History of Santa Maria, California

The history of Santa Maria, California, starts with the native Chumash people, who lived there for several thousand years before the Spanish Empire colonized the region in the 18th century. Later, it was a part of the Mexican Empire, California Republic, and finally, the United States. The city was incorporated in 1905, when it had a population of 3,000. As of the 2020 U.S. census, the population was 109,707.

18th century

[edit]

In 1769, Spanish explorer Gaspar de Portola explored the Santa Maria Valley on an expedition in California from San Diego to Monterey. The native inhabitants at the time were the Chumash people. They had established settlements in the valley and on the coast. The valley had rich resources of water and wild game. Spanish settlement around the area began in 1772, when they established Mission San Luis Obispo to the north, at a location that would become the city of San Luis Obispo. The Mission La Purisima Concepcion was established near the future site of Lompoc, southwest of the valley, in 1787. Spanish expeditions to Monterey traveled on a dirt road through the valley that would become the California Mission Trail. The trail linked all 21 of the eventual missions in California. The Spanish called the valley "El Llano Large de Laguna", or the "long valley of the lagoon".[1]

19th century

[edit]Under Mexico

[edit]In 1821, Mexico declared their independence from the Spanish Empire, and the land of the Santa Maria Valley became a part of Mexico. The California missions became secularized, and the missions' lands were "broken up into large ranchos and granted out for individual landownership." The grants were given to former Mexican soldiers and their descendants, for their service in the Mexican War of Independence. Many people came to the area hoping to get the free land. Santa Maria-style barbecue has its roots from these days. The first of these settlers were William Benjamin Foxen and his wife, Eduarda, who were granted the 8,874 acre Rancho Tinaquaic in 1837.[1]

Joining the United States

[edit]

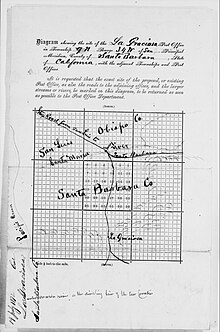

California eventually joined the United States as a territory. Settlers in the region were beginning to tap water by the time California became a state in 1850. Beans and grains were the most popular crops at that time. Enough settlers turned the Mission Trail from a dirt path into a stagecoach trail. The first town in the valley was La Graciosa, near present-day Orcutt. It had a school, and its post office, store, and stagecoach were located in one building. The town would later dissolve after the land was sold and the owners decided to redevelop.[2] In 1856, ranchero Juan Pacifico Ontiveros and his wife Martina bought the Rancho Tepesquet. They drove their 1,000 cattle from further south to the ranch. He named his house Santa Maria, after the Virgin Mary, and named a nearby waterway the Santa Maria Creek, later known as the Santa Maria River.[2]

George and Henry Stowell, were brothers who were some of the valley's original settlers. The Stowell family is "one of the largest and most influential families in the town's history". The two made their way to the West Coast in the early 1850s, working as excavators in Northern California, before moving south in the 1860s. The two lived in San Luis Obispo and other places in the area before settling in the valley; George bought 160 acres of farming land one mile south of what would later be Main Street. George's grandson, George Stowell Hobbs, was the city's longest serving-mayor at 22 years.[3]

After the federal government's Homestead Act of 1862, more people took the government's offer of settling on cheap land in the valley. By 1869, there were 100 settlers in the valley. In 1874, a town site was plotted, when the city was named Central City, or Grangeville. Four quadrants of land were put together to form the intersection of Broadway and Main Street, which became the town center.[3]

Notable figures

[edit]The four quadrants were owned by Isaac Fesler, Isaac Miller, John Thornburgh, and Rudolph D. Cook:[3]

- Isaac Fesler, who owned the northwest corner, moved to the city by wagon train in 1865. In the 1870s, he sold his land to the Kaiser Brothers, who ran a mercantile store for a few years before they sold their property to a bank, which would become the First Bank of Santa Maria. Another part would become a part of the Pacific Coast Railway.

- Isaac Miller owned the northeast corner. He devoted large portion of his land to fruit orchards, but the operation failed during a dry spell in the 1870s. He operated a business venture known as the Miller and Lovett store, which he sold and became Kriedal and Fliesher Merchandise.

