History of Santa Monica, California

This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these messages)

|

| History of California |

|---|

|

| Periods |

| Topics |

| Cities |

| Regions |

| Bibliographies |

|

|

The history of Santa Monica, California covers the significant events and movements in Santa Monica's past.

Population by decade

[edit]- 1880 – 417

- 1890 – 1,580

- 1900 – 3,057

- 1910 – 7,847

- 1920 – 15,252

- 1930 – 37,146

- 1940 – 53,500

- 1950 – 71,595

- 1960 – 83,249

- 1970 – 88,289

- 1980 – 88,314

- 1990 – 86,905

- 2000 – 84,084

- 2010 – 89,736

Pre-history

[edit]Santa Monica was long inhabited by the Tongva people. The village of Comicranga was established in the Santa Monica area.[1] One of the village's notable residents was Victoria Reid, who was the daughter of the chief of the village.[2] During the Spanish period, she was taken to Mission San Gabriel from her parents at the age of six.[1] The general area of Santa Monica was referred to as Kecheek.[3]

1760s

[edit]The first non-indigenous group to set foot in the area was the party of explorer Gaspar de Portolà, who camped near the present day intersection of Barrington and Ohio Avenues on August 3, 1769. There are two different versions of the naming of the city. One says that it was named in honor of the feast day of Saint Monica (mother of Saint Augustine), but her feast day is actually May 4. Another version says that it was named by Juan Crespí on account of a pair of springs, the Kuruvungna Springs, that were reminiscent of the tears that Saint Monica shed over her son's early impiety.[4] The Kuruvungna Springs ("the place where we are in the sun") are sacred to the Tongva People.[5]

Regarding the latter, Crespi did note in his diary that the group found a Tongva village at the springs (where the SE corner of the campus of University High School is today). As is also recorded in his diary, Crespí named the place San Gregorio,[4] while the expedition soldiers called it "El Berendo" after a deer they wounded there.[6] The springs were probably commonly called by the name Santa Monica by the turn of the 19th century. By the 1820s, the name Santa Monica was in use and the name's first official mention occurred in 1827 in the form of a grazing permit,[4] quickly followed by the grant filing for the Rancho Boca de Santa Monica in 1828.[6]

1870s

[edit]Government sovereignty in California passed from Mexico to the US on February 2, 1848. The northern sections of the city of Santa Monica once belonged to Rancho San Vicente y Santa Monica and Rancho Boca de Santa Monica. The Sepulveda family sold 38,409 acres (155 km2) of Rancho San Vicente y Santa Monica for $54,000 in 1872 to Colonel Robert S. Baker and his wife, Arcadia Bandini de Stearns Baker. Bandini was the daughter of Juan Bandini, a prominent and wealthy early Californian, and was the widow of Abel Stearns, once the richest man in Los Angeles. Baker also bought a half interest in Rancho Boca de Santa Monica. Nevada Senator John P. Jones bought a half interest in Baker's property in 1874.

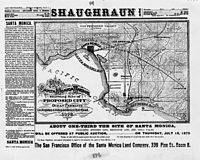

Jones and Baker subdivided part of their joint holdings in 1875 and created the town of Santa Monica. The town site fronted on the ocean and was bounded on the northwest by Montana Avenue, on the southeast by Colorado Avenue and on the northeast by 26th Street. The avenues were all named after the states of the West, the streets being simply numbered. The first lots in Santa Monica were sold on July 15, 1875.

Jones built the Los Angeles and Independence Railroad, which connected Santa Monica and Los Angeles, and a wharf out into the bay. The first town hall was a modest 1873 brick building, later a beer hall, and now part of the Santa Monica Hostel. It is Santa Monica's oldest extant structure.

The southwestern section of the city originally belonged to the Rancho La Ballona of the Machado and Talamantes families. Mrs. Nancy A. Lucas purchased 861 acres (3.48 km2) from the rancho in 1874 for $11,000. The property was farmed by her sons, and a parcel of 100 acres (0.40 km2) was sold to Williamson Dunn Vawter for subdivision in 1884.

- Santa Monica in the 1870s

-

Advertisement for first land sale in Santa Monica, 1875.

-

Investors gather to buy lots in the new "City on the Sea", 1875.

-

Sketch of Santa Monica, 1875.

-

Santa Monica, 1877

-

An early Santa Monica Pier, 1877

1880s

[edit]The town's new business district was initially centered around the current Third Street Promenade. Early street names consisted of both numbers and the names of western states; however Utah eventually became Broadway and Oregon became Santa Monica Boulevard.

