have been poorly controlled in comparison to the Wrights'.

Wright brothers

[edit]

Using a methodical approach and concentrating on the controllability of the aircraft, the brothers built and tested a series of kite and glider designs from 1898 to 1902 before attempting to build a powered design. The gliders worked, but not as well as the Wrights had expected based on the experiments and writings of their predecessors. Their first full-size glider, launched in 1900, had only about half the lift they anticipated. Their second glider, built the following year, performed even more poorly. Rather than giving up, the Wrights constructed their own wind tunnel and created a number of sophisticated devices to measure lift and drag on the 200 wing designs they tested.[91] As a result, the Wrights corrected earlier mistakes in calculations regarding drag and lift. Their testing and calculating produced a third glider with a higher aspect ratio and true three-axis control. They flew it successfully hundreds of times in 1902, and it performed far better than the previous models. By using a rigorous system of experimentation, involving wind-tunnel testing of airfoils and flight testing of full-size prototypes, the Wrights not only built a working aircraft the following year, the Wright Flyer, but also helped advance the science of aeronautical engineering.

The Wrights appear to be the first to make serious studied attempts to simultaneously solve the power and control problems. Both problems proved difficult, but they never lost interest. They solved the control problem by inventing wing warping for roll control, combined with simultaneous yaw control with a steerable rear rudder. Almost as an afterthought, they designed and built a low-powered internal combustion engine. They also designed and carved wooden propellers that were more efficient than any before, enabling them to gain adequate performance from their low engine power. Although wing-warping as a means of lateral control was used only briefly during the early history of aviation, the principle of combining lateral control in combination with a rudder was a key advance in aircraft control. While many aviation pioneers appeared to leave safety largely to chance, the Wrights' design was greatly influenced by the need to teach themselves to fly without unreasonable risk to life and limb, by surviving crashes. This emphasis, as well as low engine power, was the reason for low flying speed and for taking off in a headwind. Performance, rather than safety, was the reason for the rear-heavy design because the canard could not be highly loaded; anhedral wings were less affected by crosswinds and were consistent with the low yaw stability.

According to the Smithsonian Institution and Fédération Aéronautique Internationale (FAI),[94][95] the Wrights made the first sustained, controlled, powered heavier-than-air manned flight at Kill Devil Hills, North Carolina, four miles (8 km) south of Kitty Hawk, North Carolina on 17 December 1903.[96]

The first flight by Orville Wright, of 120 feet (37 m) in 12 seconds, was recorded in a famous photograph. In the fourth flight of the same day, Wilbur Wright flew 852 feet (260 m) in 59 seconds. The flights were witnessed by three coastal lifesaving crewmen, a local businessman, and a boy from the village, making these the first public flights and the first well-documented ones.[96]

Orville described the final flight of the day: "The first few hundred feet were up and down, as before, but by the time three hundred feet had been covered, the machine was under much better control. The course for the next four or five hundred feet had but little undulation. However, when out about eight hundred feet the machine began pitching again, and, in one of its darts downward, struck the ground. The distance over the ground was measured to be 852 feet (260 m); the time of the flight was 59 seconds. The frame supporting the front rudder was badly broken, but the main part of the machine was not injured at all. We estimated that the machine could be put in condition for flight again in about a day or two".[97] They flew only about ten feet above the ground as a safety precaution, so they had little room to manoeuvre, and all four flights in the gusty winds ended in a bumpy and unintended "landing". Modern analysis by Professor Fred E. C. Culick and Henry R. Rex (1985) has demonstrated that the 1903 Wright Flyer was so unstable as to be almost unmanageable by anyone but the Wrights, who had trained themselves in the 1902 glider.[98]

The Wrights continued flying at Huffman Prairie near Dayton, Ohio in 1904–05. In May 1904 they introduced the Flyer II, a heavier and improved version of the original Flyer. On 23 June 1905, they first flew a third machine, the Flyer III. After a severe crash on 14 July 1905, they rebuilt the Flyer III and made important design changes. They almost doubled the size of the elevator and rudder and moved them about twice the distance from the wings. They added two fixed vertical vanes (called "blinkers") between the elevators and gave the wings a very slight dihedral. They disconnected the rudder from the wing-warping control, and as in all future aircraft, placed it on a separate control handle. When flights resumed the results were immediate. The serious pitch instability that hampered Flyers I and II was significantly reduced, so repeated minor crashes were eliminated. Flights with the redesigned Flyer III started lasting over 10 minutes, then 20, then 30. Flyer III became the first practical aircraft (though without wheels and needing a launching device), flying consistently under full control and bringing its pilot back to the starting point safely and landing without damage. On 5 October 1905, Wilbur flew 24 miles (39 km) in 39 minutes 23 seconds.[99]

According to the April 1907 issue of the Scientific American magazine,[100] the Wright brothers seemed to have the most advanced knowledge of heavier-than-air navigation at the time. However, the same magazine issue also claimed that no public flight had been made in the United States before its April 1907 issue. Hence, they devised the Scientific American Aeronautic Trophy in order to encourage the development of a heavier-than-air flying machine. Glenn H. Curtiss won the trophy in 1908 with the first pre-announced and officially recorded flight of the June Bug.[101]

History

[edit]Pioneer Era (1903–1914)

[edit]This period saw the development of practical aeroplanes and airships and their early application, alongside balloons and kites, for private, sport and military use.

