Hugh Franklin (suffragist)

Hugh Arthur Franklin | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 27 May 1889 Kensington, London, England |

| Died | 21 October 1962 (aged 73) |

| Nationality | British |

| Other names | Henry Forster (alias as fugitive)[1] |

| Education |

|

| Organization | Women's Social and Political Union |

| Known for | Activism for women's suffrage |

| Political party | Labour Party |

| Spouses |

|

| Father | Arthur Ellis Franklin |

| Relatives |

|

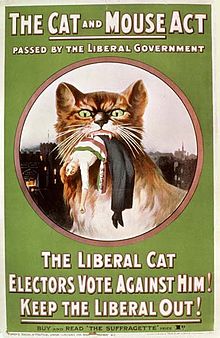

Hugh Arthur Franklin (27 May 1889 – 21 October 1962)[1] was a British suffragist and politician. Born into a wealthy Anglo-Jewish family, he rejected both his religious and social upbringing to protest for women's suffrage. Joining in with the militant suffragettes, he was sent to prison multiple times, making him one of the few men to be imprisoned for his part in the suffrage movement.[2] His crimes included an attempted attack on Winston Churchill and an act of arson on a train.[3] He was the first person to be released under the Prisoners (Temporary Discharge for Ill Health) Act 1913 (the so-called "Cat and Mouse law"), and he later married the second, Elsie Duval.[4] Following his release, he never returned to prison, but still campaigned for women's rights and penal reform. He stood unsuccessfully for parliament on two occasions, but did win a seat on Middlesex County Council and was a member of the Labour Party executive committee.[1]

Early life

[edit]Hugh Franklin was born to Arthur Ellis Franklin and Caroline Franklin (née Jacob), the fourth of six children.[5] The Franklin family was a prominent member of the Anglo-Jewish "cousinhood", and the family was well-off and well-connected.[6] Hugh's uncles included the Liberal politicians Sir Leonard Franklin, Sir Stuart Samuel and Herbert Samuel, 1st Viscount Samuel.[1][7]

Hugh was educated at Clifton College[8] and, on graduation in 1908, he moved to Gonville and Caius College, Cambridge to read engineering. However, on finishing his first year of study, Hugh made several moves that would ultimately lead to his estrangement from his father. Firstly, he wrote his father a letter, declaring his agnosticism and rejecting the Jewish faith. Secondly, he attended a speech by Emmeline Pankhurst and her daughter Christabel on the topic of women's suffrage. Finally, he abandoned his studies in engineering and began to read economics and sociology instead. He became an active member of the Women's Social and Political Union, the Young Purple White and Green Club and the Men’s Political Union for Women’s Enfranchisement. Hugh left Cambridge for a while to promote the WSPU in London – on his return, he did not put his heart into his studies and missed his examinations. By June 1910, he had abandoned university altogether.[3]

Although his religious views had led his father to disown him, the family ties were still strong enough that Herbert Samuel, at that point Postmaster General, decided to offer Hugh a position as a private secretary to Matthew Nathan, Secretary of the General Post Office. Hugh took the position reluctantly. It was not to last long, however.[1]

Activism

[edit]

Hugh was one of the people present at the rally on Parliament on 18 November 1910 – the rally that was later to be known as Black Friday.[1] When the Conciliation Bill, which would have granted limited suffrage to female property owners, failed to pass, around 300 suffragettes descended on the Palace of Westminster. The protesters were driven back by police, and many reported being victims of police brutality.[9]

Winston Churchill was at that point Home Secretary, and he was widely blamed for the police excesses on display. Hugh Franklin, who was angered by what he had seen, began to follow Churchill to heckle him at public meetings. On the train back from a meeting in Bradford, Yorkshire,[10] Hugh met Churchill and set on him with a dog whip, shouting "Take this, you cur, for the treatment of the suffragists!"[1]

The attack was widely reported, even reaching the headlines of The Times, and for the Franklin family, it was a great embarrassment.[6] Hugh was imprisoned for six weeks and dismissed as Sir Nathan's secretary. In March 1911, he was sentenced for another month for throwing rocks at Churchill's house. Hugh took part in the hunger strikes that were then being waged by the suffragettes, and was force fed repeatedly during his imprisonment. The force feeding turned him into an activist for penal reform – not long after he was released, he began petitioning his uncle to investigate the case of William Ball, a prisoner supposedly driven insane by force feeding.[1][11]

Hugh's final militant act was setting fire to a railway carriage at Harrow on 25 October 1912. He then went on the run, spending two months at the famous radical book store Henderson's, better known as "The Bomb Shop", before being caught and sentenced to six months in prison in February 1913.[3] He was force fed 114 times, and the ordeal left him so weak that he was released as soon as the Prisoners (Temporary Discharge for Ill Health) Act 1913 came into force, making him the first person to be let out under the act.[4]

With his licence expiring in May,[12] he fled the country and stayed in Brussels under the assumed name of Henry Forster until the outbreak of World War I. Due to poor eyesight, he was not called to military service. He took a job in a munitions factory and after the war he ceased his militant activities, although he kept close ties with the suffragettes, including Sylvia Pankhurst.[3]