By 1885, the town's first hotel, the Santa Monica Hotel, was constructed on Ocean Ave., between Colorado and Utah in 1885. The Hotel burned in 1887. The 125-room "Arcadia Hotel" opened on January 25, 1887. Named for Arcadia Bandini, it was one of the great hotels on the Pacific Coast of its era. The hotel was the site where Colonel Griffith J. Griffith shot his wife in 1903, which led to their divorce and his (short) imprisonment.

The residents voted to incorporate November 30, 1886, and chose the first board of trustees. The original townsite was bounded by Montana Avenue on the north, 26th Street on the east, Colorado Avenue on the south, & the Pacific Ocean on the west.

Senator Jones built a mansion, Miramar, and his wife Georgina planted a Moreton Bay Fig tree in its front yard in 1889. (The tree is now in the courtyard of the Fairmont Miramar Hotel and is the second-largest such tree in California, the largest being the tree in Santa Barbara.)

- Santa Monica in the 1880s

-

A busy day on the beach, 1880.

-

Businesses on Third Street, between Utah and Oregon.

-

Santa Monica Hotel, 1885.

-

Santa Monica, 1887.

-

The Arcadia Hotel, oceanside.

-

The Arcadia Hotel, street-side.

-

Looking south across the bluffs, the Arcadia Hotel sits at the end of the pier, 1888.

-

Senator Jones' Miramar mansion

1890s

[edit]When the Southern Pacific Railroad arrived at Los Angeles, a dispute erupted over where to locate the seaport. The SP preferred Santa Monica, while others advocated for San Pedro Bay. The Long Wharf was built in 1893 at the north end of Santa Monica to accommodate large ships and was dubbed Port Los Angeles. At the time it was constructed, it was the longest pier in the world at 4700 feet, and accommodated a train. The plan did not last: San Pedro Bay, now known as the Port of Los Angeles, was selected by the United States Congress in 1897. Still, the Long Wharf acted as the major port of call for Los Angeles until 1903. Though the final decision disappointed Jones and other property owners, the selection allowed Santa Monica to maintain its scenic charm. The rail line down to Santa Monica Canyon was sold to the Pacific Electric Railway, and was in use from 1891 to 1933.

Meanwhile, Abbot Kinney acquired deed to the coastal strip previously purchased by W.D. Vawter and named the area Ocean Park in 1895. It became his first amusement park and residential project. A race track and golf course were built on the Ocean Park Casino. After a falling out with his partners he focused on the south end of the property, which he made into Venice of America.

- Santa Monica in the 1890s

-

[[Long Wharf with train, 1893

-

Bustling Santa Monica beach, 1890

-

View north from Hotel ArcadiaArcadia Hotel, 1893 (note the 3 piers)

1900s

[edit]Amusement piers became enormously popular in the first decades of the 20th century. The extensive Pacific Electric Railroad easily transported to the beaches people from across the Greater Los Angeles Area. Competing pier owners commissioned ever larger roller coaster rides. Wooden piers turned out to be readily flammable, but even destroyed piers were soon replaced. There were five piers in Santa Monica alone, with several more down the coast. The earliest part of the current Santa Monica Pier, which is now the last remaining amusement pier, was built in 1909 on what was referred to as the North Bay. The second half, an amusement park pier, was built later and the two rival piers were merged.

Among the South Bay piers, the most notable in this period was Abbot Kinney's Venice of America pier, started in 1904 and built to rival his former partner's Ocean Park Pier. Located at the end of Windward Avenue in Venice, Kinney's pier was 900 feet long, 30 feet wide and included an Auditorium, large replica Ship Cafe, Dance Hall, Dentzel carousel, a Japanese Tea House and an Ocean Inn Restaurant.[7] Venice soon became considered its own neighborhood.

A new charter was adopted in 1906 that converted the city government to a Mayor – Council form of government. Under the new charter, the City Council was composed of one Mayor with veto power, and one Councilmember from each of its seven wards.

Around the start of the 20th century, a growing population of Asian Americans lived in or near Santa Monica and Venice. A Japanese fishing village was located near the Long Wharf while small numbers of Chinese lived or worked in both Santa Monica and Venice. The two ethnic minorities were often viewed differently by White Americans who were often well-disposed towards the Japanese but condescending towards the Chinese. The Japanese village fishermen were an integral economic part of the Santa Monica Bay community.[8]

- Santa Monica in the 1900s

-

Ocean Park coast, 1900

-

Kinney's Venice pier, 1905

-

Japanese fishing village at the end of the Long Wharf, 1900.

-

Santa Monica, 1905

1910s

[edit]Fraser's Million Dollar Pier claimed to be the largest in the world at 1250 feet long and 300 feet wide. The pier housed a spacious dance hall, two carousels, an exhibit of premature babies in incubators at Frederick House,[9] the Crooked House fun house, the Grand Electric Railroad, the Starland Vaudeville Theater, Breaker's Restaurant, and a Panama Canal model exhibit. It burned 15 months after it opened.[7]

A new charter was adopted in 1914 that converted the city government to a commission form. This proved to be very weak, especially since the police commissioner was poorly paid and had no accountability.

