Horse stance

This article needs additional citations for verification. (March 2022) |

| Horse Stance | |||

|---|---|---|---|

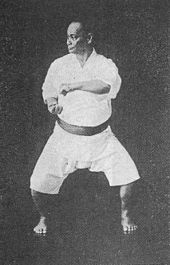

A horse stance in wushu | |||

| Chinese name | |||

| Traditional Chinese | 馬步 | ||

| |||

| Korean name | |||

| Hangul | 안운서기 | ||

| Japanese name | |||

| Kanji | 騎馬立ち | ||

The horse stance is a common posture in Asian martial arts.[1] It is called mǎbù (馬步) in Chinese, kiba-dachi (騎馬立ち) in Japanese, and juchum seogi (주춤 서기)[2] or annun seogi (lit. sitting stance) in Korean. This stance can not only be integrated into fighting but also during exercises and forms. It is most commonly used for practicing punches or to strengthen the legs and back.[3] The modified form of horse stance, in which heels are raised, is a fighting stance in International Karate Tournaments.[4] The Chinese form of horse stance is a fighting stance which changes into front stance while using hip rotation to develop punching force.[5]

Chinese martial arts

[edit]Mabu is used for endurance training as well as strengthening the back and leg muscles, tendon strength, and overall feeling and understanding of "feeling grounded". It is a wide, stable stance with a low center of gravity.[6] Feet are placed 45 degree outward .[7]

Northern styles

[edit]The ideal horse stance in most northern Chinese martial arts (such as Mizongquan and Chaquan) will have the feet pointed forward, thighs parallel to the floor, with the buttocks pushed out, and the back "arched up" to keep the upper body from leaning forward. The emphasis on this latter point will vary from school to school as some schools of Long Fist, such as Taizu and Bajiquan, will opt for the hips forward, with the buttocks "tucked in."[8]

In Northern Shaolin, the distance between the feet is approximately two shoulder widths apart.

Southern Shaolin

[edit]Southern Chinese martial arts usually pronounce horse stance by its Cantonese pronunciation of "Sei Ping Ma".[9][10] In Southern Shaolin, a wide horse stance is assumed as if riding a horse. Such low postures strengthen the legs of the practitioner. The horse stance in southern Chinese systems is commonly done with the thighs parallel to the ground and the toes pointing forward or angled slightly out.

Southern Chinese styles (such as Hung Gar) are known for their deep and wide horse stance.[11]

See also Wushu Stances for more information.

Japanese martial arts

[edit]

In Japanese martial arts, the horse stance (kiba-dachi) has many minor variations between individual schools, including the distance between the feet, and the height of the stance.[12][13] One constant feature is that the feet must be parallel to each other.[14]

Note that the horse stance differs from the straddle stance (四股立ち, shiko-dachi), widely used in sumo, in which the feet point outward at 45 degrees rather than being parallel.[15]

Indian martial arts

[edit]

What is referred to as the horse stance in south Indian martial arts is very different from the posture of the same name in other Asian fighting styles.[16] Known in Malayalam as aswa vadivu or ashwa vadivu, it imitates the horse itself rather than the rider.[17] In kalaripayat, the horse stance has the hind leg stretched completely backward while the knee of the front leg is bent ninety degrees. The horse stance is the main posture of the Shiva form and is related to the virabhadrasana (warrior pose) in yoga.[18][19]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ The Whirling Circles of Ba Gua Zhang: The Art and Legends of the Eight Trigram Palm. Blue Snake Books. 26 June 2007. ISBN 9781583941898.

- ^ Sekwondo: World Taekwondo Federation Taekwondo Initiation for Novices over the Age of Forty. A Didactical Guide for Trainers and Students. Strategic Book. 11 May 2012. ISBN 9781622121175.

- ^ Shaolin Nei Jin Qi Gong: Ancient Healing in the Modern World. Weiser Books. January 1996. ISBN 9780877288763.

- ^ Norris, Chuck (1975). Winning Tournament Karate. Black Belt Communications. ISBN 978-0-89750-016-6.

- ^ Morris, Neil (2001). Kung Fu. Heinemann Library. ISBN 978-0-431-11043-1.

- ^ Fan Chin-Na the art of Countergrips. Igor Dudukchan. 30 November 2016.

- ^ Morris, Neil (2001). Kung Fu. Heinemann Library. ISBN 978-0-431-11043-1.

- ^ Falk's Dictionary of Chinese Martial Arts, Deluxe Soft Cover. Lulu.com. 11 June 2019. ISBN 9780987902856.

- ^ Complete Wing Chun: The Definitive Guide to Wing Chun's History and Traditions. Tuttle. 3 November 2015. ISBN 9781462917532.

- ^ "Black Belt". January 1984.

- ^ "Black Belt". November 1981.

- ^ "Black Belt". December 1982.

- ^ "Black Belt". February 1996.

- ^ Bo, Karate Weapon of Self-defense. Black Belt Communications. 1976. ISBN 9780897500197.

- ^ Okinawa Goju Ryu. Lulu.com. ISBN 9781458342867.

- ^ Shadows of the Prophet: Martial Arts and Sufi Mysticism. Springer. 5 June 2009. ISBN 9781402093562.

- ^ Kalarippayat. Lulu.com. 25 September 2008. ISBN 9781409226260.

- ^ "Yoga Journal".

- ^ "Yoga Journal".

External links

[edit]- Horse Stance Demo Horse stance demonstration

- Kalari Animal Posture - Horse Horse stance of kalaripayat

- Southern Shaolin Horse Stance - correct technique and training program Southern Shaolin Horse Stance - correct technique and training program