History of psychotherapy

| Part of a series on |

| Mental health |

|---|

| Treated by |

| Studied by |

| Society |

| History |

| By country |

| Part of |

Although modern, scientific psychology is often dated from the 1879 opening of the first psychological clinic by Wilhelm Wundt, attempts to create methods for assessing and treating mental distress existed long before. The earliest recorded approaches were a combination of religious, magical and/or medical perspectives.[1] Early examples of such psychological thinkers included Patañjali, Padmasambhava,[2] Rhazes, Avicenna[3] and Rumi.[4]

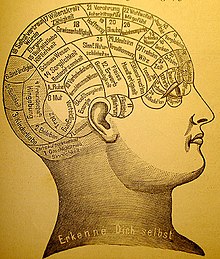

In an informal sense, psychotherapy can be said to have been practiced through the ages, as individuals received psychological counsel and reassurance from others. In the 19th century, one could have ones head examined, literally, using phrenology, the study of the shape of the skull developed by respected anatomist Franz Joseph Gall. Other popular treatments included physiognomy—the study of the shape of the face—and mesmerism, developed by Franz Anton Mesmer—designed to relieve psychological distress by the use of magnets. Spiritualism and Phineas Quimby's "mental healing" technique that was very like modern concept of "positive visualization" were also popular. By 1832 psychotherapy made its first appearance in fiction with a short story by John Neal titled "The Haunted Man."[5]

While the scientific community eventually came to reject all of these methods, academic psychologists also were not concerned with serious forms of mental illness. That area was already being addressed by the developing fields of psychiatry and neurology within the asylum movement and the use of moral therapy.[1] It wasn't until the end of the 19th century, around the time when Sigmund Freud was first developing his "talking cure" in Vienna, that the first scientifically clinical application of psychology began—at the University of Pennsylvania, to help children with learning disabilities.

Although clinical psychologists originally focused on psychological assessment, the practice of psychotherapy, once the sole domain of psychiatrists, became integrated into the profession after the Second World War.[6] Psychotherapy began with the practice of psychoanalysis, the "talking cure" developed by Sigmund Freud. Soon afterwards, theorists such as Alfred Adler and Carl Jung began to introduce new conceptions about psychological functioning and change. These and many other theorists helped to develop the general orientation now called psychodynamic therapy, which includes the various therapies based on Freud's essential principle of making the unconscious conscious.

In the 1920s, behaviorism became the dominant paradigm, and remained so until the 1950s. Behaviorism used techniques based on theories of operant conditioning, classical conditioning and social learning theory. Major contributors included Joseph Wolpe, Hans Eysenck, and B.F. Skinner. Because behaviorism denied or ignored internal mental activity, this period represents a general slowing of advancement within the field of psychotherapy.[7]

Wilhelm Reich began to develop body psychotherapy in the 1930s.[citation needed]

Starting in the 1950s, two main orientations evolved independently in response to behaviorism—cognitivism and existential-humanistic therapy.[8] The humanistic movement largely developed from both the Existential theories of writers like Rollo May and Viktor Frankl (a less well known figure Eugene Heimler[9]) and the Person-centered psychotherapy of Carl Rogers. These orientations all focused less on the unconscious and more on promoting positive, holistic change through the development of a supportive, genuine, and empathic therapeutic relationship. Rollo May, Carl Rogers, and Irvin Yalom acknowledge the influence of Otto Rank (1884–1939), Freud's acolyte, then critic.

During the 1950s, Albert Ellis developed the first form of cognitive behavioral therapy, Rational Emotive Behavior Therapy (REBT) and few years later Aaron T. Beck developed cognitive therapy. Both of these included therapy aimed at changing a person's beliefs, by contrast with the insight-based approach of psychodynamic therapies or the newer relational approach of humanistic therapies. Cognitive and behavioral approaches were combined during the 1970s, resulting in Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT).[8] Being oriented towards symptom-relief, collaborative empiricism and modifying core beliefs, this approach has gained widespread acceptance as a primary treatment for numerous disorders.

Since the 1970s, other major perspectives have been developed and adopted within the field. Perhaps the two biggest have been Systems Therapy and Transpersonal psychology. Systems therapy focuses on family and group dynamics, whereas Transpersonal psychology focuses on the spiritual facet of human experience. Other important orientations developed in the last three decades include Feminist therapy, Somatic Psychology, Expressive therapy, and applied Positive psychology. Clinical psychology in Japan developed towards a more integrative socially-orientated counseling methodology. Practice in India developed from both traditional metaphysical and ayurvedic systems and Western methodologies.[10]

Since 1993, the American Psychological Association Division 12 Task Force has created and revised a list of empirically supported psychological treatments for specific disorders.[11][12][13] The Division 12 standards are based on 7 "essential" criteria for research quality, such as randomization and the use of validated psychological assessments.[14] In general, cognitive behavioral treatments for psychological disorders have received greater support than other psychotherapeutic approaches. Passionate debate among clinical scientists and practitioners about the superiority of evidence-based practices is ongoing,[15] and some have presented correlational data that indicate that most of the major therapies are about of equal effectiveness and that the therapist, client, and therapeutic alliance account for a larger portion of client improvement from psychotherapy.[16][17] While many Ph.D. training programs in clinical psychology have taken a strong empirical approach to psychotherapy that has led to a greater emphasis on cognitive behavioral interventions, other training programs and psychologists are now adopting an eclectic orientation. This integrative movement attempts to combine the most effective aspects of all the schools of practice.