Pioneers in Europe

[edit]

Although full details of the Wright Brothers' system of flight control had been published in l'Aerophile in January 1906, the importance of this advance was not recognised, and European experimenters generally concentrated on attempting to produce inherently stable machines.

Short powered flights were performed in France by Romanian engineer Traian Vuia on 18 March and 19 August 1906 when he flew 12 and 24 metres, respectively, in a self-designed, fully self-propelled, fixed-wing aircraft, that possessed a fully wheeled undercarriage.[102][103] He was followed by Jacob Ellehammer who built a monoplane which he tested with a tether in Denmark on 12 September 1906, flying 42 metres.[104]

On 13 September 1906, the Brazilian Alberto Santos-Dumont made a public flight in Paris with the 14-bis, also known as Oiseau de proie (French for "bird of prey"). This was of canard configuration with pronounced wing dihedral, and covered a distance of 60 m (200 ft) on the grounds of the Chateau de Bagatelle in Paris' Bois de Boulogne before a large crowd of witnesses. This well-documented event was the first flight verified by the Aéro-Club de France of a powered heavier-than-air machine in Europe and won the Deutsch-Archdeacon Prize for the first officially observed flight greater than 25 m (82 ft). On 12 November 1906, Santos-Dumont set the first world record recognized by the Federation Aeronautique Internationale by flying 220 m (720 ft) in 21.5 seconds.[105][106] Only one more brief flight was made by the 14-bis in March 1907, after which it was abandoned.[107]

In March 1907, Gabriel Voisin flew the first example of his Voisin biplane. On 13 January 1908, a second example of the type was flown by Henri Farman to win the Deutsch-Archdeacon Grand Prix d'Aviation prize for a flight in which the aircraft flew a distance of more than a kilometre and landed at the point where it had taken off. The flight lasted 1 minute and 28 seconds.[108]

Flight as an established technology

[edit]

Santos-Dumont later added ailerons between the wings in an effort to gain more lateral stability. His final design, first flown in 1907, was the series of Demoiselle monoplanes (Nos. 19 to 22). The Demoiselle No 19 could be constructed in only 15 days and became the world's first series production aircraft. The Demoiselle achieved 120 km/h.[109] The fuselage consisted of three specially reinforced bamboo booms: the pilot sat in a seat between the main wheels of a conventional landing gear whose pair of wire-spoked mainwheels were located at the lower front of the airframe, with a tailskid half-way back beneath the rear fuselage structure. The Demoiselle was controlled in flight by a cruciform tail unit hinged on a form of universal joint at the aft end of the fuselage structure to function as elevator and rudder, with roll control provided through wing warping (No. 20), with the wings only warping "down".

In 1908, Wilbur Wright travelled to Europe, and starting in August gave a series of flight demonstrations at Le Mans in France. The first demonstration, made on 8 August, attracted an audience including most of the major French aviation experimenters, who were astonished by the clear superiority of the Wright Brothers' aircraft, particularly its ability to make tight controlled turns.[110] The importance of using roll control in making turns was recognised by almost all the European experimenters: Henri Farman fitted ailerons to his Voisin biplane and shortly afterwards set up his own aircraft construction business, whose first product was the influential Farman III biplane.

The following year saw the widespread recognition of powered flight as something other than the preserve of dreamers and eccentrics. On 25 July 1909, Louis Blériot won worldwide fame by winning a £1,000 prize offered by the British Daily Mail newspaper for a flight across the English Channel, and in August around half a million people, including the President of France Armand Fallières and David Lloyd George, attended one of the first aviation meetings, the Grande Semaine d'Aviation at Reims.

In 1914, pioneering aviator Tony Jannus captained the inaugural flight of the St. Petersburg-Tampa Airboat Line, the world's first commercial passenger airline.

Historians disagree about whether the Wright brothers patent war impeded development of the aviation industry in the United States compared to Europe. The patent war ended during World War I when the government pressured the industry into forming a patent pool, and major litigants had left the industry.