- John Thornburgh moved to the city in 1870. Thornburgh set up one of the town's first co-operative stores at the intersection, which included the town's first post office. He also donated the land that the First Methodist Church was built on. His second wife, Minerva (nicknamed "Aunt Minerva") formed the Ladies Literary Society, which was renamed to the Minerva Library Club in 1906 in her honor. The club was "one of the oldest, continuously operating women's clubs in California".[4]

- Rudolph D. Cook made his way to the West Coast in the 1850s, and initially settled in Sonoma. In 1852, he built California's first threshing machine and harvest the first piece of grain grown in the state. In 1864, he lost his crops due to dry weather and headed to Los Angeles by wagon train. He heard about land available in the Santa Maria Valley, and moved there. He built the city's first house, and in 1870, funded the first school.

The streets of the intersection were 120 feet wide. The name of the town was first recorded as "Grangerville" at the Santa Barbara County seat 1875. The town later changed its name to Central City, because of its location between Guadalupe and Sisquoc, but they had to change their name by 1882 as their mail was getting sent to Central City, Colorado, which was already established. By 1882, the town had a blacksmith, wagon and machine shop, steam-fed mill, lumberyard, and the Hart House hotel, built by immigrant Reuben Hart.[2][3] The Hart House had a barbershop, reading room, retail shops, and a bar.[5]

Early pioneers to the town were immortalized in various street names, such as "Battles, Blosser, Cook, Fesler, Jones, Miller, Oakley, Stowell, Thornburgh, Miller, Tunnel, and a host of others". Some of the other settlers were:[3]

- Charles Bradley, who came to America in 1868. He settled at a site now known as Bradley Canyon, and moved to another site owned by T.A. Jones. Bradley's homesteading prospered, and he added on more land, become one of the most prosperous landowners in the valley with 2,720 acres. He was also one of the first president of the Bank of Santa Maria, and purchased the Hart House, renaming it the Bradley House. After he died, his family would become even wealthier once oil was discovered on their property.

- Garrett Blosser, born in 1869, who moved to Santa Maria when was a baby. He would be elected the city's constable in 1898, served as the deputy sheriff under Nat Stewart for 18 years, was the first city marshal, and was a member of the city's Hesperian Lodge, Fraternal Order of Eagles and Odd Fellows. When he died, the Santa Maria Times said he was "one of the valley's landmarks, so to speak, and helped build up the town in more ways than one."

- George Washington Battles came to the valley in the fall of 1868, after leading many cross-continental trips of those who were interested in joining the California Gold Rush. Battles organized a petition calling for the organization of the town's first school district. The county would not allow a school district until the town's citizens built a school house, obtained a teacher, and paid the teacher's salary for a year. The site for the school changed multiple times, but in 1870, Pleasant Valley School was founded, with 15 kids enrolling. The first teacher was Joel Miller.

- Samuel Jefferson Jones, moved from Ohio to California via the first transcontinental railroad in 1869. His hand drawn sketches and photographs of the valley are important historical references.

In 1875, the Ramona Foxen and her husband, Frederick Wickenden, established the Chapel of San Ramon and its cemetery on a knook overlooking the valley. The chapel would later be dedicated as a Santa Barbara County and California state landmark.[1]

Late century development

[edit]The city's first waterworks was built in 1880, and in 1882, the Pacific Coast Railway depot from San Luis Obispo to Central City was built. In 1882, the city changed their name to Santa Maria. By this time, various ethnic groups had immigrated to the area, including Spanish, Mexican, English, Scottish, Irish, Japanese, Swiss-Italian, and Portuguese people. Advanced irrigation methods lead to the growing of "flower seeds, strawberries, lettuce, broccoli, cauliflower, and many other fruits and vegetables".[2]

One of the early drivers of the town's economy, besides agriculture and oil, was the Betteravia Sugar Mill, which refined sugar beets. The town of Betteravia, now a ghost town, was a company town, built for the factory and the workers of the Union Sugar Factory.[3] Union Sugar was incorporated in September 1897 by a union of farmers from San Luis Obispo and Santa Barbara Counties,[6] and the first sugar from the factory was produced on September 20, 1899.[7] At one time, the town contained 60 cottages, a church, a hotel, a church, and a schoolhouse.[3] In the early 1900s, many pioneers from Japan moved to Santa Maria to work in the industry, in spite of America's anti-Asian immigration laws.[8] The Union Sugar Factory closed the factory in early 1960s, and the facility was shuttered after an explosion in 1988. The remnants of the town are "barely visible today".[3]

The Santa Maria Times formed in 1882.[9] The Bank of Santa Maria was founded in 1890[10] or 1906,[4] and later became the Security-First National Bank. It was demolished in the late 1960s and turned into a gas station.[4]

