Qilian Mountains

39°12′N 98°32′E / 39.200°N 98.533°E

| Qilian Mountains | |

|---|---|

| 祁連山 | |

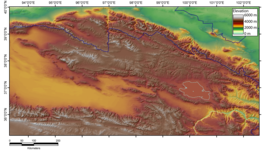

Qilian Mountains in Qilian County, Qinghai | |

| Highest point | |

| Peak | Kangze'gyai |

| Elevation | 5,808 m (19,055 ft) |

| Geography | |

| Location | Gansu and Qinghai provinces, China |

The Qilian Mountains (Tibetan: མདོ་ལ་རིང་མོ),[a] together with the Altyn-Tagh sometimes known as the Nan Shan,[b] as it is to the south of the Hexi Corridor, is a northern outlier of the Kunlun Mountains, forming the border between Qinghai and the Gansu provinces of northern China.[1]

Geography

[edit]The range stretches from the south of Dunhuang some 800 km to the southeast, forming the northeastern escarpment of the Tibetan Plateau and the southwestern border of the Hexi Corridor.

The eponymous Qilian Shan peak, situated some 60 km south of Jiuquan, at 39°12′N 98°32′E / 39.200°N 98.533°E, rises to 5,547 m. It is the highest peak of the main range, but there are two higher peaks further south, Kangze'gyai at 38°30′N 97°43′E / 38.500°N 97.717°E with 5,808 m and Qaidam Shan peak at 38°2′N 95°19′E / 38.033°N 95.317°E with 5,759 m. Other major peaks include Gangshiqia Peak in the east.

The Nan-Shan range continues to the west as Yema Shan (5,250 m) and Altun Shan (Altyn Tagh) (5,798 m). To the east, it passes north of Qinghai Lake, terminating as Daban Shan and Xinglong Shan near Lanzhou, with Maoma Shan peak (4,070 m) an eastern outlier. Sections of the Ming dynasty's Great Wall pass along its northern slopes, and south of northern outlier Longshou Shan (3,616 m).

The Qilian mountains are the source of numerous, mostly small, rivers and creeks that flow northeast, enabling irrigated agriculture in the Hexi Corridor (Gansu Corridor) communities, and eventually disappearing in the Alashan Desert. The best known of these streams is the Ejin (Heihe) River. The region has many glaciers, the largest of which is the Touming Mengke.[2] These glaciers have undergone acceleration in their melting in recent decades.[3]

Lake Hala is a large brackish lake, located within the Qilian mountains.

The characteristic ecosystem of the Qilian Mountains has been described by the World Wildlife Fund as the Qilian Mountains conifer forests.[4]

Biandukou (扁都口), with an altitude of over 3500 m, is a pass in the Qilian Mountains. It links Minle County of Gansu in the north and Qilian County of Qinghai in the south.[5]

History

[edit]

The Shiji mentions the name "Qilian mountains" together with Dunhuang in relation to the homeland of the Yuezhi.[6] These Qilian Mountains however, has been suggested to be the mountains now known as Tian Shan, 1,500 km to the west.[7] Dunhuang has also been argued to be the Dunhong mountain.[8] Qilian (祁连) is said to be a Xiongnu word meaning "sky" (Chinese: 天) according to Yan Shigu, a Tang dynasty commentator on the Hanshu.[9] Sanping Chen (1998) suggested that 天 tiān, 昊天 hàotiān, 祁連 qílián, and 赫連 Hèlián were all cognates and descended from multisyllabic Proto-Sinitic *gh?klien.[10] Schessler (2014) objects to Yan Shigu's statement that 祁連 was a Xiongnu word; he reconstructs 祁連's pronunciation in around 121 BCE as *gɨ-lian, apparently the same etymon as 乾 (☰) the Trigram for "Heaven", in standard Chinese qián < Middle Chinese QYS *gjän < Eastern Han Chinese gɨan < Old Chinese *gran, which Schuessler etymologizes as from Proto-Sino-Tibetan and related to Proto-Tibeto-Burman *m-ka-n, cognate with Written Tibetan མཁའ (Wylie transliteration: mkha') “heaven”.[11][12]

The Tuyuhun were based around the Qilian mountains.