Auto racing became popular. Drivers would race an 8.4-mile loop made up of city streets. The Free-For-All Race was conducted between 1910 and 1912. The United States Grand Prix was held in Santa Monica in 1914 and 1916, awarding the American Grand Prize and the Vanderbilt Cup trophies. By 1919, the events were attracting 100,000 people, at which point the city halted them.

- Santa Monica in the 1910s

-

Ocean Park Pier burns, 1912

-

Santa Monica City Hall, 1910

-

Steps down the Palisades, 1915

1920s

[edit]Donald Wills Douglas, Sr. founded the Douglas Aircraft Company in 1921 with his first plant on Wilshire Boulevard. He built a plant in 1922 at Clover Field (Santa Monica Airport), which was in use for 46 years. In 1924, four Douglas-built planes took off from Clover Field to attempt the first aerial circumnavigation of the world. Two planes made it back, after having covered 27,553 miles in 175 days, and were greeted on their return September 23, 1924, by a crowd of 200,000 (generously estimated). The Douglas Company (later McDonnell Douglas) kept facilities in the city until 1975. The entire facility was demolished and removed by 1977.

In 1922, a local newspaper, discussing African Americans, stated "We don't want you here; now and forever, this is to be a white man's town".[10]

The nationwide prosperity of the 1920s was felt in Santa Monica. The population increased from 15,000 to 32,000 at the end of the decade. Downtown saw a construction boom with many important buildings going up such as Henshey's Department Store (destroyed) and the Criterion Theater. Elegant resorts were opened, including the 1925 Miramar Hotel and the 1926 Club Casa del Mar. The Los Angeles firm of Walker & Eisen designed the art deco Bay City Building, a 13-story skyscraper topped with a huge four-faced clock that was finished in 1930.

Beach volleyball is believed to have been developed in Santa Monica during this time. Duke Kahanamoku brought a form of the game with him from Hawaii when he took a job as athletic director at the Beach Club. Competition began in 1924 with six-person teams, and by 1930 the first game with two-person teams took place.

La Monica Ballroom opened in 1924 on the Santa Monica Pier. It was capable of holding 10,000 dancers in its over 15,000 square foot (1,400 m2) area. A major storm in 1926 almost destroyed the pier and the ballroom, necessitating major repairs. La Monica hosted many national radio and television broadcasts in the early days of networks, before it was finally torn down in 1962. From 1958 to 1962 the ballroom became one of the largest roller-skating rinks in the western U.S.

Comedian Will Rogers bought a substantial ranch in Santa Monica Canyon in 1922. Among his improvements was a polo field where he played with friends Spencer Tracy, Walt Disney and Robert Montgomery. Upon his untimely death it was discovered that he had generously deeded to the public the ranch now known as Will Rogers State Historic Park, Will Rogers State Park, and Will Rogers State Beach. More recent residents of Santa Monica Canyon have included Christopher Isherwood, Don Bachardy, Jane Fonda, and Tom Hayden (the last two who previously lived in Ocean Park). The southern rim of the canyon is the oldest residential part of Santa Monica, while most of the canyon is in the City of Los Angeles.

In 1928, Will Rogers sold a parcel with two large houses on the beach at the base of the bluffs to William Randolph Hearst, who then gave it to Marion Davies. Architect Julia Morgan oversaw the construction of what ultimately became the $7 million, 5-building, 118-room Ocean House. As with other lavish Hearst/Morgan projects it contained entire rooms removed from antique European buildings. Davies was a vivacious and popular hostess and Ocean House saw many grand parties of Hollywood celebrities. Davies sold the property in 1945 for just $600,000 to a failed attempt at a hotel. Most of the property was torn down in 1958, leaving only the North House with a marble pool and tennis courts. The remaining property was sold to the State of California and leased as the private Sand and Sea Club. Following the expiration of the 30-year lease in 1990, management of the property was turned over to the City of Santa Monica. For a short period of time until the 1994 Northridge earthquake, the City operated the site as a public beach facility. It was also used as a shooting location, most notably in the TV show Beverly Hills, 90210, in which it was the Beverly Hills Beach Club. Redevelopment of the property has been a political issue in the city since the 1990s. In 2006, the City Council approved plans for the first ever public beach club, which included the rehabilitation of the property and construction of new facilities. The project, now under construction, is made possible by a generous gift from the Annenberg Foundation, at the recommendation of Wallis Annenberg, and in partnership with the City of Santa Monica and California State Parks. The Annenberg Community Beach House at Santa Monica State Beach opened to the public on April 25, 2009. The total construction costs were roughly $30 million. Local residents succeeded in forcing the city to significantly limit its hours of operation.

