Hiragana

| Hiragana 平仮名 ひらがな | |

|---|---|

| |

| Script type | |

Time period | ~800 CE to the present |

| Direction | Vertical right-to-left, left-to-right |

| Languages | Japanese, Hachijō and the Ryukyuan languages |

| Related scripts | |

Parent systems | |

Sister systems | Katakana, Hentaigana |

| ISO 15924 | |

| ISO 15924 | Hira (410), Hiragana |

| Unicode | |

Unicode alias | Hiragana |

| |

|

| Japanese writing |

|---|

| Components |

| Uses |

| Transliteration |

Hiragana (平仮名, ひらがな, IPA: [çiɾaɡaꜜna, çiɾaɡana(ꜜ)]) is a Japanese syllabary, part of the Japanese writing system, along with katakana as well as kanji.

It is a phonetic lettering system. The word hiragana means "common" or "plain" kana (originally also "easy", as contrasted with kanji).[1][2][3]

Hiragana and katakana are both kana systems. With few exceptions, each mora in the Japanese language is represented by one character (or one digraph) in each system. This may be a vowel such as /a/ (hiragana あ); a consonant followed by a vowel such as /ka/ (か); or /N/ (ん), a nasal sonorant which, depending on the context and dialect, sounds either like English m, n or ng ([ŋ]) when syllable-final or like the nasal vowels of French, Portuguese or Polish.[citation needed][contradictory] Because the characters of the kana do not represent single consonants (except in the case of the aforementioned ん), the kana are referred to as syllabic symbols and not alphabetic letters.[4]

Hiragana is used to write okurigana (kana suffixes following a kanji root, for example to inflect verbs and adjectives), various grammatical and function words including particles, and miscellaneous other native words for which there are no kanji or whose kanji form is obscure or too formal for the writing purpose.[5] Words that do have common kanji renditions may also sometimes be written instead in hiragana, according to an individual author's preference, for example to impart an informal feel. Hiragana is also used to write furigana, a reading aid that shows the pronunciation of kanji characters.

There are two main systems of ordering hiragana: the old-fashioned iroha ordering and the more prevalent gojūon ordering.

Writing system

[edit]

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Only used in some proper names | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

After the 1900 script reform, which deemed hundreds of characters hentaigana, the hiragana syllabary consists of 48 base characters, of which two (ゐ and ゑ) are only used in some proper names:

- 5 singular vowels: あ /a/, い /i/, う /u/, え /e/, お /o/ (respectively pronounced [a], [i], [ɯ], [e] and [o])

- 42 consonant–vowel unions: for example き /ki/, て /te/, ほ /ho/, ゆ /ju/, わ /wa/ (respectively pronounced [ki], [te], [ho], [jɯ] and [wa])

- 1 singular consonant (ん), romanized as n.

These are conceived as a 5×10 grid (gojūon, 五十音, "Fifty Sounds"), as illustrated in the adjacent table, read あ (a), い (i), う (u), え (e), お (o), か (ka), き (ki), く (ku), け (ke), こ (ko) and so forth (but si→shi, ti→chi, tu→tsu, hu→fu, wi→i, we→e, wo→o). Of the 50 theoretically possible combinations, yi, ye, and wu are completely unused. On the w row, ゐ and ゑ, pronounced [i] and [e] respectively, are uncommon in modern Japanese, while を, pronounced [o], is common as a particle but otherwise rare. Strictly speaking, the singular consonant ん (n) is considered as outside the gojūon.

These basic characters can be modified in various ways. By adding a dakuten marker ( ゛), a voiceless consonant is turned into a voiced consonant: k→g, ts/s→z, t→d, h/f→b and ch/sh→j (also u→v(u)). For example, か (ka) becomes が (ga). Hiragana beginning with an h (or f) sound can also add a handakuten marker ( ゜) changing the h (f) to a p. For example, は (ha) becomes ぱ (pa).

A small version of the hiragana for ya, yu, or yo (ゃ, ゅ or ょ respectively) may be added to hiragana ending in i. This changes the i vowel sound to a glide (palatalization) to a, u or o. For example, き (ki) plus ゃ (small ya) becomes きゃ (kya). Addition of the small y kana is called yōon.

A small tsu っ, called a sokuon, indicates that the following consonant is geminated (doubled). In Japanese this is an important distinction in pronunciation; for example, compare さか, saka, "hill" with さっか, sakka, "author". However, it cannot be used to double an n – for this purpose, the singular n (ん) is added in front of the syllable, as in みんな (minna, "all"). The sokuon also sometimes appears at the end of utterances, where it denotes a glottal stop, as in いてっ! ([iteʔ], "Ouch!").

Two hiragana have pronunciations that depend on the context:

- は is pronounced [wa] when used as a particle (otherwise, [ha]).

- へ is pronounced [e] when used as a particle (otherwise, [he]).

