Hikurangi Plateau

| Hikurangi Plateau | |

|---|---|

| Stratigraphic range: Cretaceous | |

| Type | Igneous |

| Area | 400,000 km2 (150,000 sq mi), but was 800,000 km2 (310,000 sq mi) before more recent subduction[1] |

| Lithology | |

| Primary | Basalt |

| Location | |

| Coordinates | 40°S 179°E / 40°S 179°E |

| Region | South Pacific Ocean |

| Country | New Zealand |

| Type section | |

| Named for | Mount Hikurangi, in Māori mythology the first part of the North Island to emerge from the ocean |

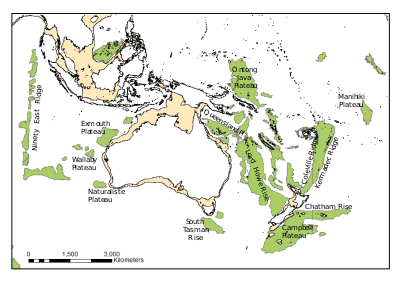

One of the major divisions of Zealandia, the Hikurangi Plateau (top right) drifted south and collided with parts of the mostly submerged continent. | |

The Hikurangi Plateau is an oceanic plateau in the South Pacific Ocean east of the North Island of New Zealand. It is part of a large igneous province (LIP) together with Manihiki and Ontong Java, now located 3,000 km (1,900 mi) and 3,500 km (2,200 mi) north of Hikurangi respectively.[2] Mount Hikurangi, in Māori mythology the first part of the North Island to emerge from the ocean, gave its name to the plateau.

Geological setting

[edit]The Hikurangi Plateau covers approximately 400,000 km2 (150,000 sq mi) and reaches 2,500–3,000 m (8,200–9,800 ft) below sea level.[1]

Hikurangi Plateau is cut by the Hikurangi Channel, a 2000 km abyssal channel that starts at Kaikōura and runs along the Hikurangi Trough as far as the Māhia Peninsula before crossing the plateau and ending in the South-west Pacific abyssal plain.[3]

Tectonic evolution

[edit]Two models have been proposed for the formation of Hikurangi. It could be derived from the mantle plume that caused the break-up of Gondwana and the separation of Zealandia from Antarctica 107 Ma. Alternatively, it could have formed together with other Pacific plateaux around 120 Ma as part of the Ontong Java-Manihiki-Hikurangi mega-plateau, in which case Hikurangi must have drifted thousands of kilometres during the Cretaceous silent period (84–121 Ma) before colliding with Gondwana.[2] This later model (which does not exclude its initiation from a mantle plume) is the only one consistent with the current best fit Pacific Plate reference frame tectonics model where the Osbourn Trough is modelled as a spreading centre between the Manihiki Plate and the Hikurangi Plate which later became fixed components of today's Pacific Plate.[4]

A 2010 study of isotopic data supported the mega-plateau or "Greater Ontong Java Event" model. The study added several basins as remains of this LIP event, including the north-west part of the Central Pacific, Nauru, East Mariana, and Lyra basins — submarine volcanism that must have covered 1% of Earth's surface and had a dramatic impact on life on Earth. The samples so far taken from the three plateaus are all consistent with ages of initial formation about 124 million years ago.[2][5] There are, nevertheless, traces in seamounts on Hikurangi of a second Late Cretaceous magmatic event contemporaneous with volcanism on New Zealand and associated with the final break-up of Gondwana.

