History of Amazon

Amazon is an American multinational technology company which focuses on e-commerce, cloud computing, and digital streaming. It has been referred to as "one of the most influential economic and cultural forces in the world",[1] and is one of the world's most valuable brands.[2]

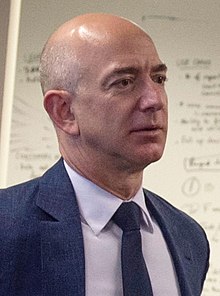

Amazon was founded by Jeff Bezos from his garage in Bellevue, Washington,[3] on July 5, 1994. Initially an online marketplace for books, it has expanded into a multitude of product categories: a strategy that has earned it the moniker "the everything store".[4] It has multiple subsidiaries including Amazon Web Services (cloud computing), Zoox (autonomous vehicles), Kuiper Systems (satellite Internet), Amazon Lab126 (computer hardware R&D). Its other subsidiaries include Ring, Twitch, IMDb, MGM Holdings and Whole Foods Market.

Founding

[edit]The company was created as a result of what Jeff Bezos called his "regret minimization framework" – to avoid regretting, in his old age, not having tried to participate in the emerging internet with his own startup.[5] In 1994, Bezos left his job as a vice president at D. E. Shaw & Co., a Wall Street firm, and moved to Seattle, Washington, where he began to work on a business plan[6] for what would become Amazon.com.

On July 5, 1994, Bezos initially incorporated the company in Washington state with the name Cadabra, Inc.[7] After a few months, he changed the name to Amazon.com, Inc, because a lawyer misheard its original name as "cadaver".[8] Bezos selected this name by looking through a dictionary; he settled on "Amazon" because it was a place that was "exotic and different", just as he had envisioned for his Internet enterprise. The Amazon River, he noted, was the biggest river in the world, and he planned to make his store the biggest bookstore in the world.[9] Additionally, a name that began with "A" was preferred because it would probably be at the top of an alphabetized list.[9] Bezos placed a premium on his head start in building a brand and told a reporter, "There's nothing about our model that can't be copied over time. But you know, McDonald's got copied. And it's still built a huge, multibillion-dollar company. A lot of it comes down to the brand name. Brand names are more important online than they are in the physical world."[10]

In its early days, the company was operated out of the garage of Bezos's house on Northeast 28th Street in Bellevue, Washington.[11]

Online bookstore and IPO

[edit]After reading a report about the future of the Internet that projected annual web commerce growth at 2,300%, Bezos created a list of 20 products that could be marketed online. He narrowed the list to what he felt were the five most promising products, which included: compact discs, computer hardware, computer software, videos, and books. Bezos finally decided that his new business would sell books online, because of the large worldwide demand for literature, the low unit price for books, and the huge number of titles available in print.[12] Amazon was founded in the garage of Bezos' rented home in Bellevue.[9][13][14] Bezos' parents invested almost $246,000 in the start-up.[15][16]

On July 16, 1995, Amazon opened as an online bookseller, selling the world's largest collection of books to anyone with World Wide Web access.[17] The first book sold on Amazon.com was Douglas Hofstadter's Fluid Concepts and Creative Analogies: Computer Models of the Fundamental Mechanisms of Thought.[18] In the first two months of business, Amazon sold to all 50 states and over 45 countries. Within two months, Amazon's sales were up to $20,000 per week.[19] In October 1995, the company announced itself to the public.[20] In 1996, it was reincorporated in Delaware. Amazon issued its initial public offering of capital stock on May 15, 1997, at $18 per share, trading under the NASDAQ stock exchange symbol AMZN.[21]

Barnes & Noble sued Amazon on May 12, 1997, alleging that Amazon's claim to be "the world's largest bookstore" was false because it "...wasn't a bookstore at all. It's a book broker." The suit was later settled out of court and Amazon continued to make the same claim.[22] Walmart sued Amazon on October 16, 1998, alleging that Amazon had stolen Walmart's trade secrets by hiring former Walmart executives. Although this suit was also settled out of court, it caused Amazon to implement internal restrictions and the reassignment of the former Walmart executives.[22]

In 1999, Amazon first attempted to enter the publishing business by buying a defunct imprint, "Weathervane", and publishing some books "selected with no apparent thought", according to The New Yorker. The imprint quickly vanished again, and as of 2014[update] Amazon representatives said that they had never heard of it.[23] Also in 1999, Time magazine named Bezos the Person of the Year when it recognized the company's success in popularizing online shopping.[24]

21st century

[edit]

Since June 19, 2000, Amazon's logotype has featured a curved arrow leading from A to Z, representing that the company carries every product from A to Z, with the arrow shaped like a smile.[25]

According to sources, Amazon did not expect to make a profit for four to five years. This comparatively slow growth caused stockholders to complain that the company was not reaching profitability fast enough to justify their investment or even survive in the long term. In 2001, the dot-com bubble burst, destroying many e-companies in the process, but Amazon survived and moved forward beyond the tech crash to become a huge player in online sales. The company finally turned its first profit in the fourth quarter of 2001: $0.01 (i.e., 1¢ per share), on revenues of more than $1 billion. This profit margin, though extremely modest, proved to skeptics that Bezos' unconventional business model could succeed.[26][27]

In 2011, Amazon had 30,000 full-time employees in the US, and by the end of 2016, it had 180,000 employees.[28]

In 2014, Amazon launched the Fire Phone. The Fire Phone was meant to deliver media streaming options but the venture failed, resulting in Amazon registering a $170 million loss. This would also lead to the Fire Phone production being stopped the following year. In August of the same year, Amazon would finalize the acquisition of Twitch, a social video gaming streaming site, for $970 million. This new acquisition would be integrated into the game production division of Amazon.