Hiragana usually spells long vowels with the addition of a second vowel kana; for example, おかあさん (o-ka-a-sa-n, "mother"). The chōonpu (long vowel mark) (ー) used in katakana is rarely used with hiragana, for example in the word らーめん, rāmen, but this usage is considered non-standard in Japanese. However, the Okinawan language uses chōonpu with hiragana. In informal writing, small versions of the five vowel kana are sometimes used to represent trailing off sounds (はぁ, haa, ねぇ, nee). Plain (clear) and voiced iteration marks are written in hiragana as ゝ and ゞ, respectively. These marks are rarely used nowadays.

Table of hiragana

[edit]The following table shows the complete hiragana together with the modified Hepburn romanization and IPA transcription, arranged in four categories, each of them displayed in the gojūon order.[7][8][9][10] Those whose romanization are in bold do not use the initial consonant for that row. For all syllables besides ん, the pronunciation indicated is for word-initial syllables; for mid-word pronunciations see below.

| Monographs (gojūon) | Digraphs (yōon) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| a | i | u | e | o | ya | yu | yo | |

| ∅ | あ a [a] |

い i [i] |

う u [ɯ] |

え e [e] |

お o [o] |

|||

| K | か ka [ka] |

き ki [ki] |

く ku [kɯ] |

け ke [ke] |

こ ko [ko] |

きゃ kya [kʲa] |

きゅ kyu [kʲɯ] |

きょ kyo [kʲo] |

| S | さ sa [sa] |

し shi [ɕi] |

す su [sɯ] |

せ se [se] |

そ so [so] |

しゃ sha [ɕa] |

しゅ shu [ɕɯ] |

しょ sho [ɕo] |

| T | た ta [ta] |

ち chi [tɕi] |

つ tsu [tsɯ] |

て te [te] |

と to [to] |

ちゃ cha [tɕa] |

ちゅ chu [tɕɯ] |

ちょ cho [tɕo] |

| N | な na [na] |

に ni [ɲi] |

ぬ nu [nɯ] |

ね ne [ne] |

の no [no] |

にゃ nya [ɲa] |

にゅ nyu [ɲɯ] |

にょ nyo [ɲo] |

| H | は ha [ha] (wa [wa] as particle) |

ひ hi [çi] |

ふ fu [ɸɯ] |

へ he [he] (e [e] as particle) |

ほ ho [ho] |

ひゃ hya [ça] |

ひゅ hyu [çɯ] |

ひょ hyo [ço] |

| M | ま ma [ma] |

み mi [mi] |

む mu [mɯ] |

め me [me] |

も mo [mo] |

みゃ mya [mʲa] |

みゅ myu [mʲɯ] |

みょ myo [mʲo] |

| Y | や ya [ja] |

[6] | ゆ yu [jɯ] |

𛀁[6] e [e] |

よ yo [jo] |

|||

| R | ら ra [ɾa] |

り ri [ɾi] |

る ru [ɾɯ] |

れ re [ɾe] |

ろ ro [ɾo] |

りゃ rya [ɾʲa] |

りゅ ryu [ɾʲɯ] |

りょ ryo [ɾʲo] |

| W | わ wa [wa] |

ゐ[6] i [i] |

[6] | ゑ[6] e [e] |

を o[a] [o] |

|||

| Monographs (gojūon) with diacritics (dakuten, handakuten) | Digraphs (yōon) with diacritics (dakuten, handakuten) | |||||||

| a | i | u | e | o | ya | yu | yo | |

| G | が ga [ɡa] |

ぎ gi [ɡi] |

ぐ gu [ɡɯ] |

げ ge [ɡe] |

ご go [ɡo] |

ぎゃ gya [ɡʲa] |

ぎゅ gyu [ɡʲɯ] |

ぎょ gyo [ɡʲo] |

| Z | ざ za [(d)za] |

じ ji [(d)ʑi] |

ず zu [(d)zɯ] |

ぜ ze [(d)ze] |

ぞ zo [(d)zo] |

じゃ ja [(d)ʑa] |

じゅ ju [(d)ʑɯ] |

じょ jo [(d)ʑo] |

| D | だ da [da] |

ぢ ji [(d)ʑi] |

づ zu [(d)zɯ] |

で de [de] |

ど do [do] |

ぢゃ ja [(d)ʑa] |

ぢゅ ju [(d)ʑɯ] |

ぢょ jo [(d)ʑo] |

| B | ば ba [ba] |

び bi [bi] |

ぶ bu [bɯ] |

べ be [be] |

ぼ bo [bo] |

びゃ bya [bʲa] |

びゅ byu [bʲɯ] |

びょ byo [bʲo] |

| P | ぱ pa [pa] |

ぴ pi [pi] |

ぷ pu [pɯ] |

ぺ pe [pe] |

ぽ po [po] |

ぴゃ pya [pʲa] |

ぴゅ pyu [pʲɯ] |

ぴょ pyo [pʲo] |

| Final nasal monograph (hatsuon) | Polysyllabic monographs (obsolete) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | kashiko | koto | sama | nari | mairasesoro | yori |

