Henry Lee Moon

Henry Lee Moon | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | July 20, 1901 Pendleton, South Carolina, United States |

| Died | June 7, 1985 (aged 84) New York City, New York, United States |

| Occupation(s) | Journalist, activist |

| Years active | 1925 – 1974 |

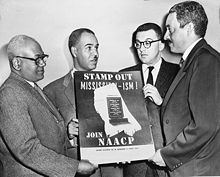

Henry Lee Moon (1901 – June 7, 1985) was an American journalist, writer and civil rights activist. He worked for The Amsterdam News and the NAACP.

Early life and career

[edit]Moon was born in Pendleton, South Carolina[1] in 1901. He spent much of his life in Cleveland, Ohio. His father Roddy K. Moon established the Cleveland branch of the NAACP in 1912.

Moon attended Howard University where he served as the editor of the school's University Journal. He then received a master's degree in journalism from Ohio State University. Moon's goal at the time was to become the first black journalist to work for a white-owned newspaper. However, in 1925 he went to work in public relations at the Tuskegee Institute instead.[2]

In 1931, he achieved his dream of becoming a newspaperman when he was offered a job at the African-American weekly The Amsterdam News. He moved to New York City and began writing book reviews and essays for the publication. The same year, he collaborated with fellow News journalist Ted Poston on a series of articles focusing on capital crimes. The two men became roommates and remained best friends for the rest of their lives.[3] In 1932, they traveled to the Soviet Union with Langston Hughes and Moon's future wife Mollie Lewis to make an anti-segregation film called Black and White. The film was cancelled at the last minute by the Mezhrabpomfilm studio, causing Moon to have a lifelong disillusionment with the Communists. Unbeknownst to Moon, engineer Hugh Lincoln Cooper had threatened to stop work on the high-profile Dnieper Dam if the Soviet government did not halt the production of the film, which he viewed as un-American.[4]

After he returned to the US, Moon got a job with the Public Works Administration under Harold L. Ickes and continued to write for The Amsterdam News. Moon was fired from the paper after he encouraged the staff to join The Newspaper Guild union. He then went to work for the Federal Writers' Project until federal funding for it was ended in 1939. Moon applied to the New York Times, but was rejected. He found work in Washington, D.C., working for Robert C. Weaver on Franklin D. Roosevelt's Black Cabinet as a race relations advisor. After the war, he worked as an organizer for the PAC of the CIO trade union.[5]

In 1948, Moon began working for the NAACP as their public relations director. Moon held the position until 1974. During his tenure at the NAACP, he promoted voting rights and encouraged the organization to work harder to elect politicians friendly to their cause. While at the NAACP, he also wrote the book Balance of Power and edited a collection of W. E. B. Du Bois' writings.[6]

Death and legacy

[edit]Moon died on June 7, 1985, at Mount Sinai Hospital in New York City, New York.[6] In 1988, the library at the NAACP's headquarters in Baltimore was renamed in his memory.[7]

Personal life

[edit]Moon married Mollie Lewis on August 13, 1938. The couple became well-known for throwing integrated society parties that allowed black and white New Yorkers to meet and connect with each other. Their reputation was satirized in Chester Himes' 1961 novel Pinktoes.[8]

Works

[edit]- 1948 Balance of Power: The Negro Vote (Doubleday)

- 1957 The New Subversion of the Fifteenth Amendment (Howard University)

- 1972 The Emerging Thought of W.E.B. DuBois, editor (Simon & Schuster)

References

[edit]- ^ National Archives at St. Louis; St. Louis, Missouri; WWII Draft Registration Cards for New York City, 10/16/1940 - 03/31/1947; Record Group: Records of the Selective Service System, 147

- ^ Greene, Lorenzo Johnston (1996). Selling Black History for Carter G. Woodson: A Diary, 1930-1933. University of Missouri Press. p. 91. ISBN 0826210694.

- ^ Hauke, Kathleen (1998). Ted Poston: Pioneer American Journalist. University of Georgia Press. pp. 38–9. ISBN 082032020X.

- ^ Lee, Steven (2015). The Ethnic Avant-Garde: Minority Cultures and World Revolution. Columbia University Press. p. 142. ISBN 0231540116.

- ^ Dawson, Michael (2013). Blacks In and Out of the Left. Harvard University Press. p. 75. ISBN 0674074017.

- ^ a b Berger, Joseph (June 8, 1985). "HENRY LEE MOON DEAD AT 84; EX-N.A.A.C.P. SPOKESMAN". New York Times.

- ^ Williams, James (June–July 1988). "Moving Ceremonies Precede Opening of Moon Library". The Crisis. p. 56.

- ^ Hauke, Kathleen (1998). Ted Poston: Pioneer American Journalist. University of Georgia Press. pp. 157–8. ISBN 082032020X.