History of Northern Epirus from 1913 to 1921

The history of Northern Epirus from 1913 to 1921 is characterized by the desire for "enosis," or union with the Greek national state, among the Greek minority residing in this region of southern Albania. Additionally, the irredentist aspirations of the Hellenic kingdom to annex the region are noteworthy.

During the First Balkan War, Northern Epirus, which was home to a significant Orthodox community that spoke either Greek or Albanian, was occupied along with Southern Epirus by the victorious Greek army in opposition to the Ottoman Empire. Athens sought to annex these territories. However, Italy and Austria-Hungary opposed this, and the Treaty of Florence in 1913 awarded Northern Epirus to the newly established Principality of Albania, which had a predominantly Muslim population. Consequently, the Greek army withdrew from the region, but Christian Epirotes rejected the international decision and proceeded to establish, with Greece's tacit support, an autonomous government[note 1] in Argyrókastro (Gjirokastër).

As a consequence of the prevailing instability in Albania, the autonomy of Northern Epirus was ultimately validated by the major powers through the formalization of the Protocol of Corfu on 17 May 1914. The agreement recognized the specific characteristics of the Epirotes and their right to have their administration and government under Albanian sovereignty. However, this agreement was never fully implemented due to the collapse of the Albanian government in August. Prince Wilhelm of Wied, who had been elected sovereign of the country in February, returned to Germany in September.

In the aftermath of the onset of World War I in October 1914, the Kingdom of Greece proceeded to reoccupy the region. Nevertheless, Athens' ambivalent stance toward the Central Powers during the Great War prompted France and Italy to invade Northern Epirus in September 1916. After the First World War, the Tittoni-Venizélos agreement anticipated the region's incorporation into Greece. However, a shift in the political leadership in Rome and Greece's military conflicts with Mustafa Kemal's Turkey ultimately benefited Albania, which finally acquired the region on 9 November 1920.

Region population

[edit]

The last census conducted by the Ottoman Empire in Northern Epirus in 1908 enumerated 128,000 Orthodox subjects and 95,000 Muslims.[1] Among the Christian population, 30,000 to 47,000 individuals spoke only modern Greek. The remainder of the community was bilingual, with their vernacular language being an Albanian dialect. However, they were educated in Greek, which was also used in cultural, commercial, and economic activities.[2] Additionally, a portion of the Albanian-speaking Orthodox population exhibited a pronounced sense of Greek national identity[note 2] and were the initial supporters of the Epirote autonomy movement.[3]

In the region, the opposition between Muslim and Christian populations was a long-standing and historically entrenched phenomenon. In September 1906, Muslim nationalists assassinated the Orthodox Metropolitan Photios of Korytsá, accusing him of being an agent of Panhellenism.[4] This act resulted in heightened tensions between communities, with even Albanian Christian nationalists in the diaspora not immune to its effects.[5] In this context, the support of Orthodox Epirotes for an Albanian government led exclusively by Muslim leaders (who were in opposition to each other) was far from unanimous in 1914.[6]

Epirus in the Balkan Wars

[edit]Greece invades Epirus

[edit]

In March 1913, the Greek army, engaged in combat with the Ottoman Empire in the First Balkan War, breached Turkish fortifications in Epirus at the Battle of Bizani. They subsequently captured the city of Ioannina and advanced further north.[7] In November 1912, a few months before the Battle of Bizani, the town of Himara, situated on the Ionian Sea, was captured by Greek forces. This was achieved by Spyros Spyromilios, a native of the region and a Gendarmerie officer, who landed there and took control after a brief battle.[8] Following the conclusion of the First Balkan War, the majority of historical Epirus was under Greek control, extending from the Ceraunian Mountains above Himara to Lake Prespa to the east.[note 3]

Meanwhile, the Albanian nation was undergoing a process of awakening. On 28 November 1912, Ismail Qemali, a prominent politician, proclaimed Albania's independence in Vlora, while a provisional government was established. However, this government was only able to establish itself in the Vlora region. In Durazzo (now Durrës), Ottoman General Essad Pasha formed a "Central Albanian Senate," and tribal leaders continued to support the idea of an Ottoman government.[6] The majority of the territory that would later form the Albanian state was occupied by Greece (in the south) and Serbia (in the north).[9]

Delimitation of the Greek-Albanian border

[edit]

In the aftermath of the First Balkan War, the concept of an autonomous Albanian state garnered significant support from the major European powers, particularly Austria-Hungary and Italy.[10] However, these two countries sought to exert control over Albania, which, according to Italian Foreign Minister Tommaso Tittoni, would afford whoever possessed it "undeniable supremacy over the Adriatic." The annexation of Shkodër by Serbia and the possibility of the Greek border extending just a few kilometers from Vlora greatly displeased these powers.[9][11]

In September 1913, an international commission was constituted to delimit the border between Greece and Albania. The commission, overseen by the great powers, rapidly became divided between Italian and Austro-Hungarian delegates on one side and delegates from the Triple Entente (France, the United Kingdom, and Russia) on the other. The former group considered the region's inhabitants to be Albanian, whereas the latter argued that, although some villages had older Albanian-speaking generations, the entire younger generation exhibited Greek cultural, emotional, and aspirational traits.[12] Ultimately, the Italian-Austro-Hungarian perspective prevailed.