| ん n [m n ɲ ŋ ɴ ɰ̃] |

kashiko [kaɕiko] |

koto [koto] |

sama [sama] |

nari [naɾi] |

mairasesoro [maiɾasesoːɾoː] |

ゟ yori [joɾi] |

goto [goto] |

||||||

| Functional graphemes | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| sokuonfu | chōonpu | odoriji (monosyllable) | odoriji (polysyllable) |

| っ (indicates a geminate consonant) |

ー (indicates a long vowel) |

ゝ (reduplicates and unvoices syllable) |

〱 (reduplicates and unvoices syllable) |

| ゞ (reduplicates and voices syllable) |

〱゙ (reduplicates and voices syllable) | ||

| ゝ゚ (reduplicates and moves a h- or b-row syllable to the p-row) |

〱゚ (reduplicates and moves a h- or b-row syllable to the p-row) | ||

Spelling–phonology correspondence

[edit]In the middle of words, the g sound (normally [ɡ]) may turn into a velar nasal [ŋ] or velar fricative [ɣ]. For example, かぎ (kagi, key) is often pronounced [kaŋi]. However, じゅうご (jūgo, fifteen) is pronounced as if it was jū and go stacked end to end: [d͡ʑɯːɡo].[11]

In many accents, the j and z sounds are pronounced as affricates ([d͡ʑ] and [d͡z], respectively) at the beginning of utterances and fricatives [ʑ, z] in the middle of words. For example, すうじ sūji [sɯːʑi] 'number', ざっし zasshi [d͡zaɕɕi] 'magazine'.

The singular n is pronounced [m] before m, b and p, [n] before t, ch, ts, n, r, z, j and d, [ŋ] before k and g, [ɴ] at the end of utterances, and some kind of high nasal vowel [ɰ̃] before vowels, palatal approximants (y), and fricative consonants (s, sh, h, f and w).[citation needed]

In kanji readings, the diphthongs ou and ei are usually pronounced [oː] (long o) and [eː] (long e) respectively. For example, とうきょう (lit. toukyou) is pronounced [toːkʲoː] 'Tokyo', and せんせい sensei is [seɯ̃seː] 'teacher'. However, とう tou is pronounced [toɯ] 'to inquire', because the o and u are considered distinct, u being the verb ending in the dictionary form. Similarly, している shite iru is pronounced [ɕiteiɾɯ] 'is doing'.

In archaic forms of Japanese, there existed the kwa (くゎ [kʷa]) and gwa (ぐゎ [ɡʷa]) digraphs. In modern Japanese, these phonemes have been phased out of usage.

For a more thorough discussion on the sounds of Japanese, please refer to Japanese phonology.

Spelling rules

[edit]With a few exceptions, such as for the three particles は (pronounced [wa] instead of [ha]), へ (pronounced [e] instead of [he]) and [o] (written を instead of お), Japanese when written in kana is phonemically orthographic, i.e. there is a one-to-one correspondence between kana characters and sounds, leaving only words' pitch accent unrepresented. This has not always been the case: a previous system of spelling, now referred to as historical kana usage, differed substantially from pronunciation; the three above-mentioned exceptions in modern usage are the legacy of that system.

There are two hiragana pronounced ji (じ and ぢ) and two hiragana pronounced zu (ず and づ), but to distinguish them, particularly when typing Japanese, sometimes ぢ is written as di and づ is written as du. These pairs are not interchangeable. Usually, ji is written as じ and zu is written as ず. There are some exceptions. If the first two syllables of a word consist of one syllable without a dakuten and the same syllable with a dakuten, the same hiragana is used to write the sounds. For example, chijimeru ('to boil down' or 'to shrink') is spelled ちぢめる and tsuzuku ('to continue') is つづく.

For compound words where the dakuten reflects rendaku voicing, the original hiragana is used. For example, chi (血 'blood') is spelled ち in plain hiragana. When 鼻 hana ('nose') and 血 chi ('blood') combine to make hanaji (鼻血 'nose bleed'), the sound of 血 changes from chi to ji. So hanaji is spelled はなぢ. Similarly, tsukau (使う/遣う; 'to use') is spelled つかう in hiragana, so kanazukai (仮名遣い; 'kana use', or 'kana orthography') is spelled かなづかい in hiragana. However, there are cases where ぢ and づ are not used, such as the word for 'lightning', inazuma (稲妻). The first component, 稲, meaning 'rice plant', is written いな (ina). The second component, 妻 (etymologically 夫), meaning 'spouse', is pronounced つま (tsuma) when standalone or often as づま (zuma) when following another syllable, such in 人妻 (hitozuma, 'married woman'). Even though these components of 稲妻 are etymologically linked to 'lightning', it is generally arduous for a contemporary speaker to consciously perceive inazuma as separable into two discrete words. Thus, the default spelling いなずま is used instead of いなづま. Other examples include kizuna (きずな) and sakazuki (さかずき). Although these rules were officially established by a Cabinet Notice in 1986 revising the modern kana usage, they have sometimes faced criticism due to their perceived arbitrariness.

