Hinkley Point A nuclear power station

| Hinkley Point A nuclear power station | |

|---|---|

Hinkley Point A twin buildings housing the Magnox reactors | |

| |

| Country | England |

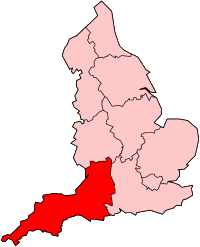

| Location | Hinkley Point, Somerset, South West England |

| Coordinates | 51°12′31″N 3°08′01″W / 51.2087°N 3.1337°W |

| Status | Decommissioning in progress |

| Construction began | November 1, 1957[1][2] |

| Commission date | |

| Decommission date | May 23, 2000[1][2] |

| Construction cost | £75 million est. [3] |

| Owners |

|

| Operator | Nuclear Restoration Services[4] |

| Nuclear power station | |

| Reactors | 2 (Units A-1 & A-2) |

| Reactor type | GCR - Magnox |

| Reactor supplier | English Electric & Babcock & Wilcox Ltd |

| Cooling source | Sea water (Severn Estuary) |

| Thermal capacity | 2 x 900 MWt[1][2] |

| Power generation | |

| Make and model | English Electric |

| Units decommissioned | |

| Nameplate capacity | 500 MWe[1][2] |

| Capacity factor | 72.4% (lifetime)[1][2] |

| Annual net output | 3,261 GW⋅h (11,740 TJ) (1994)[1][2] |

| External links | |

| Website | www |

| Commons | Related media on Commons |

grid reference ST211460 | |

Hinkley Point A nuclear power station is a former Magnox nuclear power station. It is located on a 19.4-hectare (48-acre) site in Somerset on the Bristol Channel coast, 5 miles (8 km) west of the River Parrett estuary. The ongoing decommissioning process is being managed by Nuclear Decommissioning Authority licensee Nuclear Restoration Services.

History

[edit]Hinkley Point A was one of three Magnox power stations located close to the mouth of the River Severn and the Bristol Channel, the others being Oldbury, and Berkeley.

The construction of the power station, which was undertaken by a consortium backed by English Electric, Babcock & Wilcox Ltd and Taylor Woodrow Construction,[5] began in 1957. The reactors and the turbines were supplied by English Electric.[6]

On 22 April 1966, the Minister of Power Richard Marsh officially opened the new nuclear power plant.[7][8]

In the late 1970s, two DEC PDP-11/40 mini-computers (One per reactor) were installed for Burst Can Detection and Reactor Temperature Monitoring, replacing the original instrumentation systems.[9] A DEC PDP-11/34 mini-computer was also installed for turbine parameter displays & logging, replacing the original systems.[10]

In 1988, reactor 2 set a world record for the longest continuous period of power generation from a commercial nuclear reactor, of 700 days and 7 hours.[11] Hunterston A Nuclear Power Station held the previous world record of 698 days.

Design

[edit]The power station, which is undergoing decommissioning, had two Magnox reactors, each supplying steam to three English Electric 93.5 MWe turbine generator sets which were all together across both reactors designed to produce 500 MWe net but, after de-rating of the reactor power output due to corrosion concerns, both reactors combined produced 470 MWe net.[12]

The design followed the principles established by the Calder Hall nuclear power station, in that it used a reactor core of natural uranium fuel in Magnox alloy cans within a graphite moderator, all contained in a welded steel pressure vessel. The core was cooled by CO2 pumped by six nominal 7,000 hp (5.2 MW) gas circulators, which transported the hot gas from the core to the six Steam Raising Units (boilers) via steel ducts. The gas circulators could be driven by induction motors supplied with mains electricity or, when steam was available, from one of the three 33MWe dedicated variable speed turbo alternator sets (One serving each reactor with one spare). The design pressure of the gas circuit was 185 psig, and the temperature of the gas leaving the reactor was 378 °C (712 °F), although this was later reduced when the hot CO2 was found to be corroding the mild steel components of the gas circuit more quickly than had been anticipated. Like all Magnox reactors, Hinkley Point A was designed for on-load refuelling so that exhausted fuel elements could be replaced with fresh without shutting down the reactor.