Protocol of Florence

[edit]

Notwithstanding official protests from Athens, the Treaty of Florence, signed on 17 December 1913, awarded the entirety of Northern Epirus to the Principality of Albania. Following the signing of the document, representatives of the Great Powers delivered a note to the Greek government, requesting the withdrawal of its military from the region. Greek Prime Minister Elefthérios Venizélos complied with this request, in the hope of gaining favor with the Powers and securing their support in the issue of sovereignty over the North Aegean islands, which were contested by the Ottoman Empire.[13][note 4]

Consequences of the Protocol of Florence

[edit]Northern Epirus declares its independence

[edit]The transfer of Northern Epirus to Albania was met with immediate and widespread opposition among the region's Christian population. Those who advocated for "enosis" (union with the Hellenic kingdom) perceived the Elefthérios Venizélos government as having betrayed them by refusing to provide military support. Furthermore, the gradual withdrawal of the Greek army from the region posed a risk of allowing Albanian forces to gain control of Northern Epirus. To prevent this, Epirote irredentists sought to assert their identity and establish an autonomous government.[14][15]

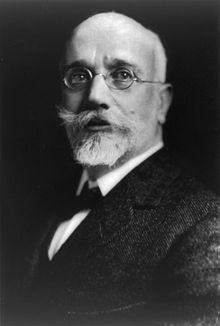

Subsequently, an autonomous Republic[note 1] of Northern Epirus was proclaimed on 28 February 1914, in Argyrókastro, following negotiations between representatives of the region's populations and Georgios Christákis-Zográfos, a politician from Lunxhëri and former Greek foreign minister. This was followed by the formation of a provisional government to support the new state's objectives.[14][16]

Georgios Christakis-Zografos was appointed as the provisional government's president. In his address on 2 March (the date of the official declaration of independence of Northern Epirus),[17] he elucidated that the national aspirations of the Epirotes had been entirely disregarded, and that the major powers had not only rejected the prospect of autonomy within the principality of Albania but also declined to guarantee the region's population their most fundamental rights.[14] Nevertheless, the politician concluded that the Epirotes would not acquiesce to the fate imposed upon them by the powers:

By the inalienable rights of every people, the desire of the great powers to create, for Albania, a valid and respected title to dominate our land and subjugate us is powerless in the face of the fundamentals of divine and human justice. Greece also has no right to continue its occupation of our territory simply to betray us against our will to a foreign tyrant. Free from all ties, unable to live united with Albania under these conditions, Northern Epirus proclaims its independence and calls on its citizens to make all necessary sacrifices to defend the integrity of its territory and its freedoms against all attacks, wherever they come from.[18]

The newly established state promptly adopted a series of national symbols. Among these was a flag that was a variation of the Greek banner, featuring a white cross on a blue background and a black two-headed Byzantine eagle.[19]

In the days following the declaration of independence, Alexandros Karapanos, a nephew of Zográfos and future member of parliament for Arta (in Greece),[20] was appointed to the role of foreign minister of the newly formed republic. Colonel Dimitrios Doulis, hailing from Niš, relinquished his post in the Greek army to assume the role of military minister in Epirus. He was able to rapidly assemble an army of 5,000 volunteers.[21] The local bishop, Monsignor Basil, assumed responsibility for the ministries of religion and justice. Approximately 30 Greek officers of Epirote origin, in addition to regular soldiers, defected from the Hellenic army to join the revolutionaries. In due course, armed groups such as Spyros Spyromilios' Sacred Band, which was established in the Himara region,[20] were formed to repel any incursions into the territory of the autonomous republic. The first districts to join the Epirote government outside Argyrokastro were those of Himara, Aghioi Saranta, and Përmet.[22]

Greece evacuates the region

[edit]

The Greek government was hesitant to extend its support to the insurgents due to concerns about potential displeasure from the major global powers. The gradual withdrawal of Greek troops, which commenced in March, persisted until 28 April, when the last foreign military personnel had been evacuated from the region.[20] In official statements, the Greek government discouraged the Epirotes from resisting and reassured the population that the great powers and the International Control Commission—an organization created by the powers to ensure peace and security in the region—were prepared to guarantee their rights. Subsequently, following the Argyrókastro declaration, Georgios Christakis-Zografos dispatched a missive to local representatives in Korytsá, wherein he exhorted them to align themselves with the movement. However, the Greek military commander in the city, Colonel Kontoulis, was unwavering in his adherence to the directives he had received from his superiors. He proceeded to declare martial law and issued a threat of lethal force against anyone who displayed the Northern Epirus flag. Consequently, when the bishop of Kolonjë, who would later become Spyridon I of Athens, proclaimed autonomy, Kontoulis promptly arrested and expelled him.[23][24]