In June 2017, Amazon announced that it would acquire Whole Foods, a high-end supermarket chain with over 400 stores, for $13.4 billion.[29][30] The acquisition was seen by media experts as a move to strengthen its physical holdings and challenge Walmart's supremacy as a brick and mortar retailer. This sentiment was heightened by the fact that the announcement coincided with Walmart's purchase of men's apparel company Bonobos.[31] On August 23, 2017, Whole Foods shareholders, as well as the Federal Trade Commission, approved the deal.[32][33]

In September 2016, Amazon announced plans to locate a second headquarters in a metropolitan area with at least a million people.[34] Cities needed to submit their presentations by October 19, 2017, for the project called HQ2.[35] The $5 billion second headquarters, starting with 500,000 square feet and eventually expanding to as much as 8 million square feet, may have as many as 50,000 employees.[36] In 2017, Amazon announced it would build a new downtown Seattle building with space for Mary's Place, a local charity in 2020.[37]

At the end of 2017, Amazon had over 566,000 employees worldwide.[38][39]

According to an August 8, 2018, story in Bloomberg Businessweek, Amazon has about a five percent share of US retail spending (excluding cars and car parts and visits to restaurants and bars), and a 43.5 percent share of online spending in the U.S. in 2018. The forecast is for Amazon to own 49 percent of the total American online spending in 2018, with two-thirds of Amazon's revenue coming from the US.[40]

Amazon launched the last-mile delivery program and ordered 20,000 Mercedes-Benz Sprinter Vans for the service in September 2018.[41][42]

Amazon generated $386 billion in US retail e-commerce sales in 2020, up 38% over 2019. Amazon's Marketplace sales represent an increasingly dominant portion of its e-commerce business.

On November 14, 2022, it was announced that Amazon had plans to lay off 10,000 employees among its corporate and technology staff.[43] The number increased to 18,000 in a January 2023 announcement.[44] In March, Amazon announced it would eliminate an additional 9,000 jobs.[45]

On September 25, 2023, Amazon and artificial intelligence startup Anthropic announced a strategic partnership in which Amazon would become a minority stakeholder by investing up to US$4 billion, including an immediate investment of $1.25bn. As part of the deal, Anthropic would use Amazon Web Services (AWS) as its primary cloud provider and will make its AI models available to AWS customers.[46][47]

With more than one million workers employed in warehouses around the world, Amazon in 2023 started testing humanoid robots that provide partial automation of its work tasks.[48] The robots are able to position empty boxes and indicate where new ones are stored. [49]

HQ2

[edit]In November 2018, Amazon [50] announced it would open its highly sought-after new headquarters, known as (HQ2) in Long Island City, Queens, New York City,[51][52] and in the Crystal City neighborhood of Arlington County, Virginia.[53] On February 14, 2019, Amazon announced it was not moving forward with plans to build HQ2 in Queens[54] but would instead focus solely on the Arlington location. The company plans to locate at least 25,000 employees at HQ2 by 2030 and will invest more than US$2.5 billion[55] to establish its new headquarters in Crystal City as well as neighboring Pentagon City and Potomac Yard, an area jointly marketed as "National Landing." The announcement also created a new partnership with Virginia Tech University to develop an Innovation Campus to fill the demand for high-tech talent in National Landing and beyond.

COVID-19

[edit]At the end of March 2020, some workers of the Staten Island warehouse staged a walkout in protest of the poor health situation at their workplace amidst the 2020 COVID-19 pandemic. One of the organizers, Chris Smalls, was first put on quarantine without anyone else being quarantined, and soon afterwards fired from the company.[56][57][58][59][60]

The pandemic caused a surge in online shopping and resulted in shortages of household staples both online and in some brick-and-mortar stores. From March 17[61] to April 10, 2020,[62] Amazon warehouses stopped accepting non-essential items from third-party sellers. The company hired approximately 175,000 additional warehouse workers and delivery contractors to deal with the surge, and temporarily raised wages by $2/hour.[62]

Acquisition of MGM

[edit]After months of speculation due to MGM's poor financial performance from the COVID-19 pandemic's impact on the movie industry, Amazon entered negotiations to acquire MGM at an estimated $9 billion on May 17, 2021.[63] The companies agreed to the merger deal on May 26, 2021, for a total value of $8.45 billion, subject to regulatory approval. The deal would allow Amazon to add the MGM library to the Amazon Prime Video catalog, with the studio continuing to operate as a label under the new parent company.[64]

The merger was finalized on March 17, 2022, following the expiration of the FTC's review deadline[65] and having cleared the European Commission two days earlier on March 15.[66][67][68][69][70][71][72] Later that day, Amazon Studios and Prime Video SVP Mike Hopkins revealed that Amazon will continue to partner with United Artists Releasing (MGM and Annapurna Pictures' joint distribution venture), which will remain in operation to release all future MGM titles theatrically on a "case-by-case basis," while "all MGM employees will join my organization." It was also revealed that Amazon had no plans to make changes to the studio's production slate and release schedules nor make all MGM content exclusive to Prime Video, providing some hope that the studio would operate autonomously from Amazon Studios. These plans are expected to not impact the future of the James Bond franchise and its creative team. Two town halls further detailing MGM's future post-merger took place on March 18, 2022, which included one for MGM employees and one for Amazon Studios/Prime Video employees.[73] Both revealed the new interim reporting structure as part of Amazon's "phased integration plan," which would involve De Luca, Mark Burnett (Chairman of MGM Worldwide Television) and COO Chris Brearton reporting to Hopkins on behalf of the studio.[74] On April 27, 2022, it was announced that De Luca and Abdy would leave the studio.[75]

Amazon Go

[edit]On January 22, 2018, Amazon Go, a store that uses cameras and sensors to detect items that a shopper grabs off shelves and automatically charges a shopper's Amazon account, was opened to the general public in Seattle.[76][77] Customers scan their Amazon Go app as they enter, and are required to have an Amazon Go app installed on their smartphone and a linked Amazon account to be able to enter.[76] The technology is meant to eliminate the need for checkout lines.[78][79][80] Amazon Go was initially opened for Amazon employees in December 2016.[81][82][83] By the end of 2018, Amazon was operating a total of 8 Amazon Go stores located in Seattle, Chicago, San Francisco and New York.[84] As of August 2024, Amazon Go had 23 locations in New York, California, Washington, and Illinois.

