History of Texas A&M University

The history of Texas A&M University, the first public institution of higher education in Texas, began in 1871, when the Agricultural and Mechanical College of Texas was established as a land-grant college by the Reconstruction-era Texas Legislature. Classes began on October 4, 1876. Although Texas A&M was originally scheduled to be established under the Texas Constitution as a branch of the yet-to-be-created University of Texas, subsequent acts of the Texas Legislature never gave the university any authority over Texas A&M. In 1875, the Legislature separated the administrations of A&M and the University of Texas, which still existed only on paper.

For much of its first century, enrollment at Texas A&M was restricted to men who were willing to participate in the Corps of Cadets and receive military training. During this time, a limited number of women were allowed to attend classes but forbidden from gaining a degree. During World War I, 49% of A&M graduates were in military service, and in 1918, the senior class was mustered into military service to fight in France. During World War II, Texas A&M produced over 20,000 combat troops, contributing more officers than both the United States Military Academy and United States Naval Academy combined.

Shortly after World War II, the Texas Legislature redefined Texas A&M as a university and the flagship school of the Texas A&M University System, making official the school's status as a clear and separate institution from the University of Texas. In the 1960s, the state legislature renamed the school Texas A&M University, with the "A&M" becoming purely symbolic. Under the leadership of James Earl Rudder, the school became racially integrated and coeducational. Membership in the Corps of Cadets became voluntary.

In the second half of the 20th century, the university was recognized for its research with the designations sea-grant university and space-grant university. The school was further honored in 1997 with the establishment of the George Bush Presidential Library on the western edge of the campus.

Early years

[edit]

The United States Congress laid the groundwork for the establishment of Texas A&M with their proposal of the Morrill Act. The Morrill Act, signed into law July 2, 1862, was created to enable states to establish colleges with the following tenet which may be found in Section 5 of the legislation:[1]

...leading object shall be, without excluding other scientific and classical studies and including military tactics, to teach such branches of learning as are related to agriculture and mechanical arts ... in order to promote the liberal and practical education of the industrial classes in the several pursuits and professions in life...

The Morrill Act did not specify the extent of military training, leading many land-grant schools to provide only minimal training, Texas A&M was an exception. The only mention of military training is in Section 5.[1] The military tradition of Texas A&M was greatly influenced during the first four administrations with the presence of four alumnus of the Virginia Military Institute; Robert Page Waller Morris, John Garland James, Hardaway Hunt Dinwiddie and John Waller Clark.[2]

States were granted public lands be sold at auctions to establish a permanent fund to support the schools. Both the Republic of Texas and the Texas State Legislature also set aside public lands for a future college.[3] The Agricultural and Mechanical College of Texas, known as Texas A.M.C., was established by the state legislature on April 17, 1871, as the state's first public institution of higher education.[4] The legislature provided US$75,000 for the construction of buildings at the new school, and state leaders invested profits from the sale of 180,000 acres (730 km2) received under the Land-Grant College Act in gold frontier defense bonds, creating a permanent endowment for the college. A committee tasked with finding a home for the new college chose Brazos County, which agreed to donate 2,416 acres (10 km2) of land.[3] Jefferson Davis, former President of the Confederate States of America, was offered the presidency of the college but turned it down.[5] He recommended Thomas S. Gathright, who was the Mississippi Superintendent of Public Instruction, instead. Gathright was the first president of the college.[6]

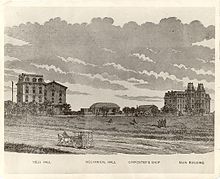

The college officially opened on October 4, 1876, with six professors. Forty students were present on the first day of classes, but by the end of the school year the number had grown to 106 students. Only men were admitted, and all students were required to participate in the Corps of Cadets and receive military training. The campus bore minimal resemblance to its modern counterpart. Wild animals roamed freely around the campus, and the area served as a meeting point for the Great Western Cattle Trail.[7]

Despite its name, the college taught no classes in agriculture, instead concentrating on classical studies, languages, literature, and applied mathematics. After four years, students could attain degrees in scientific agriculture, civil and mining engineering, and language and literature.[8] Local farmers complained that the college was abusing its mission, and, in November 1879, the president and faculty were replaced and given a mandated curriculum in agriculture and engineering.[3]