Rotorcraft

[edit]

In 1877, the Italian engineer, inventor and aeronautical pioneer Enrico Forlanini developed an unmanned helicopter powered by a steam engine. It rose to a height of 13 metres (43 feet), where it remained for 20 seconds, after a vertical take-off from a park in Milan.[111] Milan has dedicated to Enrico Forlanini its city airport, also named Linate Airport,[112] as well as the nearby park, the Parco Forlanini.[113] In Milan he also has an avenue named after him, Viale Enrico Forlanini.

The first time a manned helicopter is known to have risen off the ground was on a tethered flight in 1907 by the Breguet-Richet Gyroplane. Later the same year the Cornu helicopter, also French, made the first rotary-winged free flight at Lisieux, France. However, these were not practical designs.

Military use

[edit]

Almost as soon as they were invented, aeroplanes were used for military purposes. The first country to use them for military purposes was Italy, whose aircraft made reconnaissance, bombing and artillery correction flights in Libya during the Italian-Turkish war (September 1911 – October 1912). This war also saw Ottoman soldiers shoot down a warplane for the first time in history, the first warplane reconnaissance mission flown on 23 October 1911 by the Italian air force's Captain Carlo Piazza, and the first bombing mission flown on 1 November 1911 by Italy's Second Lieutenant Giolio Gavotti.[114][115] Bulgaria later followed this example. Its aeroplanes attacked and reconnoitred Ottoman positions during the First Balkan War 1912–13. The first war to see major use of aeroplanes in offensive, defensive and reconnaissance capabilities was World War I. The Allies and Central Powers both used aeroplanes and airships extensively.

While the concept of using the aeroplane as an offensive weapon was generally discounted before World War I,[116] the idea of using it for photography was one that was not lost on any of the major forces. All of the major forces in Europe had light aircraft, typically derived from pre-war sporting designs, attached to their reconnaissance departments. Radiotelephones were also being explored on aeroplanes, notably the SCR-68, as communication between pilots and ground commander grew more and more important.

World War I (1914–1918)

[edit]

Combat schemes

[edit]It was not long before aircraft were shooting at each other, but the lack of any sort of steady point for the gun was a problem. The French solved this problem when, in late 1914, Roland Garros attached a fixed machine gun to the front of his plane, but while Adolphe Pegoud became known as the first "ace", getting credit for five victories before also becoming the first ace to die in action, it was German Luftstreitkräfte Leutnant Kurt Wintgens who, on 1 July 1915, scored the very first aerial victory by a purpose-built fighter plane, with a synchronized machine gun.

Aviators were styled as modern-day knights, doing individual combat with their enemies. Several pilots became famous for their air-to-air combat; the most well known is Manfred von Richthofen, better known as the "Red Baron", who shot down 80 planes in air-to-air combat with several different planes, the most celebrated of which was the Fokker Dr.I. On the Allied side, René Paul Fonck is credited with the most all-time victories at 75, even when later wars are considered.

France, Britain, Germany, and Italy were the leading manufacturers of fighter planes that saw action during the war,[citation needed] with German aviation technologist Hugo Junkers showing the way to the future through his pioneering use of all-metal aircraft from late 1915.

Between the World Wars (1918–1939)

[edit]

The years between World War I and World War II saw great advancements in aircraft technology. Airplanes evolved from low-powered biplanes made from wood and fabric to sleek, high-powered monoplanes made of aluminum, based primarily on the founding work of Hugo Junkers during the World War I period and its adoption by American designer William Bushnell Stout and Soviet designer Andrei Tupolev.[117]

After World War I, experienced fighter pilots were eager to show off their skills. Many American pilots became barnstormers, flying into small towns across the country and showing off their flying abilities, as well as taking paying passengers for rides. Eventually, the barnstormers grouped into more organized displays. Air shows sprang up around the country, with air races, acrobatic stunts, and feats of air superiority.[118] The air races drove engine and airframe development—the Schneider Trophy, for example, led to a series of ever faster and sleeker monoplane designs culminating in the Supermarine S.6B.[119] With pilots competing for cash prizes, there was an incentive to go faster. Amelia Earhart was perhaps the most famous of those on the barnstorming/air show circuit. She was also the first female pilot to achieve records such as the crossing of the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans.