While primarily planned for peaceful electricity generation, Hinkley Point A was modified so that weapons-grade plutonium could be extracted for military purposes should the need arise.[13][14]

Five 1,050 hp English Electric 8CSV emergency diesel generators were installed at Hinkley Point A, for use in the event of loss of grid supplies.

Specification

[edit]| Parameter | |

|---|---|

| Output of main turbines | 6 x 93.5 MW 500 MW |

| Area of main station | 16.2 ha (40 acres) |

| Fuel per reactor | 355 t (349 tons) |

| Fuel | Natural Uranium |

| Fuel cans | Magnox |

| Fuel surface temperature | about 430 °C (806 °F) |

| CO2 pressure | 12.7 bar g (185 lb/in2 g) |

| CO2 channel outlet temperature | 387 °C (729 °F) |

| Number of channels per reactor | 4500 |

| Total weight of graphite per core | 1891 t (1861 tons) |

| Steam conditions turbine stop valve HP | 45.5 bar g (660 lb/in2 g) 363 °C (685 °F) |

| Steam conditions turbine stop valve IP | IP 12.7 bar g (183 lb/in2 g) 354 °C (669 °F) |

Capacity and output

[edit]The generating capacity, electricity output, load factor and thermal efficiency was as shown in the table.[16]

| Year | Net capability, MW | Electricity supplied, GWh | Load as percent of capability, % | Thermal efficiency, % |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1972 | 663.9 | 657.122 | 16.2 | 22.2 |

| 1979 | 543.9 | 3,207.368 | 85.1 | 24.15 |

| 1981 | 543.9 | 3,131.881 | 83.1 | 24.43 |

| 1982 | 543.9 | 3,033.583 | 80.5 | 24.26 |

| 1984 | 430 | 3,256.091 | 86.2 | 24.27 |

Gas circulator design problem

[edit]

In August 1963, during a hot run test on the first reactor, which had not then been loaded with nuclear fuel, problems were encountered due to noise from the single stage axial flow gas circulators. This could be heard up to 5 miles (8.0 km) away, and personnel working at the station had to wear ear defenders. After unexplained drops in the mass flow rate and motor driving current in number 3 and 5 gas circulators, the hot run tests were stopped and the gas circuit opened up. Severe mechanical damage to the blading and diffuser sections of the number 3 and 5 gas circulators was observed. Large sections of the diffusers had broken away, and extensive fatigue cracking was found in the outer tapering shell and central axial cone. Large pieces of the diffuser casing had entered the gas circulator blades and caused heavy impact damage, and large amounts of debris had been transported down the gas duct. The Inlet Guide Vanes (IGVs), which were provided to enable the performance of individual gas circulators to be "trimmed," were found to be extensively damaged, and the rotor blades and outlet guide vanes also had extensive impact and fatigue damage. Large numbers of the nuts and bolts involved had been shaken loose.[17]

The subsequent investigation determined that the noise was caused by interaction between the IGVs and the rotor blades. The sound pressure levels generated by this noise were high enough to cause rapid fatigue failure in gas circuit components, and major re-design of the gas circulators and associated components was required. The IGVs were scrapped and flow straighteners introduced to smooth the flow of gas into the gas circulator intakes. Much pioneering experimental laboratory work on resonance and sound pressure levels was performed at English Electric's Gas Turbine and Atomic Power Division (APD) facilities at Whetstone, Leicestershire, to support the redesign work, and instrumentation to measure stress and sound pressure levels in the gas circuit during testing was developed. The delay caused severe financial difficulties for the consortium and set the construction schedule back; the station began generating electricity two years late in February 1965.[18]