During these early years, student life was molded by the Corps of Cadets. The Corps was divided into a battalion of three companies, and rivalry among the companies was strong, giving birth to the Aggie spirit and future traditions. No bonfires, yell practices, or athletics teams existed as yet, and social clubs and fraternities were discouraged.[9]

Enrollment, which had climbed as high as 500 students, declined to only 80 students in 1883, the year the University of Texas opened in Austin, Texas. Although the Texas Constitution specified that the Agricultural and Mechanical College was to be a branch of a proposed University of Texas,[4] the Austin school was established with a separate board of regents. Texas A.M.C. continued to be governed by its own board of directors.[3]

The two Texas schools quickly began to battle over the limited funds that the state legislature made available for higher education. In 1887, the Texas Agricultural Experiment Station was established at Texas A.M.C., enabling the college to gain more funding.[3] Many residents of the state saw little need for two colleges in Texas, and some wanted to close the agricultural and mechanical school.[10]

Sul Ross era

[edit]

Texas A.M.C. president Lawrence Sullivan Ross, known affectionately to students as "Sully", is credited for saving the school from closure and transforming it into a respected military institution.[10] Ross, the immediate past governor of Texas, had been a well-respected Confederate Brigadier General and enjoyed a good reputation among state residents.[3]

When Ross arrived at the school, he found no running water, a housing shortage, a disgruntled faculty, and many students running wild. As Ross began to make improvements, parents began to send their children to the school in the hopes that they would learn from Ross's example.[10] Although enrollment had always been limited to men, in 1893, Ethel Hudson, the daughter of an A&M professor, became the first woman to attend classes at the school and helped edit the annual yearbook. She was made an honorary member of the class of 1895. Several years later her twin sisters became honorary members of the class of 1903, and slowly other daughters of Aggie professors were allowed to attend classes.[11]

Under Ross's seven and one-half year tenure, many enduring Aggie traditions formed. These traditions include the first Aggie Ring, the first yearbook, and the formation of the Aggie Band. Ross's tenure also saw the college's first intercollegiate football game, played against the University of Texas.[10]

Program expansion

[edit]

| TAMU college/school/center founding[12] | |

|---|---|

| College/school/center | Year founded |

|

| |

| College of Agriculture and Life Sciences | 1911 |

| College of Architecture | 1905 |

| Bush School of Government and Public Service | 1997 |

| Mays Business School | 1961 |

| College of Education and Human Development | 1969 |

| College of Engineering | 1880 |

| College of Geosciences | 1949 |

| Health Science Center | 2013 |

| School of Law | 2013 |

| College of Liberal Arts | 1924 |

| College of Science | 1966 |

| College of Veterinary Medicine & Biomedical Sciences | 1916 |

By 1910, the school listed eight degree programs, including agriculture, architecture, agricultural engineering, chemical engineering, civil engineering, electrical engineering, mechanical engineering, and textile engineering. Five years later the state legislature, in cooperation with the United States Department of Agriculture, established the Texas Agricultural Extension Service, organized the Texas Forest Service, and authorized a School of Veterinary Medicine at the college.[3] The college was unprepared for the growth, and for the next ten years several hundred students lived in tents in a field in the middle of campus.[13]

During this time, women were also given a more official standing. The Texas Legislature in 1911 refused to give A&M permission to hold a summer semester unless women were also permitted to attend. For the next several decades during the summers cadets were not required to be in uniform and women could attend class and participate in intramural activities.[11]

Texas A&M graduates were called to use their military training during World War I, and by 1918, 49% of graduates of the college were in military service, a larger percentage than any other college or university.[3] In early September 1918, the entire senior class was mustered into military service, with plans to send the younger students at staggered dates throughout the next year. Many of the seniors were fighting in France when the war ended two months later.[13] In total, over 1,200 former students served as commissioned officers during World War I.[3]

Texas A&M Hillel, the oldest Hillel organization in the United States, was founded in 1920. The organization occurred three years before the national Hillel Foundation was organized at the University of Illinois.[14][15]

After the war, Texas A&M grew rapidly and became nationally recognized for its programs in agriculture, engineering, and military science. The first graduate school was organized in 1924,[3] and, in 1925, Mary Evelyn Crawford Locke became the first female to receive a diploma from Texas A&M, although she was not allowed to participate in the graduation ceremony.[16] The following month the board of directors officially prohibited all women from enrolling. In 1926, they codified that women in summer school had an unofficial status and could not pursue a degree. By 1930, however, over 1800 women had attended classes at A&M.[11]