Amazon 4-Star

[edit]Amazon announced to debut the Amazon 4-star in the Soho neighborhood of New York City on Spring Street between Crosby and Lafayette on September 27, 2018. The store carries 4-star and above-rated products from around New York.[85] The Amazon website searches for the most rated, highly demanded, frequently bought, and most wished for products which are then sold in the new Amazon store under separate categories. Along with the paper price tags, the online review cards will also be available for the customers to read before buying the product.[86][87] In late 2021, Amazon opened two 4-star stores in the United Kingdom. Its store at the Bluewater Shopping Centre in Kent opened in October, and its store at Westfield London opened in November.[88]

In March 2022, Amazon announced that they would be closing all 4-star stores, along with their Books and Pop Up stores, across the US and the UK, stating that they were refocusing on their grocery and fashion stores.[89]

Mergers and acquisitions

[edit]Amazon has grown through several mergers and acquisitions. The company has also invested in a number of growing firms, both in the United States and internationally.[90][91] In 2014, Amazon purchased top level domain .buy in auction for over $4 million.[92][93] The company has invested in brands that offer a wide range of services and products, including Engine Yard, a Ruby-on-Rails platform as a service company,[94] and Living Social, a local deal site.[95]

Timeline

[edit]Overview

[edit]| Time period | Key developments at Amazon |

|---|---|

| 1994–1998 | Amazon started off as an online bookstore selling books, primarily competing with local booksellers and Barnes & Noble. It IPOs in 1997. |

| 1998–2004 | Amazon starts to expand its services beyond books. It also starts offering convenience services, such as Free Super Savers Shipping. |

| 2005–2011 | Amazon moves into the cloud computing area with Amazon AWS, as well as the crowdsourcing area with Amazon Mechanical Turk. By being an early player, it eventually dominates the cloud computing scene, allowing it to control much of the physical infrastructure of the Internet.[96] Amazon also offers the Amazon Kindle for people to purchase their books as eBooks, and by 2010, more people buy ebooks than physical books from Amazon. |

| 2011–2015 | Amazon starts offering streaming services like Amazon Music and Amazon Video. By 2015, its market capitalization surpassed that of Walmart. |

Full timeline

[edit]| Year | Month and date | Event type | Details |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1994 | July 4 | Company | Amazon founded.[97] |

| 1995 | July 16 | Launch | Amazon launches its online bookstore. |

| 1997 | May 15 | Company | Amazon IPOs at $18.00/share, raising $54 million.[97] |

| 1998 | April 27 | Acquisitions | Amazon acquires the Internet Movie Database, a comprehensive repository for movie information on the Internet.[98] |

| 1998 | August 5 | Company Direction | Amazon announces that it will move beyond books.[99] |

| 1998 | December | Competition | Jack Ma launches Alibaba in China, which would later grow to dominate the Chinese online retail market, and provide an obstacle to Amazon's attempts to expand in China.[100][101] |

| 2002 | January | Product | Amazon launches Free Super Saver Shipping, which allows customers to get free shipping for orders above $99.[97] |

| 2002 | March | Legal, Competition | Amazon settles its October 1999 patent infringement suit against Barnes & Noble (over its 1-Click checkout system, which it received a patent for in September 1999). It originally charged that Barnes&Noble.com had essentially copied Amazon's 1-Click technology.[102] |

| 2003 | October | Product | Amazon launches A9.com, a subsidiary of Amazon.com based in Palo Alto, California that develops search and advertising technology.[103] |

| 2003 | December | Company | First profit announced.[104] |

| 2004 | August 19 | International | Amazon acquires Joyo, an online bookstore in China, for $75 million, which then becomes the 7th regional website of Amazon.com. joyo later becomes Amazon China.[105] |

| 2005 | February | Product | Amazon launches Amazon Prime, a membership offering free two-day shipping within the contiguous United States on all eligible purchases for a flat annual fee of $79.[97] |

| 2005 | November | Product | Amazon launches Amazon Mechanical Turk, an application programming interface (API) allowing any Internet user to perform "human intelligence" tasks such as transcribing podcasts, often at very low wages.[97] |

| 2006 | August 25 | Product | Amazon launches Amazon Elastic Compute Cloud (Amazon EC2), a virtual site farm allowing users to use the Amazon infrastructure to run applications ranging from running simulations to web hosting.[106] |

| 2006 | September 19 | Product | Amazon launches Fulfillment by Amazon (FBA), giving small businesses the ability to use Amazon.com's own order fulfillment and customer service infrastructure – and customers of Amazon.com shipping offers when buying from 3rd-party sellers.[107] |

| 2006 | Legal | Amazon agrees to settle a legal dispute with Toys R Us (over a partnership that gave Toys R Us exclusive rights to supply some toy products on Amazon's website) and pays $51 million.[108] | |

| 2006 | March | Product | Amazon launches Amazon Simple Storage Service (Amazon S3), which allows other websites/developers to store computer files on Amazon's servers.[97] |

| 2007 | August | Product | CreateSpace announces launch of Books on Demand service, which makes it easy for authors who want to self-publish their books to distribute them on Amazon.com.[109] |

| 2007 | August | Product | Amazon launches AmazonFresh, a grocery service offering perishable and nonperishable foods.[110] |

| 2007 | September 25 | Product | Amazon launches Amazon Music, an online music store and music locker.[111] |

| 2007 | November 19 | Product | Amazon launches the Amazon Kindle.[97] |

| 2009 | July 22 | Acquisitions, Competition | Amazon acquires Zappos for $850 million.[112] |

| 2009 | October 20 | Competition | Barnes & Noble announces the Nook, an eReader.[113] |

| 2010 | January | Competition | Apple introduces its own virtual bookstore, called iBooks, and then partners with five major book publishers.[114] It later convinces them to raise the price of ebooks (using the agency pricing model that gives publishers full control over ebook prices). |