Turbine failure

[edit]The importance of materials design and the understanding of grain boundaries was highlighted during the operation of Hinkley Point. In 1969 there was a catastrophic failure of the Hinkley Point 'A' turbine-generator at near normal speeds (3,200 rev/min). The interaction of fragments of the burst disc and the shaft caused the adjacent disc to burst almost immediately afterwards, and in the general disruption that followed another disc disintegrated completely and the entire unit was irreparably damaged. This is thought to be the first catastrophic failure of a turbine-generator in Britain. The characteristics of the material from which the burst discs were made were a contributory factor in the failure. The 3 Cr-Mo steel made by the a.0.h. process was temper embrittled during slow furnace cooling after heat treatment and therefore had poor fracture toughness, i.e. low tolerance of very sharp crack-like defects in highly stressed regions. Such material can of course be used quite safely in highly stressed regions in the absence of cracks. A material of higher fracture toughness would have tolerated larger cracks without succumbing to their unstable propagation, and the failure would have been postponed if not avoided. At the time of the manufacture of these discs, it was not possible to quantify the effect of embrittlement on the material's ability to tolerate small cracks in the most highly stressed regions.[19] The reason for the failure was down to transport of phosphor towards the grain boundaries which embrittled the chromium steel causing it to fail.[20][21][22]

Closure and decommissioning

[edit]Both reactors were shut down in April 1999 to carry out reinforcement work following a Nuclear Installations Inspectorate Periodic Safety Review. Reactor 2 was returned to service in September 1999, but shut down on 3 December 1999 because of newly identified uncertainties in the reactor pressure vessel material properties. Examinations at a sister site identified irregularities in weld materials on various reactor penetrations. To access and test these materials at Hinkley Point would require bespoke remote access (robotics possibly) and a timescale exceeding a year. Also at this time an expensive project was underway to thermally lag the exterior of the steel pressure vessel to improve thermal efficiency. The cost of this impending project required a guaranteed operating extension for an acceptable ROI. Because of the cost of remedying these problems, and with no guarantees of a timely solution, Magnox announced on 23 May 2000 that Hinkley Point A would be shut down.[23]

Hinkley Point A was one of 11 Magnox nuclear power stations commissioned in the United Kingdom between 1956 and 1971. During its 35 years of operation, Hinkley Point A generated more than 103 TWh of electricity, giving a lifetime load factor against design of 34%.[24]

The ongoing decommissioning process and site works are being managed by Nuclear Decommissioning Authority subsidiary Nuclear Restoration Services.

Defuelling and removal of most buildings is expected to take until 2031, followed by a care and maintenance phase from 2031 to 2085. Demolition of reactor buildings and final site clearance is planned for 2081 to 2091.[25]

Site future

[edit]The Hinkley Point Site was organized as two nuclear power stations: next to Hinkley Point A with its two Magnox reactor buildings there is Hinkley Point B, operated by EDF Energy, with two AGCR reactors in one building.

In October 2013, the UK government announced that it had approved the construction of Hinkley Point C. This new plant, consisting of two EPR units; Unit 1 was originally scheduled to be completed in 2025 and Unit 2 in 2026 and both would remain operational for around 60 years.[26]

See also

[edit]- Energy policy of the United Kingdom

- Energy use and conservation in the United Kingdom

- Hinkley Point B nuclear power station

- Hinkley Point C nuclear power station

- Magnox

- Magnox Reprocessing Plant

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h "HINKLEY POINT A-1". Public Reactor Information System. IAEA. 29 August 2022. Retrieved 30 August 2022.

- ^ a b c d e f g h "HINKLEY POINT A-2". Public Reactor Information System. IAEA. 29 August 2022. Retrieved 30 August 2022.

- ^ Reactors UK. United Kingdom Atomic Energy Authority. 1964. p. 70.

- ^ "About Us". GOV.UK. Nuclear Restoration Services. Retrieved 26 October 2024.

- ^ "Nuclear Development in the United Kingdom". Archived from the original on 17 January 2014. Retrieved 22 January 2014.

- ^ "Nuclear Power Plants in the UK". Archived from the original on 19 July 2009. Retrieved 11 April 2009.

- ^ "The Electrical Review". Electrical Review. 178 (9–17): 638. 1966.