Officially, ぢ and づ do not occur word-initially pursuant to modern spelling rules. There were words such as ぢばん jiban 'ground' in the historical kana usage, but they were unified under じ in the modern kana usage in 1946, so today it is spelled exclusively じばん. However, づら zura 'wig' (from かつら katsura) and づけ zuke (a sushi term for lean tuna soaked in soy sauce) are examples of word-initial づ today.

No standard Japanese words begin with the kana ん (n). This is the basis of the word game shiritori. ん n is normally treated as its own syllable and is separate from the other n-based kana (na, ni etc.).

ん is sometimes directly followed by a vowel (a, i, u, e or o) or a palatal approximant (ya, yu or yo). These are clearly distinct from the na, ni etc. syllables, and there are minimal pairs such as きんえん kin'en 'smoking forbidden', きねん kinen 'commemoration', きんねん kinnen 'recent years'. In Hepburn romanization, they are distinguished with an apostrophe, but not all romanization methods make the distinction. For example, past prime minister Junichiro Koizumi's first name is actually じゅんいちろう Jun'ichirō pronounced [dʑɯɰ̃itɕiɾoː]

There are a few hiragana that are rarely used. Outside of Okinawan orthography, ゐ wi [i] and ゑ we [e] are only used in some proper names. 𛀁 e was an alternate version of え e before spelling reform, and was briefly reused for ye during initial spelling reforms, but is now completely obsolete. ゔ vu is a modern addition used to represent the /v/ sound in foreign languages such as English, but since Japanese from a phonological standpoint does not have a /v/ sound, it is pronounced as /b/ and mostly serves as a more accurate indicator of a word's pronunciation in its original language. However, it is rarely seen because loanwords and transliterated words are usually written in katakana, where the corresponding character would be written as ヴ. The digraphs ぢゃ, ぢゅ, ぢょ for ja/ju/jo are theoretically possible in rendaku, but are nearly never used in modern kana usage; for example, the word 夫婦茶碗, meoto-jawan (couple bowls), spelled めおとぢゃわん, where 茶碗 alone is spelled ちゃわん (chawan).

The みゅ myu kana is extremely rare in originally Japanese words; linguist Haruhiko Kindaichi raises the example of the Japanese family name Omamyūda (小豆生田) and claims it is the only occurrence amongst pure Japanese words. Its katakana counterpart is used in many loanwords, however.

Obsolete kana

[edit]Hentaigana

[edit]Polysyllabic kana

[edit]e and i

[edit]On the row beginning with わ /wa/, the hiragana ゐ /wi/ and ゑ /we/ are both quasi-obsolete, only used in some names. They are usually respectively pronounced [i] and [e]. In modified Hepburn romanization, they are generally written i and e.[9]

yi, ye and wu

[edit]yi

[edit]It has not been demonstrated whether the mora /ji/ existed in old Japanese. Though ye did appear in some textbooks during the Meiji period along with another kana for yi in the form of cursive 以. Today it is considered a Hentaigana by scholars and is encoded in Unicode 10[12] (𛀆) [13][14] This kana could have a colloquial use, to convert the combo yui (ゆい) into yii (𛀆い), due to other Japanese words having a similar change.[15]

ye

[edit]An early, now obsolete, hiragana-esque form of ye may have existed (𛀁 [je][16]) in pre-Classical Japanese (prior to the advent of kana), but is generally represented for purposes of reconstruction by the kanji 江, and its hiragana form is not present in any known orthography. In modern orthography, ye can also be written as いぇ (イェ in katakana).

| 衣 | 江 | |

|---|---|---|

| Hiragana | え | 𛀁 |

| Katakana | 𛀀 | エ |

While hiragana and katakana letters for "ye" were used for a short period after the advent of kana, the distinction between /ye/ and /e/ disappeared before glyphs could become established.

wu

[edit]It has not been demonstrated whether the mora /wu/ existed in old Japanese. However, hiragana wu also appeared in different Meiji-era textbooks (![]() ).[17][18] Although there are several possible source kanji, it is likely to have been derived from a cursive form of the man'yōgana 汙, although a related variant sometimes listed (

).[17][18] Although there are several possible source kanji, it is likely to have been derived from a cursive form of the man'yōgana 汙, although a related variant sometimes listed (![]() ) is from a cursive form of 紆.[19] However, it was never commonly used.[20] This character is included in Unicode 14 as HIRAGANA LETTER ARCHAIC WU (𛄟).[15]

) is from a cursive form of 紆.[19] However, it was never commonly used.[20] This character is included in Unicode 14 as HIRAGANA LETTER ARCHAIC WU (𛄟).[15]

History

[edit]

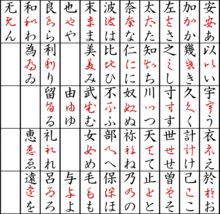

Hiragana developed from man'yōgana, Chinese characters used for their pronunciations, a practice that started in the 5th century.[21] The oldest examples of Man'yōgana include the Inariyama Sword, an iron sword excavated at the Inariyama Kofun. This sword is thought to be made in the year 辛亥年 (most commonly taken to be C.E. 471).[22] The forms of the hiragana originate from the cursive script style of Chinese calligraphy. The table to the right shows the derivation of hiragana from manyōgana via cursive script. The upper part shows the character in the regular script form, the center character in red shows the cursive script form of the character, and the bottom shows the equivalent hiragana. The cursive script forms are not strictly confined to those in the illustration.