| 2010 | February 1 | Competition | Microsoft launches Microsoft Azure, a cloud computing platform that will compete with Amazon AWS over cloud services. |

| 2010 | July | Product | Amazon announced that e-book sales for its Kindle reader outnumbered sales of hardcover books for the first time ever.[115] |

| 2011 | January | Acquisitions, International | Amazon acquires Lovefilm, a DVD rental service known as the Netflix of Europe.[116] |

| 2011 | February 16 | Competition | Borders Group, outcompeted by Amazon, applies for Chapter 11 bankruptcy.[117] |

| 2011 | February 22 | Product | Amazon rebrands its Amazon Video service as Amazon Instant Video and adds access to 5,000 movies and TV shows for Amazon Prime members.[118][119] |

| 2011 | March 22 | Product | Amazon launches the Amazon Appstore for Android devices and the service was made available in over 200 countries.[120] |

| 2011 | July 1 | Legal | California starts collecting sales taxes on Amazon.com purchases.[121] |

| 2011 | September | Product | Amazon launches Amazon Locker, a delivery locker system that allows users to get items delivered at specially-designed lockers.[122] |

| 2011 | September 28 | Product | Amazon announces the Kindle Fire, a tablet computer that takes aim at Apple's iPad with a smaller device that sells at $199, compared with the $499 value of Apple's cheapest iPad.[123] |

| 2012 | April | Legal | The Department of Justice files suit against Apple Inc and five major publishing houses (the "Big Five"), alleging that they colluded in 2010 to raise the price of ebooks (using the agency pricing model that gives publishers full control over ebook prices).[124] Amazon had originally set the price of ebooks at $9.99 (using the wholesale pricing model giving Amazon full control over ebook prices). |

| 2012 | March 19 | Acquisitions | Amazon acquires Kiva Systems for $775 million, a robotics company that creates robots that can move items around warehouses.[125] |

| 2012 | April | Legal | Amazon agrees to allow collection of sales taxes in both Nevada and Texas (starting on July 1), and agrees to create 2,500 jobs and invest $200 million in new distribution centers in Texas.[126] |

| 2012 | September 6 | Product | Amazon announces the Kindle Fire HD series of touchscreen tablet computers.[127] |

| 2013 | March | Acquisitions | Amazon acquires social reading and book-review site GoodReads.[128] |

| 2013 | June | International | Amazon launches in India.[129][130] |

| 2014 | July 25 | Product | Amazon launches the Amazon Fire.[131] |

| 2014 | August 25 | Acquisitions | Amazon announced its intent to acquire the video game streaming website Twitch for $970 million.[132] |

| 2014 | October | Legal | Amazon reaches agreement with Simon & Schuster, allowing the publisher to adopt the agency pricing model and set prices on its books sold on Amazon.[133] |

| 2014 | November 6 (announcement), actual rollout occurs through 2015 | Product | Amazon unveils Amazon Echo, a wireless speaker and voice command device that can take commands and queries, and be used to add items to the Amazon.com shopping cart, among other things.[134][135] The Alexa Voice Service that is built into Amazon Echo can also be added to other Amazon devices.[136] |

| 2014 | November | Legal | Amazon resolves dispute with Hachette, allowing Hachette to adopt the agency-pricing model and set prices on Hachette books sold on Amazon.[137] |

| 2015 | July | Competition, International | Alibaba announces that it will invest $1 billion into its Aliyun cloud computing arm, some of which would go into new Aliyun international data centers. This would allow Aliyun to compete with Amazon Web Services outside of China.[138] |

| 2015 | August 26 | Product | Amazon launches Amazon Underground, an Android app through which users can get gaming and other apps for free that they would otherwise have to pay for, and also get in-app purchases for free. App creator participation is voluntary. App creators are paid $0.002 for every minute a user spends in the app.[139][140][141] |

| 2015 | September 8 | Product | Amazon launches its Amazon Restaurants service that delivers food from nearby restaurants, for Amazon Prime customers in Seattle.[142][143] The service would subsequently be rolled out to many other cities. |

| 2015 | November 2 | Product | Amazon opened its first physical retail store, a bookstore in the University Village shopping center in Seattle. The store, known as Amazon Books, has prices matched to those found on the Amazon website and integrate online reviews into the store's shelves.[144] |

| 2015 | December 14 | Company | Amazon begins moving into their new headquarters campus in the Denny Triangle neighborhood of Seattle, beginning with the 38-story Amazon Tower I (nicknamed "Doppler" after the codename for Amazon Echo).[145] The three towers are scheduled to be completed by 2020. |

| 2016 | December 7 | Delivery | Amazon Prime Air (Amazon's drone-based delivery system) makes its first delivery in Cambridge in the United Kingdom. The successful delivery is announced a week later, on December 14, along with video.[146][147] |

| 2017 | June 15 | Acquisitions | Amazon acquires Whole Foods for $13.7 billion, a grocery-store chain located throughout the United States, United Kingdom, and Canada.[148] |

| 2017 | September 7 | Company | Amazon began search for Amazon HQ2, a second company headquarters to house up to 50,000 employees.[149][150] |

| 2018 | January 18 | Company | Amazon narrows down the choices of its second headquarters location to 20 places.[151] |

| 2018 | January 22 | Company | Amazon opens a cashier-less grocery store (Amazon Go) to the public.[152] |

| 2018 | September 19 | International | Amazon launches in Turkey.[153] |

| 2018 | October 2 | Company | After widespread criticism, Amazon raises its minimum wage for all U.S. and U.K. employees to $15 an hour, including Whole Foods and seasonal employees, beginning November 1, 2018.[154][155] |

| 2018 | November 13 | Company | Jeff Bezos announces that the new headquarters HQ2 will be split between New York City and Northern Virginia.[156] |

| 2019 | February 14 | Company | Amazon cancels plans to open new HQ2 in New York City after massive backlash from local politicians and community members. Plans in Northern Virginia remain unchanged.[157] |

| 2019 | International | Having already invested over $6 billion in India, a key growth market, Amazon acquired a 49% stake in Future Coupons, a subsidiary of Future Retail, India's second largest retail chain after Reliance Industries. The deal would give Amazon a 3.58% stake in Future Retail through warrants owned by Future Coupons.[158] |

References

[edit]- ^ "Amazon Empire: The Rise and Reign of Jeff Bezos". PBS.