In March 1891, the California State Legislature passed the Union High School Act, which gave the right for adjoining districts to create a "union high school" district. The Santa Maria Union High School, covering Santa Maria, Gary, Guadalupe, Los Alamos, Orcutt, and Sisquoc, opened for the 1891 fall semester in a brick grammar school on Main Street. 44 students were enrolled then, 14 freshmen, 9 "middlers", 18 juniors and 3 seniors. The first principal was George Russell, who was paid $80 per month. The numbers of students began growing, so in 1902, more than $400,000 in bonds were passed to tear down the building and created new school buildings. The school became accredited by the California State University that year. In 1903, the school's colors (red and white) and mascot (saints) were adopted. That year, the first sport at the school started, baseball. Additional construction was done in December 1905, doubling the school's size.[11]

20th century

[edit]

In 1901, Pinal Oil Company was founded. It had 22 oil wells in production by 1903, being the major oil company in the valley. In 1911, it merged with Dome Oil Company to form Pinal Dome Oil Company, which was bought out by Union Oil in 1917.[12] In 1902, the Southern Pacific Railroad connected Santa Maria to Los Angeles.[2] In 1907, the Santa Maria Gas & Power Company was formed.[7] The Santa Maria Valley Railroad was constructed in 1912, which linked the oilfields at Guadalipe and Roadamite.[2]

In 1905, around 3,000 people lived there. A special election held on September 12, 1905, determined that the city should be incorporated. The city council trustees were chosen to be Alvin W. Cox, Emmett T. Bryant, Reuben Hart, Sam Fliesher, and William Mead; the city clerk was chosen to be John E. Walker. Their first meeting on September 21 discussed Ordinance No. 1, regarding liquor licenses. The second ordinance regarded petitions to open two saloons, the appointment of Matt Jesse to night patrolman, as well as Joseph Spriggs to the office of Pound Master. Succeeding ordinances determined the board's meeting dates, speed limits for riding or driving, the city employee's salaries, the corporation's seal, the amount of bonds for officers, details regarding license taxes, and laws regarding animals. For salaries, the city clerk was given $45, the city attorney $35, the city marshal $75 and 50% percent of "all taxes and license taxes collected". The first meeting of the trustees was on October 24, regarding the licensing of merry-go-rounds and the duties of the city marshal. There was an early conflict regarding business licenses, and various business owners found themselves unable to pay the license fee. Protestors "engulfed the board" for several meetings. Bryant resigned from the board in April 1906, and was succeeded by William C. Oakley. Oakley remained there until he was succeeded by R.J. Stephenson in 1908. Oakley returned to the board in 1912, and was elected by the other trustees to become the city's first mayor in 1918. He resigned in January 1920.[13]

Frank McCoy, who was president of the Union Sugar Company, retired from his position at the company in 1915. On May 16, 1917, he opened the Santa Maria Inn, which became an acclaimed establishment that hosted "dignitaries, presidents, and Hollywood royalty" as they "made their way north for business or vacations". The building opened with 24 rooms, which was expanded to 85 rooms in 1928. The construction of Highway 101 took a portion of the inn's business, and the inn closed. It was purchased, renovated, and reopened in the 1980s. It was designated as a city landmark in 1985.[3][14]

In 1921, the Santa Maria Union High School was demolished, and rebuilt by 1925. A 100-foot bell tower was built with the new campus, which was removed in 1963 to comply with California earthquake-safety requirements.[15] In 1926, Captain John Hancock started the city's first radio station, operating from the Santa Maria Valley Railway office building.[16] By 1929, the city's population had reached 7,097.[7] The El Camino Middle School was established in 1931.[15] Captain George Allan Hancock founded the Hancock College of Aeronautics in 1929, which eventually teach ground and flight training to thousands of pilots during World War II. The site was later occupied by Santa Maria Community College, which would change its name to Allan Hancock College.[17] The City Hall was dedicated in 1934.[2]

On July 14, 1935, there was a battle on the Santa Maria River between two factions of the U.S. military.[18]

The Santa Maria Public Airport was founded after World War II, and acquired by the city for commercial flight operations in 1947. The current site was originally the Santa Maria Army Air Base.[19] During the war, the U.S. government forcibly interned Japanese citizens into concentration camps. Most of the Japanese in Santa Maria were moved to the Gila River War Relocation Center near Phoenix, Arizona. Those whose families had moved to Santa Maria because of the sugar industry, did not come back in great numbers.[8] On January 13, 1945, a P-38 airplane on routine maneuvers crashed into Rusconi's Cafe, and tore off the roof of the Economy Drug Store. Four people were killed.[7]

