Heaven on Earth: Art from Islamic Lands

Illustration from the Great Mongol Shahnameh, 14th century | |

| Date | 25 March – 22 August 2004 |

|---|---|

| Venue | Somerset House, London |

| Type | Art exhibition |

| Theme | Islamic art |

Heaven on Earth: Art from Islamic Lands was an exhibition of Islamic art hosted by Somerset House in London, England from 25 March to 22 August 2004. It drew from two collections: the UK-based Khalili Collection of Islamic Art (the world's largest private collection of Islamic art) and Russia's Hermitage Museum.

The exhibition showed a range of fine and decorative art from Islamic countries, spanning more than a thousand years. The works included illuminated Quran manuscripts, paintings, metalwork, textiles, and ceramics. Critics' reviews were favourable, praising the beauty and diversity of the art on display.

Background

[edit]The Hermitage Museum in Saint Petersburg holds Russia's largest state collection of Islamic art.[1] It formed a department of the Islamic East in 1920 and, in that decade, started to run exhibitions of Islamic art.[2] From 2000 to 2007, the Hermitage Rooms at Somerset House in London were used to showcase exhibits from the museum's collections.[3][4]

The Khalili Collection of Islamic Art is one of the eight Khalili Collections assembled by the British/ Iranian scholar, collector, and philanthropist Sir David Khalili. It is the world's largest private collection of Islamic art, with 28,000 objects covering the period from 700 to 2000CE. Exhibitions entirely drawn from the collection have been held in several countries and other exhibitions have featured loaned objects.[5][6][7]

For much of its history, Islamic sacred art has been characterised by aniconism: a prohibition against depictions of living beings. Islamic cultures and time periods differed in how they interpreted this, either as applying narrowly to religious art or to art as a whole.[8][9][10] Islamic artists compensated for the restrictions on figurative art by using decorative calligraphy, geometric patterns, and stylised foliage known as arabesque.[10]

Content

[edit]The exhibition took up five rooms within the Courtauld Institute of Art, based in Somerset House, and included art from the 8th to the 19th centuries.[11] Geographically, the exhibits ranged in origin from Moorish Spain to India.[12]

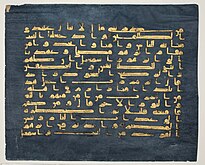

The Quran manuscripts spanned from the 8th to the 16th century, showing the evolution of Arabic script styles and the gradual increase in decorative illumination and colour. They included a folio from the 10th-century Blue Quran, which is distinctive for having gold lettering on stained blue vellum.[13]

-

Folio from the Blue Quran, 10th century North Africa or Spain

-

Quran in ink and gold Maghribi script with watercolour, North Africa, c. 1250–1350 AD

-

Mughal Quran from the second half of the 16th century

As well as earthenware and fritware bowls, the pottery included tiles decorated with calligraphy. A set of tiles from a shrine in Varamin had text with geometric patterns, including quotations from the Quran, the Persian epic Shahnameh, and the romantic poem Layla and Majnun.[14]

Although there is a traditional Muslim prohibition on making vessels out of silver or gold, it was not always obeyed, as shown by two gilt silver dishes from the 7th to 9th centuries, showing a lion attacking a bull and a prince slaying lions.[15] Other metalwork included incense burners and water vessels in animal shapes, as well as two cast brass/bronze buckets from the 12th and 13th centuries, decorated with court scenes and fantastical creatures in copper, silver, and gold.[16]

The textiles on display included phelonions (vestments) made in Ottoman Turkey for the Orthodox Church as well as prayer rugs.[17] A black satin panel, embroidered in gold and silver thread, had formed part of the hizam, the belt around the upper part of the Kaaba.[18] A 17th or 18th-century talismanic coat, decorated with the ninety-nine names of God in Islam and Quran quotations, had been made for a dervish follower of Yasawi.[19]

The paintings included Mughal miniatures, 18th- and 19th-century Persian paintings, and portraits from India and Iran.[20] Among them was Musa va 'Uj, a 15th century painting that shows Moses, Jesus, and Muhammed.[21] Many of the figural paintings were by the highly influential 17th century court miniaturist Reza Abbasi or by artists taught or influenced by him, including Mo'en Mosavver.[22]

Other media represented included glass (two mosque lamps) and stone, including a Mughal stele carved with the shahadah and the Throne Verse of the Quran.[23]

