Hectorite

| Hectorite | |

|---|---|

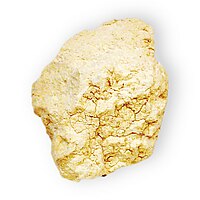

Hectorite from California | |

| General | |

| Category | Phyllosilicates Smectite |

| Formula (repeating unit) | Na0.3(Mg,Li)3Si4O10(OH)2 (empirical: Na3(Mg,Li)30Si40O100(OH)20) |

| IMA symbol | Htr[1] |

| Strunz classification | 9.EC.45 |

| Crystal system | Monoclinic |

| Crystal class | Prismatic (2/m) (same H-M symbol) |

| Space group | C2/m |

| Unit cell | a = 5.25 Å, b = 9.18 Å c = 16 Å; β = 99°; Z = 2 |

| Identification | |

| Color | White, cream, pale brown, mottled |

| Crystal habit | Thin laths and aggregates |

| Cleavage | [001] Perfect |

| Fracture | Uneven |

| Mohs scale hardness | 1–2 |

| Luster | Earthy to waxy |

| Streak | White |

| Diaphaneity | Translucent to opaque |

| Specific gravity | 2–3 |

| Optical properties | Biaxial (−) – 2V small |

| Refractive index | nα = 1.490 nβ = 1.500 nγ = 1.520 |

| Birefringence | δ = 0.030 |

| References | [2][3][4] |

Hectorite is a rare soft, greasy, white clay mineral with a chemical formula of Na0.3(Mg,Li)3Si4O10(OH)2.[2]

Hectorite was first described in 1941 and named for an occurrence in the United States near Hector (in San Bernardino County, California,[4] 30 miles east of Barstow.) Hectorite occurs with bentonite as an alteration product of clinoptilolite from volcanic ash and tuff with a high glass content.[2] Hectorite is also found in the beige/brown clay ghassoul, mined in the Atlas Mountains in Morocco.[5] A large deposit of hectorite is also found at the Thacker Pass lithium deposit, located within the McDermitt Caldera in Nevada. The Thacker Pass lithium deposit could be a significant source of lithium.[6]

Despite its rarity, it is economically viable as the Hector mine sits over a large deposit of the mineral. Hectorite is mostly used in making cosmetics, but has uses in chemical and other industrial applications, and is a mineral source for refined lithium metal.[7]

See also

[edit]- Classification of minerals

- List of minerals

- Saponite – Trioctahedral phyllosilicate mineral

References

[edit]- ^ Warr, L.N. (2021). "IMA–CNMNC approved mineral symbols". Mineralogical Magazine. 85 (3): 291–320. Bibcode:2021MinM...85..291W. doi:10.1180/mgm.2021.43. S2CID 235729616.

- ^ a b c Anthony JW, Bideaux RA, Bladh KW, et al. (1995). "Hectorite" (PDF). Handbook of mineralogy. Tucson, Ariz.: Mineral Data Publishing. ISBN 9780962209734. OCLC 20759166.

- ^ "Hectorite Mineral Data". webmineral.com. Retrieved 3 Apr 2019.

- ^ a b Jololyn R (2007). "Hectorite: Mineral information, data and localities". www.mindat.org. Retrieved 3 Apr 2019.

- ^ Benhammou A, Tanouti B, Nibou L, et al. (2009). "Mineralogical and Physicochemical Investigation of Mg-Smectite from Jbel Ghassoul, Morocco". Clays and Clay Minerals. 57 (2): 264–270. Bibcode:2009CCM....57..264B. doi:10.1346/CCMN.2009.0570212. S2CID 95505225.

- ^ Bradley, Dwight C.; Stillings, Lisa L.; Jaskula, Brian W.; Munk, LeeAnn; McCauley, Andrew D. (2017). Lithium, Chapter K of Critical Mineral Resources of the United States—Economic and Environmental Geology and Prospects for Future Supply (PDF) (Report). United States Geological Survey.

- ^ Moores S (2007). "Between a rock and a salt lake". Industrial Minerals. 477: 58–69.