On 1 March, Kontoulis relinquished control to the recently constituted Albanian gendarmerie, which was predominantly comprised of erstwhile Ottoman army deserters under the command of Dutch and Austrian officers.[22] On 9 March, the Greek navy implemented a blockade of the port of Aghioi Saranta, one of the inaugural municipalities to embrace the autonomist movement.[25] A series of isolated incidents transpired between Greek army units and Epirote insurgents, resulting in a handful of casualties on both sides.[26]

Between negotiations and armed conflict

[edit]With the withdrawal of Greek troops from the region, armed conflict erupted between the loyalist Albanian forces and the Epirote autonomists. In the areas of Himara, Aghioi Saranta, Argyrókastro, and Dhelvinion, the uprising spread in the days following the declaration of independence. Autonomist forces were able to halt the gendarmerie and irregular Albanian units.[23][24] However, Georgios Christakis-Zografos was aware that the great powers were unwilling to allow the annexation of Northern Epirus by Greece. Therefore, he proposed three diplomatic solutions to resolve the conflict:

- Complete autonomy for Epirus under the nominal sovereignty of an Albanian prince;

- Administrative and cantonal autonomy based on the Swiss model;

- Direct control and administration by the European great powers.[22]

A few days later, on 11 March, a provisional settlement of the conflict was negotiated by Dutch Colonel Thomson in Corfu. The Albanian authorities were amenable to the establishment of an autonomous government with constrained powers. However, the Epirote representative Alexandros Karapanos advocated for comprehensive autonomy, a position that was rebuffed by the delegates representing the Durazzo government. Consequently, the negotiations reached an impasse.[20][23] Concurrently, Epirote bands advanced towards Ersekë before directing their course towards Frashër and Korytsá.[27]

At that juncture, the autonomous government exercised control over the overwhelming majority of the insurgents' claimed territory, except for Korytsá. On 22 March, a Sacred Band from Bilisht reached the outskirts of Korytsá and joined the local guerrillas before engaging in intense street combat within the city. For several days, the autonomist units were able to gain control of the town, but Albanian reinforcements arrived on 27 March, resulting in Korytsá being returned to the control of the Albanian gendarmerie.[23][24]

The International Control Commission (ICC) resolved to intervene in the conflict to halt the escalation of violence and prevent the further spread of armed conflict. On 6 May, the Commission contacted Geórgios Christákis-Zográfos to initiate negotiations on a new basis. The politician accepted the proposal, and an armistice was reached the following day. However, by the time the ceasefire took effect, Northern Epirote forces had already occupied the heights overlooking Korytsá, thereby rendering the surrender of the city's Albanian garrison imminent.[28]

Recognition of autonomy and Albanian Civil War

[edit]The Protocol of Corfu

[edit]

Subsequently, new negotiations were conducted in Corfu. On 17 May 1914, representatives of the Albanian and Epirote communities signed an agreement known as the Protocol of Corfu. By the terms of this treaty, the provinces of Korytsá and Argyrókastro, which constituted Northern Epirus, were to be granted complete autonomy (as a corpus separatum) under the nominal sovereignty of Prince Wilhelm of Wied.[20][28] The Albanian government was to appoint and dismiss governors and senior officials, with due consideration for the will of the region's inhabitants. Other stipulations of the treaty included the proportional recruitment of Epirotes into the local gendarmerie and the limitation of conscription to individuals hailing from the region.[20] In Orthodox schools, the Greek language was to be the sole language of instruction, except for the initial three years, during which Albanian was to be taught. However, in public affairs, both languages were to be treated equally, including in matters of justice and electoral councils. Furthermore, the privileges previously granted to the city of Himara by the Ottomans were to be renewed, and a foreigner was to be appointed as "captain" (i.e., governor) for ten years.[29]

The protocol was formally adopted by representatives of the major powers in Athens on 18 June and by the Albanian government on 23 June.[30] An assembly of Epirote delegates convened in Dhelvinion also endorsed it, despite objections from Himara's representatives, who advocated enosis (union with Greece) as the sole viable solution for Northern Epirus.[31] On 8 July, the cities of Tepelen and Korytsá came under the control of the autonomous government.[20]

The instability in Albania and Greece's return

[edit]In the aftermath of the outbreak of World War I, Albania was beset by a period of political instability and chaos. The country was thus divided into several regional governments, each of which was in opposition to the others. As a result, the Corfu Protocol proved ineffective in restoring peace in Epirus, and sporadic armed conflicts persisted.[32] On 3 September, Prince Wilhelm of Wied and his family opted to leave Albania. In the following days, an Epirote unit, operating without the approval of the autonomous government, attacked the Albanian garrison in Berat and briefly captured the citadel. In response, Albanian troops loyal to Essad Pasha conducted small-scale military operations.[33]

The government of Eleftherios Venizelos in Greece was preoccupied with the instability of Albania, apprehending the possibility of a broader conflict as a consequence. Interethnic massacres targeting both Christians and Muslims occurred, resulting in the flight of numerous Epirotes to Greece.[34] Following the granting of approval by the Great Powers, which underscored the provisional nature of Greece's intervention rights, Athens deployed its military forces into Northern Epirus on 27 October 1914.[35] In the subsequent days, Italy capitalized on the circumstances to intervene on Albanian soil, occupying Vlora and the island of Sazan, situated in the Otranto Strait region, which is of strategic importance.[36]