In the late 1920s, following the discovery of oil on university lands, Texas A&M and the University of Texas negotiated a settlement for the division of the Permanent University Fund which enabled A&M to receive one-third of the revenue. This guaranteed wealth enabled A&M to expand. Enrollment increased even during the Great Depression, as student cooperative housing projects enabled the students to attend the school at low costs.[3] During the Depression, as professors were forced to accept a 25% pay cut, the board of directors partially rescinded its order against female enrollment, allowing no more than 20 females at a time to enroll in the school, and further restricting the group to daughters of professors.[11]

Texas A&M expanded its degree offerings in the late 1930s and awarded its first Ph.D. in 1940. Other programs at the college likewise began offering doctoral degrees throughout the next few decades.[3]

During World War II, Texas A&M produced 20,229 soldiers, sailors, and marines for the United States' war effort; of these, 14,123 were officers, more than the combined total of the United States Naval Academy and the United States Military Academy and more than three times the totals of any other Senior Military College.[3][17][18] Seven Aggies received the Medal of Honor during the worldwide conflict, tying with Virginia Tech as the most of any school outside of the military academies at West Point and Annapolis,[17] and 29 former students reached the rank of general. In addition, the college received nationwide exposure during the war when a reporter wrote a widely distributed story about the Aggie Muster on the island of Corregidor.[19] The intense interest resulted in a World War II propaganda movie, We've Never Been Licked, which was filmed on the A&M campus and showcased many of the school traditions.[20][21]

Though Texas A&M was originally established as a branch of the yet-to-be-created University of Texas, subsequent acts of the Texas Legislature never gave the university any authority over Texas A&M. This internal legal conflict in Texas was nullified in 1948 when Texas A&M became the flagship school of the newly created Texas A&M University System, a clear and separate institution from the University of Texas System. A&M's board of directors continued to oversee the system.[22] It is of note that the state constitution never was amended to confirm the separation between the university systems.

Enrollment soared as many former soldiers used the G.I. Bill to further their education. Unprepared for the growth, between 1949 and 1953 Texas A&M used the former Bryan Air Force Base as an extension of the campus. An estimated 5,500 men lived, studied, ate, showered, and attended classes at the base, which became known as the Annex (and later as Riverside Campus).[23]

In 1955, senior cadets at Texas A&M created the MSC Student Conference on National Affairs after attending SCUSA at the United States Military Academy at West Point to further the 'other education' of A&M and bring high caliber students and speakers from across Texas and the nation together to discuss issues of national importance. The keynote speaker at SCONA 1 in 1955 was United States Army Major General William J. Donovan, founder of the WWII-era Office of Strategic Services that later became the Central Intelligence Agency.[24]

Rudder era

[edit]

The Texas Legislature defeated a nonbinding resolution in the 1950s to encourage A&M to admit women. The school newspaper, The Battalion began writing editorials to encourage coeducation, causing the Student Senate to demand the editor of the paper resign. Later in the year students defeated 2–1 a campus resolution on coeducation.[11]

On March 26, 1959, retired Major General James Earl Rudder, who (outside of Sul Ross) arguably had the most significant effect on the campus (and especially in terms of transforming it into the modern university of today), became the 16th president of the college, his alma mater.[25][26] At the time, the college was still an all-male military school with a 7,500 student enrollment. Within several years of his arrival, the 58th Legislature of Texas officially changed the name of the school from the Agricultural & Mechanical College of Texas to Texas A&M University.[26] The Legislature specified that in the new name of the school, the A and the M were purely symbolic, reflecting the school's past, and no longer stood for "Agricultural and Mechanical".[3]

With Rudder's strong encouragement, in 1963, the A&M Board of Directors officially reversed their stance on admitting women.[26] The wives and daughters of faculty, staff and students as well as female staff members were finally allowed to officially participate in undergraduate programs, although they were not permitted to join the Corps of Cadets.[11]

The following year the college was officially integrated as A&M welcomed its first African-American student. More change ensued, as, in 1965, the board of directors voted to make membership in the Corps of Cadets voluntary. The same year the board voted to allow any woman, not just those connected to students and professors, to attend the university. The board required that Rudder approve each female applicant; he accepted any woman who met the academic requirements.[26] During Rudder's tenure, African-American students were also welcomed, and in 1967, James L. Courtney of Dallas became the first African American to receive an undergraduate degree from Texas A&M University. He remained at Texas A&M and, in 1970, became the first African American to receive a D.V.M. degree from the College of Veterinary Medicine.[27]