Prizes for distance and speed records also drove development forwards. On 14 June 1919, Captain John Alcock and Lieutenant Arthur Brown co-piloted a Vickers Vimy non-stop from St. John's, Newfoundland to Clifden, Ireland, winning the £13,000 ($65,000).[120] Northcliffe prize. The first flight across the South Atlantic and the first aerial crossing using astronomical navigation, was made by the naval aviators Gago Coutinho and Sacadura Cabral in 1922, from Lisbon, Portugal, to Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, using an aircraft fitted with an artificial horizon for aeronautical use.[121] In 1924, Major General Mason Patrick lead a group of U.S. Army Air Service members to complete the first aerial circumnavigation of the world. This flight around the world came with many logistical challenges, traveling 26,343 miles over the span of 175 days. This flight led to improved foreign relations through by promoting commercial collaboration, and greater public interest in aviation, prompting governments to put more resources into developing their aviation forces.[122] On May 21, 1927, Charles Lindbergh received the Orteig Prize of $25,000 for the first solo non-stop crossing of the Atlantic. This caused what was known in aviation at the time as the "Lindbergh boom", which increased public interest in aviation.[123]

Australian Sir Charles Kingsford Smith was the first to fly across the larger Pacific Ocean in the Southern Cross. His crew left Oakland, California to make the first trans-Pacific flight to Australia, making three stops to complete the journey. Kingsford-Smith and his crew made their first stop in Hawaii from Oakland, California, and from Hawaii to Suva, Fiji. During the last segment of their journey from Fiji to Brisbane, Australia, they encountered severe thunderstorms, thrown nearly 140 miles off their course. The flight concluded on June 9, 1928 after flying 7,230 miles, Kingsford-Smith and his crew landed in Brisbane, Australia, receiving $25,000 dollars from the Australian government for their achievement.[124][125] Accompanying him were Australian aviator Charles Ulm as the relief pilot, and the Americans James Warner and Captain Harry Lyon (who were the radio operator, navigator and engineer). A week after they landed, Kingsford Smith and Ulm recorded a disc for Columbia talking about their trip. With Ulm, Kingsford Smith later continued his journey being the first in 1929 to circumnavigate the world, crossing the equator twice.[126]

The first lighter-than-air crossings of the Atlantic were made by airship in July 1919 by His Majesty's Airship R34 and crew when they flew from East Lothian, Scotland to Long Island, New York and then back to Pulham, England.[127] By 1929, airship technology had advanced to the point that the first round-the-world flight was completed by the Graf Zeppelin in September and in October, the same aircraft inaugurated the first commercial transatlantic service.[128] However, the age of the rigid airship ended following the destruction by fire of the zeppelin LZ 129 Hindenburg just before landing at Lakehurst, New Jersey on 6 May 1937, killing 35 of the 97 people aboard. Previous spectacular airship accidents, from the Wingfoot Express disaster (1919) to the loss of the R101 (1930), the Akron (1933) and the Macon (1935) had already cast doubt on airship safety. The disasters of the U.S. Navy's rigids showed the importance of solely using helium as the lifting medium.[129] Following the destruction of the Hindenburg, the remaining airship making international flights, the Graf Zeppelin was retired (June 1937). Its replacement, the rigid airship Graf Zeppelin II, made a number of flights, primarily over Germany, from 1938 to 1939, but was grounded when Germany began World War II. Both remaining German zeppelins were scrapped in 1940 to supply metal for the German Luftwaffe air force.[130]

Meanwhile, Germany, which was restricted by the Treaty of Versailles in its development of powered aircraft, developed gliding as a sport, especially at the Wasserkuppe, during the 1920s. In its various forms, in the 21st-century sailplane aviation now has over 400,000 participants.[131][132][133]

In 1929, Jimmy Doolittle developed instrument flight.[135]

1929 also saw the first flight of by far the largest plane ever built until then: the Dornier Do X with a wingspan of 48 m. On its 70th test flight on 21 October 1929, there were 169 people on board, a record that was not broken for 20 years.

In 1923, The first successful rotorcraft appeared in the form of the autogyro, invented by Spanish engineer Juan de la Cierva and first flown in 1919. In this design, the rotor is not powered but spins freely as it moves through the air, while a separate engine powers the aircraft to move forward. This was the basis of further development and prototypes that led to the creation of the helicopter. In 1930 Corradino D'Ascanio, an Italian engineer, developed a coaxial helicopter with the important inclusion of three small propellers on the craft, which controlled the pitch, roll, and yaw of the aircraft. Later helicopters saw several adjustments to their rotors but the first modern helicopter was not constructed until 1947 by Igor Sikorsky[136]

Only five years after the German Dornier Do-X had flown, Tupolev designed the largest aircraft of the 1930s era, the Maksim Gorky in the Soviet Union by 1934, as the largest aircraft ever built using the Junkers methods of metal aircraft construction.

In the 1930s, development of the jet engine began in Germany and in Britain and they began testing in 1939 before World War II. The jet engine saw considerable development during the war, with a few jet powered aircraft being used in the war.[137]

After enrolling in the Military Aviation Academy in Eskisehir in 1936 and undertaking training at the First Aircraft Regiment, Sabiha Gökçen, flew fighter and bomber planes becoming the first Turkish, female aviator and the world's first, female, combat pilot. During her flying career, she achieved some 8,000 hours, 32 of which were combat missions.[138][139][140][141]

World War II (1939–1945)

[edit]World War II saw a great increase in the pace of development and production, not only of aircraft but also the associated flight-based weapon delivery systems. Air combat tactics and doctrines took advantage. Large-scale strategic bombing campaigns were launched, fighter escorts introduced and the more flexible aircraft and weapons allowed precise attacks on small targets with dive bombers, fighter-bombers, and ground-attack aircraft. New technologies like radar also allowed more coordinated and controlled deployment of air defence.