In light of the return of the Greek army and the successful conclusion of the enosis (union with Greece), the representatives of the autonomous Northern Epirus Republic proceeded to dissolve the institutional framework they had established. Notably, Georgios Christakis-Zografos, the former leader of the autonomists, resumed his role as Greece's Foreign Minister shortly thereafter.[37]

The return of the Greeks was not universally welcomed in the region. In the district of Korçë, Albanian patriots initiated efforts to reintegrate their territory into Albania. Among the insurgents were both Muslims (such as band leader Salih Budka) and Orthodox Albanians[note 5] (like Themistokli Gërmenji).[38]

Northern Epirus during World War I

[edit]The Greek occupation (October 1914 – September 1916)

[edit]

As the First World War was being fought in the Balkans, Greece, Italy, and the countries allied with them decided that the fate of Northern Epirus would be decided after the conflict had ended. However, in August 1915, Eleftherios Venizelos proclaimed before the Hellenic Parliament that it would be a "colossal mistake" if the region were to be separated from the rest of Greece.[39]

Following the dismissal of the Prime Minister in October 1915, King Constantine I and his newly appointed government were resolute in their intention to exploit the prevailing international circumstances to formally incorporate the region into Greece. In December 1915, the inhabitants of Northern Epirus participated in the Greek parliamentary elections, electing 19 representatives to the Athens Assembly. In March of the following year, the union of the region with Greece was formally proclaimed, and the territory was divided into two prefectures: Argyrókastro and Korçë.[39][40]

From Franco-Italian occupation to Venizelos' return to Athens

[edit]The cooling of diplomatic relations between Greece and the Entente powers, along with the outbreak of the National Schism in Greece, resulted in further upheaval in Northern Epirus. In September 1916, France and Italy decided to militarily occupy the region and expel Greek royalist troops. Rome invaded the Argyrokastro prefecture, swiftly expelling those considered supporters of Hellenism. The Orthodox Metropolitan Vasileios of Dryinoupolis was expelled from his diocese, and ninety Greek leaders from the Himara region (including the mayor) were deported to the island of Favignana or Libya.[41]

Meanwhile, France contemplated replacing Greek royalist officials in the Korçë district with Venizelists. However, as anarchy intensified, they opted to exert more direct control.[42][43] Subsequently, under the direction of General Maurice Sarrail and his representative Colonel Descoins, the city and its surrounding areas were granted autonomous institutions, resulting in the formation of the "Republic of Korçë" (or "Republic of Kortcha"). In this newly established political entity, the Muslim population, which constituted the majority at 122,315 individuals, was afforded equal representation with the Christian population, which numbered 82,245.[44] Albanian was designated as the sole official language,[45] and Greek schools were closed.[46]

The overthrow of King Constantine I and Greece's official entry into the war on the Allies' side in June 1917 enabled Athens to reassert control over Epirus. Upon his return to power, Venizelos was able to secure the gradual withdrawal of Italian forces from the southern part of the region (which had been officially designated Greek in 1913).[47] However, despite the objections of the Greek Prime Minister, Rome persisted in its occupation of the Argyrókastro prefecture (which was officially designated Albanian in 1913).[48] Concerning the "Republic of Korçë," its autonomy was significantly curtailed by the French on 27 September 1917, and it was ultimately dissolved on 16 February 1918.[49]

From the Peace Conference to the Congress of Lushnjë

[edit]Northern Epirus and Albania at the end of the Great War

[edit]Upon the conclusion of World War I in November 1918, Northern Epirus became the subject of territorial aspirations on the part of at least four countries. In addition to Albania, which had been allocated the region before the war, Greece asserted its claim, citing historical and cultural ties with the population. Italy sought control over a portion of the territory to enhance its management of the Adriatic Sea. France, or more specifically the French military, aimed to leverage its presence in Korçë to exert influence over the Balkans.[50][51]

These conflicting assertions gave rise to considerable tension among the various powers involved.[52] Furthermore, they incited outrage among Albanian nationalists, who were already displeased by the deployment of Serbo-Croatian troops in northern Albania (specifically, in the Shkodër region).[50] Consequently, the Northern Epirus issue emerged as a particularly contentious topic during the Paris Peace Conference of 1919.

