History of the Bulgarian language

This article needs additional citations for verification. (November 2017) |

| Part of a series on |

| Bulgarians Българи |

|---|

|

| Culture |

| By country |

| Subgroups |

| Religion |

| Language |

| Other |

The history of the Bulgarian language can be divided into three major periods:

- Old Bulgarian (from the late 9th until the 11th century);

- Middle Bulgarian (from the 12th century to the 15th century);

- Modern Bulgarian (since the 16th century).

Bulgarian is a written South Slavic language that dates back to the end of the 9th century.

Old Bulgarian

[edit]

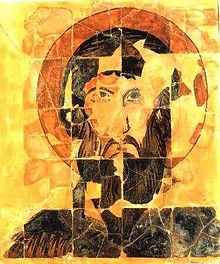

Old Bulgarian was the first literary period in the development of the language. It was a highly synthetic language with a rich declension system as attested by a number of manuscripts from the late 10th and the early 11th centuries. Those originate mostly from the Preslav and the Ohrid Literary School, although smaller literary centers also contributed to the tradition. The language became a medium for rich scholarly activity — chiefly in the late 9th and the early 10th century — with writers such as Constantine of Preslav, John Exarch, Clement of Ohrid, Chernorizetz Hrabar and Naum of Preslav (Naum of Ohrid). Most of their works are preserved through later copies, many of which are from neighboring Balkan countries or Russia.

Name

[edit]The name “Old Bulgarian” was extensively used in the late 19th and the first half of the 20th century synonymously with Old Church Slavonic to describe the literary language of a number of Slavic peoples from the 9th until the 11th century. Although "Old Bulgarian" is still used in a number of sources with the meaning "Old Church Slavonic", there is a growing tendency for the name to be applied only to the language of manuscripts from the First Bulgarian Empire (Bulgarian editions of Old Church Slavonic), excluding manuscripts from other editions.

Traits

[edit]Old Bulgarian is characterized by a number of phonetic, morphological, syntactic, and lexical traits (some of which are shared with other Slavic languages and some, such as the reflexes of *tj ([t']) and *dj ([d']), are typical only for Bulgarian):

- phonetic:

- very wide articulation of the Yat vowel (Ѣ); still preserved in the archaic Bulgarian dialect of the Rhodope mountains;

- Proto-Slavonic reflexes of *tj ([tʲ]) and *dj ([dʲ]):

| Proto-Slavic | Old Church Slavonic | Bulgarian | Czech | Macedonian | Polish | Russian | Slovak | Slovenian | Serbo-Croatian |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| *dʲ | ʒd | ʒd | z | ɡʲ | dz | ʒ | dz | j | dʑ |

| *tʲ (also from earlier *ɡt/kt) | ʃt | ʃt | ts | kʲ | ts | tɕ | ts | tʃ | tɕ |

- use of ra-, la- for the Proto-Slavic õr-, õl-

- use of s for the Proto-Slavic ch before the Proto-Slavic åi

- use of cv-, dzv- for the Proto-Slavic kv’-, gv’-

- morphosyntactic

- use of the dative possessive case in personal pronouns and nouns: рѫка ти; отъпоуштенье грѣхомъ;

- descriptive future tense using the verb хотѣти;

- use of the comparative form мьнии (smaller) to mean younger.

- use of suffixed demonstrative pronouns (тъ, та, то). These developed later into suffixed definite articles.

- orthographical:

- original [ы] and [ъi] merged to [ы]

- sometimes the use of letter 'Ѕ' (dz) was unified with that of 'З' (z)

- verb forms naricają, naricaješi were substituted or alternated with naričą, naričeši

- lexical:

Middle Bulgarian

[edit]In the period between 12th and 15th centuries the structure of the language changed quite radically. Few of these changes can still be observed in contemporary written records, thanks to the tendency towards archaicism driven by a desire to preserve the purity of the Cyrilo-Methodian tradition.

- The phonetic features of Middle Bulgarian include:

- Changes to the nasal vowels, which lose their nasal element in the majority of the Bulgarian dialects. The frequent confusion of the letters for the front and back nasal vowels suggests that the two vowels were phonetically very similar.

- As in other Balkan Slavic languages /ы/ becomes /и/ (although it is thought this change occurred later in Bulgarian).

- The yat vowel falls together with /e/ in Western dialects, with some manuscripts confusing it not only with e but also with the front nasal letter. In Eastern dialects the situation is more complex, as is reflected in the treatment of jat in the modern literary language (based on the Eastern pronunciation, i.e. [ja] when under stress and before a hard consonant, [ɛ] everywhere else).

- As for consonants, the East/West distinctions of hardness and softness become more clearly defined, with the hardening of consonants occurring more in the West while the Eastern dialects preserve the opposition hard/soft for most consonants.

The language underwent some morphological changes as well: starting from the time of the Second Bulgarian Empire a confusion of case endings is to be observed along with the increasing use of prepositions in syntax. This linguistic tendency resulted in the gradual loss of the complex Slavic case system, rendering Bulgarian and Macedonian significantly more analytic than their relatives. Scholars dispute whether this has anything to do with phonetic changes, such as the confusion of the nasals, or whether it is purely due to the influence of grammar developments across the Balkans. Also dating from the High Middle Ages is the use of the prefixes по- and най- to indicate comparative and superlative degrees of the adjective.

The earliest signs of post-positive definite article dates from the early 13th century with the Dobreyshevo Gospel (Добрейшево Евангелие) where the construction "злыотъ рабъ" ("the evil person") was used. Old Bulgarian relative pronouns иже, яже and еже ("which," masculine, feminine, neuter) were at that time replaced by interrogative pronouns with the suffix -то: който, която, което.

A new class of verbs developed with stems in -a-, conjugating like the old athematic verbs, e.g. имам, имаш, etc., (to have). Another characteristic of this period is the emergence of a shortened form of the future tense marker - "ще" in modern literary language and "че," "ке," and "ше" in dialect forms. The marker originates from the 3rd person singular present tense form of the verb "hotjeti" - to want). The Renarrative verb form possibly appeared around the end of the Second Bulgarian Empire, though it could also be attributed to subsequent Turkish influence.

A language of rich literary activity, it served as the official administration language of the Second Bulgarian Empire, Walachia, Moldavia (until the 19th century) and the Ottoman Empire (until the 16th century).[1] Sultan Selim I spoke and used it well.[2]

Modern Bulgarian

[edit]

Modern Bulgarian dates from developments beginning after the 16th century; particularly grammar and syntax changes in the 18th and 19th centuries. Present-day written Bulgarian language was standardized on the basis of the 19th-century Bulgarian vernacular from Central Eastern Bulgaria.

Bulgarian, along with the closely related Macedonian language (collectively forming the Eastern group of South Slavic), has several characteristics that set it apart from all other Slavic languages:[3][4] changes include the elimination of case declension, the development of a suffixed definite article (see Balkan language area), and the lack of a verb infinitive, but it retains and has further developed the Proto-Slavic verb system. Various evidential verb forms exist to express unwitnessed, retold, and doubtful action.

See also

[edit]- Bulgarian language

- Macedonian language

- Bulgarian dialects

- Bulgarian lexis

- Bulgarian grammar

- Torlakian dialect

- Slavic dialects of Greece

References

[edit]- ^ (https://www.researchgate.net/publication/359950277_Written_Languages_in_Wallachia_during_the_Reign_of_Neagoe_Basarab_1512-1521)

- ^ Чилингиров, Стилиян [in Bulgarian] (2006). "Какво е дал българинът на другите народи". p. 60.

- ^ Katzner, Kenneth (2002). The Languages of the World (3rd ed.). Routledge.

Macedonian is closely related to Bulgarian and is considered by some to be merely a dialect of that language.

- ^ Fortson, Benjamin W. (2009). Indo-European Language and Culture: An Introduction (2nd ed.). Wiley-Blackwell. p. 431. ISBN 978-1-4051-8896-8.