When it was first developed, hiragana was not accepted by everyone. The educated or elites preferred to use only the kanji system. Historically, in Japan, the regular script (kaisho) form of the characters was used by men and called otokode (男手), "men's writing", while the cursive script (sōsho) form of the kanji was used by women. Hence hiragana first gained popularity among women, who were generally not allowed access to the same levels of education as men, thus hiragana was first widely used among court women in the writing of personal communications and literature.[23] From this comes the alternative name of onnade (女手) "women's writing".[24] For example, The Tale of Genji and other early novels by female authors used hiragana extensively or exclusively. Even today, hiragana is felt to have a feminine quality.[25]

Male authors came to write literature using hiragana. Hiragana was used for unofficial writing such as personal letters, while katakana and kanji were used for official documents. In modern times, the usage of hiragana has become mixed with katakana writing. Katakana is now relegated to special uses such as recently borrowed words (i.e., since the 19th century), names in transliteration, the names of animals, in telegrams, and for emphasis.

Originally, for all syllables there was more than one possible hiragana. In 1900, the system was simplified so each syllable had only one hiragana. The deprecated hiragana are now known as hentaigana (変体仮名).

The pangram poem Iroha-uta ("ABC song/poem"), which dates to the 10th century, uses every hiragana once (except n ん, which was just a variant of む before the Muromachi era).

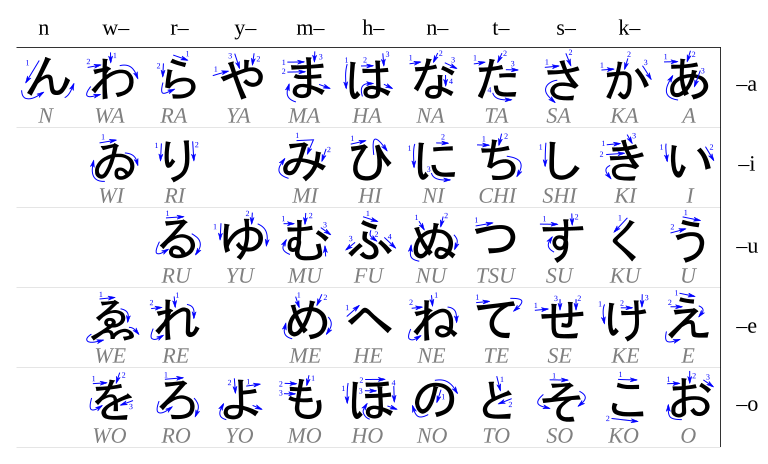

Stroke order and direction

[edit]The following table shows the method for writing each hiragana character. The table is arranged in a traditional manner, beginning top right and reading columns down. The numbers and arrows indicate the stroke order and direction respectively.

Unicode

[edit]Hiragana was added to the Unicode Standard in October, 1991 with the release of version 1.0.

The Unicode block for Hiragana is U+3040–U+309F:

| Hiragana[1][2] Official Unicode Consortium code chart (PDF) | ||||||||||||||||

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | A | B | C | D | E | F | |

| U+304x | ぁ | あ | ぃ | い | ぅ | う | ぇ | え | ぉ | お | か | が | き | ぎ | く | |

| U+305x | ぐ | け | げ | こ | ご | さ | ざ | し | じ | す | ず | せ | ぜ | そ | ぞ | た |

| U+306x | だ | ち | ぢ | っ | つ | づ | て | で | と | ど | な | に | ぬ | ね | の | は |

| U+307x | ば | ぱ | ひ | び | ぴ | ふ | ぶ | ぷ | へ | べ | ぺ | ほ | ぼ | ぽ | ま | み |

| U+308x | む | め | も | ゃ | や | ゅ | ゆ | ょ | よ | ら | り | る | れ | ろ | ゎ | わ |

| U+309x | ゐ | ゑ | を | ん | ゔ | ゕ | ゖ | ゙ | ゚ | ゛ | ゜ | ゝ | ゞ | ゟ | ||

| Notes | ||||||||||||||||

The Unicode hiragana block contains precomposed characters for all hiragana in the modern set, including small vowels and yōon kana for compound syllables as well as the rare ゐ wi and ゑ we; the archaic 𛀁 ye is included in plane 1 at U+1B001 (see below). All combinations of hiragana with dakuten and handakuten used in modern Japanese are available as precomposed characters (including the rare ゔ vu), and can also be produced by using a base hiragana followed by the combining dakuten and handakuten characters (U+3099 and U+309A, respectively). This method is used to add the diacritics to kana that are not normally used with them, for example applying the dakuten to a pure vowel or the handakuten to a kana not in the h-group.

Characters U+3095 and U+3096 are small か (ka) and small け (ke), respectively. U+309F is a ligature of より (yori) occasionally used in vertical text. U+309B and U+309C are spacing (non-combining) equivalents to the combining dakuten and handakuten characters, respectively.

Historic and variant forms of Japanese kana characters were first added to the Unicode Standard in October, 2010 with the release of version 6.0, with significantly more added in 2017 as part of Unicode 10.

The Unicode block for Kana Supplement is U+1B000–U+1B0FF, and is immediately followed by the Kana Extended-A block (U+1B100–U+1B12F). These blocks include mainly hentaigana (historic or variant hiragana):

| Kana Supplement[1] Official Unicode Consortium code chart (PDF) | ||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | A | B | C | D | E | F | |

| U+1B00x | 𛀀 | 𛀁 | 𛀂 | 𛀃 | 𛀄 | 𛀅 | 𛀆 | 𛀇 | 𛀈 | 𛀉 | 𛀊 | 𛀋 | 𛀌 | 𛀍 | 𛀎 | 𛀏 |

| U+1B01x | 𛀐 | 𛀑 | 𛀒 | 𛀓 | 𛀔 | 𛀕 | 𛀖 | 𛀗 | 𛀘 | 𛀙 | 𛀚 | 𛀛 | 𛀜 | 𛀝 | 𛀞 | 𛀟 |

| U+1B02x | 𛀠 | 𛀡 | 𛀢 | 𛀣 | 𛀤 | 𛀥 | 𛀦 | 𛀧 | 𛀨 | 𛀩 | 𛀪 | 𛀫 | 𛀬 | 𛀭 | 𛀮 | 𛀯 |

| U+1B03x | 𛀰 | 𛀱 | 𛀲 | 𛀳 | 𛀴 | 𛀵 | 𛀶 | 𛀷 | 𛀸 | 𛀹 | 𛀺 | 𛀻 | 𛀼 | 𛀽 | 𛀾 | 𛀿 |

| U+1B04x | 𛁀 | 𛁁 | 𛁂 | 𛁃 | 𛁄 | 𛁅 | 𛁆 | 𛁇 | 𛁈 | 𛁉 | 𛁊 | 𛁋 | 𛁌 | 𛁍 | 𛁎 | 𛁏 |

| U+1B05x | 𛁐 | 𛁑 | 𛁒 | 𛁓 | 𛁔 | 𛁕 | 𛁖 | 𛁗 | 𛁘 | 𛁙 | 𛁚 | 𛁛 | 𛁜 | 𛁝 | 𛁞 | 𛁟 |

| U+1B06x | 𛁠 | 𛁡 | 𛁢 | 𛁣 | 𛁤 | 𛁥 | 𛁦 | 𛁧 | 𛁨 | 𛁩 | 𛁪 | 𛁫 | 𛁬 | 𛁭 | 𛁮 | 𛁯 |

| U+1B07x | 𛁰 | 𛁱 | 𛁲 | 𛁳 | 𛁴 | 𛁵 | 𛁶 | 𛁷 | 𛁸 | 𛁹 | 𛁺 | 𛁻 | 𛁼 | 𛁽 | 𛁾 | 𛁿 |

| U+1B08x | 𛂀 | 𛂁 | 𛂂 | 𛂃 | 𛂄 | 𛂅 | 𛂆 | 𛂇 | 𛂈 | 𛂉 | 𛂊 | 𛂋 | 𛂌 | 𛂍 | 𛂎 | 𛂏 |

| U+1B09x | 𛂐 | 𛂑 | 𛂒 | 𛂓 | 𛂔 | 𛂕 | 𛂖 | 𛂗 | 𛂘 | 𛂙 | 𛂚 | 𛂛 | 𛂜 | 𛂝 | 𛂞 | 𛂟 |

| U+1B0Ax | 𛂠 | 𛂡 | 𛂢 | 𛂣 | 𛂤 | 𛂥 | 𛂦 | 𛂧 | 𛂨 | 𛂩 | 𛂪 | 𛂫 | 𛂬 | 𛂭 | 𛂮 | 𛂯 |

| U+1B0Bx | 𛂰 | 𛂱 | 𛂲 | 𛂳 | 𛂴 | 𛂵 | 𛂶 | 𛂷 | 𛂸 | 𛂹 | 𛂺 | 𛂻 | 𛂼 | 𛂽 | 𛂾 | 𛂿 |

| U+1B0Cx | 𛃀 | 𛃁 | 𛃂 | 𛃃 | 𛃄 | 𛃅 | 𛃆 | 𛃇 | 𛃈 | 𛃉 | 𛃊 | 𛃋 | 𛃌 | 𛃍 | 𛃎 | 𛃏 |

| U+1B0Dx | 𛃐 | 𛃑 | 𛃒 | 𛃓 | 𛃔 | 𛃕 | 𛃖 | 𛃗 | 𛃘 | 𛃙 | 𛃚 | 𛃛 | 𛃜 | 𛃝 | 𛃞 | 𛃟 |

| U+1B0Ex | 𛃠 | 𛃡 | 𛃢 | 𛃣 | 𛃤 | 𛃥 | 𛃦 | 𛃧 | 𛃨 | 𛃩 | 𛃪 | 𛃫 | 𛃬 | 𛃭 | 𛃮 | 𛃯 |

| U+1B0Fx | 𛃰 | 𛃱 | 𛃲 | 𛃳 | 𛃴 | 𛃵 | 𛃶 | 𛃷 | 𛃸 | 𛃹 | 𛃺 | 𛃻 | 𛃼 | 𛃽 | 𛃾 | 𛃿 |

Notes

| ||||||||||||||||

| Kana Extended-A[1][2] Official Unicode Consortium code chart (PDF) | ||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | A | B | C | D | E | F | |

| U+1B10x | 𛄀 | 𛄁 | 𛄂 | 𛄃 | 𛄄 | 𛄅 | 𛄆 | 𛄇 | 𛄈 | 𛄉 | 𛄊 | 𛄋 | 𛄌 | 𛄍 | 𛄎 | 𛄏 |

| U+1B11x | 𛄐 | 𛄑 | 𛄒 | 𛄓 | 𛄔 | 𛄕 | 𛄖 | 𛄗 | 𛄘 | 𛄙 | 𛄚 | 𛄛 | 𛄜 | 𛄝 | 𛄞 | 𛄟 |

| U+1B12x | 𛄠 | 𛄡 | 𛄢 | |||||||||||||

| Notes | ||||||||||||||||

The Unicode block for Kana Extended-B is U+1AFF0–U+1AFFF:

| Kana Extended-B[1][2] Official Unicode Consortium code chart (PDF) | ||||||||||||||||

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | A | B | C | D | E | F | |

| U+1AFFx | 𚿰 | 𚿱 | 𚿲 | 𚿳 | 𚿵 | 𚿶 | 𚿷 | 𚿸 | 𚿹 | 𚿺 | 𚿻 | 𚿽 | 𚿾 | |||

| Notes | ||||||||||||||||

The Unicode block for Small Kana Extension is U+1B130–U+1B16F:

| Small Kana Extension[1][2] Official Unicode Consortium code chart (PDF) | ||||||||||||||||

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | A | B | C | D | E | F | |

| U+1B13x | 𛄲 | |||||||||||||||

| U+1B14x | ||||||||||||||||

| U+1B15x | 𛅐 | 𛅑 | 𛅒 | 𛅕 | ||||||||||||

| U+1B16x | 𛅤 | 𛅥 | 𛅦 | 𛅧 | ||||||||||||

| Notes | ||||||||||||||||

In the following character sequences a kana from the /k/ row is modified by a handakuten combining mark to indicate that a syllable starts with an initial nasal, known as bidakuon. As of Unicode 16.0, these character combinations are explicitly called out as Named Sequences:

| Sequence name | Codepoints | Glyph | |

|---|---|---|---|

| HIRAGANA LETTER BIDAKUON NGA | U+304B | U+309A | か゚ |

| HIRAGANA LETTER BIDAKUON NGI | U+304D | U+309A | き゚ |

| HIRAGANA LETTER BIDAKUON NGU | U+304F | U+309A | く゚ |

| HIRAGANA LETTER BIDAKUON NGE | U+3051 | U+309A | け゚ |

| HIRAGANA LETTER BIDAKUON NGO | U+3053 | U+309A | こ゚ |

See also

[edit]- Bopomofo (Zhùyīn fúhào, "phonetic symbols"), a phonetic system of 37 characters for writing Chinese developed in the 1900s and which is more common in Taiwan.

- Iteration mark explains the iteration marks used with hiragana.

- Japanese phonology explains Japanese pronunciation in detail.

- Japanese typographic symbols gives other non-kana, non-kanji symbols.

- Japanese writing system

- Katakana

- Nüshu, a syllabary writing system used by women in China's Hunan province

- Shodō, Japanese calligraphy.

References

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ Dual 大辞林

「平」とは平凡な、やさしいという意で、当時普通に使用する文字体系であったことを意味する。 漢字は書簡文や重要な文章などを書く場合に用いる公的な文字であるのに対して、 平仮名は漢字の知識に乏しい人々などが用いる私的な性格のものであった。

Translation: 平 [the "hira" part of "hiragana"] means "ordinary, common" or "easy, simple" since at that time [the time that the name was given] it was a writing system for everyday use. While kanji was the official system used for letter-writing and important texts, hiragana was for personal use by people who had limited knowledge of kanji. - ^ "Japanese calligraphy". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 2017-06-22.

- ^ 山田 健三 (Yamada Kenzō). "平安期神楽歌謡文献からみる「平仮名」の位置" [The Position of "Hiragana" As Seen from Kagura Song References of the Heian Period] (PDF) (in Japanese). p. 239. Retrieved 2022-04-18.