Venizelos' attempt to convince the Peace Conference

[edit]

Before the convening of the Peace Conference, Greek Prime Minister Eleftherios Venizelos articulated his country's claims to the Allies in a memorandum dated 30 December 1918. Among the territories that Venizelos sought for Greece, Northern Epirus, with its population of 151,000 Orthodox Christians, occupied a prominent position. Nevertheless, Venizelos was amenable to relinquishing a portion of the region, such as the Tepelen area, in exchange for retaining the majority of it. To rebut the assertion that the Greek population in Albania spoke primarily Albanian, he invoked the precedent of Alsace-Lorraine, citing the German argument that linguistic affiliation should determine regional boundaries. French by choice for the French, but linguistically German for the Germans. Venizelos observed that the leaders of the Greek War of Independence and members of his government, such as General Danglis and Admiral Koundouriotis, had Albanian as their mother tongue but still identified as Greek.[53][note 6]

During the conference, a specific committee, the "Greek Affairs Committee," chaired by Jules Cambon, undertook a detailed examination of the issue. Italy expressed opposition to Venizelos' stance, particularly about Northern Epirus, whereas France offered unreserved support for the Greek Prime Minister. The United Kingdom and the United States adopted a neutral stance. Venizelos invoked an argument reminiscent of President Wilson's assertion of the will of the people. He reminded the committee that in 1914, an autonomous government had been established in the region, expressing its desire to be Greek. Additionally, he presented an economic argument, claiming that Northern Epirus was more oriented towards Greece than Albania.[54]

On 29 July 1919, Eleftherios Venizelos and Italian Foreign Minister Tommaso Tittoni entered into a confidential agreement. The agreement resolved outstanding issues between the two countries and ceded Northern Epirus to Greece. In exchange, Greece promised to support Italy's claims over the remainder of Albania. On 14 January 1920, a session of the Peace Conference, presided over by Georges Clemenceau, ratified the Tittoni-Venizelos agreement, stipulating that its implementation would depend on the resolution of the conflict between Italy and Yugoslavia.[55][56]

The Lushnjë Congress and the Albanian reaction

[edit]

The Albanian delegates, unable to be heard by the representatives of the Great Powers and discredited by the division of their leaders,[note 7] sought a compromise with the Allies. Nevertheless, this strategy resulted in the alienation of nationalists within their own country, who were already incensed by the disclosure of the clauses of the 1915 Treaty of London, which sought to dismantle Albania in favor of its neighbors. From 21 January to 9 February 1920, a national congress was convened in Lushnjë, central Albania. There, fifty-six delegates, some of whom were from Korçë and Vlora, established the framework for a new government.[57]

On 29 January, the Congress submitted an official protest to the Peace Conference and Rome, denouncing the powers' attitude. The Albanian delegates condemned plans to partition their country and rejected any idea of an Italian protectorate. They informed the powers of their people's determination to fight for Albania's complete independence by any means necessary. Finally, they sent new delegates to Paris, led by Orthodox Christian Pandeli Evangjeli, to defend Albania's national interests.[57]

Albania establishing in the region

[edit]The Albanians retake Korytsá (Korçë)

[edit]In March 1920, French troops commenced the evacuation of the Republic of Korça.[58] The Greek army promptly endeavored to assume control in Epirus, thereby precluding the Albanians from establishing dominance in the region. However, the Greek plan was revealed to the Albanians by French Major Reynard Lespinasse. In response, the provisional government deployed 7,000 armed troops to the region to prevent the Greek forces from crossing the border. The two forces engaged in combat with one another, and the Greek plan to seize the city without a fight was unsuccessful. It is rumored that the Muslim population, fearful of the imminent entry of Greek troops into the city, is threatening to massacre the Christian population. To avert a bloodbath, the Greeks concurred with the French and British governments and determined that it would be prudent to refrain from occupying the city subsequent to the French departure. A provisional protocol is signed between the two forces in the village of Kapshticë. Athens accepts the status quo and acknowledges that the fate of Northern Epirus will be decided by the Peace Conference. Furthermore, it receives permission to militarily occupy 26 Hellenophone villages located southeast of Korytsá. In exchange, the Albanians occupy the rest of the district but promise to protect the Greek minority, its schools, and its freedom of expression.[59]

Italy's shift and the decision of the Conference of Ambassadors

[edit]On 17 May 1920, the U.S. Senate acknowledged Greece's territorial rights over Northern Epirus as stipulated in the Tittoni-Venizelos agreement.[55] For the Greek government, this represents a significant victory. Nevertheless, the situation remains unresolved. On 29 May, Albanian forces succeeded in driving the Italian Army out of Vlora. A few weeks later, Rome agreed to recognize Albanian independence and to evacuate the entire territory, retaining only the strategic island of Sazan. From that moment onward, the Italian government denounced the agreement made with Greece and supported Albanian interests at the Peace Conference.[60] In response to Roman hostility, the Conference referred the issue of Epirus back to the Conference of Ambassadors.[61][62]

On 9 November 1920, the Conference of Ambassadors, chaired by Paul Cambon, ultimately assigned the districts of Korytsá (Korçë) and Argyrókastro (Gjirokastër) to Albania. This decision was met with disappointment, particularly given the already-escalating conflict with Turkey. In response, Greece evacuated the 26 Hellenophone villages it had occupied and recognized Tirana's sovereignty over Northern Epirus.[63][64][65]

Limited recognition of the Greek minority

[edit]On 2 October 1921, the Albanian government, under the leadership of Ilias Bey Vrioni, formally endorsed the League of Nations Treaty on the Protection of National Minorities.[66]