-

Stonepaste bowl decorated with red and black enamels, c. 1200 Iran

-

Emerald-set box, c. 1635 Mughal India

-

Painting of a youth in European dress by Mo'en Mosavver, 1648

-

Maharana Sangram Singh of Mewar hunting on his horse, Jambudvipa; 1720s India

In June there was a changeover in one section of the exhibition. For conservation reasons, 17 paintings from the Hermitage collection were removed from display and replaced with 26 works from the Khalili Collection. The new exhibits included five folios from the illustrated Houghton Shahnameh.[11]

Reception and legacy

[edit]

The exhibition was attended by several art critics who gave it broadly positive reviews. Peter Campbell in the London Review of Books described an exhibition that was not large but still "covers a daunting range in time and territory". He noted that most people attending the exhibition could not read the texts, but would still be able to appreciate the skill of the calligraphy.[24] For Andrew Graham-Dixon in the Sunday Telegraph, the exhibition showed common themes between Muslim and Western spirituality and culture. He described the Quran manuscript folios as "moving and beautiful objects" which suited the context of an art gallery surprisingly well.[25] For the Evening Standard, Nick Hackworth described Heaven on Earth as "the most significant exhibition of Islamic Art in London for almost three decades", praising in particular the "hypnotic beauty" of the decorated manuscript Qurans.[26]

Reviewing for The Guardian, Jonathan Jones described the objects on display as "beautiful" and advised that "Everyone should look at the art of Islam. It confounds every stereotype - including the idea that Islam is identical in every time and place." At the same time, he said that the Western practice of displaying religious objects in an art exhibition that anyone could visit could be seen as a betrayal of a cultural tradition in which religion was essential.[27] Tara Pepper in Newsweek was surprised at how much of the art was secular in nature. She described the exhibition as reconstructing "the diverse fragments of a dazzling culture".[28] The Antiques Trade Gazette said that Heaven on Earth "[packed] a wealth of history" into the five rooms and was "certainly worth seeing".[11] In the Financial Times, Jackie Wullschager described it as "a sensuous feast" that combined the opulence of secular leaders and the abstraction of Islamic religious art.[29] Andrew Lambirth in The Spectator also remarked on the contrast between luxury and austerity, describing the exhibition as a whole as fresh and coherent.[30]

Publications

[edit]A catalogue of the exhibition's 133 objects, edited by Mikhail Piotrovsky and J. M. Rogers, was published by Prestel Publishing. It includes introductory essays by Piotrovsky, Rogers, and A. A. Ivanov of the Hermitage Museum.[31]

References

[edit]- ^ Lasikova, Galina (2020), Norton-Wright, Jenny (ed.), "In Pursuit of Islamic Art in Moscow", Curating Islamic Art Worldwide: From Malacca to Manchester, Heritage Studies in the Muslim World, Cham: Springer International Publishing, pp. 83–93, doi:10.1007/978-3-030-28880-8_7, ISBN 978-3-030-28880-8, retrieved 6 December 2023

- ^ Adamova, Adel T. (July 1999). "Permanent exhibitions: a variety of approaches". Museum International. 51 (3): 5. doi:10.1111/1468-0033.00209. ISSN 1350-0775.

- ^ Ba-Isa, Molouk Y. (7 September 2004). "Islamic Art on Show in London". Arab News. Retrieved 22 January 2024.

- ^ "Hermitage to Shut London Branch". The New York Times. 20 October 2007. Retrieved 22 January 2024.

- ^ Moore, Susan (12 May 2012). "A leap of faith". Financial Times. Retrieved 6 December 2023.

- ^ "BBC World Service – Arts & Culture – Khalili Collection: Picture gallery". BBC. 14 December 2010. Retrieved 6 December 2023.

- ^ "The Eight Collections". Nasser David Khalili. Retrieved 17 June 2024.

- ^ Burckhardt, Titus (2009). Art of Islam: Language and Meaning. World Wisdom, Inc. pp. 29–31. ISBN 978-1-933316-65-9.

- ^ Allen, Terry (1988). "Aniconism and Figural Representation in Islamic Art". Five Essays on Islamic Art. Michigan: Solipsist Press. ISBN 9780944940006. OCLC 19270867. Archived from the original on 3 March 2016.

- ^ a b Esposito, John L. (2011). What Everyone Needs to Know about Islam (2nd ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 15. doi:10.1093/wentk/9780199794133.001.0001. ISBN 978-0-19-979413-3.

- ^ a b c "Heaven on Earth exhibition". Antiques Trade Gazette. 26 May 2004. Archived from the original on 28 November 2022. Retrieved 16 November 2023.

- ^ Koenig, Rhoda (23 March 2004). "Preview: Islam's heavenly treasures; Art A sensational new exhibition at Somerset House, London, reveals the wonders of Islamic art". The Independent. London. p. 18 – via Gale OneFile.

- ^ Piotrovsky & