History of France's military nuclear program

The history of France's military nuclear program recounts the path that led France to develop a military nuclear program after World War II. The establishment of the French Nuclear Deterrence Force was based on a French nuclear testing program that began on February 13, 1960, and ended on January 27, 1996.

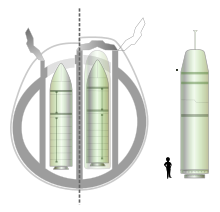

In 2012, the Strategic Oceanic Force comprises four nuclear-powered ballistic missile submarines equipped with strategic sea-to-surface ballistic missiles. The Strategic Air Force uses enhanced medium-range air-to-surface missiles with airborne warheads under Dassault Mirage 2000 aircraft at air base 125 Istres-Le Tubé. This missile is also used with Dassault Rafale aircraft at air base 113 Saint-Dizier-Robinson and on board the aircraft carrier Charles de Gaulle.

The scientific adventure of the atom (1895-1945)

[edit]The origins (1895-1903)

[edit]

International scientific research into the atom began with the discovery of X-rays by German physicist Wilhelm Röntgen on November 8, 1895, in Würzburg, following the observation of a strange, pale glow coming from a luminescent screen placed, by chance, on a table at a distance from a Crookes tube. He soon realized that this was a new form of radiation, produced when electrons collide with atoms on the positive electrode (the cathode) when an electric current is passed through a cathode ray tube.[1][2] In France, following Henri Poincaré's presentation of Röntgen's discovery of X-rays to the Frencg Academy of Sciences in early 1896, Henri Becquerel decided to investigate the relationship between the luminescence of certain materials and the emission of these mysterious X-rays.[3] Experimenting in 1896 to find the origin of this luminescence, he discovered by chance that uranium salts spontaneously emitted radiation, whether or not they had been exposed to light. At first, he dubbed them uranic rays.[4]

From 1896 onwards, Pierre and Marie Curie set out to find an explanation for the phenomenon discovered by Wilhelm Röntgen and for these uranic rays. They processed hundreds of kilos of uranium ore by crushing it and dissolving it in acid. In 1898, Marie Curie discovered that thorium had the same radiation properties as uranium. The two physicists went on to isolate a first element, named polonium in homage to Marie's homeland, and then a second, even more active element: radium. These discoveries earned them the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1903, along with Henri Becquerel.[4]

In 1903, Ernest Rutherford came up with an explanation for the presence of these new elements and the links between them. He hypothesized that the radioactive elements found around uranium and thorium were linked together, with the heavier element losing its substance through decay to give rise to another element, and so on.[4]

The internal structure of the atom (1903-1932)

[edit]In 1910, Rutherford provided the first representation of the atom's internal structure: a positively charged nucleus around which negative charges gravitate. But it was Niels Bohr who explained in 1913 that electrons do not collapse on the nucleus due to attraction and remain at a given level, using Max Planck's quantum theory.[5]

Irène, Marie Curie's daughter, and Frédéric Joliot-Curie observed that beryllium bombardment could give rise to the projection of protons, in addition to the emission of radioactivity. The Englishman James Chadwick provided a decisive explanation in 1932 when he discovered the existence of neutrons in the atom, uncharged particles alongside protons.[6]

The discovery of nuclear energy (1932-1939)

[edit]

It was the work of Irène and Frédéric Joliot Curie that really gave birth to nuclear physics. At the end of 1933, by bombarding aluminum foil with a polonium source, they demonstrated the production of radioactive phosphorus 30, an isotope of naturally occurring phosphorus 30. They deduced that it was possible to produce elements with the same properties as natural elements, but which were also radioactive. Right from the start, they saw all the possible applications, particularly in the medical field, with radioactive tracers. They were awarded the Nobel Prize for this discovery in 1935.[6]

The chain reaction

[edit]In 1934, Italy's Enrico Fermi observed that neutrons slowed down (by a journey through kerosene, for example) were much more efficient than ordinary neutrons. Future facilities would need to include "moderating" materials such as heavy water.[7]

Numerous European research laboratories bombarded nuclei to analyze their effects. In December 1938, two Germans exiled in Sweden, Lise Meitner and Otto Frisch, came up with a key explanation of nuclear energy, the phenomenon of nuclear fission.

In February 1939, Niels Bohr demonstrated that, of the two isotopes contained in natural uranium: 238U and 235U, only uranium 235 is "fissile". What's more, it is much rarer than uranium 238, accounting for just 0.72% of the uranium extracted from a mine.

Finally, in April 1939, four Frenchmen - Frédéric Joliot-Curie, Hans Halban, Lew Kowarski and Francis Perrin - published an article in the journal Nature, shortly before their American rivals, which was to prove fundamental for future events, demonstrating that fission of the uranium nucleus is accompanied by the emission of 3.5 neutrons (the exact figure would be 2.4), which can in turn fragment other nuclei and so on, in a "chain reaction".[7]

The three French patents

[edit]

In early May 1939, the four Frenchmen filed three patents: the first two concerned the production of energy from uranium, and the third, a secret one, the improvement of explosive charges.[8][9] All three were employed by the Collège de France as part of a team headed by Frédéric Joliot. Joliot, convinced of the future importance of civilian and military applications of atomic energy, met Raoul Dautry, Minister of Armaments, in the early autumn of 1939. He gave his full support, firstly for explosives development and secondly for energy production.[9]

In July 1939, experiments on the release of energy by chain reaction began at the Collège de France laboratory and continued in Ivry-sur-Seine at the Laboratoire de Synthèse Atomique (founded under the Popular Front under the aegis of the Caisse Nationale pour la Recherche Scientifique, which had acquired the Ampère laboratories of the Compagnie Générale Électro-Céramique).[10][11] To secure his patents, Joliot wove an industrial network around him, notably through an agreement between the CNRS and the Union Minière du Haut Katanga, owner of the uranium in the Belgian Congo.[12]

In autumn 1939, the Joliot team realized that France would not have the means to enrich natural uranium to its fissile isotope (235U), and turned to the use of heavy water.[13] In February 1940, at the request of the Collège de France, Raoul Dautry sent Jacques Allier on a secret mission to Norway to acquire the entire 200-litre stock of heavy water held by Norsk Hydro (a company with partly French capital), a stock that Germany also coveted.[9]

Suspension of research in France (1940-1945)

[edit]

Germany's invasion of France in May 1940 forced work to stop. In early June, the laboratory was hastily moved from Paris to Clermont-Ferrand, but the war was already lost.[14] On June 18, 1940, as General de Gaulle launched his famous appeal on the London radio, Hans Halban and Lew Kowarski embarked at Bordeaux for the United Kingdom, taking the heavy water. The uranium was hidden in Morocco and France.[15] Joliot did not leave, remaining in France to care for his ailing wife,[16] returning to his post at the Collège de France but refusing to collaborate. He officially joined the Resistance in 1943.[17]

The exiled members of the Collège de France delivered French secrets to the Allies, but were excluded from the American nuclear program for economic (the three patents) and political (distrust of de Gaulle and Joliot) reasons.[18] Isolated at the Cavendish laboratory in Cambridge, then at the Montreal laboratory from the end of 1942, they contributed to the work carried out by an Anglo-Canadian team.[9] This work was to be decisive for the resumption of French research in this field.

Under the direction of Louis Rapkine, a scientific office for the Free French Delegation was set up in New York shortly after the United States entered the war in December 1941. It was through this office that French scientists in exile, such as Pierre Auger, Jules Guéron and Bertrand Goldschmidt, were integrated - not into the American teams themselves, as they refused to take the nationality - but into the Anglo-Canadian project headed by Halban.[19]

France gets left out of the picture

[edit]On August 19, 1943, the United States and the United Kingdom signed the Quebec Agreement merging their respective nuclear programs (Tube Alloys and Manhattan) and stipulating non-disclosure of their work. They knew that France and the USSR would soon catch up, but did not want to make it easy for them. In this regard, Winston Churchill declared: "In all circumstances, our policy must be to keep the matter, as far as we can control it, in American and British hands, and to let the French and Russians do what they can".[20] With this in mind, on March 23, 1944, the Americans and British signed an agreement with the Belgian government in exile in London, reserving Congolese uranium production for themselves, thus rendering null and void the private agreement of 1939 with the CNRS.[21]

On July 11, 1944, in a back room of the Ottawa consulate, Guéron, Auger and Goldschmidt informed General De Gaulle of the American nuclear program and the prospects opened up by fission.[22] This information confirmed what the General had already learned in London.[23][24] As soon as Paris was liberated in August 1944, the first group of French scientists, including Auger, returned from Montreal against American advice. The British let this happen because they had to deal with De Gaulle, who might demand the sharing of atomic secrets or draw closer to the Russians.[25] They chose to manipulate Joliot, favored by the General, who exaggerated the difficulties involved in making the bomb, while assuring him that they would cooperate.[26] In April 1945, the towns to which the German atom scientists had retreated fell to the 1st French Army, but the men of Alsos Mission raided the laboratories, including the Haigerloch atomic reactor, captured the German scientists and left nothing behind but a few technicians.[27]

Shunned by the Anglo-Americans, deprived of uranium sources and with meagre war prizes, the French nuclear program was going to have to operate independently,[28] all the more so as the Minister of Armaments, Charles Tillon, was a member of the French Communist Party.[29]

The beginnings of a military nuclear program (1945-1958)

[edit]France's position at the end of World War II (1945-1949)

[edit]"As for the atomic bomb, we have time. I am not convinced that we will have to use atomic bombs in the very near future in this world."

— Charles de Gaulle, October 1945.

As early as May 1945, Raoul Dautry (then Minister for Reconstruction and Town Planning in the Provisional Government) informed General de Gaulle (then President of the Provisional Government) that nuclear power would benefit both reconstruction and national defense.[28] The progress made by American research in this field was revealed to the general public by the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki on August 6 and 9, 1945. On August 31, de Gaulle commissioned Raoul Dautry and Frédéric Joliot to propose an organization for the French nuclear industry capable of mobilizing energies to build the bomb.[30]

On October 18, 1945, the French Alternative Energies and Atomic Energy Commission (Commissariat à l'énergie atomique - CEA) was created by Ordinance 45–2563. Reporting directly to the President of the French Council, its mission was to pursue scientific and technical research into the use of nuclear energy in various fields of industry, science and defense.[31][32] The first two people to share responsibility for running the organization were Joliot, as High Commissioner for Scientific and Technical Affairs, and Dautry, as General Administrator.[33]

However, the importance attributed to military nuclear power in 1945 should not be overestimated, as the country's reconstruction was primordial. "I am Minister of Reconstruction, not of Destruction", as Dautry would say.[34] In this context, and under the influence of Joliot (a pacifist and member of the Communist Party), opposition to the military use of the atom spread within the CEA. In the euphoria of the Allied victory, Joliot declared "I'll make you a bomb, General, your bomb",[35] but he soon changed his mind and, as High Commissioner of the CEA, wanted France to adopt a position opposed to military nuclear power (a worldwide ban on the manufacture of atomic weapons). This political position was asserted on June 25, 1946, by Ambassador Alexandre Parodi before the first UN[28] atomic energy commission. It also became the official position of the Fourth Republic, enabling it to conceal its weakness and secrets.[36]

On May 17, 1946, the Direction des Etudes et Fabrications d'Armement set up the Laboratoire de Recherches Balistiques et Aérodynamiques (LRBA) in Vernon, on a former shell manufacturing site initiated by Edgar Brandt and nationalized in 1936.

Zoé, the first French atomic reactor (1948)

[edit]

Fort de Châtillon, in the commune of Fontenay-aux-Roses, was assigned to the CEA on March 8, 1946, and it was here that France's first atomic reactor, Zoé, went into operation ("diverge") on December 15, 1948.[33] This fuel cell uses natural uranium oxide moderated with heavy water. It produced almost no energy, just a few kilowatts, but it enabled the study of nuclear reactions and the production of radio-elements for research and industry.[37]

Uranium ore from Africa is refined in an enclave of the Poudrerie du Bouchet, near Ballancourt-sur-Essonne. On November 20, 1949, chemist Bertrand Goldschmidt and his team isolated the first four milligrams of French plutonium. This was a significant event, as the irradiated fuel removed from the Zoé reactor could now be processed and the plutonium extracted, an essential step in the construction of the first atomic bomb.[38]

In 1949, construction of the Saclay center began. In 1952, a particle accelerator was commissioned and the second heavy water reactor (EL2) diverged. It was designed for physics and metallurgy experiments, as well as for the production of artificial radio-elements.[38][39]

The end of the pacifist position (1950-1954)

[edit]The unfolding of the Cold War in general, and the explosion of the first Soviet nuclear bomb in 1949 in particular, led France to abandon the CEA's pacifist stance, as asserted by Frédéric Joliot. After making public statements in favor of the Soviet Union, Joliot was forced to resign from the CEA on April 28, 1950, under the pretext that he had launched the Stockholm Appeal.[40] The French government took advantage of the situation to point out that the Commissariat was also responsible for national defense.[28]

However, the question of France's atomic weapons was still not officially raised. The first five-year nuclear energy plan, drawn up by Félix Gaillard (then Secretary of State to the President of the Council in the Pinay government) and passed by the National Assembly in June 1952, aimed to develop nuclear power over the long term. In terms of power generation, the main aim of the plan was to find a solution to France's energy deficit. Félix Gaillard was later appointed Chairman of the Atomic Energy Coordination Commission on March 18, 1955.[41] The Communist Party proposed an amendment to prohibit France from manufacturing atomic weapons, but the deputies overwhelmingly rejected it. Even some opponents of the military use of nuclear energy (such as the socialist Jules Moch) voted against the amendment, arguing that France should not unilaterally prohibit itself from doing so.[42]

Building the Marcoule nuclear power plant

[edit]As the CEA did not have the technical and financial resources to enrich natural uranium to its fissile isotope (235-U), it could not develop pressurized water reactors (PWRs) or manufacture nuclear weapons using it. As a result, like the UK, France turned to graphite-based atomic reactor technology, which gave rise to the natural uranium graphite gas reactor (UNGG).[28] This type of reactor used natural uranium as fuel, graphite as neutron moderator and carbon dioxide as coolant for turbines and core cooling. In addition to generating electricity,[43] these reactors produced plutonium in large enough quantities, at a cost three times lower than that of highly enriched uranium, to enable a future military program or a civil fast-breeder reactor program.[44][45]

The Gaillard plan called for the construction of two reactors, with work starting in 1955 and a third to follow later. The first reactor (G1) diverged on January 7, 1956[46] at the Marcoule nuclear site. Air-cooled, it was still a prototype with limited power (40 MWt), producing less electrical energy than it consumed. The next two units, G2 in 1958 and G3 in 1959, were more powerful (150 MWt) and were to become the standard-bearers of the UNGG process.[45]

To meet new fuel requirements, new uranium mines were opened in Vendée at the Fleuriais site, in Mortagne-sur-Sèvre[47] and in Forez,[48] in addition to those already in operation in Limousin.[49][50] By the end of 1956, ore production had reached 175 tonnes of contained uranium.[45]

Multiple factors leading to the bomb

[edit]"Ah, if I'd had the bomb, I wouldn't have had to swallow so much...".

— Remarks by Pierre Mendès France, Negotiating peace in Indochina, reported by Yves Rocard

Although the 1952 Five-Year Plan paved the way for the French nuclear bomb, the decision to build it was not taken at that time. In fact, France did not decide to use nuclear energy for military purposes until 1954, on the basis of:[42]

- the defeat at Diên Biên Phu, faced with the encirclement of French troops at Diên Biên Phu in March 1954, the Comité de Défense restreint asked the United States to use atomic weapons, a request the White House ignored. It thus became clear that the military alliance with the United States could not fully guarantee French interests;

- the treaty concerning the European Defense Community (EDC), which prohibited member states from undertaking an independent military nuclear program. This treaty, although rejected by the French parliament in August 1954 after four years of debate, highlighted the need for a decision;

- a change in NATO's strategy, in favor of massive and early retaliation through the use of atomic weapons. Against this backdrop, in September 1954, the Chiefs of Staff of the French armed forces decided in favor of national atomic weapons integrated into NATO.

At the same time, from March 1954 onwards, General Paul Ély emphasized to René Pleven (Minister of Defense) the importance of nuclear weapons for a nation's global power. He based his argument on the opinions of the Chiefs of Staff, the capabilities of the CEA and the plutonium resources developed under the 1952 five-year plan.[51] General Ely recommended that:[51]

- military personnel to be associated with the CEA;

- the CEA's budget be increased and placed under the control of the Ministry of Defense;

- to create a special joint military committee.

Added to this was the explosion of the first British nuclear bomb on October 3, 1952, which challenged France's leadership in Europe.

From secretive beginnings to the test decision (1954-1958)

[edit]In fact, it was the government of Pierre Mendès France that came out in favor of developing a French military nuclear program after the French National Assembly rejected the EDC on August 30, 1954. Mendès-France, then President of the council, had political advantages in launching the first stage of work leading to such a program, knowing that the final decision to build an atomic bomb would be taken later.[51] On October 26 of the same year, he signed a secret decree creating the Commission Supérieure des Applications Militaires de l'Énergie Atomique (CSMEA). On November 4, he signed another secret decree, creating the Comité des Explosifs Nucléaires (CNE).[51] Unlike the CNE, the CSMEA never had to meet. The CNE, like the CEA, depended closely on the President of the council.

On December 24, 1954, the CNE submitted a draft military atomic program to Pierre Mendès-France:[51]

- the construction of two G2 nuclear reactors to produce 70 to 80 kg/year of plutonium;

- the creation of the Bureau d'Études Générales (BEG) to set up and manage the scientific and technical teams;

- the creation of a test center to develop the measuring devices to be used during actual tests;

- the creation of a test center in the Sahara, the Centre d'expérimentations militaires des oasis;

- the creation of a permanent test detection network;

- the study of isotope separation.

On December 26, 1954, Pierre Mendès-France convened a meeting of experts. The conclusions, long debated, appear to have been:[51]

- the secret launch of a nuclear weapons program;

- the launch of a nuclear submarine program;

- a draft decision submitted to the Council of Ministers.

This last decision was never submitted because of the fall of the Mendès-France cabinet a few weeks later.

The role of Pierre Mendès France

[edit]In the 1970s, Pierre Mendès France denied his role in the launch of the nuclear atomic program: it was only a step towards the atomic bomb and, had he continued in his role as President of the council, he would have been free to decide in the following years for or against the actual production of the atomic bomb.[51] According to Pierre Mendès-France, the December 1954 decision was purely political: France intended to put pressure on the USSR and the US to abandon the tests, while keeping open the possibility for France to implement its own military nuclear program should the tests continue.

Pierre Mendès-France did, however, pave the way for France's military nuclear program at the end of 1954, even if it was primarily a diplomatic weapon for future negotiations. His statements in the 1970s also appear to have been linked to domestic political ends, as his electorate and activists were pacifists.[51]

The CEA organized for the bomb

[edit]The BEG, forerunner of the Direction des applications militaires (DAM), was created within the CEA on December 28, 1954.[52] On March 1, 1955, General Albert Buchalet took over as director and received oral orders to build the bomb. On May 20, a secret protocol was signed between the French armed forces and the CEA, which was recognized as the prime contractor for atomic weapons.[53][54] The Minister for Atomic Energy, Gaston Palewski, increased the CEA's five-year budget from 40 to 100 billion Francs, setting the French military nuclear program on a long-term course.[55]

On June 3, 1955, the CEA integrates specialists from the Société nationale des poudres et des explosifs into a center dedicated to detonation at the Vaujours fort.[56] Since the end of 1954, the CEA had had a 30-hectare site at Bruyères-le-Châtel (near Arpajon), financed by the Service de Documentation Extérieure et de Contre-Espionnage (SDECE). In July 1955, it became home to the BEG's new nuclear studies center, with the first scientific team arriving in July 1956.[51] From 1957, annexes to these two centers were built at Valduc, in Burgundy, and Moronvilliers, in Champagne, to conduct neutron and criticality studies on plutonium far from Paris.[54][57]

With the program under the direction of the CEA, and despite their resistance, the military had no choice but to recognize the CEA's leadership.[51] As a result, it was not until 1958, under pressure from General de Gaulle, that engineers from the atomic section of the Direction des Études et Fabrications d'Armement (DEFA) joined the BEG. It was they who came up with the neutron ignition solution used in the atomic test of February 1960.[51]

"Studies on nuclear explosives have been initiated and will be continued."

— Guy Mollet, National Assembly, July 11, 1956.

During the Suez Canal crisis, the USSR was the first nation to use atomic blackmail in a diplomatic context, with Russian Marshal Nikolai Bulganin threatening Paris and London with nuclear-tipped intercontinental rockets if the two countries did not put an end to their expedition. So, at the end of 1956, Guy Mollet decided to speed up the French nuclear program and develop it outside the United States.[58]

An important step was taken with Félix Gaillard's ministerial decision of April 11, 1958, to prepare a first series of experimental nuclear explosions in the Algerian Sahara during the first quarter of 1960.[59][60] This decision was confirmed by General de Gaulle on his return to government.[51]

A protocol signed between the Ministries of Finance and of Armed Forces on November 30, 1956, provided for the construction of a uranium enrichment plant by the CEA. Programming for this plant was made official in July 1957, with the parliamentary vote on the second five-year atomic energy plan. Work on the Pierrelatte military plant began in 1960, and the first ingot of low-enriched uranium was produced in January 1964.[51]

Formalization of the military nuclear program (1958)

[edit]It was not until 1958 that General de Gaulle made France's military nuclear program official. Prior to 1958, the Presidents of the French Council (Pierre Mendès France, Edgar Faure and Guy Mollet) adopted a double discourse, which should have not minimized the decisions taken in the intervening years. In 1955, the French nuclear program was allocated a specific budget, giving it a long-term perspective.[51] On July 5, 1958, de Gaulle warned U.S. Secretary of State John Foster Dulles: "Everything is organized on the basis of atomic force. You have this force [...] We are far behind you [...] One thing is certain: we will have atomic weapons".[61]

From the Fourth to the Fifth Republic

[edit]Although the success of France's military nuclear program was achieved under the Fifth Republic, it was in fact under the Fourth Republic that it began, in secret. Under the Fourth Republic, French politicians saw French nuclear weapons as part of NATO. Under the Fifth Republic, nuclear weapons were seen as a guarantee of national independence from NATO. However, the decision to withdraw from the organization's integrated military bodies, notified to US President Johnson in 1965, was intended to strengthen France's position, rather than sever ties with its allies or break up the alliance.[51] For de Gaulle: "American nuclear weapons remain the essential guarantee of world peace. [...] But the fact remains that American nuclear power does not necessarily respond immediately to all eventualities concerning Europe and France".[62]

The nuclear testing program (1960-1996)

[edit]

The first trials in Algeria (1960-1966)

[edit]Aerial testings at Reggane

[edit]"Never have I felt more than at this moment that our country had truly overcome the defeat of 1940 and that it had the future to itself."

— Félix Gaillard, Gerboise bleue, February 13, 1960.

France's first nuclear test, Gerboise bleue, was carried out on February 13, 1960, on the Reggane firing range, more precisely some 50 kilometers to the southwest at Hamoudia, in the center of the Algerian Sahara, 600 kilometers south of Bechar.[63] Two further tests (Gerboise blanche and Gerboise rouge) were carried out the same year.

The CEA's 1960 annual report showed the existence of a contaminated zone some 150 km long.

In the immediate aftermath of the generals' putsch (April 23, 1961) (also known as the "Algiers putsch"), the French government ordered the detonation of the Gerboise verte on April 25, 1961, to prevent the nuclear device from falling into the hands of the putschist generals.[64]

Gallery testings in the Hoggar

[edit]France abandoned atmospheric testing in favor of less polluting underground testing. The chosen site, In Ecker (Algerian Sahara), lay south of Reggane and around 150 km north of Tamanrasset. Firing was carried out in galleries dug horizontally into the Tan Afella granite massif of the Hoggar. These galleries were spiral-shaped to break the blast and were closed by a concrete slab. They were designed to ensure effective containment of radioactivity.

On November 7, 1961, France carried out its first underground nuclear test. But on May 1, 1962, during the second underground test, a radioactive cloud escaped from the firing gallery. This was the Béryl accident (the code name of the test).

Between November 1961 and February 1966, thirteen tunnel tests were carried out, four of which (Beryl, Amethyst, Ruby and Jade) were not completely contained or confined. However, the Évian Accords stipulated that France should abandon its experiments in the Sahara, and the French government began looking for another site.

The Pacific Experimental Center (1966-1996)

[edit]

Aerial testings

[edit]On July 2, 1966, the first aerial nuclear test took place on Moruroa atoll in French Polynesia.

Two years later, on August 24, 1968, the first H-bomb test took place on the Fangataufa atoll, codenamed Operation Canopus.

A total of 46 aerial nuclear tests were carried out in Polynesia, using a variety of techniques:

- barge testing;

- tethered balloon tests;

- aircraft releases, which reproduce real-life conditions fairly closely;

- safety tests to ensure that bombs do not explode until they are primed. In principle, these tests do not cause an explosion.

On July 19, 1974, the radioactive cloud resulting from the "Centaur" test actually hit Tahiti. Heavy rainfall, combined with the effects of relief, led to ground deposits, heterogeneous in terms of surface activity: at Hitiaa O Te Ra on the Taravao plateau, and south of Teahupo'o.

The return to underground testing

[edit]From 1975 to 1996, France carried out 146 underground tests in Polynesia, in the subsoils and lagoons of the Moruroa and Fangataufa atolls.

On August 6, 1985, the Treaty of Rarotonga (Cook Islands) was signed, declaring the South Pacific a nuclear-free zone. France was not involved. On July 15, 1991, the last French test in the Pacific was launched before the one-year moratorium decided by President François Mitterrand on April 8, 1992, and subsequently renewed.

On June 13, 1995, President Jacques Chirac broke the moratorium and ordered a final nuclear test campaign in the Pacific. The aim of this final campaign was to complete the scientific and technical data required for a definitive transition to simulation.

The six nuclear tests ended with a final test at Fangataufa on January 27, 1996.[65]

The development of a dissuasive force (1960-2020)

[edit]

General de Gaulle defined the means of an autonomous French deterrent on November 3, 1959, during a conference at the École Militaire. In his view, the country's military independence was based on "a strike force that could be deployed at any time and anywhere. It goes without saying that the basis of this force will be atomic weapons".[66] The doctrine governing the use of these resources was not yet clearly defined.[67]

In 1959, the Société d'étude et de réalisation d'engins balistiques (SEREB) was created as the government's agent and prime contractor for the future weapon systems of the Force nucléaire stratégique (FNS). A year later, SEREB collaborated with Nord-Aviation and Sud-Aviation to establish the "Études balistiques de base" (EBB) programs, known as the "Precious Stones". These programs were designed to acquire the technologies needed for the FNS. It was also in 1959 that the first Mirage IV bomber, built by Dassault, was presented in flight to General de Gaulle at the Paris Air Show, just three years after the project was signed.

France's first nuclear test, in the Algerian Sahara, was followed in 1961 by the flight test of the Agate rocket, the first in the "Pierres précieuses" series, at the Centre interarmées d'essais d'engins spéciaux at Colomb-Béchar in French Algeria.

Weak-to-strong strategy

[edit]While these new weapons, under strictly French command, guaranteed strategic autonomy, they were not enough, since France, lacking the means to match the Soviet Union in terms of nuclear and conventional weaponry, still had to rely on American support to guarantee its security.[68] From this perspective, French nuclear weapons could have served as a "detonator" for American weapons in the event of conflict, forcing a reluctant American president to help his allies. Within the framework of an integrated Western Command, the United States would have been obliged to consult the French before making any decisions, thus affirming France's status as a great power as intended by de Gaulle.[69] As Jacques Chirac put it: "We don't want to leave anyone with a monopoly on this or that category of weapons".[70] But the cost of such an undertaking called for a doctrine of use compatible with national resources. The French doctrine of immediate and total nuclear retaliation, inspired by the doctrine of massive retaliation, was defined in 1963.[67] This three-point doctrine of "sufficiency" was opposed to the American doctrine of flexible response adopted by the Kennedy administration:

- as early as 1961, the future Strategic Air Forces (SAF) were asked to be capable of "inflicting on the USSR a significant reduction, i.e. around 50%, in its economic function";

- following on from this, priority was given to the "anti-cities" strategy, linked to the idea of "weak to strong" dissuasion, reputed to be "the most dissuasive and least costly for a middle power like France". This strategy refuses to limit destruction to opposing offensive means ("anti-forces" strategy), hypothetically leading to a nuclear war against metropolitan France, which the latter cannot survive;

- the FAS must be capable of inflicting damage in all circumstances, including retaliatory damage "in second gear", and does not require early warning systems such as AWACS or BMEWS, particularly as the major adversary (the Soviet Union) is clearly identified.[71]

Mirage IV (1964)

[edit]

1964 marked the beginning of France's permanent nuclear deterrent. On January 14, the Strategic Air Forces were created. In February, the first Mirage IV and the first C-135F tanker arrived in the forces. In October, the first alert by a Mirage IV, armed with the AN-11 bomb, and a C-135F tanker takes place at Mont-de-Marsan air base (Landes). The trio of nuclear weapon (AN-11), carrier aircraft (Mirage IV) and projection aircraft (tanker) was now operational.

In the spring of 1966, with nine Mirage IV squadrons, the 1st component of the dissuasion force was completed. By 1973, 60 Mirage IVs at nine bases were on alert.[72]

The nuclear triad (1971)

[edit]

In 1963, the French government opted to build two new strategic land and naval weapons systems to complement the Mirages IV:

- surface-to-surface missiles to be fired from a missile launch facility: the S2;

- MSBS sea-to-surface missiles to be fired from nuclear-powered submarines.

The first operational unit of nine S2 missiles at Base aérienne 200 Apt-Saint-Christol on the Plateau d'Albion went into service on August 2, 1971, the second on April 23, 1972.[73]

On December 1, 1971, the first nuclear-powered ballistic missile submarine (SNLE) enters service: Le Redoutable. It was followed by five others, commissioned between 1973 and 1985.

Tactical nuclear weapons (1972)

[edit]The deployment of French tactical nuclear weapons fills the gap left in the Army's equipment by the withdrawal of the American Honest John missiles in 1966, but pushes the national all-or-nothing strategy. Their precise role was not defined until the presidency of François Mitterrand. These tactical weapons were then called "pre-strategic", as they would have been used as a final warning to the enemy, in the event of an unstoppable invasion by conventional means, prior to strategic strikes.[74]

In October 1972, two Mirage IIIE squadrons of the 4th fighter wing of the Force aérienne tactique (FATac) were assigned the tactical nuclear mission with the arrival of the AN-52 bomb.[75] On October 1, 1974, two squadrons of SEPECAT Jaguars from the 7th Fighter Wing were officially declared tactical nuclear. They were joined in this mission by a third squadron on January 1, 1981. One squadron relinquished this role on July 31, 1989, followed by the last two on August 31, 1991.[76]

On May 1, 1974, the first of five Pluton missile regiments entered service with the French army.

On December 10, 1978, following an IPER, the aircraft carrier Clemenceau was nuclear-qualified, and a special room was built to accommodate four or five AN-52 nuclear weapons for use by the French Navy's Super-Étendard aircraft.[77] Between 1980 and 1981, it was the Foch's turn to be fitted out for this function, with operational service starting on June 15, 1981.[78][79]

France and NATO (1974 declaration)

[edit]The Ottawa Declaration of 1974, the terms of which have since been taken up almost word for word in all the major NATO texts, acknowledged the "indirect contribution of French deterrence to the security of the alliance, which lies.. in the fact that the existence of an autonomous deterrent complicates the calculation of a potential aggressor."[80]

The third world nuclear force (1980)

[edit]

In the 1980s, the Strike Force reached its peak with over 500 nuclear warheads, distributed as follows:

- 64 missiles, some of them (M4) mirved, carried by six SNLE based at Île-Longue, in the Brest harbor. More than 300 warheads for a destructive power of 44 megatons in November 1987,[81] making this vector the centerpiece of the French deterrent;

- 18 S3 missiles in silos at the 200 Apt-Saint-Christol air base on the Plateau d'Albion, with the first operational unit commissioned on June 1, 1980, and the second on December 31, 1982;

- 30 Pluton missiles in five Army artillery regiments, to be replaced by the Hadès missile;

- some sixty ASMP air-to-surface missiles and AN-22 bombs for use by the French Air Force's Mirage IV (34 in service in 1983)[82] and Dassault Jaguar aircraft, and the French Navy's Super-Étendard.

The Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists estimated a peak of 540 warheads in 1992, for a total of 1,260 weapons built since 1964.[83]

Arsenal reduction and modernization (since 1991)

[edit]The reduction of France's nuclear arsenal began in 1988, with the replacement of five Mirage III and Jaguar squadrons by three Mirage 2000N squadrons.[84]

On September 11, 1991, French President François Mitterrand announced the early withdrawal of the Pluton missiles, the last of which were deactivated on August 31, 1993. Its replacement, the Hadès, was authorized in 1991, but in reduced numbers.

Little is known about the cooperative ventures between France and the US of the 1980s and 1990s.[85][86]

In 1992 Mitterrand spoke of the possibility of a European deterrent: "The debate on the defence of Europe raises unresolved problems that will have to be resolved. Only two Community countries possess nuclear weapons. Is it possible to devise a European doctrine? This question will very soon become one of the major questions in the construction of a common European defence." But he obtained no concrete result.[80] In fact at the time, Germany considered France "incapable of providing adequate nuclear protection in the near term, so they will continue to rely on the United States for a nuclear guarantee."[87]

In 1994 Mitterrand let it be known that the range of the airborne nuclear missile was 300 km (190 mi).[80]

On 8 April 1992, President Mitterrand announced a moratorium on nuclear testing, but on 13 June 1995, his newly elected successor, Jacques Chirac, declared that eight nuclear tests would take place between September 1995 and January 1996. The purpose of these tests was to gather enough scientific data to simulate future tests. A wave of international protest broke out. On January 29, 1996, in a press release, the French President announced that, following the sixth test (on January 27 on the Fangataufa atoll in Polynesia) of the eight originally planned, France was putting an end to nuclear testing. With this last test, France has carried out 210 explosions since acquiring atomic weapons in 1960. Following the end of this last test campaign, France signed the Comprehensive Nuclear Test Ban Treaty (CTBT) on September 24, dismantling its test facilities in the Pacific. Parliament ratified the CTBT on April 6, 1998, committing France never again to carry out nuclear tests.

Little is known about the content of the nuclear cooperation agreement between France and the United States signed by Jacques Chirac and Bill Clinton in 1996.[85]

Since 1964, authority for the use of nuclear forces had been held by the president. In 1996 a new decree made the Chief of Defence Staff (CDS) solely responsible for nuclear operations.[80]

In 1996, the surface-to-surface component of the nuclear triad was abandoned, with the deactivation of the 18 missile silos on the Plateau d'Albion in Vaucluse[88] and the 30 Hadès missiles stored in Meurthe-et-Moselle. The sea-to-surface and air-to-surface components have been retained, but with a reduced number of delivery systems. As part of a new strategy of strict sufficiency, the Mirage IVs leave the strategic role, and the number of SNLEs drops from six to four with the commissioning of the Le Triomphant class.

President Nicolas Sarkozy continued this policy by disbanding one of the three Mirage 2000N squadrons.[citation needed]

At the start of the 21st century, France had almost halved its arsenal, but was continuing to modernize its nuclear delivery systems and effectors. Since full-scale testing is no longer possible, the reliability of nuclear warheads is ensured by cold firing under the Explosion Modeling Simulation programme.

As late as 2009, academics wondered about an integrated European defence policy and concluded that the question could not be answered without addressing the French nuclear programme, which few on the continent wished to do.[89]

NATO's November 2010 Strategic Concept encouraged the French nuclear posture.[90]

As recently as 2015, Francois Hollande said: "The international context does not allow for any weakness... The era of nuclear deterrence is therefore not over... In a dangerous world—and it is dangerous—France does not want to let down its guard... The possibility of future state conflicts concerning us directly or indirectly cannot be excluded."[91]

After the February 2016 Munich Security Conference and especially the victory of Donald Trump in November 2016, German thought turned toward co-operation with the French on a nuclear umbrella for Europe.[92]

2010 Lancaster House treaty

[edit]On November 2, 2010, a defense and security cooperation agreement between France and the UK was signed under the Lancaster House Treaties. This provided for a joint facility at Valduc (France) to "model the performance of nuclear warheads and associated equipment, to ensure their long-term viability, safety and security". A joint technology development center at Aldermaston (UK) supported the project.[93]

2020 state

[edit]In 2020, France had less than 300 nuclear weapons and spent 12.5% of its military budget on its nuclear weapons programme, which was split between submarine launched ballistic missiles and airborne cruise missiles. As of 2020, France had no missile shield programme. French nuclear deterrence policy has been published in the 1994, 2008 and 2013 Defence White Papers, as well as the presidential speeches of 8 June 2001 (Chirac), 19 January 2006 (Chirac), 21 March 2008 (Sarkozy) and 19 February 2015 (Hollande).[80]

French doctrine has a devolutionary principle, in case the President is somehow disabled; the Prime Minister is the first devolutionary.[80]

After Macron's 2020 speech

[edit]French president Emmanuel Macron delivered a 9000-word speech to an assembly of military chiefs in February 2020 at the Ecole de Guerre.[94][95][96][97][98][99][100] For the first time in history, he used this occasion to invite European allies to participate in the French weapons programme.[101] Some saw this as a call for "joint nuclear deterrence".[102] Others saw in his speech a warning that Europeans could not remain aloof from the arms race that had just broken free.[103][104]

In his February 2020 speech, Macron repeated long-established French doctrine, in which they "consider that all their nuclear forces are strategic, and that any use of nuclear weapons would be of a strategic nature in that it would bring about a profound transformation in the nature of the conflict." The foundations of French deterrence remain unchanged.[80]

His speech was ill-received by NATO Secretary-General Jens Stoltenberg one week later at the 2020 Munich Security Conference. It was remarked that French nuclear forces had never played a role with NATO, allies of which depend for their nuclear umbrella on the US and UK. France has always prided itself on the independence of its nuclear forces.[105] Macron reiterated his offer to European leaders: "We need a European strategy that renews us and turns us into a strategic political power."[105] However, the Europeans had little interest in the 25 years until that date.[80] A 2016 article published in the Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung suggested three possibilities, none of which included the French, and academic research over the next four years found little sympathy in German circles for the French position.[106][107] In fact, some politicians with the German SPD party wanted the US to remove its nuclear weapons and leave the continent, ex-France, defenceless.[108] A Harvard professor supported American withdrawal from the continent, irrespective of allied demands.[109]

Over the subsequent two years, it became apparent that Macron's offer was not as generous as it seemed at first.[110] In March 2023 German politicians were wary, even as they questioned the US nuclear umbrella.[111] Some have said that: "[B]ecause its nuclear arsenal is rather small and not very flexible, Paris would have to respond to a Russian conventional attack against, say, the Baltic states by threatening the use of strategic nuclear weapons against Russian cities. And it would thereby have to accept a Russian nuclear retaliatory strike against French territory. Thus, even in a world in which the United States no longer provided nuclear deterrence for Europe, it is unlikely that France's allies would unconditionally entrust Paris with their security."[111]

President Biden's 2022 idea of "integrated [nuclear] deterrence" was unable to convince France.[112]

At the Munich Security Conference in February 2024, Stoltenberg repeated his plea for stasis, even in the wake of Donald Trump's unfortunate remarks.[113] However, his remarks came after the cat had been let out of the bag.[114]

Collaborations in the 20th century

[edit]With Germany and Italy

[edit]In 1955, France initiated cooperation with the Federal Republic of Germany to build a uranium enrichment plant. At the Messina Conference (June 1955), France was also considering a Europe-wide expansion. In an attempt to derail this project, the United States offered to supply European countries with a few kilos of enriched uranium at a preferential rate. France tried to extend this cooperation to Italy (tripartite agreement of November 28, 1957).[51] Each country had its own objectives:

- Federal Germany wanted to acquire a national nuclear arsenal. Although, under the Paris Accords (1955), West Germany was not allowed to produce nuclear weapons (but also bacteriological and chemical weapons) on its own territory, it was not forbidden to possess them, provided they were produced abroad. What's more, the Paris agreements did not prohibit West Germany from conducting research in this field.[51] Moreover, it had a minister responsible for atomic questions: Franz Josef Strauß, a supporter of nuclear armament in the FRG and future Minister of Defense;

- Italy wanted to build a European nuclear arsenal, in order to rebalance forces within NATO;[51]

- France wanted an enrichment plant to be built on a European scale, to save money. Prompted by Jacques Chaban-Delmas (then Minister of Defense), this collaboration was also intended to reduce dependence on the United States. It may also have been intended to put an end to Anglo-American agreements.[51]

This collaboration was interrupted in June 1958 when General de Gaulle came to power.[51]

With Israel

[edit]In 1955, Israeli Prime Minister David Ben-Gurion declared his intention to equip the Israeli state with atomic weapons. Israel's aim was to obtain a guarantee of its existence and survival from the United States,[51] by means of atomic weapons. The establishment of the Socialist Mollet government in February 1956 enabled him to envisage collaboration with France. Guy Mollet, driven by his socialist ideals, was keen to help Israel survive. The conventional weapons supplied by France would not have been enough for Israel to face the Arab countries indefinitely.[51] On September 13, 1956, Pierre Guillaumat and Francis Perrin met Professor Ernst David Bergmann (in charge of Israel's military atomic program) and Shimon Peres (representing Defense Minister - and Prime Minister - Ben Gurion) to discuss the construction of a research reactor in the Negev desert.[51]

Cooperation between France and Israel intensified with the arrival of Maurice Bourgès-Maunoury as Prime Minister in May 1957. In mid-1957, an agreement was reached for the construction in Israel of a nuclear reactor equivalent to the G1 reactor at Marcoule (producing 10 to 15 kg of plutonium per year). Work began six months later at Dimona.[51] Like the Franco-Italo-German cooperation, this collaboration was interrupted by the arrival in power of General de Gaulle, who decided in 1961 to stop all French aid for the plutonium separation plant and to complete construction of the Dimona reactor.[115]

With South Africa

[edit]From 1963 onwards, an agreement between France and South Africa[116] enabled France to source uranium "free of use", circumventing the de facto ban imposed by the United States.