When Rudder died in 1970, after 11 years as president of the school, Texas A&M University had grown to more than 14,000 students from all 50 states and 75 nations.[26] The school had become coeducational and had even begun construction of an all-female dormitory.[11] The curriculum had been broadened, with upgraded academic and faculty standards, and the school had initiated a multimillion-dollar building program.[28]

Late 20th century (1970-1999)

[edit]Texas A&M's would continue its growth spurt after Rudder's death. On September 17, 1971, Texas A&M University was one of the first four institutions to be designated a sea-grant college in recognition of oceanographic development and research. A third designation was added on August 31, 1989, when Texas A&M was named a space-grant college. The university remains one of few institutions nationwide to hold designations as a land-, sea-, and space-grant college.[29]

In 1986, Texas A&M made plans to open a campus in Kōriyama, Japan, and accepted students starting in 1990 with the aim to transfer students to the College Station campus after two years of classes. The campus closed down in 1994 due to insufficient enrollment.[30]

Diversification

[edit]The Corps welcomed its first female members in the fall of 1974. At the time, the women were segregated into a special unit, known as W-1, and suffered harassment from many of their male counterparts.[31][32] Women were originally prohibited from serving in leadership positions or in the more elite Corps units such as the Fish Drill Team, the band, and Ross Volunteers. These groups were opened to female participation in 1985, following a federal court decision in a class-action lawsuit filed by a female cadet. Two years later, in 1990, female-only units were eliminated.[32]

In November 1976, the university denied official recognition to the Gay Student Services Organization on the grounds that homosexuality was illegal in Texas, and the group's stated goals—offering referral services and providing educational information to students—were actually the responsibility of university staff.[33] The students sued the university for violation of their First Amendment right to freedom of speech in February 1977. For six years, Gay Student Services v. Texas A&M University wound its way through the courts; although the trial court ruled in favor of Texas A&M several times, the 5th Circuit Court of Appeals repeatedly overturned the verdict.[33] The U.S. Supreme Court declined to review the case, letting stand the circuit court ruling that the students' free speech rights had been compromised.[34]

The case set a national precedent by removing legal restrictions on gay rights groups on campuses.[35] The subsequent recognition of the group provided a university precedent for allowing social organizations. In 1977, the university had also denied recognition to Sigma Phi Epsilon, a national social fraternity, because its presence on campus might result in "a social caste system".[33]

Presidential library

[edit]

The George Bush Presidential Library was established in 1997 on 90 acres (364,220 m2) of land donated by Texas A&M at the western edge of the campus. This tenth presidential library was built between 1995 and 1997 and contains the presidential and vice-presidential papers of George H. W. Bush and the vice-presidential papers of Dan Quayle.[36]

To coincide with the opening of the George Bush Presidential Library, Texas A&M established the George Bush School of Government and Public Service. The school, which offers a master's degree in Public Service and Administration (MPSA) and one in policy and international affairs (MPIA) as well as two research degrees, officially launched in 1997. It became a separate school within the university in 1999.[37]

Bonfire collapse

[edit]

At 2:42 a.m. on November 18, 1999, the partially completed Aggie Bonfire, standing 40 feet (12 m) tall and consisting of about 5000 logs, collapsed during construction. Of the 58 students and former students working on the stack, 12 were killed and 27 others were injured. The incident received nationwide attention, with over 50 satellite trucks broadcasting from the Texas A&M campus within hours.[38]

On November 25, 1999, the date that Bonfire would have burned, Aggies instead held a vigil and remembrance ceremony on site. Over 40,000 people, including former President George H.W. Bush and his wife Barbara and then-Texas governor George W. Bush and his wife Laura, lit candles and observed up to two hours of silence at the site of the Bonfire collapse.[39]

A commission put together by Texas A&M University discovered that a number of factors led to the Bonfire collapse, including "excessive internal stresses" on the logs and "inadequate containment strength", where the wiring used to tie the logs together was not strong enough. The wiring broke after logs from upper tiers were "wedged" into lower tiers.[38]

Texas A&M officials, Bonfire student leaders, and the university itself were the subject of several lawsuits by parents of the students injured or killed in the collapse.[40] On May 21, 2004, Federal Judge Samuel B. Kent dismissed all claims against the Texas A&M officials,[41] and, in 2005, 36 of the 64 original defendants, including all of the student leaders, settled their portion of the case for an estimated US$4.25 million, paid by their insurance companies.[42][43] A federal appeals court dismissed the remaining lawsuits against Texas A&M and its officials in 2007.[44]