- ^ Kantar. "Accelerated Growth Sees Amazon Crowned 2019's BrandZ™ Top 100 Most Valuable Global Brand". www.prnewswire.com (Press release). Retrieved May 25, 2020.

- ^ Guevara, Natalie (November 17, 2020). "Amazon's John Schoettler has helped change how we think of corporate campuses". bizjournals.com. Archived from the original on March 9, 2021. Retrieved March 9, 2021.

- ^ Kakutani, Michiko (October 28, 2013). "Selling as Hard as He Can". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on October 29, 2013. Retrieved December 20, 2021.

- ^ "Person of the Year – Jeffrey P. Bezos". Time. December 27, 1999. Archived from the original on April 8, 2000. Retrieved January 5, 2008.

- ^ "Jeff Bezos: The King of e-Commerce". Entrepreneur.com. October 10, 2008. Retrieved August 23, 2017.

- ^ "AMAZON COM INC (Form: S-1, Received: 03/24/1997 00:00:00)". nasdaq.com. March 24, 1997. Retrieved July 15, 2014.

- ^ Amazon's Jeff Bezos: With Jeremy Clarkson, we're entering a new golden age of television Retrieved August 18, 2015.

- ^ a b c Byers, Ann (2006), Jeff Bezos: the founder of Amazon.com, The Rosen Publishing Group, pp. 46–47, ISBN 9781404207172

- ^ Murphy Jr., Bill (August 6, 2013). "'Follow the Money' and Other Lessons From Jeff Bezos".

- ^ "You Can Now Buy the House Where Jeff Bezos Started Amazon, If You Really Have to Or Something". Gizmodo. February 12, 2019.

- ^ "Amazon Company History". Retrieved May 6, 2013.

- ^ Spiro, Josh. "The Great Leaders Series: Jeff Bezos, Founder of Amazon.com". Inc.com. Retrieved February 7, 2013.

- ^ Neate, Rupert (June 22, 2014). "Amazon's Jeff Bezos: the man who wants you to buy everything from his company". The Guardian. Retrieved June 28, 2018.

- ^ Tom Metcalf (August 1, 2018). "A hidden Amazon fortune: Bezos' parents may be worth billions". Los Angeles Times.

- ^ "Jeff Bezos's Single Teen Mother Brought Him To School With Her As A Baby. They Couldn't Afford A Phone — Now She's Worth $30 Billion". Yahoo! Finance. Retrieved August 8, 2023.

- ^ "Amazon opens for business". HISTORY. Retrieved May 16, 2021.

- ^ "Amazon company timeline". Corporate IR. January 2015. Archived from the original on October 27, 2007.

- ^ Spiro, Josh. "The Great Leaders Series: Jeff Bezos, Founder of Amazon.com".

- ^ "World's Largest Bookseller Opens on the Web". URLwire. October 4, 1995. Archived from the original on January 16, 2013. Retrieved January 2, 2019.

- ^ "If You Invested in Amazon at Its IPO, You Could Have Been a Millionaire". Fortune. Retrieved July 13, 2018.

- ^ a b "Forming a Plan, The Company Is Launched, One Million Titles". Reference for Business: Encyclopedia of Business, 2nd ed. Retrieved September 1, 2012.

- ^ Packer, George (February 10, 2014). "Cheap Words". The New Yorker. Retrieved February 15, 2018.

- ^ Ramo, Joshua Cooper (December 27, 1999). "Jeffrey Preston Bezos: 1999 PERSON OF THE YEAR". Time. ISSN 0040-781X. Retrieved July 13, 2018.

- ^ "Amazon Logo and its History". Corporate IR.net. January 5, 2000.

- ^ Spector, Robert (2002). Amazon.com: Get Big Fast.

- ^ "Amazon posts first-ever profit in 4Q - Jan. 22, 2002".

- ^ "Amazon employs 1 out of 153 workers in America". shoppersinusa. Retrieved December 6, 2021.

- ^ Michael J. de la Merced; Nick Wingfield (June 16, 2017). "Amazon to Buy Whole Foods in $13.4 Billion Deal". The New York Times.

- ^ La Monica, Paul; Isidore, Chris (June 16, 2017). "Amazon is buying Whole Foods for $13.7 billion". CNN Money. CNNMoney. Retrieved June 16, 2017.

- ^ Merced, Michael (June 16, 2017). "Walmart to Buy Bonobos, Men's Wear Company, for $310 Million". The New York Times. Retrieved June 16, 2017.

- ^ "Whole Foods shareholders say yes to Amazon deal". KXAN.com. Associated Press. August 23, 2017. Archived from the original on August 24, 2017. Retrieved August 24, 2017.

- ^ Johnson, Alex (August 23, 2017). "Amazon's Acquisition of Whole Foods Won't Be Blocked by FTC". NBC News. Retrieved August 24, 2017.

- ^ Barron, Richard M. (September 8, 2017). "Triad to take regional approach to Amazon proposal". Winston-Salem Journal. Retrieved October 20, 2017.

- ^ Craver, Richard (October 19, 2017). "Triad woos Amazon in bid for second headquarters". Winston-Salem Journal. Retrieved October 20, 2017.

- ^ Craver, Richard (September 16, 2017). "Triad economic officials prepare to cast long-shot bid for second Amazon headquarters". Winston-Salem Journal. Retrieved October 20, 2017.

- ^ "Amazon donates space in headquarters to Seattle nonprofit | 790 KGMI". 790 KGMI. Retrieved May 12, 2017.

- ^ Yurieff, Kaya (February 2018). "Amazon: We hired 130,000 workers in 2017". CNN Tech.

- ^ Schlosser, Kurt (February 2018). "Amazon now employs 566,000 people worldwide — a 66 percent jump from a year ago". GeekWire.