The area around the Davies mansion became known as the Gold Coast. Stretching along Pacific Coast Highway between Santa Monica Canyon and the Santa Monica Pier it became fashionable in the 1930s for beach homes of discrete celebrities. Following the lead of Rogers and Davies, other actors with homes there have included Norma Talmadge, Greta Garbo and Cary Grant. Douglas Fairbanks spent his last years living there. Peter Lawford had a house there in the 1960s.

Ed Kolpin, Jr., opened a small tobacco, pipe, and cigar store in Santa Monica, the Tinder Box, in 1928. Later it moved to its current location in 1948 where it began serving the many Hollywood celebrities living nearby. Part of the attraction were the famous pipes handmade by Kolpin himself. In 1959 Kolpin began a tobacco-store franchise, at first locally and then by the mid-1960s there were Tinder Box stores in malls across America. The franchise business was sold in the 1970s, but Kolpin still owns and operates the original store as of 2003.

1930s

[edit]

The Great Depression hit Santa Monica deeply. One report gives citywide employment in 1933 of just 1,000. Hotels and office building owners went bankrupt. The pleasure piers were a cheap form of entertainment that got cheaper, attracting a coarser crowd. Muscle Beach, located just south of the Santa Monica Pier, started to attract gymnasts and body builders who put on free shows for the public, and continues till today.

In the 1930s, corruption infected Santa Monica (along with neighboring Los Angeles). This aspect of the city is depicted in various Raymond Chandler novels, where Santa Monica is thinly disguised as Bay City. A sequence in Chandler's Farewell, My Lovely was inspired by the true story of the S.S. Rex.[11] Beginning in 1928, gambling ships started anchoring in Santa Monica Bay just beyond the 3-mile (5.6 km) limit. Water taxis ferried patrons from Santa Monica and Venice. The largest such ship was the S.S. Rex, launched in 1938 and capable of holding up to 3,000 gamblers at a time. The Rex was a red flag to anti-gambling interests. After state Attorney General Earl Warren got a court order to shut the ships down as a nuisance, the crew of the Rex initially fought off police by using water cannons and brandishing sub-machine guns. The engine-less ship surrendered after nine days in what newspapers called The Battle of Santa Monica Bay. Its owner, Anthony Cornero, went on to build the Stardust casino in Las Vegas, Nevada.

The greatest benefit to the city came from the Douglas Corporation when it built the DC-3 commercial aircraft. The DC-3, which first flew from Clover Field, was a terrifically successful airliner that transformed the air transportation business and brought needed jobs to the city. In a more modest show of entrepreneurship, Merle Norman founded Merle Norman Cosmetics in 1931 by making creams and cosmetics on her kitchen stove. Both her former house and her 1933 Streamline-styled business headquarters are well maintained.

The federal Works Project Administration helped build several buildings in the city, most notably City Hall. The 1938 Art Deco structure was designed by Donald Parkinson and features terrazzo mosaics by Stanton Macdonald-Wright. The main Post Office and Barnum Hall (Santa Monica High School auditorium) were among several other WPA projects.

1940s

[edit]

Douglas's business grew astronomically with the onset of World War II, employing as many as 44,000 people in 1943. To defend against air attack set designers from the Warner Brothers Studios prepared elaborate camouflage that disguised the factory and airfield.[12][13]

In 1945, Santa Monica City College started the Community Radio Workshop (CRW) to teach returning GIs broadcasting and used the call letters KCRW. (Later KCRW became a popular and innovative NPR affiliate.)

The Sears building was built in 1947 at the south end of the retail district and has retained architect Rowland Crawford's original late-Moderne styling.

The RAND Corporation began as a project of the Douglas Company in 1945, and spun off into an independent think tank on May 14, 1948. RAND eventually acquired a 15-acre (61,000 m2) campus centrally located between the Civic Center and the pier entrance.

As a response to the corruption and inefficiency that grew in the 1930s, the current charter was enacted in 1946. The city government adopted a council-manager government.

1950s

[edit]

Papermate opened its Santa Monica factory in 1957. The plant produced 600 million ballpoint pens in 1971 and closed in 2005.