The first jet aircraft to fly was the Heinkel He 178 (Germany), flown by Erich Warsitz in 1939, followed by the world's first operational jet aircraft, the Messerschmitt Me 262, in July 1942 and world's first jet-powered bomber, the Arado Ar 234, in June 1943. British developments, like the Gloster Meteor, followed afterwards, but saw only brief use in World War II. The first cruise missile (V-1), the first ballistic missile (V-2), the first (and to date only) operational rocket-powered combat aircraft Me 163—with attained velocities of up to 1,130 km/h (700 mph) in test flights—and the first vertical take-off manned point-defence interceptor, the Bachem Ba 349 Natter, were also developed by Germany. However, jet and rocket aircraft had only limited impact due to their late introduction, fuel shortages, the lack of experienced pilots and the declining war industry of Germany.

Not only aeroplanes, but also helicopters saw rapid development in the Second World War, with the introduction of the Focke Achgelis Fa 223, the Flettner Fl 282 synchropter in 1941 in Germany and the Sikorsky R-4 in 1942 in the USA.

Postwar era (1945–1979)

[edit]

Following World War II, commercial aviation expanded quickly, primarily relying on former military aircraft to carry passengers and cargo. There was an excess of large bombers, such as the B-29 and Lancaster, which were easily converted for commercial use.[142] The DC-3 specifically played a key role, enabling longer and more efficient flights.[142]

The British de Havilland Comet became the first commercial jet airliner and was introduced into scheduled service by 1952. The aircraft was a breakthrough in technical achievements, but had several intense failures. The square design of the windows caused stress cracks from metal fatigue, caused by cycles of cabin pressurization and depressurization.[citation needed] This eventually led to severe structural failures in the fuel area. These issues were resolved too late, since competing jet airliners were already flying. [143]

On September 15, 1956, the USSR’s airline Aeroflot became the first to offer continuous, regular jet services using the Tupolev Tu-104. Soon after, Boeing 707 and DC-8 also set new standards in comfort, safety, and passenger experience. These were the beginning of the Jet Age, the introduction of large-scale commercial air travel. [144]

In October 1947, Chuck Yeager became the first to fly faster than the speed of sound when he piloted the rocket-powered Bell X-1 past the sound barrier. [145] The air speed record for an aircraft was set by the X-15 at 4,534 mph (7,297 km/h) or Mach 6.1 in 1967. This record was later broken by the X-43 in 2004, excluding spacecraft. [146]

Military aircraft had a strategic advantage during the Cold War with the invention of nuclear bombs in 1945. Even just a small fleet of bombers could inflict catastrophic damage, which caused for the development of effective defenses. One early development was supersonic interceptor aircraft. By 1955, the focus shifted toward guided surface-to-air missiles. This eventually led to the emergence of intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBMs), which have nuclear capabilities. An early example of ICBMs occurred in 1957 when the Soviet Union launched Sputnik 1, beginning the Space Race. [147]

In 1961, Yuri Gagarin became the first human in space when he completed a single orbit around Earth in 108 minutes aboard Vostok I. Following this, the United States sent Alan Shepard on a suborbital flight using a Mercury program capsule. In 1963, Canada became the third nation to enter space with the launch of its satellite, Alouette I. The race culminated in the landing on the moon in 1969. [148]

In 1967, the X-15 set the air speed record for an aircraft at 4,534 mph (7,297 km/h) or Mach 6.1. Aside from vehicles designed to fly in outer space, this record was renewed by X-43 in the 21st century.

The Harrier jump jet, capable of vertical landing and takeoff, first flew in 1969. This was also the year of the introduction of the Boeing 747. Additionally, the Aérospatiale-BAC Concorde supersonic passenger airliner had its maiden flight. The Boeing 747 was the largest commercial passenger aircraft ever to fly at the time, now replaced by the Airbus A380, capable of transporting 853 passengers. Aeroflot started flying the Tu-144—the first supersonic passenger plane in 1975. The next year, British Airways and Air France began supersonic flights over the Atlantic. [149]

In 1979, the Gossamer Albatross achieved the status of the first human-powered aircraft to fly over the English channel, which had been a dream for centuries. [150]

Digital age (1980–present)

[edit]

The last quarter of the 20th century saw a change of emphasis. No longer was revolutionary progress made in flight speeds, distances and materials technology. This part of the century instead saw the spreading of the digital revolution both in flight avionics and in aircraft design and manufacturing techniques.

In 1986, Dick Rutan and Jeana Yeager flew an aircraft, the Rutan Voyager, around the world unrefuelled, and without landing. In 1999, Bertrand Piccard became the first person to circle the earth in a balloon.

Digital fly-by-wire systems allow an aircraft to be designed with relaxed static stability. Initially used to increase the manoeuvrability of military aircraft such as the General Dynamics F-16 Fighting Falcon, this is now being used to reduce drag on commercial airliners.

The U.S. Centennial of Flight Commission was established in 1999 to encourage the broadest national and international participation in the celebration of 100 years of powered flight.[151] It publicized and encouraged a number of programmes, projects and events intended to educate people about the history of aviation.

21st century

[edit]21st-century aviation has seen increasing interest in fuel savings and fuel diversification, as well as low cost airlines and facilities. Additionally, much of the developing world that did not have good access to air transport has been steadily adding aircraft and facilities, though severe congestion remains a problem in many up and coming nations. Around 20,000 city pairs[152] are served by commercial aviation, up from less than 10,000 as recently as 1996.

There appears to be newfound interest[153] in returning to the supersonic era whereby waning demand in the turn of the 20th century made flights unprofitable, as well as the final commercial stoppage of the Concorde due to reduced demand following a fatal accident and rising costs.

At the beginning of the 21st century, digital technology allowed subsonic military aviation to begin eliminating the pilot in favour of remotely operated or completely autonomous unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs). In April 2001 the unmanned aircraft Global Hawk flew from Edwards AFB in the US to Australia non-stop and unrefuelled. This is the longest point-to-point flight ever undertaken by an unmanned aircraft and took 23 hours and 23 minutes. In October 2003, the first totally autonomous flight across the Atlantic by a computer-controlled model aircraft occurred. UAVs are now an established feature of modern warfare, carrying out pinpoint attacks under the control of a remote operator.

Major disruptions to air travel in the 21st century included the closing of U.S. airspace due to the September 11 attacks, and the closing of most of European airspace after the 2010 eruption of Eyjafjallajökull.

In 2015, André Borschberg and Bertrand Piccard flew a record distance of 4,481 miles (7,211 km) from Nagoya, Japan to Honolulu, Hawaii in a solar-powered plane, Solar Impulse 2. The flight took nearly five days; during the nights the aircraft used its batteries and the potential energy gained during the day.[154]

On 14 July 2019, Frenchman Franky Zapata attracted worldwide attention when he participated at the Bastille Day military parade riding his invention, a jet-powered Flyboard Air. He subsequently succeeded in crossing the English Channel on his device on 4 August 2019, covering the 35-kilometre (22 mi) journey from Sangatte in northern France to St Margaret's Bay in Kent, UK, in 22 minutes, with a midpoint fueling stop included.[155]

24 July 2019 was the busiest day in aviation, for Flightradar24 recorded a total of over 225,000 flights that day. It includes helicopters, private jets, gliders, sight-seeing flights, as well as personal aircraft. The website has been tracking flights since 2006.[156]

On 10 June 2020, the Pipistrel Velis Electro became the first electric aeroplane to secure a type certificate from EASA.[157]

In the early 21st Century, the first fifth-generation military fighters were produced, starting with the F-22 Raptor and currently Russia, America and China have 5th gen aircraft (2019).[citation needed]

The COVID-19 pandemic had a significant impact on the aviation industry due to the resulting travel restrictions as well as slump in demand among travellers, and may also affect the future of air travel.[158] For example, the mandatory use of face masks on aeroplanes was a common feature of flying in 2020 and 2021.[159]

Mars

[edit]On 19 April 2021, NASA successfully flew its diminutive unmanned helicopter Ingenuity on Mars, humanity's first controlled powered aircraft flight on another planet. The helicopter rose to a height of three metres and hovered in a stable holding position for 30 seconds; a video of the flight was made by its accompanying rover, Perseverance.[160]

Ingenuity, which was initially designed for five demonstration flights, flew 72 times traveling 11 miles in nearly three years. As a homage to all of its aerial predecessors, it carries a postage stamp sized piece of wing fabric from the 1903 Wright Flyer.

Ingenuity's last flight was 18 January 2024, a span of 2 years, 333 days since its first takeoff (the duration in Martian days, or sols, was 1035). Broken and damaged rotor blades suffered during its final landing forced the helicopter's retirement.[161]

See also

[edit]- Aviation archaeology

- Claims to the first powered flight

- List of firsts in aviation

- Timeline of aviation

References

[edit]- ^ a b Crouch, Tom (2004). Wings: A History of Aviation from Kites to the Space Age. New York, New York: W.W. Norton & Co. ISBN 0-393-32620-9.