The mountain range was formerly known in European languages as Richthofen Range after Ferdinand von Richthofen, who was the Red Baron's explorer-geologist uncle.[13]

The mountain range gives its name to Qinghai's Qilian County.

Notes

[edit]- ^ Chinese pronunciation: [tɕʰǐljæ̌n ʂán]; simplified Chinese: 祁连山; traditional Chinese: 祁連山; pinyin: Qílián Shān; Mongghul: Chileb

- ^ Chinese pronunciation: [nǎnʂán]; Chinese: 南山; pinyin: Nánshān; lit. 'South(ern) Mountains'

References

[edit]- ^ The Journal of Asian studies. Vol. 62. Association for Asian Studies. 2003. p. 262. ISBN 0-691-09676-7. Retrieved 2010-06-28.

- ^

"Top 6 most beautiful glaciers in China". China Daily. 2012-07-15. Retrieved 2017-04-18.

It can be found in Laohu Valley on the northern slope of Daxue Mountain in Subei County.

- ^ Wong, Edward (2015-12-08). "Chinese Glacier's Retreat Signals Trouble for Asian Water Supply". New York Times. p. A4. Retrieved 2017-04-18.

- ^ "Qilian Mountains conifer forests". Terrestrial Ecoregions. World Wildlife Fund.

- ^ "扁都口旅游景区开发项目" [Flat mouth tourist area development project] (in Chinese). Xinhua. 2005-12-20. Archived from the original on 2016-03-04. Retrieved 2017-04-18.

- ^ Sima Qian et al., Shiji vol 123: "Account of Dayuan" quote: "始月氏居敦煌、祁連閒". translation: "Initially the Yuezhi dwelt between Dunhuang and Qilian."

- ^ Mallory, J. P. & Mair, Victor H. (2000). The Tarim Mummies: Ancient China and the Mystery of the Earliest Peoples from the West. Thames & Hudson. London. p. 58. ISBN 0-500-05101-1.

- ^ Liu, Xinru, Migration and Settlement of the Yuezhi-Kushan: Interaction and Interdependence of Nomadic and Sedentary Societies (2001) [1]

- ^ 班固 (20 August 2015). 漢書: 顏師古註.

祁連山即天山也,匈奴呼天為祁連 (translation: Qilian Mountain is the Tian Shan, the Xiongnu called the sky qilian)

- ^ Chen, Sanping. "Sino-Tokharico-Altaica — Two Linguistic Notes". Central Asiatic Journal. 42 (1): 33-37.

- ^ Schuessler, Axel (2014). "Phonological Notes on Hàn Period Transcriptions of Foreign Names and Words". Studies in Chinese and Sino-Tibetan Linguistics: Dialect, Phonology, Transcription and Text - Language and Linguistics Monograph Series. Taipei, Taiwan: Institute of Linguistics, Academia Sinica (53). p. 274 of 249-292. archived from original

- ^ Schuessler, Axel. 2007. An Etymological Dictionary of Old Chinese. University of Hawaii Press. p. 425

- ^ Winchester, Simon. (2008). The Man Who Loved China: the Fantastic Story of the Eccentric Scientist Who Unlocked the Mysteries of the Middle Kingdom, p. 126.

External links

[edit]- Winchester, Simon. (2008). The Man Who Loved China: the Fantastic Story of the Eccentric Scientist Who Unlocked the Mysteries of the Middle Kingdom. New York: Harper. ISBN 978-0-06-088459-8

Media related to Qilian Mountains at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Qilian Mountains at Wikimedia Commons- peakbagger.com

- Climatological Information (Reference) for Qilian Shan