Nevertheless, upon the reunification of Northern Epirus with Albania, the country's recognition of the rights of the Greek minority is confined to a narrow scope. This encompasses specific regions within the districts of Gjirokastër (Argyrókastro) and Sarandë (Aghioi Saranta), along with three villages situated in the vicinity of Himarë (Himara). In contrast with the Protocol of Corfu, which designated Northern Epirus as an autonomous region, the government's recognition of the Greek Epirote minority has not resulted in any form of local autonomy. Indeed, Greek schools in the region were even closed by the authorities until 1935.[67]

Historiography and legacy of the autonomist movement

[edit]According to sources from Albania, Italy, and the Austro-Hungarian Empire, the Epirote autonomist movement was a creation of the Greek state, supported by a minority of the region's inhabitants. These sources indicate that the movement caused instability and chaos throughout Albania.[68] In Albanian historiography, the Protocol of Corfu is frequently overlooked.[69] However, when it is referenced, it is often portrayed as an attempt to divide the Albanian state and as evidence that the major European powers did not recognize Albanian national integrity.[70]

Following the ratification of the Protocol of Corfu in 1914, the terms "Northern Epirus," which was the official designation of the autonomous government, and consequently "Northern Epirotes," were accorded official status. However, following the region's formal transfer to Albania in 1921, these terms became associated with Greek irredentism and were effectively disavowed by the Albanian authorities.[71] Anyone using these expressions in Albania was subsequently regarded as an "enemy of the state."[72]

The question of Epirote's autonomy has remained a pivotal point of contention in Greek-Albanian diplomatic relations.[73] In the 1960s, Soviet Union General Secretary Nikita Khrushchev requested that Albanian Head of State Enver Hoxha grant autonomy to the Greek minority in the region. This initiative, however, ultimately proved unsuccessful.[74][75] In 1991, following the collapse of the Albanian communist regime, the leader of the Omonoia organization, representing the Greek minority in the country, petitioned for autonomy for Northern Epirus, asserting that the rights afforded to the Hellenic community by the Albanian constitution were exceedingly tenuous. However, the proposal was once again rejected, prompting some Epirotes to embrace radical ideologies and demand that their region be annexed to Greece.[76]

Two years later, in 1993, the leader of Omonoia publicly elucidated the objective of the Greek minority, which was to achieve the establishment of an autonomous region within the Albanian Republic based on the Protocol of Corfu. As a result, he was promptly apprehended by the Tirana police.[73] In 1997, some Albanian analysts, such as Zef Preci of the Albanian Center for Economic Research, maintained the view that the risk of Northern Epirus seceding remained a tangible possibility.[77]

See also

[edit]- Epirus, Northern Epirus and Epirus (region)

- Autonomous Republic of Northern Epirus

- Autonomous Province of Korçë

- Greeks in Albania

- History of Albania

- Treaty of Florence

- Protocol of Corfu

- Wilhelm, Prince of Albania

- Eleftherios Venizelos

- Arvanites

- Chameria

Notes

[edit]- ^ a b In Greek, the word "autonomous" can mean both "independent" and "autonomous."

- ^ In this regard, the Orthodox Christians of Southern Albania strongly resemble the Arvanites of Greece, who also speak a dialect of Albanian close to Tosk but feel entirely Greek.

- ^ In The Balkan Wars: 1912–1913, Jacob G. Schurman notes: "During the first [Balkan] war the Greeks had occupied Epirus or southern Albania as far north as a line drawn from a point a little above Khimara on the coast due east toward Lake Presba, so that the cities of Tepeleni and Koritza were included in the Greek area."

- ^ The note from the Great Powers to Greece concerns the decision of European states to irrevocably cede to the Kingdom of Greece all the Aegean islands already occupied by it (except for Imbros, Tenedos, and Kastelorizo) on the day Greek troops evacuate the Northern Epirus regions granted to Albania by the Protocol of Florence.

- ^ The Albanian Church was then in formation, only declaring its autocephaly in 1922.

- ^ The Koundouriotis family is from Hydra, and the Danglis are of Souliote descent.

- ^ In Paris, Essad Pasha Toptani continued to present himself as the only legitimate leader of Albania, which contributed to weakening the provisional government of Turhan Pasha Përmeti and its representatives.

References

[edit]- ^ Stoppel, Wolfgang (2001). Minderheitenschutz im östlichen Europa, Albanien [Protection of minorities in Eastern Europe, Albania] (in German). University of Cologne. p. 11.

- ^ Ruches 1965, pp. 1–2

- ^ Newman, Bernard (2007). Balkan Background. Read Books. pp. 262–263. ISBN 9781406753745.

- ^ Jelavich, Barbara (1983). History of the Balkans : Twentieth Century. Cambridge University Press. p. 87.

- ^ Clayer, Nathalie (2005). "Le meurtre du prêtre, Acte fondateur de la mobilisation nationaliste albanaise à l'aube de la révolution Jeune Turque" [The murder of the priest, founding act of Albanian nationalist mobilization at the dawn of the Young Turk revolution]. Balkanologie (in French). IX (1–2): 6 & 23. Archived from the original on 5 June 2024.