The 3,000-seat Santa Monica Civic Auditorium was built on the site of Santa Monica's red-lined African American neighborhood, known as Belmar. Construction began soon after the removal of Belmar's residents. The auditorium was designed in the International Style by Welton Becket, opened in 1958.[14] From 1961 to 1968 the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences held its annual Oscar awards ceremony there. Performers that have appeared over the decades include: Joan Baez, The Beach Boys, Tony Bennett, David Bowie, Dave Brubeck, Buzzcocks, The Carpenters, Ray Charles, The Clash, Bill Cosby, Bob Dylan, Ella Fitzgerald, Allen Ginsberg, Arlo Guthrie, Jimi Hendrix, Bob Hope, Elton John, Led Zeppelin, André Previn, Public Enemy, Ramones, The Rolling Stones, Pete Seeger, Bruce Springsteen and the E Street Band, T.Rex, Jonathan Winters, and countless others. Since the late 1980s the auditorium has been more popular for trade conventions than performances. The films The T.A.M.I. Show and Urgh! A Music War were shot there.

Pacific Ocean Park, the last of the great amusement piers, opened in 1958. While it temporarily eclipsed competitor Disneyland, attendance later plummeted and by 1967 the park was foreclosed for back taxes. It sat empty and rotting, an unattractive "attractive nuisance" until finally removed in 1974.

Adjacent to Pacific Ocean Park was the rock and roll club, The Cheetah, which featured early performances by such acts as The Doors, Alice Cooper, Pink Floyd, Love, The Mothers of Invention, The Seeds, Buffalo Springfield and others. It closed in 1968.

The Synanon drug rehabilitation cult moved into the old National Guard building in 1959 and added their strange presence to the area. In 1967 it moved into the swank Del Mar Club until 1978. After that they held a small presence until shut down in 1991.[15][16]

1960s

[edit]

The completion of the Santa Monica Freeway in 1966 brought the promise of new prosperity for some, although it was at the cost of decimating Santa Monica's red-lined African American enclave and Hispanic "La Viente" barrio running between Olympic and Pico.

Third Street in downtown was converted into the Santa Monica Mall in 1965, an innovative but ultimately unsuccessful development that turned the three block core of the retail district into an open-air pedestrian mall. Large parking structures were built, but rarely filled. Within a couple of decades it was in severe decline. (The Santa Monica Mall, just prior to its conversion to the Third Street Promenade, is a location for some scenes in the movie, Pee-wee's Big Adventure).

The Douglas plant closed in 1968, depriving Santa Monica of its largest employer. A decade passed before the site was redeveloped into an office park. The Museum of Flying was opened on the same site another decades later, in 1989.

Bandleader Lawrence Welk built the Champagne Towers apartment building and the adjoining 300-foot-tall (91 m) Lawrence Welk Plaza in 1969. The plaza is now known by its address, 100 Wilshire, and it is still the tallest building in the city.

1970s

[edit]During the 1970s, a remarkable number of notable fitness- and health-related businesses started in the city. The Supergo bicycle shop (originally named Bikecology founded by Susan and Alan Goldsmith as a pro ten-speed bike shop opened in 1971, and was ranked the top grossing bike shop in America by the time it relocated from Wilshire Blvd to the corner of 5th and Broadway in 1995. And coincidentally work on the bicycle path along the beach was undertaken by the city. The Santa Monica Track Club, founded in 1972 by Joe Douglas, has helped the careers of many Olympians, such as Carl Lewis. Sensei James Field opened his dojo in 1974, which became one of the primary Shotokan karate schools in the US and is now called the Japan Karate Association (JKA) Santa Monica. Joe Gold, who had sold his chain of Gold's Gyms years before, started the World Gym chain in 1977. Nathan Pritikin opened the Pritikin Longevity Center in the Casa Del Mar building in 1978 after prior owner Synanon tried to murder attorney Paul Morantz by placing rattlesnake in his mailbox.[16] Ocean Park resident Jane Fonda opened a small aerobics studio on Main Street.

In the late 1970s, progressivism became the dominant political force in Santa Monica. Santa Monicans for Renters' Rights (SMRR) formed in 1978 and was led by Ruth Yannatta Goldway, Derek Shearer, Dennis Zane, and Reverend James Conn with support from Tom Hayden and Jane Fonda. Conn's Ocean Park Community Organization (OPCO) was formed in 1979 as an adjunct to the Church in Ocean Park, partly in reaction to the rapid pace of change along Main Street. It was the first of what became nine community organizations that serve as neighborhood advocates. A strict rent control ordinance passed in 1979 and SMRR achieved a council majority in 1981. It has largely remained the controlling political organization since then.

By 1977, the large 1894 "American Foursquare"-style home of Roy Jones (son of founder John P. Jones) was threatened with destruction. It had been converted into rooming houses and was decrepit. It, along with an adjoining 19th century house, was saved by being relocated to Main Street in Ocean Park and renovated. The Jones house became the home of the Santa Monica Heritage Museum and the other house became a restaurant. The salvation of the buildings was representative of the changes taking place in the city.