The Hikurangi Plateau has been partly subducted under the Chatham Rise, probably during the Cretaceous, and probably resulting in a slab more than 150 km (93 mi) long. The western margin of the plateau is actively subducting under the North Island of New Zealand to a depth of 65 km (40 mi). With these missing portions of the plateau added to it, the Hikurangi Plateau originally must have covered 800,000 km2 (310,000 sq mi), an area similar to that of the Manihiki Plateau 3,000 km (1,900 mi) to the north.[1]

The Hikurangi Plateau first subducted beneath New Zealand around 100 Ma during the Gondwana collision and it is currently subducting a second time as part of the convergence between the Pacific and Australian plates. These subducted parts are reaching 37–140 km (23–87 mi) into the mantle beneath the North Island and northern South Island.[6] The extent of the Hikurangi Plateau slab suggests that it has played a significant role in the geology of New Zealand during the past 100 Ma. The Southern Alps in central South Island are being uplifted along the plate boundary there, a fault zone which parallels the western edge of the slab of the Hikurangi Plateau.[7]

The Australian and Pacific plates converge obliquely in the Tonga-Kermadec-Hikurangi subduction zone. The Hikurangi Plateau alters this subduction beneath North Island, at the Hikurangi subduction zone, where the buoyancy of the slab has resulted in the exposure of a forearc and hence earthquakes such as the 7.8 Mw 1931 Hawke's Bay earthquake.[8]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ a b c Hoernle et al. 2010, Geological overview, morphology and rock types, pp. 7198–7200

- ^ a b c Hoernle et al. 2010, Introduction, pp. 7196–7198

- ^ Lewis, Nodder & Carter 2009

- ^ Torsvik, Trond H.; Steinberger, Bernhard; Shephard, Grace E.; Doubrovine, Pavel V.; Gaina, Carmen; Domeier, Mathew; Conrad, Clinton P.; Sager, William W. (2019). "Pacific‐Panthalassic reconstructions: Overview, errata and the way forward". Geochemistry, Geophysics, Geosystems. 20 (7): 3659–3689. Bibcode:2019GGG....20.3659T. doi:10.1029/2019GC008402. hdl:10852/73922. S2CID 198414127.

- ^ Timm, Christian; Hoernle, Kaj; Werner, Reinhard; Hauff, Folkmar; van den Bogaard, Paul; Michael, Peter; Coffin, Millard F.; Koppers, Anthony (2011). "Age and geochemistry of the oceanic Manihiki Plateau, SW Pacific: New evidence for a plume origin". Earth and Planetary Science Letters. 304 (1–2): 135-146. Bibcode:2011E&PSL.304..135T. doi:10.1016/j.epsl.2011.01.025. ISSN 0012-821X.

- ^ Reyners, Eberhart-Phillips & Bannister 2011, Abstract

- ^ Reyners, Eberhart-Phillips & Bannister 2011, Discussion, pp. 170–171

- ^ Henrys et al. 2006, Hikurangi subduction zone, p. 777

Sources

[edit]- Henrys, S.; Reyners, M.; Pecher, I.; Bannister, S.; Nishimura, Y.; Maslen, G. (2006). "Kinking of the subducting slab by escalator normal faulting beneath the North Island of New Zealand". Geology. 34 (9): 777–780. Bibcode:2006Geo....34..777H. doi:10.1130/G22594.1. Retrieved 11 December 2016.

- Hoernle, K.; Hauff, F.; van den Bogaard, P.; Werner, R.; Mortimer, N.; Geldmacher, J.; Garbe-Schönberg, D.; Davy, B. (2010). "Age and geochemistry of volcanic rocks from the Hikurangi and Manihiki oceanic plateaus" (PDF). Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta. 74 (24): 7196–7219. Bibcode:2010GeCoA..74.7196H. doi:10.1016/j.gca.2010.09.030. Retrieved 11 December 2016.

- Lewis, Keith; Nodder, Scott D.; Carter, Lionel (2009). "Sea floor geology – Hikurangi Plateau". Te Ara – the Encyclopedia of New Zealand. Retrieved 11 December 2016.

- Reyners, M.; Eberhart-Phillips, D.; Bannister, S. (2011). "Tracking repeated subduction of the Hikurangi Plateau beneath New Zealand". Earth and Planetary Science Letters. 311 (1): 165–171. Bibcode:2011E&PSL.311..165R. doi:10.1016/j.epsl.2011.09.011. Retrieved 11 December 2016.