History of Albany, New York (1942–1983)

| History of Albany, New York |

|---|

|

|

|

The history of Albany, New York from 1942 to 1983 begins with the beginning of the tenure of Erastus Corning 2nd as mayor and ends with Corning's death in 1983.

History

[edit]Erastus Corning 2nd, arguably Albany's most notable mayor (and great-grandson of the former mayor of the same name), was elected in 1941.[1] Although he was the longest-serving mayor of any city in United States history (1942 until his death in 1983), one historian describes Corning's tenure as "long on years, short on accomplishments,"[2] citing Corning's preference for maintaining the status quo as a factor that held back potential progress during his tenure.[3] While Corning brought stability to the office of mayor, it is said that even those that idolize him cannot come up with a sizable list of "major concrete Corning achievements."[4] Corning is given credit for saving, albeit somewhat unintentionally, much of Albany's historic architecture.[Note 1]

During the 1950s and 1960s, a time when federal aid for urban renewal was plentiful,[3] Albany did not see much progress in either commerce or infrastructure. It lost more than 20 percent of its population during the Corning years, and most of the downtown businesses moved to the suburbs.[5] While cities across the country experienced similar issues, the problems were magnified in Albany: interference from the Democratic political machine hindered progress considerably.[3] Governor Nelson Rockefeller (1959–1973) (R), who had a preference for grandiose, monumental architecture and large, government-sponsored building projects, was the driving force behind the construction of the Empire State Plaza, SUNY Albany's uptown campus, and much of the W. Averell Harriman State Office Building Campus.[6] Albany County Republican Chairman Joseph C. Frangella once quipped, "Governor Rockefeller was the best mayor Albany ever had."[7] Corning, though opposed to the project, was responsible for negotiating the payment plan for the Empire State Plaza. Rockefeller did not want to be limited by the Legislature's power of the purse, so Corning devised a plan to have the county pay for the construction and have the state sign a lease-ownership agreement. The state would pay off the bonds until 2004. It was Rockefeller's only viable option, and he agreed. Due to the clout Corning gained from the situation, he was able to get the State Museum, a convention center, and a restaurant, back in the plans—ideas that Rockefeller had originally vetoed. The county gained $35 million in fees and the city received $13 million for lost tax revenue.[8]

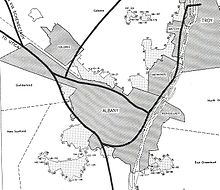

Another major project of the 1960s and 1970s was Interstate 787 and the South Mall Arterial.[Note 2] Construction began in the early 1960s. One of the project's main consequences was separating the city from the Hudson River. Corning is sometimes called shortsighted with respect to use of the waterfront, as he could have used his influence to change the location of I-787, which now cuts the city off from "its whole raison d'être".[9] Much of the original plan never came to fruition, however: Rockefeller had wanted the South Mall Arterial to pass through the Empire State Plaza. The project would have required an underground trumpet interchange below Washington Park, connecting to the (eventually cancelled) Mid-Crosstown Arterial.[10] To this day, evidence of the original plan is still visible.[Note 3] In 1967 the hamlet of Karlsfeld became the last annexation to be added to the city limits, having come from Bethlehem.[11]

Notes

[edit]- ^ Grondahl summarizes it as, "This hard-line position of isolationism on the part of the machine was a curse economically – but a strange blessing unintentionally in architectural terms. While downtown went to seed and plans for large-scale construction and improvements came to a virtual standstill in Albany without federal money, pockets of the city's historic housing stock escaped the wrecking ball."[3]

- ^ The Empire State Plaza was originally known as the South Mall; the South Mall Arterial is the only remnant of that naming scheme.

- ^ For example, the Plaza has four traffic tunnels, two intended for through traffic, and two for local traffic (only the outer, local traffic tunnels are in use); the Arterial ends abruptly between Jay Street and Hudson Avenue just west of South Swan Street (42°39′6.17″N 73°45′43.54″W / 42.6517139°N 73.7620944°W); the east end of the Dunn Memorial Bridge ends abruptly in Rensselaer (42°38′33.33″N 73°44′44.78″W / 42.6425917°N 73.7457722°W); and Henry Johnson Boulevard, which would have extended as part of the Mid-Crosstown Arterial, ends abruptly at Livingston Avenue (42°39′49.92″N 73°45′30.58″W / 42.6638667°N 73.7584944°W).

References

[edit]- ^ McEneny (2006), p. 157

- ^ Grondahl (2007), p. 490

- ^ a b c d Grondahl (2007), p. 500

- ^ Grondahl (2007), p. 494

- ^ Grondahl (2007), p. 492

- ^ Grondahl (2007), p. 501

- ^ Grondahl (2007), p. 502

- ^ Grondahl (2007), pp. 467–469

- ^ Grondahl (2007), p. 498

- ^ Jordan, Christopher. Capital Highways. Mid-Crosstown Arterial; 2006 [archived 2011-04-29; Retrieved 2010-06-28].

- ^ Albany County, New York. Appendix [archived 2008-08-23; Retrieved 2010-09-11].

Bibliography

[edit]- Grondahl, Paul. Mayor Erastus Corning: Albany Icon, Albany Enigma. Albany: State University of New York Press; 2007. ISBN 978-0-7914-7294-1.

- Lemak, Jennifer A.. Albany, New York and the Great Migration. Afro-Americans in New York Life and History. 2008;32(1):47–74.

- Lemak, Jennifer A.. Southern Life, Northern City: The History of Albany's Rapp Road Community. SUNY Press; 2008.

- McEneny, John. Albany, Capital City on the Hudson: An Illustrated History. Sun Valley, California: American Historical Press; 2006. ISBN 1-892724-53-7.