With the United Kingdom

[edit]Unlike the UK and China, which went from nuclear to thermonuclear in five and three years respectively, France spent more than eight years (1960-1968) doing the same.[117] A number of factors may explain this particular slowness:[118]

- a certain isolation of French scientists from their allies in the early 1960s, resulting from the diplomatic isolation of Gaullist policy;

- the refusal of France's young scientific elite to work for the nuclear weapons industry, even though the development of the H-bomb required much more advanced fundamental research than for the A-bomb;

- a struggle for influence between the directors of the CEA's Military Applications Division, combined with a vertical organization ill-suited to the complexity of a thermonuclear device.

When, in April 1967, the solution to nuclear fusion was finally found by the young engineer Michel Carayol, it was not adopted.[119]

The H-bomb against common market access

[edit]On July 18, 1963, during Pierre Messmer's visit to London, the British Defense Minister offered nuclear cooperation and NATO reform in exchange for access to the European common market, which de Gaulle refused.[120]

In September 1967, Great Britain reiterated its offer, which, due to France's thermonuclear embarrassment, was accepted. London gave up the secrets of the H-bomb through the physicist William Cook, who, answering questions from French scientists, confirmed that the solution proposed by Carayol was the right one.[121]

With the United States

[edit]Following World War II, the United States sought to prevent nuclear proliferation. At first, they tried, in vain, to trade technical assistance for the closest possible coordination of the eventual use of the bomb, then they somewhat favored the French program when the credibility of their nuclear umbrella was undermined by the launch of the first Soviet intercontinental ballistic missile and Sputnik in 1957.[122] They later realized that the French nuclear program was inexorable, and from 1973 onwards they changed their policy to favor its development,[116] even though the Atomic Energy Act of 1954 officially forbade the transfer of military technologies.[51]

1950s

[edit]In the 1950s, the United States tried to dissuade France from building an atomic bomb. Nevertheless, the Eisenhower administration provided technical assistance, at different levels of development, in four areas:

- open information,

"The Smyth Report, published on August 16, 1945 by the American government, was a good source of information for the French. This report showed how the Americans had succeeded in building their atomic bombs.[51] The "United Nations Conferences on the Peaceful Uses of Atomic Energy"[123] also provided useful information. The first conference (August 1955) was accompanied, on the American side, by the declassification of numerous documents providing theoretical information. The second conference (September 1958) provided more practical information, in particular on the notion of critical mass.[51]

- visit to the Nevada Atomic Test Range,

"As early as May 1955, Colonel Pierre Marie Gallois visited the Nevada Test Site (NTS). In April 1957, General Charles Ailleret (Joint Commander of Special Weapons) made another visit. This enabled him to understand the organization of such tests and to validate the organization envisaged for the Sahara test site.[51]

- high-speed measuring equipment,

"In February 1958, thanks to good relations between Presidents Felix Gaillard and Eisenhower, General Ailleret, Colonel Buchalet and Professor Yves Rocard (CEA) visited the NTS as part of the Aurore mission. While part of the mission was devoted to meetings apparently aimed at dissuading France from building an atomic bomb, technical meetings enabled the French delegation to learn more about explosion diagnosis equipment. And finally, ultra-fast electronic measuring devices were brought back to France, where they had been lacking"[51][124]

- enriched uranium,

"On December 25, 1957, Pierre Guillaumat (General Administrator of the CEA) met with Admiral Elliott B. Strauss to discuss the delivery of enriched uranium to build a submarine nuclear reactor. Strauss about delivering enriched uranium to build a submarine nuclear reactor. Admiral Strauss sought to dissuade the CEA from building its own uranium enrichment plant, and the United States agreed to supply the fuel, but not directly for a submarine. Cooperation in this area therefore remained very limited.[51] On May 7, 1959, the Americans did indeed supply enriched uranium, enabling the prototype French naval reactor (PAT), built at the Cadarache center to meet the terms of the contract, to diverge in August 1964."

1960s

[edit]

The 1960s were the years of Charles de Gaulle's presidency. President de Gaulle wanted to guarantee France's total independence in nuclear matters. Although pragmatically attached to the Western military alliance, he distanced himself from it as the Strike Force was organized. In May 1959, American tactical nuclear weapons were evacuated from France. This policy did not prevent continued collaboration with the United States, since for Washington it was an additional means of monitoring the French program,[nb 1] and for Paris an opportunity to save time and money. It wasn't until March 1966 that Franco-American relations hit rock bottom, when De Gaulle withdrew France from NATO's integrated command.

U.S. nuclear weapons in the service of NATO

[edit]In the first half of the 1960s, the French Forces in Germany (FFA) had the opportunity to practice handling nuclear weapons with American tactical weapons under double-key within the framework of NATO. The Model 59 mechanized divisions each had two batteries of two Honest John missiles from July 1960, for a total of 20 launchers (1965) in service until 1966;[125] the 520th and 521st Engine Brigades of the FFA in Baden-Württemberg deployed eight batteries of Nike-Hercules surface-to-air missiles from 1960 to 1966,[126] and the F-100 Super Sabre aircraft of the 11th Fighter Wing based at Bremgarten and Lahr-Hugsweier carried Mk-28 tactical bombs between 1963 and 1964.[127]

American weapons in the service of France

[edit]

Even though Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara was opposed to the development of independent nuclear forces within NATO, in July 1962 the Kennedy administration authorized the sale of twelve C-135F Stratotankers to the developing French strategic air force. The Boeing aircraft, essential to the Mirage IV mission, enabled France to make substantial savings by avoiding the need to develop its own tanker aircraft.[nb 2][128]

The purchase of American equipment also enabled French engineers to make faster progress by studying it. In the field of electromagnetic warfare, exchanges between the US Air Force and the French Air Force were particularly fruitful on both sides of the Atlantic.[129]

The cloak of secrecy had its other benefits as well:

"The political presentation of the independence of the French nuclear deterrent [...] would be tarnished by the discovery that we benefit from American technical support!"

— Valéry Giscard d'Estaing, Memoirs.[130]

Elected in 1969, improving relations with France became one of President Richard Nixon's foreign policy objectives. His administration reversed the U.S. policy of opposing France's nuclear program.[131]

As a result, in the early 1970s, the United States took the initiative in discussing military nuclear issues with France. These discussions were also a way for the Americans to learn more about France's nuclear arsenal. What's more, improving France's nuclear force would strengthen the United States' strategic position vis-à-vis the Soviet Union.[131] In addition to being supposedly kept secret from the international community, these discussions, and the subsequent assistance provided, took place without informing either the U.S. Congress or the State Department. The Atomic Energy Act prohibited the transfer of nuclear weapons technology. However, the Americans kept the British informed of French developments.

In the end, this assistance, though limited, saved time and money for the French military nuclear program. It continued under the Ford administration, and remained unknown to the public until 1989, when Richard Ullman published his article "The Covert French Connection" in Foreign Policy magazine.[131]

On May 26, 2011, National Security Archives archivist William Burr, in conjunction with the Nuclear Proliferation International History Project, published a report confirming the broad outlines of Ullman's article published twenty years earlier. The report, based on declassified documents, shows that U.S.-French cooperation was even earlier than Ullman's article claimed.[85]

Pompidou

[edit]Georges Pompidou's visit to Washington in February 1970[132] marked the resumption of Franco-American relations. Pompidou acknowledged France's strategic weakness and the possibility that French nuclear missiles might not be able to reach their targets. While Pompidou does not directly ask for American help, he does point out that the "Franco-American committee for technological exchanges" is at a standstill. Nixon recognized that the "nuclear question" could be the subject of discussions on cooperation. Subsequently, Secretary of Defense Melvin Laird suggests providing France with information on improving missile safety and on materials for the atmospheric re-entry phase. He remains more moderate on the transfer of astronomical navigation technology.[85]

In June 1970, the Assistant Secretary of Defense for Research and Engineering, John S. Foster Jr., made a trip to Paris to meet the Delegate General for Armaments at the Ministry of the Armed Forces, Jean Blancard. A list of French requirements is submitted. It covers land and submarine missile development, including manufacturing techniques, solid rocket motor reliability and atomic-resistant materials for atmospheric re-entry vehicles. Foster makes it clear that there will be no help on celestial navigation technology, but possibly on inertial guidance for submarine missiles.[85]

The White House took almost a year to decide on the French request, as it first wanted to review its policy on military aid to France. The answer could not be negative, since it was the United States that had taken the initiative in the 1970 missile talks. So, in March 1971, Nixon approved a minimum aid program: the U.S. would assist France in improving existing systems, but not in developing new ones. This response was transmitted by the State and Defense Departments in April 1971.[85]

A delegation led by Foster made a second visit to France in June 1971. Discussions centered on how Washington could help the French nuclear missile program. The French asked for assistance in improving safety and operability through support on technical problems ranging from propulsion to electrical connectors. An operating rule was agreed: the French would send descriptions of their technical problems, and the Americans would advise them. The American delegation is taken to Bordeaux to visit the missile production facilities and see the missiles themselves. The French were apparently satisfied with the technical exchanges authorized by Nixon in 1971.[85]

In July 1972, Defense Minister Michel Debré made an official visit to the United States. While the press speculated on the possibility of discussions on nuclear cooperation, Debré denied it, and at the time no information on such discussions appeared in the press. At a meeting with Henry Kissinger, Debré asked for information on the USSR's anti-ballistic missiles. Kissinger was in favor, but considering that the Administration might object, suggested that the French ambassador not make a formal request. State Department officials are kept out of Debré's discussions with the White House and the Pentagon. They learn, however, that a new list of requests has been sent to Foster, and that these concern highly sensitive subjects (miniaturization of nuclear warheads, use of nuclear-powered ballistic missile submarines, etc.).[85]

After Debré's visit, the French continued to ask for more information. In March 1973, on the advice of Melvin Laird, Richard Nixon authorized the transfer of information on:

- nuclear effects simulators (and sales of small simulators);

- missile hardening techniques and re-entry vehicles;

- soviet anti-ballistic missiles.