21st century

[edit]

With strong support from Rice University and the University of Texas at Austin, the Association of American Universities inducted Texas A&M in May 2001, based on the depth of the university's research and academic programs.[45] Furthermore, in 2004, the honors organization Phi Beta Kappa opened its 265th chapter at Texas A&M.[46]

Following Hurricane Katrina in 2005, Texas A&M opened Reed Arena as a temporary shelter to house over 200 evacuees from New Orleans. Although school was barely in session and there was minimal notice, the students and staff of A&M prepared the facility, setting up several hundred beds on the arena floor and making arrangements for the evacuees to get new clothes and have medical checks. Aggie students organized a child care facility, and Aggie athletes escorted teenagers to the Aggie Rec Center to play basketball.[47] Less than three weeks later, Reed Arena was again opened as a temporary shelter for people fleeing Hurricane Rita.[48]

On December 18, 2006, former Texas A&M University president Robert M. Gates was sworn in as the 22nd U.S. Secretary of Defense. Gates's successor, Elsa Murano, on January 3, 2008, became both the university's first female and first Hispanic president.[49]

As of 2012, the university had an enrollment of more than 50,000, making the school the largest university in Texas.[50][51] By 2020, this number swelled even further to over 71,000 students enrolled making it the largest public university in the nation.[52]

Branch Campuses

[edit]Texas A&M has several branch campuses. Texas A&M University at Galveston was formed in 1962, in Galveston, Texas. This campus is home to the Texas A&M Maritime Academy and focuses on marine biology, marine sciences and oceanography. In 2003, the university opened an international branch in the West Asian country of Qatar.[53] Texas A&M University at Qatar had the distinction in 2011 of being the first school outside the U.S. recognizing engineers as members of Tau Beta Pi, the Engineering Honor Society.[54] The university opened a higher education center in 2018 in McAllen, Texas.[55]

In 2013, Texas A&M Health Science Center was formally merged into the university.[56] While the bulk of the health science center is located on main campus the health science center maintains campuses in Dallas, Houston, Round Rock and Temple. Of note is the Texas A&M University College of Dentistry. This campus, formerly the Baylor University School of Dentistry, was added to the health science center in 1996.

Also in 2013, the university purchased the Texas Wesleyan University School of Law and renamed it the Texas A&M School of Law. This campus is located in Fort Worth, Texas.

In 1962, Texas A&M was granted control of Bryan Air Force Base. This campus, formerly named Texas A&M Riverside Campus, was an extension of the main campus. This campus was transferred away from the Texas A&M proper to the Texas A&M University System in September 2015.[57]

Athletics

[edit]In 1914, Texas A&M became a charter member of the Southwest Conference until its dissolution in 1996. Texas A&M subsequently joined the Big Eight with The University of Texas at Austin, Baylor, and Texas Tech to form the Big 12 Conference. Texas A&M left the Big 12 Conference for the Southeastern Conference on July 1, 2012.[58] This ended Texas A&M's scheduled NCAA athletic competitions with its Texas Southwest Conference rivals.

As of the end of the 2012 athletics season, Texas A&M has won 19 national titles in all of its varsity sports. The school has two Heisman Trophy winners: John David Crow in 1957 and the 2012 winner, Johnny Manziel.[59]

References

[edit]- ^ a b "Morrill Act (1862)". National Archives. 2021-08-16. Retrieved 2024-02-11.

- ^ Green, Jennifer R.; Adams, John A. (2003-02-01). "Keepers of the Spirit: The Corps of Cadets at Texas A&M University, 1876-2001". Journal of Southern History. 69 (1): 3–33. doi:10.2307/30039895. ISSN 0022-4642.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n Dethloff, Henry C. "Texas A&M University". The Handbook of Texas. Retrieved 2014-10-02.

- ^ a b "The Texas Constitution, Article 7 – Education, Section 13 – Agricultural and Mechanical College". State of Texas. Archived from the original on June 10, 2007. Retrieved 2007-08-06.

- ^ Chapman, David L. "Thomas S. Gathright: Dedicated to Success, Doomed to Failure". Cushing Memorial Library and Archives. Archived from the original on September 19, 2006. Retrieved 2008-02-27.