The late-1970s/early-1980s situation comedy Three's Company was set in Santa Monica.

1980s

[edit]After the economic doldrums of the 1960s and early 1970s, the city's economy began to recover in the 1980s. An early sign of that change was in the neighborhood of Ocean Park. Main Street, a quaint mile of sawdust bars and dilapidated stores selling old furniture, was upgraded by the concerted efforts of a new generation of owners. Soon it was attracting increasingly expensive boutiques and restaurants. At the northern end of Main Street adjacent to the still-declining Santa Monica Mall, a city block was levelled in 1980 to build a new mall, Santa Monica Place, designed by architect Frank Gehry. Further south on Main Street, the mixed-use museum, retail, and restaurant complex, Edgemar – also designed by Frank Gehry – opened in 1988.

While the Santa Monica Pier had been preserved from intentional destruction in 1973, it was nonetheless poorly maintained. By the 1980s it had become a blight. The area around the pier was filled with poorly built and maintained buildings that housed seedy biker bars and head shops. The pier itself had dilapidated bars, an odd plaster statue store, and creepy game arcades. The city put off repairing the breakwater that protected the pier and the so-called "yacht harbor" immediately north. Studies were made for rehabilitation of the pier and repair of the breakwater, but they were never acted upon. In 1983 major winter storms, part of the El Niño weather pattern, struck Santa Monica on January 27 and again on March 1. The storms destroyed more than a third of the pier, along with stores, bars, cars, and a large crane brought in to begin repairs. Rebuilding the pier was a contentious effort, costing $43 million. Ultimately the work was completed and the pier remains the city's best-known landmark. Three interesting buildings owned by the city were abandoned and destroyed, including the Sinbad's Restaurant that featured a large whale's tail in the facade.

In the 1980s, the city put together the plan for turning the failed Santa Monica Mall into the Santa Monica Promenade. The project, completed in 1989 has proven to be a huge success and is a major regional shopping and entertainment center. Between 1988 and 1998, taxable sales in the city grew 440%, quadrupling city revenues. Retails rents in the development area also quadrupled. More than $500 million of private money has been invested into the Promenade and the adjacent streets in the Bayside District Corporation business association.

The city opened its Public Electronic Network (PEN) in 1989, providing citizens with a bulletin board system (BBS) to discuss local issues and access city services. PEN was the first municipally operated BBS in the world. While plagued by the ills common to BBSes, the site empowered residents. Due in part to the placement of publicly available terminals in libraries, homeless persons and their issues received considerable attention on PEN. The SWASHLOCK (Showers, WASHers, and LOCKers) plan was developed on PEN and implemented in 1993. PEN also served as a center to organize opposition to the 1990 proposal to redevelop 415 PCH.

1990s

[edit]The 1990s saw continued development in Santa Monica. The Promenade caught on. Colorado Place, Water Garden, and other nearby office developments on the east side of town attracted MGM, Sony, Symantec, and other corporations. The Shutters Hotel was the first of several new hotels built between the pier and Pico Boulevard. One of them, the Loews, is on the site of the long forgotten Arcadia Hotel. The Casa Del Mar returned to its former glory as a luxury hotel in 1999 after a reported $60 million renovation by the owners of the Shutters Hotel. Even the comparatively dowdy Miramar Hotel found new prominence with the many visits of President Bill Clinton.

In 1994, an old rail station was transformed by the city into Bergamot Station, a collection of art galleries that has become a center of art exhibition and retailing.

The 1994 Northridge earthquake caused the loss of many residences and historic buildings, particularly on the north side of the city. Other notable damage: St. John's hospital came close to collapsing; Honda of Santa Monica's parking structure pancaked crushing numerous cars. In all, 100 buildings were condemned outright, including 3,100 apartment units, while far more suffered repairable damage.

The Evening Outlook, which had been purchased by the Copley Press newspaper chain in 1983, was closed in 1998 after 123 years of reporting.[17][18] It reportedly had 20,000 paid subscription at the time of the closure.[19]

MTBE, a major gasoline additive (10% by volume), was discovered in the city's water wells in August 1995. The MTBE was found almost by accident since it was not on the list of known contaminants and acceptable level had not been set. The city waters engineers had to research the hazard and they raised the alarm. Within a year all five wells were closed, leading to the loss of 45% of the city's water supply. One well had a concentration of 600 parts per billion, while another rose from 14 parts per billion to 490 parts per billion within a year. The California EPA guidelines now call for no more than 35 parts per billion. The city's well field is in the Charnock Sub-Basin, a small aquifer in Mar Vista, Los Angeles that both Santa Monica and Culver City draw upon. To maintain supply to customers Santa Monica was forced to purchase water from the Metropolitan Water District of Southern California (MWD) at a cost of over $1.1 million per year. Cleanup of the site is ongoing at a current cost of $3 million per year, paid for by the responsible parties, principally: Shell, Chevron and Exxon. Following this discovery other water districts began testing that revealed tens of thousands of MTBE pollution cases across the United States.

