Hedareb people

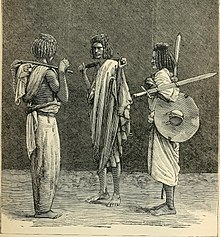

An illustration of "Beni Amer" men, from 1888 | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

|---|---|

100,000[1]–202,000[2] | |

| Languages | |

| Beja, Tigre, Arabic | |

| Religion | |

| Sunni Islam | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| other Beja and other Cushitic peoples |

The Hedareb or T'bdawe[note 1] are a Cushitic ethnic group native to northwestern Eritrea.[3] They are a subgroup of the Beja.[4] They are more diverse than the other Eritrean ethnicities; one subgroup speaks the traditional Beja language, which belongs to the Cushitic branch of the Afro-Asiatic family, while another is more closely related to Sudanese Hadendoa. They are among the least-researched groups in Eritrea.[5]

The Hedareb people live in northwestern Eritrea and extend as far as the borders with east Sudan.[6] Nomadic or semi-nomadic pastoralists, they typically migrate seasonally with their herds of camels, goats and sheep.[3]

Language

[edit]The Hedareb speak the Beja language or Tigre language as a mother tongue.[6] In addition to their variety of Beja, known as Hedareb or T’badwe, most Hedareb people also speak at least one other language, typically for a larger group Tigre, and for a small group Arabic as well.[7]

Society

[edit]Hedareb society is hierarchical, and is traditionally organized into clans and subclans.[6] Hedarebs are a Muslim group,[5] and most are Sunni Muslims.[3] Marriages are typically arranged to maximize alliances between extended families. It is customary for the groom's family to pay a bride price of five to twelve goats, and a varying amount of money,[8] or as much as 70 camels.[9]

Sociologist Abdulkader Saleh Mohammad writes that the Hedareb have been excluded from state conceptions of Eritrean nationhood and have become a marginalized group with many members who do not feel connected to the Eritrean nation-state.[10]

Laws

[edit]As Muslim people, the Hedareb follow Sharia law in most matters.[5]

In the nineteenth century, blood feuds marked by chains of revenge killings existed among Hedareb groups; unlike those among neighboring groups, they were rarely resolved by the payment of blood money, possibly because the Hedareb had fewer trading practices.[5] Also distinctively, killing one's wife was traditionally punished by death, while killing one's children went unpunished.[5] Rape of a noblewoman by a serf was punishable by death, while rape of serfs by nobles was tolerated.[5]

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Hedareb, t'badwe, to-bedawye and bedawi may refer to the people or their language. Beja is an Arabic name for the language; Hedareb may be a corruption of Hadarma, "people of the Hadhramaut". See Tesfagiorgis G., Mussie (2010). Eritrea. p. 178 and 216. ISBN 9781598842319. and Paul, A. (1959). "THE HADĀREB: A Study in Arab—Beja Relationships". Sudan Notes and Records. 40. University of Khartoum: 75–78. JSTOR 41719580.

References

[edit]- ^ Mehbratu, S; Habtezion, Zerisenay (2009). Eritrea: Constitutional, Legislative and Administrative Provisions Concerning Indigenous Peoples. International Labour Organization; African Commission’s Working Group on Indigenous Communities/Populations in Africa; Centre for Human Rights, University of Pretoria; with support from the European Commission. doi:10.2139/ssrn.1584657. SSRN 1584657. Asserts Hedareb population is 2% of the total population of 4.8 million.

- ^ "About Eritrea: People". eritreanconsulate-lb.com. Honorary Consulate of The State of Eritrea in Lebanon. Archived from the original on 1 May 2018. Retrieved 28 February 2015.

- ^ a b c "The People of Eritrea". www.eritrean-embassy.se. Eritrean Embassy in Sweden. Archived from the original on 28 October 2018. Retrieved 27 February 2015.

- ^ "Beni Amir: The Hedareb in Eritrea". EriStory. 2017-06-15. Retrieved 2022-10-26.

- ^ a b c d e f Favali, L.; Pateman, R. (2003). Blood, Land, and Sex: Legal and Political Pluralism in Eritrea. Blood, Land, and Sex. Indiana University Press. ISBN 978-0-253-10984-2. Retrieved Jul 30, 2017.

- ^ a b c Tesfagiorgis G., Mussie (2010). Eritrea. ABC-CLIO. p. 178. ISBN 978-1598842319.

- ^ Killion, Tom (1998). Historical Dictionary of Eritrea. The Scarecrow Press. ISBN 0-8108-3437-5.

- ^ Tesfagiorgis G., Mussie (29 October 2010). Eritrea. pp. 194–195. ISBN 9781598842326.

- ^ Gebremedhin, T.G. (2002). Women, Tradition and Development: A Case Study of Eritrea. Red Sea Press. ISBN 978-1-56902-153-8. Retrieved Jul 30, 2017.

- ^ Mohammad, Abdulkader Saleh (2013). "Competing identities and the emergence of Eritrean Nationalism between 1941 and 1952". “African Dynamics in Multipolar World”. 5th European Conference on African Studies. Lisbon: Centro de Estudos Internacionais do Instituto Universitário de Lisboa (ISCTE-IUL). pp. 1376–1408. 978-989-732-364-5. Retrieved 18 February 2016.

External links

[edit]- YouTube videos of traditional Hedareb dance: [1], [2]

- Eritrean Ministry of Information: Traditional Wedding Ceremonies of the Hedareb Part I Archived 2015-09-24 at the Wayback Machine and Part II Archived 2016-03-04 at the Wayback Machine

Further reading

[edit]- Paul, A. (1959). "THE HADĀREB: A Study in Arab—Beja Relationships". Sudan Notes and Records. 40. University of Khartoum: 75–78. JSTOR 41719580.