[「かたかな」の「かた」は単に「片方」という意味ではなく、本来あるべきものが欠落しているという評価形容語と解すべきことはよく知られているが(亀井孝1941)、(7)としてまとめた対立関係から考えると、「ひらがな」も同様に「かな」の「ひら」という評価位置に存在するものと考えられる。

本国語大辞典「ひらがな」の説明は「ひら」を「角のない、通俗平易の意」とし、また「ひら」を前部要素とする複合語の形態素説明で、多くの辞書は「ひら」に「たいら」という意味を認める。

しかし、辞書の意味説明が必ずしも原義説明を欲してはいないことを知りつつも、野暮を承知でいうならば、これは「ひら」の原義(中核的意味)説明としては適当ではない。「ひら」は、「枚」や擬態語「ひらひら」などと同根の情態言とでもいうべき形態素/ pira /であり、その中核的意味は、物理的/精神的な「薄さ」を示し、「たいら」はそこからの派生義と思われる。となると、「ひらがな」に物理的「薄さ」(thinness)は当然求められないので、「ひら」とはより精神的な表現に傾き、「かたかな」同様、「かな」から見て、ワンランク下であることを示す、いささか差別的・蔑視的ニュアンスを含む表現であったということになる。

The "kata" in "katakana" does not mean just "one side", and it is well known (Takashi Kamei 1941) that it should be interpreted as a valuation epithet stating that something that should be there is missing, and considering the oppositional relationship summarized in figure (7), the word "hiragana" can be thought of in a valuation position as the "hira" kind of "kana".

The explanation of the term hiragana in the Nihon Kokugo Daijiten dictionary states that hira means "unangular, easy for common people", and descriptions of hira as a prefixing element in compounds as given in many dictionaries explain this hira as meaning "flat" (taira).

However, knowing that dictionary explanations of meaning do not always drive for the original senses, if we are to be brash, we might point out that this is not a fitting explanation of the original sense (core meaning) of hira. Hira is morpheme /pira/, cognate with words like 枚 (hira, "slip of paper, cloth, or something else flat") or ひらひら (hirahira, "flutteringly"), and the core meaning indicates physical or emotional "thinness", and taira ("flat") appears to be a derived meaning therefrom. As such, we naturally cannot get physical "thinness" from hiragana, so the hira leans more towards an emotional expression, and much like for katakana, from the perspective of kana, it indicates a lower relative ranking [relative to the kanji], and the expression contains a slight nuance of discrimination or contempt.

] - ^ Richard Bowring; Haruko Uryu Laurie (2004). An Introduction to Modern Japanese: Book 1. United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press. p. 9. ISBN 978-0521548878.

- ^ Liu, Xuexin (2009). "Japanese Simplification of Chinese Characters in Perspective". Southeast Review of Asian Studies. 31.

- ^ a b c d e f g h See obsolete kana.

- ^ "The Japanese Syllabaries (Hiragana)" (PDF). NHK World.

- ^ ■米国規格(ANSI Z39.11-1972)―要約. halcat.com (in Japanese). Archived from the original on 24 September 2015.

- ^ a b "ALA-LC Japanese Romanization Table" (PDF). Library of Congress. 2022. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2023-05-09. Retrieved 2023-05-09.

- ^ Kenkyusha's New Japanese-English Dictionary (Fourth ed.). Kenkyūsha. 1974.

- ^ "鼻濁音の位置づけと現況" (PDF).

- ^ "Unicode 10 Extended Kana Block" (PDF).

- ^ Walter & Walter 1998.

- ^ 伊豆での収穫 : 日本国語学史上比類なき変体仮名 [Harvest in Izu: Hentaigana unique in the history of Japanese linguistics]. geocities.jp (in Japanese).

- ^ a b Gross, Abraham (2020-01-05). "Proposal to Encode Missing Japanese Kana" (PDF).

- ^ "Unicode Kana Supplement" (PDF). unicode.org.

- ^ "Glyphwiki Hiraga Wu Reconstructed".

- ^ "仮名遣". 1891.

- ^ Iannacone, Jake (2020). "Reply to The Origin of Hiragana /wu/ 平仮名のわ行うの字源に対する新たな発見"

- ^ "Japanese full 50 kana: yi, ye, wu".

- ^ Yookoso! An Invitation to Contemporary Japanese 1st edition McGraw-Hill, page 13 "Linguistic Note: The Origins of Hiragana and Katakana"

- ^ Seeley (2000:19–23)

- ^ Richard Bowring; Haruko Uryu Laurie (2004). An Introduction to Modern Japanese: Book 1. United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press. p. 8. ISBN 978-0521548878.

- ^ Hatasa, Yukiko Abe; Kazumi Hatasa; Seiichi Makino (2010). Nakama 1: Introductory Japanese: Communication, Culture, Context 2nd ed. Heinle. p. 2. ISBN 978-0495798187.

- ^ p. 108. Kataoka, Kuniyoshi. 1997. "Affect and letter writing: unconventional conventions in casual writing by young Japanese women". Language in Society 26:103–136.

- ^ Unicode Named Character Sequences Database

Sources

[edit]- Yujiro Nakata, The Art of Japanese Calligraphy, ISBN 0-8348-1013-1, gives details of the development of onode and onnade.

Notes

[edit]- ^ を is transliterated as o in Modified Hepburn and Kunrei and as wo in Traditional Hepburn and Nippon-shiki.