- ^ Ovide, Shira (August 8, 2018). "Amazon Captures 5 Percent of American Retail Spending. Is That a Lot?". Bloomberg Businessweek. Retrieved August 9, 2018.

- ^ "Amazon Orders 20,000 Mercedes Vans to Bolster Delivery Program". Bloomberg.com. September 5, 2018. Retrieved September 6, 2018.

- ^ Stevens, Laura (September 5, 2018). "Amazon Orders 20,000 Mercedes-Benz Vans for New Delivery Service". Wall Street Journal. ISSN 0099-9660. Retrieved September 6, 2018.

- ^ Capoot, Ashley (November 14, 2022). "Amazon reportedly plans to lay off about 10,000 employees starting this week". CNBC. Retrieved November 14, 2022.

- ^ Thorbecke, Catherine (January 5, 2023). "Amazon will lay off more than 18,000 workers". CNN Business.

- ^ Hadero, Haleluya (March 20, 2023). "Amazon cuts 9,000 more jobs, bringing 2023 total to 27,000". Associated Press.

- ^ Dastin, Jeffrey (September 28, 2023). "Amazon steps up AI race with Anthropic investment". Reuters.

- ^ "Amazon and Anthropic announce strategic collaboration to advance generative AI". US About Amazon. September 25, 2023. Retrieved September 25, 2023.

- ^ Andrea Riviera (October 20, 2023). "Amazon, humanoid robot takes service in warehouses".

- ^ "Amazon tests humanoid robots in warehouses: "They will help humans, not replace them"". October 22, 2023.

- ^ "Amazon ERC Phone Number".

- ^ Taibbi, Matt (November 14, 2018). "Amazon's Long Game Is Clearer Than Ever". Rolling Stone. Retrieved January 3, 2019.

- ^ Stevens, Laura; Morris, Keiko; Honan, Katie (November 13, 2018). "Amazon Picks New York City, Northern Virginia for Its HQ2 Locations". The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved January 3, 2019.

- ^ Martz, Michael. "How Virginia sealed the deal on Amazon's HQ2, 'the biggest economic development project in U.S. history'". Richmond Times-Dispatch. Retrieved November 17, 2018.

- ^ Goodman, J. David (February 14, 2019). "Amazon Pulls Out of Planned New York City Headquarters". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved February 14, 2019.

- ^ Miranda, Mariah (February 15, 2019). "Virginia is now the sole winner of Amazon's HQ2. Here's what its planned neighborhood looks like right now". Business Insider. Retrieved March 17, 2020.

- ^ "Amazon fires worker who organized Staten Island warehouse walkout". www.cbsnews.com.

- ^ Smalls, Chris (April 2, 2020). "Dear Jeff Bezos, instead of firing me, protect your workers from coronavirus | Chris Smalls". The Guardian – via www.theguardian.com.

- ^ Brian Fung (March 29, 2020). "Amazon workers to stage a walkout Monday, demanding closure of Staten Island facility". CNN.

- ^ "Amazon warehouse workers walk out over coronavirus". www.cbsnews.com.

- ^ Dzieza, Josh (March 30, 2020). "Amazon warehouse workers walk out in rising tide of COVID-19 protests". The Verge.

- ^ but that didn't last for long. Amazon suspends shipments of non-essential products to warehouses amid coronavirus-driven shortages

- ^ a b Amazon lifts ban on shipping of non-essential products amid hiring spree

- ^ Spangler, Todd (May 17, 2021). "Amazon Said to Make $9 Billion Offer for MGM". Variety. Retrieved May 17, 2021.

- ^ Lang, Brent; Spangler, Todd (May 26, 2021). "Amazon Buys MGM, Studio Behind James Bond, for $8.45 Billion". Variety. Retrieved May 26, 2021.

- ^ "U.S. Antitrust enforcers won't challenge Amazon's MGM deal, dashing hopes of monopoly critics". Politico.

- ^ MacKrael, Kim (March 15, 2022). "Amazon Purchase of MGM Gets Green Light in EU". Wall Street Journal.

- ^ "Amazon Wins EU Approval for $8.45 Billion MGM Film Studio Purchase". Bloomberg.com. March 15, 2022.

- ^ Chee, Foo Yun (March 15, 2022). "Amazon wins EU antitrust nod for $8.5 BLN MGM deal". Reuters.

- ^ "Amazon's MGM Acquisition Cleared by European Union in Key Approval". March 15, 2022.

- ^ "Amazon's MGM Buy Approved by European Regulators". The Hollywood Reporter. March 15, 2022.

- ^ "Amazon's Buy of MGM Cleared in EU".

- ^ "Amazon wins EU approval for its $8.45 billion purchase of MGM".

- ^ "Amazon-MGM Town Hall Scheduled for Friday; Amazon's Mike Hopkins Presages Upcoming Mesh & MGM COO – Updated". March 17, 2022.

- ^ "Amazon's Mike Hopkins Stresses "Phased Approach to Integration Changes", Details Interim Reporting Structure in Memo to MGM Staff". March 18, 2022.

- ^ "MGM Shakeup: Mike de Luca & Pam Abdy Leaving as Studio Enters Amazon Fold; Read Exit Memos". April 27, 2022.

- ^ a b Day, Matt (January 22, 2018). "Amazon Go cashierless convenience store opens to the public in Seattle". Seattle Times. Retrieved June 4, 2018.

- ^ Weise, Elizabeth (January 21, 2018). "Amazon opens its grocery store without a checkout line to the public". USAToday. Retrieved June 4, 2018.

- ^ Silver, Curtis (December 5, 2016). "Amazon Announces No-Line Retail Shopping Experience With Amazon Go". Forbes. Retrieved December 5, 2016.

- ^ Heater, Brian (December 5, 2016). "Amazon launches a beta of Go, a cashier-free, app-based food shopping experience". TechCrunch. Retrieved December 6, 2016.

- ^ Garun, Natt (December 5, 2016). "Amazon just launched a cashier-free convenience store". The Verge. Retrieved June 4, 2018.