In July 1947, Jim Gamble created the town's first semiprofessional football team, the Santa Maria Valley Athletic Club's Redskins. By the time the club disbanded in 1953, the Redskins had won 30 games, lost 30, and tied 2.[20]

The old fire station, located behind the City Hall, burned down in May 1956, at a loss of $100,000. The fire station's equipment and its historical data were lost.[4]

The mayor from 1956 to 1960 was Curtis Tunnell, who worked to improve the downtown area. The 100 Block of East Main Street downtown was known as Whiskey Row, a strip of bars, card rooms, and pool halls. Tunnell tried to negotiate with the "11 or 12" owners of the business to rehabilitate themselves, and was unsuccessful. At a council meeting in 1959, Tunnell declared action against the Row, calling it an "eyesore". In the following years, it was declared a redevelopment area, and the property was purchased by the government. After much litigation, the buildings were torn down in January 1963.[7][21] The name of the area would be changed to Central Plaza in March 1966, named by chairman of the Council Advisory Committee, John Melby.[16]

A Jewish synagogue was built in 1963.[7] Ernest Righetti High School opened in 1963.[citation needed] St. Joseph High School opened in 1964.[22] The television news station, KCOY-TV, started in March 1964.[16] In 1968, Union Sugar Company announced the closing of Betteravia.[7]

The city's second semipro football team, the Santa Maria Football Club, was founded in 1967. In 1968, they were renamed to the Santa Maria Hawks. In 1969, they were contracted to play as extras in the movie M*A*S*H. They disbanded in 1970.[20]

In 1974, the Santa Maria Valley Historical Society Museum was opened at its current site.[20] The Santa Maria Town Center opened in 1976.[23] The Santa Maria Regional Transit started in 1978. The Santa Maria Valley AVA started in 1981.[citation needed] In 1998, the city won an All-America City Award from the National Civic League, honoring the city as a "better place to live and work".[17]

21st century

[edit]The trial of Michael Jackson was moved from Santa Barbara to Santa Maria in 2003, and took place in 2005.[24][25]

Pioneer Valley High School opened in 2004.[26]

The city celebrated its centennial on September 12, 2005.[17]

In 2010, the population was 99,533. The 2020 census showed that Santa Maria lead the county in population growth since the 2010 census, with 10,154 moving in during the 2010s.[27] As of 2020, the population was 109,707.[28] In 2020, the city was affected by the COVID-19 pandemic. By April 29, the city had only one confirmed COVID-19 case.[29] By July 29, the city had 2,677 confirmed cases.[30] The city saw a large spike in rent prices after the pandemic.[31]

In 2021, the city created a general plan for the city's growth over the next 25 to 30 years, preparing for 30,000 new residents.[32] A preferred land use plan was adopted in 2023, creating a study on whether or not the city should annex a large portion of agricultural land.[33] In the early 2020s, there was a surge in the amount of new housing units in the city, as well as redevelopment of the downtown.[34][35]

In 2023, it was publicized that the Santa Maria Public Airport had contaminated its subsurface soil for the previous 42 years.[36]

On September 25, 2024, Nathaniel McGuire, aged 20, walked into the Santa Maria Courthouse on the day of his arraignment for a firearms charge, and threw a bag with an explosive through the building, injuring several people.[37]

References

[edit]- ^ a b c Montoya 2011, p. 8.

- ^ a b c d e f g Montoya 2011, p. 9.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i "Interactive Map: The history of the Santa Maria Valley is all around us. Just read the (street) signs". Lompoc Record. 2019-06-17. Retrieved 2024-01-22.

- ^ a b c d "Photos: See what the Elks Parade looked like in the 1950s". KSBY News. 2023-06-03. Retrieved 2024-01-22.

- ^ Montoya 2011, p. 22.

- ^ Montoya 2011, p. 44.

- ^ a b c d e f g "January highlights in history: Santa Maria High takes shape, Whiskey Row demolished | Shirley Contreras". Lompoc Record. 2023-01-07. Retrieved 2024-01-23.

- ^ a b O'Connor, Taylor. "Cultural cache". Santa Maria Sun. Retrieved 2024-01-22.