Foster also suggested providing information on early warning systems to reinforce the deterrent character of the French nuclear force.[85]

At the end of May 1973, at a meeting in Iceland between Kissinger, Nixon and Pompidou, the latter requested that the discussions, hitherto limited to missile technology, be extended to nuclear weapons technology.[133] As a result, the new Minister of the Army, Robert Galley, travelled to the US for secret talks with Kissinger and the new Secretary of Defense, James Schlesinger. Galley explained to Kissinger that France wanted information on:

- missile penetration, including hardened re-entry vehicles, penetration aids and multiple warhead missiles for submarines;

- the size and mass of accelerated detonators;

- underground testing in the United States.

For the French, this meant developing a new generation of missiles.[85]

To avoid having to seek authorization from the U.S. Congress (and thus circumvent the Atomic Energy Act of 1954), Kissinger and Galley agreed that the U.S. would confine itself to "advice in the negative" (it is not known who proposed this type of agreement), i.e. the Americans would merely criticize the ideas submitted by the French. These discussions continued for four years. They had to remain secret so as not to complicate relations between the United States and its other allies, who might then ask for the same treatment. Neither the State Department nor Congress would be informed.[85]

A ballistic missile can carry several warheads, enabling it to strike different targets in the same area. Although Kissinger was aware of the limits of the French program and of France's potential role in dissuasion, he decided to moderate the transfer of information in order to give the French the impression that discussions with Galley were progressing. However, at the beginning of 1975, the French were concerned about the slow pace of the return of information. The Americans replied that there was nothing wrong, and that it was simply a matter of detailed analysis of their requests. Some requests are in any case difficult to satisfy, such as the use of the Nevada site for underground testing. On this point, in mid-1975, President Ford nevertheless asked to study the possibilities of helping the French conduct underground tests. He also authorized a program of assistance that included:

- improving the safety, operability and reducing the nuclear vulnerability of strategic missiles;

- the hardening of missiles and re-entry vehicles;

- multi-warhead re-entry vehicles (provided they are aimed at the same target);

- fundamental knowledge of materials behavior related to nuclear weapons design.

Ford, however, prohibited the disclosure of sensitive information and the use of the Nevada site to display re-entry vehicle materials.[85]

The flow of information continued to be limited. A few months later, President Valéry Giscard d'Estaing expressed his concern to Ford and Kissinger. Kissinger explained this by the reluctance of the Pentagon and Congress. The latter would take a dim view of the White House authorizing the export of high-performance computers. While a decision on computers would have to wait several months, assistance was forthcoming on underground testing technologies, multiple-headed re-entry vehicles and submarine vulnerability.[85]

1980 to 2000

[edit]Little is known about the cooperative ventures of the 1980s and 1990s, or about the content of the nuclear cooperation agreement between France and the United States signed by Jacques Chirac and Bill Clinton in 1996.[85]

Notes

[edit]- ^ On July 15, 1965, an RF-101 Voodoo based in France flew over the Pierrelatte military plant. From 1966 to 1968, C-135s based in Hawaii collect samples from nuclear tests in the Pacific.

- ^ If France hadn't had access to American tankers, it could have adapted the Caravelle or built a longer-range strategic bomber, both of which would have been very costly.

References

[edit]- ^ Mallevre 2006, p. 10

- ^ "(Wilhem Conrad) Röntgen & les rayons X". CNRS (in French). Retrieved February 15, 2014.

- ^ Pire, Bernard. "Becquerel, Antoine Henri (1852-1908)". Encyclopædia Universalis (in French). Retrieved February 15, 2014.

- ^ a b c Mallevre 2006, p. 11

- ^ Mallevre 2006, p. 12

- ^ a b Mallevre 2006, p. 13

- ^ a b Mallevre 2006, p. 14

- ^ Reuss 2007, p. 17

- ^ a b c d Mongin 1993, p. 13

- ^ "Le Laboratoire de Synthèse Atomique, la recherche fondamentale et la responsabilité du scientifique". Union rationaliste (in French). Archived from the original on 2018-04-28. Retrieved 2017-03-19.

- ^ Gambaro, Ivana (1996). "Les laboratoires de F. Joliot entre la physique et la biologie". Atti del XVI Congresso nazionale di storia della fisica e dell'astronomia (in French). CNR.

- ^ Bendjebbar 2000, p. 29

- ^ Bendjebbar 2000, p. 33

- ^ Weart 1980, pp. 215–216

- ^ Bendjebbar 2000, pp. 36–37

- ^ Bendjebbar 2000, p. 39

- ^ Bendjebbar 2000, p. 62;79

- ^ Bendjebbar 2000, pp. 41–43

- ^ Weart 1980, pp. 269–270

- ^ Bendjebbar 2000, p. 102

- ^ Bendjebbar 2000, pp. 104–105

- ^ Weart 1980, p. 282

- ^ "Histoire du centre de Saclay". CEA Paris-Saclay. 19 October 2013. Retrieved 2017-03-17.

- ^ Bendjebbar 2000, pp. 66–67

- ^ Bendjebbar 2000, pp. 72–73

- ^ Bendjebbar 2000, pp. 74–78

- ^ Bendjebbar 2000, p. 86

- ^ a b c d e Mongin 1993, p. 14

- ^ Giovachini, Laurent (2000). L'Armement français au xxe siècle: Une politique à l'épreuve de l'histoire. Les Cahiers de l'armement (in French). Paris: Éditions Ellipses. p. 71. ISBN 978-2-7298-4864-4.

- ^ Bendjebbar 2000, pp. 98–99

- ^ "French Nuclear Weapons". GlobalSecurity.org. Retrieved 17 May 2011.

- ^ "Ordonnance no 45-2563 du 18 octobre 1945 modifiée portant création du Commissariat à l'énergie atomique (CEA)". La direction des systèmes d'information (DSI) (in French). Archived from the original on 20 November 2006. Retrieved 17 May 2011.

- ^ a b Mallevre 2006, p. 16

- ^ Bendjebbar 2000, p. 125

- ^ Bendjebbar 2000, p. 100

- ^ Bendjebbar 2000, p. 138

- ^ "La pile Française". Science & Vie. L'age atomique (in French). December 1950.

- ^ a b Mallevre 2006, p. 17

- ^ Robert, Pierre O. (July 1953). "La pile P2. Seconde étape vers l'autonomie atomique" (PDF). Science & Vie (430): 10–16.

- ^ Bendjebbar 2000, p. 158

- ^ "Félix Gaillard". Assemblée Nationale (in French). Retrieved 17 May 2011.

- ^ a b Mongin 1993, p. 15

- ^ Bendjebbar 2000, p. 189

- ^ Bendjebbar 2000, p. 160

- ^ a b c Mallevre 2006, p. 18

- ^ Carle, Rémy (2006). "La divergence de G1: Marcoule, 7 janvier 1956". Archives de France (in French).

- ^ "Gisements et exploitations d'uranium en Vendée" (PDF). Vendee.fr. Archived from the original (PDF) on 11 January 2012. Retrieved 18 May 2011.

- ^ "Gisements et exploitations Saint-Priest-la-Prugne en Forez". francenuc.org. Retrieved 18 May 2011.

- ^ "Site industriel de Bessines en Limousin". francenuc.org. Retrieved 18 May 2011.

- ^ Lacotte, R. (1966). "Le complexe industriel de Bessines" (pdf). Norois. 49: 73–81. doi:10.3406/noroi.1966.7281. Retrieved 18 May 2011.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad Mongin, Dominique (1993). "Aux origines du programme atomique militaire français". Matériaux pour l'histoire de notre temps (in French). 31 (31): 13–21. doi:10.3406/mat.1993.404097 – via Persée.