- ^ Leswing, Kif (December 5, 2016). "This is Amazon's grocery store of the future: No cashiers, no registers and no lines". Business Insider. Retrieved December 5, 2016.

- ^ Hardawar, Devindra (December 5, 2016). "Amazon Go is a grocery store with no checkout lines". Engadget. Retrieved December 5, 2016.

- ^ Say, My. "Amazon Go Is About Payments, Not Grocery". Forbes. Retrieved January 24, 2017.

- ^ Statt, Nick (October 23, 2018). "Amazon's latest cashier-less Go store opens in San Francisco today". The Verge. Retrieved November 2, 2018.

- ^ "Amazon's new retail store only stocks items rated 4 stars and up". Engadget. Retrieved September 27, 2018.

- ^ Thomas, Lauren (September 26, 2018). "Amazon is opening a new store that sells items from its website rated 4 stars and above". CNBC. Retrieved September 27, 2018.

- ^ "Amazon's new store only sells products with 4-star ratings and above". The Verge. Retrieved September 27, 2018.

- ^ Bourke, Joanna (November 10, 2021). "Amazon heads to Westfield London for next '4-star' UK general store". Evening Standard. Retrieved March 13, 2022.

- ^ Gartenberg, Chaim (March 2, 2022). "Amazon is closing all 68 of its Books, 4-Star, and Pop Up physical stores". The Verge. Vox Media. Retrieved March 13, 2022.

- ^ "Modi effect: Amazon to pour additional $3 billion into India, says Jeff Bezos". June 8, 2016.

- ^ "Amazon India Investments". Quartz. July 30, 2014.

- ^ Domainnamewire.com (September 14, 2014). "Wow: Amazon.com buys .Buy for $4.6 million, .Tech sells for $6.8 million".

- ^ ".Buy Domain Sold to Amazon.com for $4,588,888". Uttamujjwal. September 2014. Archived from the original on September 24, 2014. Retrieved September 18, 2014.

- ^ Olsen, Stefanie (July 14, 2008). "Amazon invests in Engine Yard's cloud computing". News.cnet.com. Retrieved August 4, 2011.

- ^ Isaac, Mike (December 2, 2010). "LivingSocial Receives $175 Million Investment From Amazon". Forbes. Retrieved September 6, 2012.

- ^ "Amazon and Google are in an epic battle to dominate the cloud—and Amazon may already have won – Quartz". Qz.com. April 16, 2014. Retrieved January 17, 2016.

- ^ a b c d e f g Stone, Brad (2013). The Everything Store: Jeff Bezos and the Age of Amazon. New York: Little Brown and Co. ISBN 9780316219266. OCLC 856249407.

- ^ "Amazon Media Room: Press Releases". Phx.corporate-ir.net. Retrieved January 17, 2016.

- ^ "Amazon.com Is Expanding Beyond Books". The New York Times. August 5, 1998. Retrieved January 10, 2016.

- ^ "Alibaba chief Jack Ma disappoints investors with London no-show". The Daily Telegraph. September 17, 2014. Retrieved January 17, 2016.

- ^ "Why Amazon Should Fear Alibaba". Forbes. Retrieved January 17, 2016.

- ^ "Amazon, Barnes&Noble settle patent suit – CNET". Cnet.com. Retrieved January 15, 2016.

- ^ "Amazon releases A9 search engine". Macworld.com. Retrieved January 17, 2016.

- ^ "2003 Amazon.com Annual Report" (PDF). AnnualReports.com. December 31, 2003. Retrieved February 5, 2020.

- ^ "Joyo Amazon was renamed to Amazon China" (in Chinese). NetEase. October 27, 2011. Retrieved October 27, 2011.

- ^ Barr, Jeff (August 25, 2006). "Amazon EC2 Beta". Amazon Web Services Blog. Retrieved May 31, 2013.

- ^ "Amazon.com Investor Relations: Press Release". Phx.corporate-ir.net. Retrieved January 17, 2016.

- ^ "Amazon to pay Toys R Us $51M to settle suit – ABC News". Abcnews.go.com. Retrieved January 15, 2016.

- ^ "CreateSpace: Self Publishing and Free Distribution for Books, CD, DVD". Retrieved January 15, 2016.

- ^ Harris, Craig; Cook, John (August 1, 2007). "Amazon starts grocery delivery service". Seattle Post-Intelligencer. Retrieved November 26, 2008.

- ^ "Amazon.com Launches Public Beta of Amazon MP3". BusinessWire (Press release). September 25, 2007. Archived from the original on January 2, 2013.

- ^ "Here's Why Amazon Bought Zappos". Mashable.com. July 22, 2009. Retrieved January 10, 2016.

- ^ Jeffrey A. Trachtenberg and Geoffrey A. Fowler (October 20, 2009). "B&N Reader Out Tuesday". The Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on October 21, 2009. Retrieved October 20, 2009.

- ^ "Apple introduces iBooks store for iPad". Appleinsider.com. Retrieved January 17, 2016.

- ^ "Amazon Says E-Books Now Top Hardcover Sales". The New York Times. July 19, 2010. Retrieved January 17, 2016.

- ^ Tim Bradshaw In London, Jonathan Birchall In New York (January 20, 2011). "Amazon acquires Lovefilm for £200m". Financial Times. Retrieved January 17, 2016.

- ^ "Borders Closing: Why the Bookstore Chain Failed". Ibtimes.com. July 22, 2011. Retrieved January 15, 2016.

- ^ Christina Warren (February 22, 2011). "HANDS ON: Amazon's Prime Instant Video". Mashable.com. Retrieved November 27, 2013.

- ^ "Amazon Media Room: Press Releases". corporate-ir.net.

- ^ Amazon.com (May 23, 2013). "Developers Can Now Distribute Apps in Nearly 200 Countries Worldwide on Amazon – Amazon Mobile App Distribution Blog". Developer.amazon.com. Retrieved November 27, 2013.