- ^ a b Winnifrith 2002, p. 130

- ^ Hellenic Army General Staff (1998). An Index of events in the military history of the Greek nation. Athens. p. 98.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Hellenic Army General Staff 1998, p. 96

- ^ a b Miller, William (1966). The Ottoman Empire and Its Successors, 1801–1927. Routledge. p. 518.

- ^ Driault & Lhéritier 1926, pp. 83–84, Volume V

- ^ Chase, George H (2007). Greece of Tomorrow. Gardiner Press. pp. 37–38.

- ^ Pierpont Stickney 1926, p. 38

- ^ Kitromilídis, Paschális (2008). Eleftherios Venizelos : The Trials of Statesmanship. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press. pp. 150–151.

- ^ a b c Kondis 1976, p. 124

- ^ Driault & Lhéritier 1926, p. 155, Volume V

- ^ Pierpont Stickney 1926, p. 42

- ^ Boeckh 1996, p. 114

- ^ Ruches, Pyrrhus (1967). Albanian historical folksongs, 1716–1943: a survey of oral epic poetry from southern Albania, with original texts. Argonaut. p. 106.

- ^ Ruches 1965, p. 83

- ^ a b c d e f g Miller 1966, p. 519

- ^ Boeckh 1996, p. 115

- ^ a b c Heuberger, Suppan & Vyslonzil 1996, pp. 68–69

- ^ a b c d Ruches 1965, pp. 88–89

- ^ a b c Kondis 1976, p. 127

- ^ Pierpont Stickney 1926, p. 43

- ^ Ruches 1965, pp. 84–85

- ^ Sakellariou, M. V (1997). Epirus, 4000 years of Greek history and civilization. Ekdotike Athenon. p. 380. ISBN 978-960-213-371-2.

- ^ a b Ruches 1965, p. 91

- ^ Miller 1966, p. 520

- ^ Pierpont Stickney 1926, p. 50

- ^ Kondis 1976, pp. 132–133

- ^ Ruches 1965, p. 94

- ^ Balkan studies. Vol. 11. Institute for Balkan Studies, Society for Macedonian Studies. 1970. pp. 74–75.

- ^ Pearson 2004, pp. 75–77 & 82–83

- ^ Nicola 2007, p. 117

- ^ Pearson 2004, p. 83

- ^ Driault & Lhéritier 1926, p. 185, Volume V

- ^ Vaucher, Robert (7 April 1917). "La République Albanaise de Koritza" [The Albanian Republic of Koritza]. L'Illustration (in French). No. 3866.

- ^ a b Pierpont Stickney 1926, pp. 57–63

- ^ Pantelis, Antonis; Koutsoubinas, Stephanos; Gerapetritis, George (2010). "Greece". Elections in Europe : A Data Handbook. Baden-Baden: Nomos. p. 856. ISBN 9783832956097.

- ^ Pearson 2004, pp. 101–102

- ^ Winnifrith 2002, p. 132

- ^ Pearson 2004, p. 101

- ^ Popescu 2004a, pp. 79–82

- ^ Popescu 2004a, pp. 81 & 83

- ^ Popescu 2004a, p. 103

- ^ Driault & Lhéritier 1926, pp. 300 & 315–318, Volume V

- ^ Pearson 2004, pp. 120–134

- ^ Popescu 2004a, p. 82

- ^ a b Popescu 2004a, pp. 137–138

- ^ Augris, Étienne (2000). "Korçë dans la Grande Guerre, Le sud-est albanais sous administration française (1916–1918)" [Korçë in the Great War, Southeastern Albania under French administration (1916–1918)]. Balkanologie (in French). IV (2): 27–37. Archived from the original on 21 July 2024.

- ^ Pearson 2004, p. 130

- ^ Driault & Lhéritier 1926, pp. 336–338, Volume V

- ^ Driault & Lhéritier 1926, pp. 346–351, Volume V

- ^ a b An index of events in the military history of the Greek nation. Athens: Army History Directorate. 1998. p. 105.

- ^ Driault & Lhéritier 1926, pp. 351–352, Volume V

- ^ a b Pearson 2004, pp. 138–139

- ^ Popescu 2004a, p. 85

- ^ Pearson 2004, pp. 144–145

- ^ Pearson 2004, pp. 145–152

- ^ An index of events in the military history of the Greek nation. Athens: Army History Directorate. 1998. p. 106.

- ^ Driault & Lhéritier 1926, pp. 380–386, Volume V

- ^ Pearson 2004, pp. 175–176

- ^ Driault & Lhéritier 1926, p. 380, Volume V

- ^ Kitromilides 2008, pp. 162–163

- ^ League of Nations Treaty Series. Vol. 9. pp. 174–179. Archived from the original on 7 May 2023.

- ^ Kondis, Basil; Manda, Eleftheria (1994). The Greek Minority in Albania – A documentary record (1921–1993) (in 20). Thessaloniki: Institute of Balkan Studies.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - ^ Ruches 1965, p. 87

- ^ Gregorič 2008, pp. 144–145

- ^ Vickers, Miranda; Pettifer, James (1997). Albania: From Anarchy to a Balkan Identity. C. Hurst & Co. Publishers. p. 2.