- ^ Lane, John Jay (1903). History of Education in Texas (PDF). Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office. p. 271 – via Texas Legal Guide.

- ^ Dethloff, Henry C. (1975). A Pictorial History of Texas A&M University, 1876–1976. College Station, Texas, Texas: Texas A&M University Press. pp. 16–17.

- ^ Dethloff (1975), p. 18.

- ^ Dethloff (1975), pp. 21–22.

- ^ a b c d Ferrell, Christopher (2001). "Ross Elevated College from 'Reform School'". The Bryan-College Station Eagle. Archived from the original on 2007-10-16. Retrieved 2008-06-24.

- ^ a b c d e f g Kavanagh, Colleen (2001). "Questioning Tradition". The Bryan-College Station Eagle. Archived from the original on 2013-01-04. Retrieved 2008-06-24.

- ^ "Academic Departments – Texas A&M University, College Station, TX". Tamu.edu. Archived from the original on October 10, 2014. Retrieved September 14, 2014.

- ^ a b Liffick, Brandie (October 30, 2001). "Tradition spanning generations". The Battalion. Archived from the original on 2007-09-29. Retrieved 2007-03-22.

- ^ From Christian Science to Jewish Science: Spiritual Healing and American Jews Oxford University Press p. 160

- ^ Gabrielle Birkner (2005-05-06). "A Cushy Fit In Bush Country". The Jewish Week. Archived from the original on May 16, 2005. Retrieved 2007-12-30.

- ^ "Crawford Learning Community". Texas A&M University Department of General Academic Programs. Archived from the original on 2009-07-27. Retrieved 2008-06-24.

- ^ a b Keepers of the Spirit, p. 160, by John A. Adams Jr.

- ^ "Texas A&M Standard". Texas A&M Corps of Cadets. Archived from the original on 2007-02-03. Retrieved 2007-02-27.

- ^ "Aggie Muster". Emerald Coast A&M Club. Archived from the original on 2007-09-27. Retrieved 2006-12-17.

- ^ Crowther, Bosley (August 19, 1943). "Movie Review: We've Never Been Licked (1943)". The New York Times. Retrieved 2007-08-03.

- ^ "We've Never Been Licked". AnneGwynne.Com. Archived from the original on 2005-12-26. Retrieved 2007-08-03.

- ^ "A&M System History". Texas A&M University System. Archived from the original on February 9, 2007. Retrieved 2007-03-22.

- ^ Gillentine, Kristy (March 11, 2007). "Aggies recall days at Annex". The Bryan-College Station Eagle. Archived from the original on September 30, 2007. Retrieved 2008-06-24.

- ^ Bacon, Amy L. (2009). Building leaders, living traditions : the Memorial Student Center at Texas A&M University (1st ed.). College Station: Texas A&M University Press. ISBN 978-1-60344-328-9. OCLC 680622541.

- ^ Dethloff (1975), p. 184

- ^ a b c d e Ferrell, Christopher (2001). "Rudder's influence is evident on campus". The Bryan-College Station Eagle. Archived from the original on 2007-10-16. Retrieved 2008-06-24.

- ^ Charleton, Gene (1998-01-19). "First African-American Vet Grad Honored As Outstanding Alumnus". Texas A&M University Office of University Relations. Archived from the original on 2009-07-27. Retrieved 2008-06-24.

- ^ Dethloff (1975), p. 188.

- ^ "About Us". Texas Sea Grant College Program. Archived from the original on August 21, 2007. Retrieved 2007-05-10.

- ^ Pollack, Andrew (26 September 1994). ""Koriyama Journal; American Colleges Are Flunking Badly in Japan"". New York Times. Retrieved November 3, 2022.

- ^ Korzenewski, Claire-Jean (September 9, 2004). "The First Women to Join the Cadets". The Bryan-College Station Eagle. Archived from the original on July 4, 2011. Retrieved 2007-03-22.

- ^ a b Nauman, Brett (September 10, 2004). "Women Joined Corps 30 Years Ago". The Bryan-College Station Eagle. Archived from the original on September 27, 2007. Retrieved 2007-03-22.

- ^ a b c Pinello, Daniel R. (2003). Gay rights and American law. University of Cambridge. pp. 58–59. OCLC 051012147.

- ^ Greenhouse, Linda (April 2, 1985). "Supreme Court Roundup; Case of Ministry Student is Accepted". New York Times. Retrieved October 28, 2009.