Santa Monica also was booming in business at the time. The state of California enacted a law, effective January 1, 1999, that overrode Santa Monica's rent control ordinance by mandating vacancy decontrol. Landlords were reported to have raised rents so high that units remained vacant, requiring them to lower their rents to more marketable levels. Rent controls remained on inhabited units, leading to stories of landlords harassing existing tenants in order to make them leave so that higher rents could be charged.[20]

2000s

[edit]On July 16, 2003, George Russell Weller drove his Buick at speeds of up to 70 miles per hour through the busy downtown Farmers Market, which was held on a city street that was closed to vehicular traffic by temporary signage at each end. The 86-year-old driver killed 10 that day and injured 63, stopping only due to the Buick's engine and transmission being clogged with body parts.[21] The city vigorously fought against accepting its responsibility in causing the death and injuries of market patrons through the lack of any barricade. In the wake of numerous civil lawsuits filed against the City of Santa Monica and the company organizing the Farmer's Market, a new policy was adopted requiring portable concrete barricades to reliably block vehicle access for pedestrian street events.

Santa Monica passed a law in 2003 restricting the distribution of food to homeless people in the city. Some organizations have deliberately disobeyed these laws.

The increasingly upscale nature of the city – not just the northern part, which was always affluent, but the southern Ocean Park neighborhood as well which has become a favorite of those in the entertainment industry – has created some tensions between newcomers and longtime residents nostalgic for the more bohemian, countercultural past. Nevertheless, with the recent corporate additions of Yahoo! (2005) and Google (2006), gentrification continued.

During the 2000s, LA Metro developed plans to return rail transit to Santa Monica, which was gone after the dismantling of the Pacific Electric Railway during the 1960s. It developed two plans, including the Metro Expo Line and Metro Purple Line, both of which would extend into Santa Monica. The Purple Line was originally to be extended into Santa Monica, but was stopped due to legislative action. However, Democratic Congressman Henry Waxman, one of those who opposed the Purple Line's extension, eventually reconsidered extending the Purple Line into Santa Monica. The proposal to extend the Purple Line was described colloquially as the Subway to the Sea.

2010s

[edit]

On June 7, 2013, a killing spree occurred in several locations at or near the campus of Santa Monica College. The shooter, identified as 23-year-old John Zawahri, fired shots from an AR-15-type semiautomatic rifle, killing six people, including himself. The shootings started at Zawahri's father's house, where he fatally shot his father and brother after a domestic dispute, and afterwards, he set the home on fire. He then commandeered a passing vehicle and fired several shots at other vehicles, including a city bus and a police cruiser, killing two and wounding several others. Upon arriving at Santa Monica College, Zawahri shot and killed a woman outside and then fired 70 shots inside the college library, hitting no one. He was then shot by responding police officers after engaging them in a gunfight, later dying after being taken outside.[22][23][24]

In 2016, construction of the LA Metro E line was completed and it began servicing Santa Monica.[25]

2020s

[edit]Santa Monica experienced looting during the 2020 George Floyd protests.[26] By 2024, homelessness increasingly affected local businesses via reduced sales and increased crime.[27][28] Starting in the mid-2010s and continuing to the mid-2020s, the Third Street Promenade experienced vacancies due to high rents, the retail apocalypse, the COVID-19 pandemic, the homelessness crisis, rising inflation, and difficulty sub-dividing its large buildings. Third Street Promenade has also lost foot traffic and street performers.[29]

See also

[edit]- List of City of Santa Monica Designated Historic Landmarks

- Santa Monica City Council

- Arcadia Bandini de Stearns Baker

References

[edit]- ^ a b "City of Arcadia, CA". www.arcadiaca.gov. Retrieved January 8, 2023.

Bartolomea (her Spanish mission name), an indigenous Gabrieliño-Tongva Native American, was born around 1808 in an indigenous town called Comigranga, which was located around today's Santa Monica. She was taken away from her parents to live at the San Gabriel mission

- ^ A passage in time : the archaeology and history of the Santa Susana Pass State Historical Park, California. Richard Ciolek-Torrello. Tucson: Statistical Research. 2006. p. 65. ISBN 1-879442-89-2. OCLC 70910964.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ Archuleta, Daniel (October 29, 2012). "Letter: Tongva Park has a ring to it". Santa Monica Daily Press. Retrieved January 10, 2023.

- ^ a b c Paula A. Scott, Santa Monica: a history on the edge. Making of America series (Arcadia Publishing, 2004), 17–18.