- ^ Hallion (2003)

- ^ "Flying through the ages" BBC News. Retrieved 2024-10-18.

- ^ "Online Etymology Dictionary | Origin, history and meaning of English words". Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 18 July 2013.

- ^ Cassard, Jean-Christophe; Croix, Alain; Le Quéau, Jean-René; Veillard, Jean-Yves (2008). Dictionnaire d'histoire de Bretagne (in French). Morlaix: Vreizh Skol. p. 77. ISBN 978-2-915623-45-1.

- ^ Wells, H. G. (1961). The Outline of History: Volume 1. Doubleday. p. 153.

- ^ Book of Han, Biography of Wang Mang, 或言能飞, 一日千里, 可窥匈奴.莽辄试之, 取大鸟翮为两翼, 头与身皆著毛, 通引环纽, 飞数百步堕

- ^ a b c Lynn Townsend White, Jr. (Spring, 1961). "Eilmer of Malmesbury, an Eleventh Century Aviator: A Case Study of Technological Innovation, Its Context and Tradition", Technology and Culture 2 (2), pp. 97–111 [101]

- ^ "First Flights". Saudi Aramco World. 15 (1): 8–9. January–February 1964. Archived from the original on 3 May 2008. Retrieved 8 July 2008.

- ^ a b Moolman, Valerie (1980). The road to Kitty Hawk. The Epic of flight. Time-Life Books. Alexandria, Va: Time-Life Books. ISBN 978-0-8094-3260-8.

- ^ Wragg 1974.

- ^ Deng & Wang 2005, p. 122.

- ^ "Amazing Musical Kites". Cambodia Philately. Archived from the original on 13 August 2011. Retrieved 7 January 2014.

- ^ "Kite Flying for Fun and Science" (PDF). The New York Times. 1907. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2 August 2021. Retrieved 14 June 2018.

- ^ Sarak, Sim; Yarin, Cheang (2002). "Khmer Kites". Ministry of Culture and Fine Arts, Cambodia. Archived from the original on 3 May 2015. Retrieved 7 January 2014.

- ^ Needham 1965a, p. 127.

- ^ Hallion (2003) page 9.

- ^ Pelham, D.; The Penguin book of kites, Penguin (1976)

- ^ Leishman, J. Gordon (2006). Principles of Helicopter Aerodynamics. Cambridge aerospace. Vol. 18. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 7–9. ISBN 978-0-521-85860-1. Archived from the original on 13 July 2014.

- ^ Donahue, Topher (2009). Bugaboo Dreams: A Story of Skiers, Helicopters and Mountains. Rocky Mountain Books Ltd. p. 249. ISBN 978-1-897522-11-0.

- ^ Wragg 1974, p. 10.

- ^ Deng & Wang 2005, p. 113.

- ^ Ege 1973, p. 6.

- ^ Wragg 1974, p. 11.

- ^ a b c d e Wallace, Robert (1972) [1966]. The World of Leonardo: 1452–1519. New York: Time-Life Books. p. 102.

- ^ a b Durant, Will (2001). Heroes of History: A Brief History of Civilization from Ancient Times to the Dawn of the Modern Age. New York: Simon & Schuster. p. 209. ISBN 978-0-7432-2612-7. OCLC 869434122. Archived from the original on 7 March 2024. Retrieved 18 January 2021.

- ^ Da Vinci, Leonardo (1971). Taylor, Pamela (ed.). The Notebooks of Leonardo da Vinci. New American eLibrary. p. 107.

- ^ Fairlie & Cayley 1965, p. 163.

- ^ Popham, A.E. (1947). The drawings of Leonardo da Vinci (2nd ed.). Jonathan Cape.

- ^ "Francesco Lana-Terzi, S.J." web.archive.org. 24 April 2021. Retrieved 21 November 2024.

- ^ Louro, F.V.; Melo De Sousa, Joao M. (10 January 2014). "Father Bartholomeu Lourenço de Gusmão: a Charlatan or the First Practical Pioneer of Aeronautics in History". 52nd Aerospace Sciences Meeting. Reston, Virginia: American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics. doi:10.2514/6.2014-0282.

- ^ texte, Compagnie générale maritime Auteur du (23 December 1930). "L'Atlantique : journal quotidien paraissant à bord des paquebots de la Compagnie générale transatlantique : dernières nouvelles reçues par télégraphie sans fil". Gallica. Retrieved 21 November 2024.

- ^ a b Gillispie, Charles Coulston (1983). The Montgolfier brothers and the invention of aviation, 1783-1784: with a word on the importance of ballooning for the science of heat and the art of building railroads. Princeton, N.J: Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-08321-6.

- ^ "Early Balloon Flight in Europe". web.archive.org. 2 June 2008. Retrieved 21 November 2024.