- ^ Wiessler, Judy (April 2, 1985). "Texas A&M loses legal fight against gay student group". Houston Chronicle. p. Section 1, page 1. Retrieved October 28, 2009.

- ^ "The Birth of the Tenth Presidential Library: The Bush Presidential Materials Project, 1993–1994". George Bush Presidential Library. Archived from the original on 2007-08-07. Retrieved 2007-03-22.

- ^ "The Bush School of Government and Public Service: History". Texas A&M University. 2005. Archived from the original on 2007-06-24. Retrieved 2007-03-22.

- ^ a b Cook, John Lee Jr. "Bonfire Collapse" (PDF). U.S. Department of Homeland Security. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2007-02-07. Retrieved 2007-03-03.

- ^ Whitmarsch, Geneva (November 26, 1999). "Thousands Mourn Fallen Aggies". The Bryan-College Station Eagle. Archived from the original on September 30, 2007. Retrieved 2008-06-24.

- ^ LeBas, John (June 23, 2002). "Suits claim A&M tried to skirt Bonfire liability". The Bryan-College Station Eagle. Archived from the original on September 27, 2007. Retrieved 2008-06-24.

- ^ Pierce, Carrie (June 2, 2004). "Court says A&M is not liable in Bonfire lawsuit". The Battalion. Archived from the original on 2007-09-29. Retrieved 2007-03-13.

- ^ Kapitan, Craig (September 3, 2006). "Bonfire case under scrutiny by court". The Bryan-College Station Eagle. Archived from the original on September 30, 2007. Retrieved 2007-03-13.

- ^ Avison, April (July 27, 2006). "Judge dismisses a Bonfire lawsuit". The Bryan-College Station Eagle. Archived from the original on September 27, 2007. Retrieved 2007-03-13.

- ^ Van Der Werf, Martin (April 25, 2007). "Appeals Court Upholds Dismissal of Lawsuits Over Texas A&M Bonfire Accident". The Chronicle of Higher Education. Retrieved 2007-05-24.

- ^ "Texas A&M Selected For Membership In Association Of American Universities" (Press release). Texas A&M University. May 7, 2001. Archived from the original on July 27, 2009. Retrieved 2008-06-24.

- ^ "Texas A&M Joins Phi Beta Kappa Ranks" (Press release). Texas A&M University. February 17, 2004. Archived from the original on July 27, 2009. Retrieved 2008-06-24.

- ^ Gates, Robert M. (September 6, 2005). "Relief Efforts at Texas A&M". Texas A&M University. Archived from the original on 2007-02-14. Retrieved 2007-02-27.

- ^ Watkins, Matthew (September 22, 2005). "A&M to host coastal evacuees, hospital transfers". The Battalion. Archived from the original on September 29, 2007. Retrieved 2007-02-27.

- ^ Tresaugue, Matthew (2008-01-04). "Murano wins confirmation as president of Texas A&M". Houston Chronicle. Retrieved 2008-06-24.

- ^ "Enrollment Surpasses 50,000 For First Time In History". TAMU Times. Texas A&M University. Archived from the original on April 2, 2012. Retrieved September 10, 2011.

- ^ "Texas Higher Education Enrollments". Texas Higher Education Coordinating Board.

- ^ Rodriguez, Megan (19 September 2020). "Texas A&M University enrollment grows despite pandemic". The Eagle. Retrieved 2 December 2020.

- ^ "About Texas A&M". Texas A&M University. College Station, TX.

- ^ "Tau Beta Pi Chapter Recognized Internationally". Archived from the original on 6 September 2014. Retrieved 6 September 2014.

- ^ "About Us: McAllen HEC". Texas A&M University. Retrieved 6 December 2020.

- ^ "Texas A&M Health Science Center Moves Under Administration of Texas A&M University" (Press release). Texas A&M University. 12 July 2013. Archived from the original on 21 July 2013. Retrieved 16 July 2013.

- ^ "Texas A&M announces plans to expand Riverside campus". The Eagle. Retrieved 6 December 2020.

- ^ Russo, Ralph (September 5, 2011). "SEC: Texas A&M to join in July 2012". The Washington Times. Associated Press. Retrieved September 28, 2011.

- ^ "Texas A&M Football: Heisman Trophy Winners". Texas A&M Athletics - Home of the 12th Man. Retrieved 2 December 2020.

External links

[edit]