- ^ "Kuruvungna Village Springs". Gabrielino-Tongva Springs Foundation. Retrieved February 19, 2024.

- ^ a b Handcock, Ralph, "Fabulous Boulevard", Funk & Wagnalls, 1949

- ^ a b "Venice History". www.westland.net.

- ^ Mark McIntire, Minorities and Racism[usurped], Free Venice Beachhead #126, June 1980.

- ^ "San Francisco Call 4 September 1912 — California Digital Newspaper Collection". cdnc.ucr.edu. Retrieved February 20, 2023.

- ^ Fogelson, Robert M. (1993). The fragmented metropolis: Los Angeles, 1850–1930. Berkeley: University of California Press. p. 200. ISBN 0-520-08230-3.

- ^ Hiney, Tom (1999). Raymond Chandler. Grove Press. p. 92. ISBN 9780802136374.

- ^ Herman, Arthur. Freedom's Forge: How American Business Produced Victory in World War II, pp. 202–3, Random House, New York, NY, 2012. ISBN 978-1-4000-6964-4.

- ^ Parker, Dana T. Building Victory: Aircraft Manufacturing in the Los Angeles Area in World War II, pp. 7–48., Cypress, CA, 2013. ISBN 978-0-9897906-0-4.

- ^ Zinzi, Janna A. (August 1, 2020). "The Tragic History of L.A.'s Black Family Beach Havens". Daily Beast. Retrieved August 1, 2020.

- ^ http://paleofuture.gizmodo.com/the-man-who-fought-cults-and-won-1634267961

- ^ a b https://www.thefix.com/content/aa-cults-synanon-legacy0009

- ^ "Copley: History". ketupa.net. Archived from the original on March 20, 2007. Retrieved March 7, 2007.

- ^ "Random Lengths News (www.randomlengthsnews.com)". randomlengthsnews.com. Archived from the original on August 5, 2007. Retrieved March 7, 2007.

- ^ "Easy Reader". hermosawave.net. Archived from the original on August 18, 2006. Retrieved January 15, 2020.

- ^ "NCPA - State and Local Issues - After Santa Monica Decontrolled Rents". Archived from the original on May 12, 2006. Retrieved February 14, 2005.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on July 17, 2012. Retrieved July 10, 2010.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ "Man opens fire at California school". CNN. June 7, 2013. Retrieved June 7, 2013.

- ^ "Five shot near Santa Monica College minutes after President Obama's motorcade passed by". New York Daily News. June 7, 2013. Retrieved June 7, 2013.

- ^ "Santa Monica shooting victim dies, bringing toll to 5". CNN. June 9, 2013. Retrieved July 9, 2013.

- ^ Nelson, Laura (February 26, 2016). "Metro Expo Line to begin service to Santa Monica on May 20". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved September 13, 2024.

- ^ "Santa Monica looting: Over 400 arrested, businesses damaged as vandals set fires near George Floyd protest". ABC7 Los Angeles. June 1, 2020. Retrieved September 13, 2024.

- ^ Team, FOX 11 Digital (August 30, 2024). "More Santa Monica businesses board up amid crime, homelessness: 'Mayor, we need your help'". FOX 11. Retrieved September 13, 2024.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Rambaldi, Camilla; Soto • •, Missael (May 29, 2024). "Third Street Promenade shop owners say homelessness hurts business". NBC Los Angeles. Retrieved September 13, 2024.

- ^ Mejia, Paula (May 21, 2024). "'Shocking': The fall of Third Street Promenade, Calif.'s once-vibrant outdoor mall". SFGate. Retrieved September 13, 2024.

- Luther A. Ingersoll, "Ingersoll's Century History, Santa Monica Bay Cities – Prefaced with a Brief History of the State of California, a Condensed History of Los Angeles County, 1542–1908; Supplemented with an Encyclopedia of Local Biography", ISBN 978-1-4086-2367-1, 2008

- Paula A. Scott, “Santa Monica: A History on the Edge”, Arcadia Publishing, ISBN 0-7385-2469-7, 2004

External links

[edit]- Imagine Santa Monica – Santa Monica Public Library's Digitized Historical Collections

- Tom Morello, Serj Tankian Break Law To Feed Homeless – MTV.com

- "Social Norms and Implications of Santa Monica's PEN (Public Electronic Network)"

- Yakety-Yak, Do Talk Back! Wired magazine article on PEN

- "Ocean Park Forward and Backward"

- American Grand Prix – includes map of racing route. Archived December 7, 2004, at the Wayback Machine

- (Tinder Box) Little Shop of Briars[dead link]

- (Tinder Box) A 75-Year Pipe Dream Archived September 27, 2007, at archive.today