- ^ Gillispie, Charles Coulston (1983). The Montgolfier brothers and the invention of aviation, 1783-1784: with a word on the importance of ballooning for the science of heat and the art of building railroads. Princeton, N.J: Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-08321-6.

- ^ Walker (1971) Volume I, Page 195.

- ^ Winter, Frank H. (1992). "Who First Flew in a Rocket?", Journal of the British Interplanetary Society 45 (July 1992), p. 275-80

- ^ Harding, John (2006), Flying's strangest moments: extraordinary but true stories from over one thousand years of aviation history, Robson Publishing, p. 5, ISBN 1-86105-934-5

- ^ Needham, Joseph (1965). Science and Civilisation in China. Vol. IV (part 2). p. 591. ISBN 978-0-521-05803-2.

- ^ Harrison, James Pinckney (2000). Mastering the Sky. Da Capo Press. p. 27. ISBN 978-1-885119-68-1.

- ^ Qtd. in O'Conner, Patricia T. (17 November 1985). "In Short: Nonfiction; Man Was Meant to Fly, But Not at First". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 15 June 2013. Retrieved 24 May 2009.

- ^ "Burattini's Flying Dragon". Flight International. 9 May 1963. Archived from the original on 19 August 2016.

- ^ Hart, Clive (4 July 2016). "Swedenborg's flying saucer". The Aeronautical Journal. 84 (836): 282–284.

- ^ "American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics – History – Spain". Aiaa.org. 22 April 2019. Archived from the original on 10 November 2016. Retrieved 22 April 2019.

- ^ "Premier vol humain - Angoulême 1801 | Aérostèles". www.aerosteles.net (in French). Archived from the original on 4 June 2023. Retrieved 14 February 2023.

- ^ Didion, Isidor (1 September 1837). "Rapport sur la plus grande vitesse que l'on peut obtenir par la navigation aérienne". Gallica.bnf.fr (in French). Congrès scientifique de France, 5th Session, Metz. Archived from the original on 14 February 2023. Retrieved 14 February 2023. He answered to the 12th and last question Archived 22 October 2018 at the Wayback Machine of the congress: "Will it be possible to improve the aerostatic art, by a better combination of means used until now, in order to leave up aerostats and conduct them", thus showing the interest of the scientists of that time (first half of the 19th) century on that question.

- ^ Fairlie & Cayley 1965, p. 158.

- ^ "Aviation History". Archived from the original on 13 April 2009. Retrieved 26 July 2009.

In 1799 he set forth for the first time in history the concept of the modern aeroplane. Cayley had identified the drag vector (parallel to the flow) and the lift vector (perpendicular to the flow).

- ^ "Sir George Cayley (British Inventor and Scientist)". Britannica. Archived from the original on 23 July 2012. Retrieved 26 July 2009.

English pioneer of aerial navigation and aeronautical engineering and designer of the first successful glider to carry a human being aloft. Cayley established the modern configuration of an aeroplane as a fixed-wing flying machine with separate systems for lift, propulsion, and control as early as 1799.

- ^ Gibbs-Smith 2003, p. 35

- ^ Wragg 1974, p. 60.

- ^ Angelucci & Matricardi 1977, p. 14.

- ^ Pritchard, J. Laurence. Summary of First Cayley Memorial Lecture at the Brough Branch of the Royal Aeronautical Society Archived 17 August 2016 at the Wayback Machine Flight number 2390 volume 66 page 702, 12 November 1954. Retrieved: 29 May 2010. "In thinking of how to construct the lightest possible wheel for aerial navigation cars, an entirely new mode of manufacturing this most useful part of locomotive machines occurred to me: vide, to do away with wooden spokes altogether, and refer the whole firmness of the wheel to the strength of the rim only, by the intervention of tight cording."

- ^ Pettigrew, James Bell (1911). . In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 10 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 502–519.

- ^ Jarrett 2002, p. 53.

- ^ Stokes 2002, pp. 163–166, 167–168.

- ^ Scientific American. Munn & Company. 13 March 1869. p. 169. Archived from the original on 7 March 2024. Retrieved 20 October 2021.

- ^ "John Stringfellow". Flying Machines. Archived from the original on 28 February 2018. Retrieved 4 March 2018.

- ^ Parramore, Thomas C. (1 March 2003). First to Fly: North Carolina and the Beginnings of Aviation. UNC Press Books. p. 46. ISBN 978-0-8078-5470-9. Archived from the original on 17 May 2023. Retrieved 6 April 2023.

- ^ "High hopes for replica plane". BBC News. 10 October 2001. Archived from the original on 15 March 2007. Retrieved 4 March 2018.

- ^ Magoun, F. Alexander; Hodgins, Eric (1931). A History of Aircraft. Whittlesey House. p. 308.