- ^ King, Russell; Mai, Nicola; Schwandner-Sievers, Stephanie (2005). The New Albanian Migration. Sussex Academic Press. p. 66.

- ^ Hoxha, Enver (1985). Two friendly peoples: excerpts from the political diary and other documents on Albanian-Greek relations, 1941–1984. "8 Nëntori" Pub. House.

- ^ a b Heuberger, Suppan & Vyslonzil 1996, p. 73

- ^ Vickers & Pettifer 1997, pp. 188–189

- ^ Sakellariou 1997, p. 404

- ^ Lastaria-Cornhiel, Sussana; Wheeler, Rachel (1998). "Series, Gender Ethnicity and Landed Property in Albania" (PDF). Working Paper (18). Albania: Land Tenure Center, University of Wisconsin: 38. Archived from the original (PDF) on 24 March 2022.

- ^ Minorities at Risk Project (2004). "Chronology for Greeks in Albania". United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees website. Retrieved 9 August 2010.

Bibliography

[edit]History of Northern Epirus and the Epirote question

[edit]- Gregorič, Nataša (2008). Contested Spaces and Negotiated Identities in Dhërmi/Drimades of Himarë/Himara Area, Southern Albania (PDF). Nova Gorica: University of Nova Gorica Graduate School. Archived from the original (PDF) on 10 June 2011.

- Popescu, Stefan (2004a). "Les Français et la république de Kortcha (1916–1920)" [The French and the Kortcha Republic (1916–1920)]. Guerres Mondiales et Conflits Contemporains (in French). 1 (213): 77–87. doi:10.3917/gmcc.213.0077. Archived from the original on 12 April 2023.

- Ruches, Pyrrhus J (1965). Albania's captives. Chicago: Argonaut.

- Pierpont Stickney, Edith (1926). Southern Albania or Northern Epirus in European International Affairs, 1912–1923. Chicago: Stanford University Press.

- Winnifrith, Tom (2002). Badlands-borderlands : a history of Northern Epirus/Southern Albania. London: Duckworth. ISBN 978-0-715-63201-7. OCLC 796056855.

History of the Balkans, Albania and Greece

[edit]- An index of events in the military history of the Greek nation. Athens: Army History Directorate. 1998. ISBN 978-9-607-89727-5. OCLC 475469625.

- Boeckh, Katrin (1996). Von den Balkankriegen zum Ersten Weltkrieg: Kleinstaatenpolitik und ethnische Selbstbestimmung auf dem Balkan [From the Balkan Wars to the First World War: The policy on small states and ethnic self-determination in the Balkans] (in German). Oldenbourg, Wissenschaftsverlag. ISBN 9783486561739.

- Chase, George H (2007). Greece of Tomorrow. Gardiner Press. ISBN 9781406707588.

- Driault, Édouard; Lhéritier, Michel (1926). Histoire diplomatique de la Grèce de 1821 à nos jours [Diplomatic history of Greece from 1821 to the present day] (in French). Vol. III, IV and V. Paris: PUF. Archived from the original on 4 April 2022.

- Glenny, Misha (2000). The Balkans : Nationalism, War, and the Great Powers, 1804–1999. New York: Viking. ISBN 978-0-670-85338-0. OCLC 695555751.

- Nicola, Guy (2007). "The Albanian Question in British Policy and the Italian Intervention, August 1914 – April 1915". Diplomacy & Statecraft. 18 (1).

- Heuberger, Valeria; Suppan, Arnold; Vyslonzil, Elisabeth (1996). Brennpunkt Osteuropa : Minderheiten im Kreuzfeuer des Nationalismus [Focus on Eastern Europe: Minorities in the crossfire of nationalism] (in German). Vienna: Verlag für Geschichte und Politik R. Oldenbourg. ISBN 978-3-486-56182-1.

- Kondis, Basil (1976). Greece and Albania 1908-1914. Thessaloniki: Institute for Balkan Studies.

- William, Miller (1966). The Ottoman empire and its successors, 1801–1927. Abingdon, Oxon, Frank Cass. ISBN 978-0-714-61974-3. OCLC 7385551832.

- Pearson, Owen (2004). Albania and King Zog : independence, republic and monarchy 1908-1939. Albania in the twentieth century. London New York: Centre for Albanian Studies in association with IB Tauris Publishers. ISBN 978-1-845-11013-0. OCLC 433607033.

- Popescu, Stefan (2004). "L'Albanie dans la Politique Étrangère de la France, 1919-1940" [Albania in French foreign policy, 1919–1940]. Valahian Journal of Historical Studies (in French) (1/2004): 20–58.

- Schurman, Jacob Gould (1916). The Balkan Wars: 1912–1913.

Biography of a personality linked to the Epirote question

[edit]- Kitromilides, Paschalis (2008). Eleftherios Venizelos : The Trials of Statesmanship. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press. ISBN 9780748633647.