See also

[edit]- Abnormal psychology

- Clinical psychology

- History of psychoanalysis

- Mental health

- Psychiatry

- History of psychology

- History of psychiatry

References

[edit]- ^ a b Benjamin, Ludy. (2007). A Brief History of Modern Psychology. Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4051-3206-0

- ^ T. Clifford and Samuel Wiser (1984), Tibetan buddhist medicine and psychiatry

- ^ Afzal Iqbal and A. J. Arberry, The Life and Work of Jalaluddin Rumi, p. 94.

- ^ Rumi (1995) cited in Zokav (2001), p.47.

- ^ Sears, Donald A. (1978). John Neal. Boston, Massachusetts: Twayne Publishers. p. 95. ISBN 080-5-7723-08.

- ^ Buchanan, Roderick D. (2003). "Legislative warriors: American psychiatrists, psychologists, and competing claims over psychotherapy in the 1950s". Journal of the History of the Behavioral Sciences. 39 (3): 225–49. doi:10.1002/jhbs.10113. PMID 12891691.

- ^ Alessandri, M., Heiden, L., & Dunbar-Welter, M. (1995). "History and Overview" in Heiden, Lynda & Hersen, Michel (eds.), Introduction to Clinical Psychology. New York : Plenum Press. ISBN 0-306-44877-7

- ^ a b Reisman, John. (1991). A History of Clinical Psychology. UK : Taylor Francis. ISBN 1-56032-188-1

- ^ Coppock, Vicki; Hopton, John (2002-01-04). Critical Perspectives on Mental Health. Routledge. ISBN 9781135358426.

- ^ Hall, John & Llewelyn, Susan. (2006). What is Clinical Psychology? 4th Edition. UK: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-856689-1

- ^ Chambless D. L.; Hollon S. D. (1998). "Defining empirically supported therapies". Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 66 (1): 7–18. doi:10.1037/0022-006x.66.1.7. PMID 9489259.

- ^ Chambless D. L.; Sanderson W. C.; Shoham V.; Bennett Johnson S.; Pope K. S.; Crits-Christoph P.; Baker M.; Johnson B.; Woody S. R.; Sue S.; Beautler L.; Williams D. A.; McCurry S. (1996). "An update on empirically validated therapies". Clinical Psychologist. 49: 5–18.

- ^ Chambless D.; Baker M. J.; Baucom D. H.; Beutler L. E.; Calhoun K. S.; Crits-Christoph P.; Daiuto A.; DeRubeis R.; Detweiler J.; Haaga D. A. F.; Johnson S. B.; McCurry S.; Mueser K. T.; Pope K. S.; Sanderson W.; Shoham V.; Stickle T.; Williams D. A.; Woody S. R. (1998). "Update on empirically validated therapies: II". Clinical Psychologist. 51: 3–16.

- ^ Church D.; Feinstein D.; Palmer-Hoffman J.; Stein P. K.; Tranguch A. (2014). "Empirically supported psychological treatments: The challenge of evaluating clinical innovations". Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. 202 (10): 699–709. doi:10.1097/NMD.0000000000000188. PMID 25265265. S2CID 24176625.

- ^ Wampold, B. E. Ollendick, T. H. King, N. J. (2006). Do therapies designated as empirically supported treatments for specific disorders produce outcomes superior to non-empirically supported treatment therapies? In J.C. Norcross L.E. Beutler R.F. Levant (Eds.), Evidence-based practices in mental health: Debate and dialogue on the fundamental issues (pp. 299–328). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

- ^ Leichsenring Falk; Leibing Eric (2003). "The effectiveness of psychodynamic therapy and cognitive behavior therapy in the treatment of personality disorders: A meta-analysis". The American Journal of Psychiatry. 160 (7): 1223–1233. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.160.7.1223. PMID 12832233.

- ^ Reisner Andrew (2005). "The common factors, empirically validated treatments, and recovery models of therapeutic change". The Psychological Record. 55 (3): 377–400. doi:10.1007/BF03395517. S2CID 142840311. Archived from the original on 2020-08-06. Retrieved 2019-08-17.

Further reading

[edit]- Henri Ellenberger: The Discovery of the Unconscious: The History and Evolution of Dynamic Psychiatry, Basic Books, 1981

- Eva Illouz: Saving the Modern Soul: Therapy, Emotions, and the Culture of Self-Help, University of California Press 2008, ISBN 0-520-25373-6

- Renato Foschi & Marco Innamorati: A Critical History of Psychotherapy. Volume 1: From Ancient Origins to the Mid 20th Century, Routledge 2022, ISBN 978-1032169408

- Renato Foschi & Marco Innamorati: A Critical History of Psychotherapy. Volume 2: From the Mid-20th to the 21st Century, Routledge 2022, ISBN 978-1032169415