- ^ "Nuclear Technology Society in the German Atomic Forum". Handelsblatt GMBH. 11: 50, 225. 1966.

- ^ "Micro Consultants supplies data loggers for Hinkley Point". Electronics & Power. 22 (2): 74. 1976. doi:10.1049/ep.1976.0038.

- ^ C. F. Unsworth (1987). "Updating the control and instrumentation systems on an operational nuclear power station". Journal of the Institution of Electronic and Radio Engineers. 57 (4): 156–160. doi:10.1049/jiere.1987.0057.

- ^ Joining & Materials. Welding Institute. 1988. p. 258.

- ^ "PRIS - Reactor Details Hinkley A1". PRIS. Retrieved 28 July 2015.

- ^ David Lowry (13 November 2014). "The world's first 'Nuclear Proliferation Treaty'". Ecologist. Retrieved 2 December 2014.

- ^ Reginald Maudling (24 June 1958). "Atomic Power Stations (Plutonium Production)". Parliamentary Debates (Hansard). HC Deb 24 June 1958 vol 590 cc246-8. Retrieved 2 December 2014.

the Central Electricity Generating Board has agreed to a small modification in the design of Hinkley Point and of the next two stations in its programme so as to enable plutonium suitable for military purposes to be extracted should the need arise.

- ^ Hinkley Point B Nuclear Power Station. London: Central Electricity Generating Board. April 1971. p. 4.

- ^ CEGB Statistical Yearbooks 1972–84, CEGB, London

- ^ "Investigations into the failure of gas circulators and circuit components at Hinkley Point nuclear power station" Rizk, W and Seymour, D F Proceedings of the Institution of Mechanical Engineers, v179 1964 p627-703

- ^ "Hinkley A: 1965". BBC Somerset. BBC. Retrieved 5 July 2008.

- ^ Kalderon, D. (1972). Steam Turbine Failure at Hinkley Point "A." Proceedings of the Institution of Mechanical Engineers, 186(1), 341–377. https://doi.org/10.1243/PIME_PROC_1972_186_037_02

- ^ Seah, M. P. (1977). Grain boundary segregation and the T-t dependence of temper brittleness. Acta Metallurgica, 25(3), 345–357. https://doi.org/10.1016/0001-6160(77)90153-5

- ^ Lejček, P., & Hofmann, S. (1995). Thermodynamics and structural aspects of grain boundary segregation. Critical Reviews in Solid State and Materials Sciences, 20(1), 1–85. https://doi.org/10.1080/10408439508243544

- ^ Lozovoi, A. Y., Paxton, A. T., & Finnis, M. W. (2006). Structural and chemical embrittlement of grain boundaries by impurities: A general theory and first-principles calculations for copper. Physical Review B - Condensed Matter and Materials Physics, 74(15), 155416. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevB.74.155416

- ^ Nuclear Installations Inspectorate (September 2000). Report by HM Nuclear Installations Inspectorate on the results of Magnox Long Term Safety Reviews (LTSRs) and Periodic Safety Reviews (PSRs) (PDF) (Report). Health and Safety Executive. p. 37 (Appendix E). Archived from the original (PDF) on 26 May 2006. Retrieved 21 March 2010.

- ^ "Hinkley Point A - Facts and figures". Magnox Ltd. Archived from the original on 17 August 2011. Retrieved 7 February 2011.

- ^ "The 2010 UK Radioactive Waste Inventory: Main Report" (PDF). Nuclear Decommissioning Agency/Department of Energy & Climate Change. February 2011. Archived from the original (PDF) on 25 March 2012. Retrieved 22 May 2012.

- ^ "UK nuclear power plant gets go-ahead". BBC News. 21 October 2013. Retrieved 21 October 2013.

External links

[edit] Media related to Hinkley Point A Nuclear Power Station at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Hinkley Point A Nuclear Power Station at Wikimedia Commons- Hinkley Point. Technical & Scientific Films Ltd. English Electric, Babcock & Wilcox, Taylor Woodrow. c. 1965 – via YouTube. (part 2), film about the construction and commissioning of Hinkley Point A