- ^ "Chronologie de la politique de défense nationale". Vie Publique (in French). Archived from the original on 2011-05-26. Retrieved May 18, 2011.

- ^ Bendjebbar 2000, pp. 195–197

- ^ a b Billaud 2017, p. 24

- ^ Duval, Marcel & Mongin, Dominique (1993). Histoire des forces nucléaires françaises depuis 1945. Presses Universitaires de France. p. 36.

- ^ Bendjebbar 2000, pp. 200–201

- ^ Mallevre 2006, p. 19

- ^ Villain, Jacques (2014). Le livre noir du nucléaire militaire. Fayard. p. 315.

- ^ "Genèse de la DAM". pbillaud.fr. Archived from the original on 28 October 2009. Retrieved 18 May 2011.

- ^ Wall, Irwin M. (2001). France, the United States, and the Algerian War. Berkeley: University of California Press. p. 158. ISBN 0520225341.

- ^ Vaïsse, Maurice (1998). La Grandeur. Politique étrangère du général de Gaulle (1958-1969). Fayard. p. 103.

- ^ "Conférence de presse du 14 janvier 1963 (sur l'entrée de la Grande-Bretagne dans la CEE)". Charles de Gaulle - paroles publiques. Retrieved 2017-07-01.

- ^ Cramer, Ben (2002). Le nucléaire dans tous ses états. ALiAS. p. 78.

- ^ Feaver, Peter & Stein, Peter (1987). Assuring Control of Nuclear Weapons: The Evolution of Permissive Action Links. CSIA Occasional Paper #2. Lanham, MD: University Press of America.

- ^ "Polynésie : de 1966 à 1996, près de 200 essais nucléaires aux conséquences désastreuses". TFI Info. July 28, 2021.

- ^ Heisbourg 2011, p. 174

- ^ a b "Stratégies nucléaires d'hier et d'aujourd'hui: Stratégies nucléaires françaises". leconflit.com. 9 December 2009. Retrieved 1 July 2017.

- ^ Maden, Michael D. (1991). "Franco-German Cooperative Defence: Its Logic and its Limitations". In Carlton, David & Schaerf, Carlo (eds.). The Arms Race in an Era of Negotiations. Palgrave Macmillan UK. pp. 181–198. ISBN 978-1-349-11967-7.

- ^ Heuser 1999, p. 106

- ^ Heuser 1999, p. 104

- ^ Tertrais, Bruno (2000). "La dissuasion nucléaire française après la Guerre froide : continuité, ruptures, interrogations". Annuaire Français de Relations Internationales. I. Archived from the original on 2008-03-19. Retrieved 2023-10-11 – via Université de Paris-II.

- ^ de Wailly, Henri (2004). Cette France qu'ils aiment haïr (in French). L'Harmattan. p. 31. ISBN 2-7475-7277-3.

- ^ "SSBS et MSBS". Les Fusées en Europe (in French) – via Université de Perpignan.

- ^ de Perrot 1984, p. 232

- ^ "La 4e escadre de chasse". Base aérienne 116 (in French). 21 March 2007. Archived from the original on 2011-07-20.

- ^ "La 7e Escadre et ses Escadrons". Association des Personnels et Amis de la 7e Escadre de Chasse (in French). Archived from the original on 2011-07-07.

- ^ Guide d'accueil du porte-avions Clemenceau R98 (in French). Marine Nationale.

- ^ Croulebois, Georges (1993). Pont libre!: Huit porte-avions français (in French). Éditions des 7 vents. p. 211. ISBN 287716-052-1.

- ^ Théléri, Marc (1997). Initiation à la force de frappe française (1945-2010) (in French). Stock. p. 100. ISBN 2234047005.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Tertrais, Bruno (February 2020). French Nuclear Deterrence Policy, Forces, And Future: A Handbook (PDF). Fondation pour la Recherche Stratégique.

- ^ Boureille, Patrick (2006). "L'outil naval français et la sortie de la guerre froide (1985-1994)". Revue historique des armées (in French) (245): 46–61. doi:10.3917/rha.245.0046. Retrieved 26 October 2009.

- ^ "Allocution prononcée par le Premier ministre de la France, Pierre Mauroy". CVCE (in French). 20 September 1983.

- ^ Norris, Robert S. & Kristensen, Hans M. (1 July 2010). "Global nuclear weapons inventories, 1945–2010". Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists. Retrieved 22 February 2011.

- ^ Wodka-Gallien 2014, p. 152

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n "The French Bomb, with Secret U.S. Help". National Security Archive. May 26, 2011. Retrieved 2022-03-04 – via George Washington University.

- ^ Butcher, Martin; Nassauer, Otfried & Young, Stephen (December 1998). "Nuclear futures: Western European options for nuclear risk reduction" (PDF). British-American Security Information Council.

- ^ Gunning Jr., Lt. Edward G. (December 1992). Germany and The Future of Nuclear Deterrence in Europe (PDF) (MA). Naval Postgraduate School.

- ^ Isnard, Jacques (September 17, 1996). "La dissuasion redimensionnée". Le Monde (in French). Retrieved January 10, 2018.

- ^ Jasper, Ulla & Portela, Clara (2009). "A Common Deterrent for a United Europe? Revisiting European Nuclear Discourse" (PDF). Archive of European Integration.

- ^ Nonstrategic Nuclear Weapons (Report). Congressional Research Service. May 4, 2020.

- ^ Payne, Keith B. (2015). "US Nuclear Weapons and Deterrence: Realist versus Utopian Thinking" (PDF). Air & Space Power Journal. 29 (4): 63.

- ^ Volpe, Tristan & Kühn, Ulrich (2017). "Germany's Nuclear Education: Why a Few Elites Are Testing a Taboo" (PDF). The Washington Quarterly. 40 (3): 7–27. doi:10.1080/0163660X.2017.1370317.

- ^ Gros-Verheyde, Nicolas (2 November 2010). "Les 13 points de l'accord franco-britannique sur la défense". Bruxelles2. Retrieved 10 September 2012.

- ^ Hautecouverture, Benjamin (September 2020). "President Macron on French Nuclear Deterrence". Canadian Global Affairs Institute.

- ^ "France Offers Nuclear Deterrent to All Europe". Arms Control Association.

- ^ "Macron's strategic vision for Europe". International Institute for Strategic Studies. April 2020.

- ^ Vela, Jakob Hanke & Camut, Nicolas (25 January 2024). "As Trump looms, top EU politician calls for European nuclear deterrent". Politico.

- ^ Varma, Tara (7 February 2020). "The search for freedom of action: Macron's speech on nuclear deterrence". European Council on Foreign Relations.

- ^ "Macron's strategic vision for Europe". Strategic Comments. 26 (2): iv–vi. 2020. doi:10.1080/13567888.2020.1751419. S2CID 221051946.

- ^ Kulesa, Łukasz (2021-07-06). "Weapons of Mass Debate - Polish Deterrence with Russia in the Line of Sight". Institut Montaigne.

- ^ "Macron urges EU nuclear defence strategy — with France at centre". Euronews. 8 February 2020.

- ^ Brzozowski, Alexandra (7 February 2020). "In post-Brexit push, Macron calls for European nuclear arms control agenda". Euractiv.

- ^ "Macron unveils nuclear doctrine, warns EU 'cannot remain spectators' in arms race". France 24. 7 February 2020.

- ^ "Macron: Europeans cannot remain spectators in new arms race". Al Jazeera. 7 February 2020.

- ^ a b "NATO Chief Rejects Macron Call to Put French Nukes at Center of European Strategy". Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty. February 16, 2020.

- ^ Kühn, Ulrich; Volpe, Tristan & Thompson, Bert (August 15, 2018). "Tracking the German nuclear debate". Carnegie Endowment for International Peace.

- ^ Singh, Shivani (October 1, 2019). "In America We Trust: Regional Responses to US Extended Deterrence from Obama to Trump". Institute of Peace and Conflict Studies. pp. 7–13.

- ^ Karnitschnig, Matthew (May 3, 2020). "German social democrats tell Donald Trump to take US nukes home". Politico.

- ^ "It's Time to Fold America's Nuclear Umbrella". 22 February 2024.

- ^ Schuller, Konrad (14 January 2022). "Frankreich erneuert das Angebot, mit der EU über Atomwaffen zu reden". Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung.

- ^ a b Horovitz, Liviu; Wachs, Lydia (2023). "France's nuclear weapons and Europe". SWP Comment. doi:10.18449/2023C15.

- ^ Pappalardo, David (30 January 2024). "Does France really have a problem with the concept of Integrated Deterrence?". Network for Strategic Analysis.