Later life

[edit]Hugh joined the Labour Party in 1931 and attempted to become an MP, standing in Hornsey in 1931 and St Albans in 1935. Despite his lack of success here, he was prolific in local politics, and eventually won a seat on Middlesex County Council, and he was ultimately able to join the Labour Party National Executive Committee. He died on 21 October 1962.[1][3]

Family and relationships

[edit]

Hugh was the fourth of six siblings and had three brothers and two sisters; in order, Jacob, Alice, Cecil, Helen and Ellis.[5] Hugh was not the only politically active one – Alice, a staunch socialist, would later become a leader of the Townswomen's Guild; Helen became forewoman at the Royal Arsenal, where she was forced to resign for supporting female workers and attempting to form a trade union, and Ellis became vice-principal of the Working Men's College. Through Ellis, Hugh was also the uncle of the famous crystallographer Rosalind Franklin.[6]

In 1915, Hugh married fellow suffragist Elsie Diederichs Duval (1893–1919), who he had been engaged to since their "Cat and Mouse" days in 1913 – Elsie was the second person to be released under the law, after Hugh.[13] Elsie converted to Judaism, and the couple married in the synagogue. Her mother Jane Emily née Hayes (c.1861–1924) was an active suffragette, as Emily Hayes Duval she was imprisoned for six weeks in 1908 following a demonstration at H. H. Asquith's house.

Hugh stayed with Elsie until, probably weakened by her own force feeding, she died in 1919 from Spanish flu.[13] Hugh later married another non-Jewish Elsie in 1921, Elsie Constance Tuke. Tuke never converted to Judaism. This was the final straw for Arthur, who disinherited him.[6]

Brian Harrison recorded an oral history interview with Hugh's nephew, Norman Franklin (along with his wife Jill), in September 1979, as part of the Suffrage Interviews project, titled Oral evidence on the suffragette and suffragist movements: the Brian Harrison interviews[14]. The first section of the interview centres around Hugh, including his activities for the suffrage movement, his lifestyle and the failure of his business. Another nephew, Colin Franklin (and his wife, Charlotte), were interviewed in June 1977, and their niece, Mrs Ursula Richley (and her husband Noel), were interviewed in September 1977. These interviews have a greater focus on Alice Franklin, but provide further information about Hugh, such as his life and career following his suffrage campaigning, his work for the Metropolitan Water Board during the Second World War, and his family relationships.

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h i "Franklin, Hugh (1889–1962); suffragist". The Women's Library (London School of Economics). Archived from the original on 2 August 2013. Retrieved 7 November 2015.

- ^ Mary Stott (1978). Organization woman: the story of the National Union of Townswomen's Guilds. Heinemann. p. 13. ISBN 0434748005.

- ^ a b c d e Elizabeth Crawford (2013). "Hugh Franklin". Women's Suffrage Movement. Routledge. pp. 228–230. ISBN 978-1135434021.

- ^ a b June Balshaw (2004). "More than Just 'a Sporting Couple': the Letters of a Militant Marriage". Gender and Politics in the Age of Letter Writing, 1750–2000. Ashgate. p. 193. ISBN 0754638510.

- ^ a b Arthur Ellis Franklin (1913). Records of the Franklin family and collaterals. p. 54. Retrieved 2 August 2013.

- ^ a b c d Brenda Maddox (2002). Rosalind Franklin – The Dark Lady of DNA. Harper Collins. ISBN 0060985089.

- ^ Bernard Wasserstein, 'Samuel, Herbert Louis, first Viscount Samuel (1870–1963)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004; online edn, May 2011 accessed 2 Aug 2013

- ^ "Clifton College Register" Muirhead, J.A.O. p248: Bristol; J.W Arrowsmith for Old Cliftonian Society; April 1948

- ^ Paula Bartley (2007). Access to History: Votes for Women. Hodder Education. p. unnumbered page. ISBN 978-1444155372.

- ^ "Catalogue".

- ^ Stanley Holton (2002). Suffrage Days. Taylor & Francis. p. 178. ISBN 0203427564.

- ^ "Three Absconders". The West Australian. 16 May 1913. p. 7.

- ^ a b Elizabeth Crawford (2013). "Elsie Duval". Women's Suffrage Movement. Routledge. pp. 179–180. ISBN 978-1135434021.

- ^ London School of Economics and Political Science. "The Suffrage Interviews". London School of Economics and Political Science. Retrieved 22 April 2024.

- 1889 births

- 1962 deaths

- Alumni of Gonville and Caius College, Cambridge

- British Jews

- British suffragists

- British women's rights activists

- Councillors in Greater London

- English agnostics

- Franklin family (Anglo-Jewish)

- Jewish agnostics

- Jewish feminists

- Jewish socialists

- Labour Party (UK) councillors

- Labour Party (UK) parliamentary candidates

- British male feminists

- British feminists

- Members of the Fabian Society

- People educated at Clifton College

- Jewish suffragists

- Members of the Men's League for Women's Suffrage (United Kingdom)