- ^ "Shirley Contreras: Important dates in April from 1882 to 2006". Santa Maria Times. 2019-03-31. Retrieved 2024-01-23.

- ^ Montoya 2011, p. 19.

- ^ "Sports added at Santa Maria Union High School | Heart of the Valley". Santa Maria Times. 2023-07-23. Retrieved 2024-01-22.

- ^ Montoya 2011, p. 17.

- ^ "City government in Santa Maria started in 1905 | Heart of the Valley". Santa Maria Times. 2022-09-10. Retrieved 2024-01-22.

- ^ Montoya 2011, p. 35.

- ^ a b Montoya 2011, p. 36.

- ^ a b c "Important Santa Maria Valley history dates in March | Heart of the Valley". Santa Maria Times. 2023-03-05. Retrieved 2024-01-23.

- ^ a b c Montoya 2011, p. 10.

- ^ Contreras, Shirley (2023-05-13). "Santa Maria River was 'battlefield' for large field maneuver in 1935 | Heart of the Valley". Santa Maria Times. Retrieved 2024-01-23.

- ^ O'Connor, Taylor. "Foam legacy". Santa Maria Sun. Retrieved 2024-01-23.

- ^ a b c "Redskins, Hawks: The history of Santa Maria's semipro football teams". Santa Maria Times. 2023-08-19. Retrieved 2024-01-22.

- ^ "A mayor's crusade to 'dry up' Whiskey Row | Heart of the Valley". Santa Maria Times. 2023-08-06. Retrieved 2024-01-22.

- ^ Bullock, Brian (2015-03-27). "St. Joseph High celebrates 50 years of education, inspiration". Santa Maria Times. Retrieved 2024-01-23.

- ^ "Santa Maria Town Center Mall Opens With Sears, Gottschalk's". Los Angeles Times. 12 September 1976. p. i10. ProQuest 158015363.

- ^ Overend, William; Chong, Jia-Rui (2003-12-06). "Jackson Case Is Moved to Santa Maria". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 2024-01-23.

- ^ Minsky, Dave (2019-11-05). "Santa Maria courtroom that housed Michael Jackson trial will be modified for MS-13 trial". Santa Maria Times. Retrieved 2024-01-23.

- ^ "Pioneer Valley High School". Santa Maria Times. 2004-08-09. Retrieved 2024-01-23.

- ^ Hodgson, Mike (2021-11-22). "Census shows Santa Maria led Santa Barbara County in population growth". Santa Maria Times. Retrieved 2024-01-23.

- ^ "U.S. Census Bureau QuickFacts: Santa Maria city, California". www.census.gov. Retrieved 2024-01-23.

- ^ Smith, Delaney (2020-04-30). "Eighth COVID-19 Death in Santa Barbara County, First Community Testing Site to Open". The Santa Barbara Independent. Retrieved 2024-01-23.

- ^ "85 COVID-19 cases linked to Alco Harvesting outbreak in Santa Maria". KSBY News. 2020-07-29. Retrieved 2024-01-23.

- ^ CalMatters, Ben Christopher (2023-07-29). "Some of California's 'Cheapest' Cities Have Seen the Biggest Rent Hikes, Including Santa Maria | Local News". Noozhawk. Retrieved 2024-01-23.

- ^ "Future planning model should set Santa Maria up as premiere city to live, work, play | Guest Commentary". Santa Maria Times. 2023-11-25. Retrieved 2024-01-23.

- ^ Writer, Mike Hodgson Contributing (2023-12-08). "Santa Maria council adopts preferred land use plan on split vote". Santa Maria Times. Retrieved 2024-01-23.

- ^ "Housing growth surges in SLO and Santa Barbara counties". Cal Coast News. 2023-05-03. Retrieved 2024-01-23.

- ^ "Santa Maria's downtown revitalization will be transformative | Guest Commentary". Santa Maria Times. 2023-02-14. Retrieved 2024-01-23.

- ^ Welsh, Nick (2023-03-08). "Major Toxic Contamination Problem at Santa Maria Airport?". The Santa Barbara Independent. Retrieved 2024-01-23.

- ^ Quednow, Cheri Mossburg, Cindy Von (2024-09-25). "Man facing firearms charge threw bag with explosive inside California courthouse, injuring several people, officials say". CNN. Retrieved 2024-09-27.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

Sources

[edit]- Montoya, Carina Monica (2011). Santa Maria Valley, Arcadia Publishing. ISBN 9780738588803