- ^ "California Becomes Seventh State to Adopt "Amazon" Tax on Out-of-State Online Sellers". Taxfoundation.org. July 2011. Retrieved January 17, 2016.

- ^ "Photos: A look at Amazon's new delivery locker at 7-Eleven – GeekWire". Geekwire.com. September 5, 2011. Retrieved January 15, 2016.

- ^ "Amazon Unveils $199 Kindle Fire Tablet, Taking on Apple IPad – Bloomberg Business". Bloomberg.com. September 28, 2011. Retrieved January 17, 2016.

- ^ "The Justice Department Just Made Jeff Bezos Dictator-for-Life – The Atlantic". Theatlantic.com. April 12, 2012. Retrieved January 15, 2016.

- ^ "Amazon Acquires Kiva Systems in Second-Biggest Takeover – Bloomberg Business". Bloomberg.com. March 19, 2012. Retrieved January 10, 2016.

- ^ "Documents: Amazon risking little in Texas sales tax deal". Statesman.com. Retrieved January 10, 2016.

- ^ "Kobo Announces Their New E-Readers". Wired.com. Retrieved January 17, 2016.

- ^ "Amazon Acquires Social Reading Site Goodreads, Which Gives The Company A Social Advantage Over Apple". TechCrunch. March 28, 2013. Retrieved March 29, 2013.

- ^ Srivas, Anuj (June 5, 2013). "Amazon now in India – The Hindu". Thehindu.com. Retrieved January 17, 2016.

- ^ "Amazon Invades India – Fortune". Fortune.com. Retrieved January 17, 2016.

- ^ "Amazon's Fire Phone to sell exclusively on AT&T for $199.98 starting July 25th". Theverge.com. June 18, 2014. Retrieved January 17, 2016.

- ^ "Amazon acquires Twitch: World's largest e-tailer buys largest gameplay-livestreaming site". Venturebeat.com. August 25, 2014. Retrieved January 17, 2016.

- ^ "Amazon Closes Multi-Year Deal With Simon & Schuster – Business Insider". Businessinsider.com. Retrieved January 15, 2016.

- ^ Stone, Brad; Soper, Spencer (November 6, 2014). "Amazon Unveils a Listening, Talking, Music-Playing Speaker for Your Home". Bloomberg Businessweek. Bloomberg L.P. Archived from the original on November 8, 2014. Retrieved November 7, 2014.

- ^ "Amazon Echo is now available for everyone to buy for $179.99, shipments start on July 14". Android Central. Archived from the original on December 8, 2015. Retrieved February 11, 2019.

- ^ "Amazon Unbundles Alexa Virtual Assistant From Echo With New Dev Tools". TechCrunch. AOL. June 25, 2015.

- ^ "Amazon and Hachette have finally resolved their bitter dispute". The Verge. November 13, 2014. Retrieved January 15, 2016.

- ^ "Alibaba $1 Billion Dollar Cloud Investment – International Competition Mounting »". Cloudtweaks.com. Retrieved January 17, 2016.

- ^ Dillet, Romain (August 26, 2015). "Amazon Underground Features An Android App Store Focused On "Actually Free" Apps". TechCrunch. Retrieved April 26, 2016.

- ^ Singleton, Micah (August 26, 2015). "Amazon launches Underground to promote free apps and games. The Free App of the Day program has also come to a close". The Verge. Retrieved April 26, 2016.

- ^ Barrett, Brian (August 29, 2015). "Has Amazon Cracked the Problem With In-App Payments?". Wired Magazine. Retrieved April 26, 2016.

- ^ Duryee, Tricia (September 8, 2015). "Amazon confirms Prime Now restaurant delivery launch in Seattle area, hints at broader rollout". GeekWire. Retrieved December 21, 2016.

- ^ Jennings, Lisa (September 8, 2015). "Amazon launches restaurant delivery in Seattle. Service is available to Amazon Prime Now customers only". Nation's Restaurant News. Retrieved December 21, 2016.

- ^ "Amazon is opening its first physical bookstore today". The Verge. November 2, 2015. Retrieved January 17, 2016.

- ^ Greene, Jay (December 14, 2015). "Workers move in to the first of Amazon's downtown towers". The Seattle Times. Retrieved January 17, 2016.

- ^ Reisinger, Don (December 14, 2016). "Watch Amazon's Prime Air Complete Its First Drone Delivery". Fortune Magazine. Retrieved December 21, 2016.

- ^ Fierberg, Emma (December 14, 2016). "Watch Amazon make its first drone delivery". Business Insider. Retrieved December 21, 2016.

- ^ "Amazon to Acquire Whole Foods for $13.7 Billion". Bloomberg.com. June 16, 2017. Retrieved June 19, 2017.

- ^ "Amazon HQ2". Amazon. Retrieved September 14, 2017.

- ^ "8 cities fit for Amazon's second headquarters". CNN. September 11, 2017. Retrieved September 14, 2017.

- ^ Wingfield, Nick (January 18, 2018). "Amazon Chooses 20 Finalists for Second Headquarters". The New York Times. Retrieved October 5, 2018.

- ^ "Amazon opens its grocery store without a checkout line to the public". USA Today. Retrieved October 5, 2018.

- ^ "Amazon launches in Turkey". Reuters. September 19, 2018. Retrieved September 19, 2018.

- ^ Isidore, Danielle Wiener-Bronner and Chris (October 2, 2018). "Amazon announces $15 minimum wage for all US employees". Retrieved October 5, 2018.

- ^ Partington, Richard (October 2, 2018). "Amazon raises minimum wage for US and UK employees". the Guardian. Retrieved October 5, 2018.

- ^ Yurieff, Kaya (November 13, 2018). "Amazon picks New York and Northern Virginia for HQ2". cnn.com. Retrieved October 5, 2018.

- ^ DePillis, Lydia; Sherman, Ivory. "Amazon's extraordinary evolution: A timeline". www.cnn.com. Retrieved March 7, 2019.

- ^ "Amazon is acquiring a 49% stake in India's Future Coupons". TechCrunch.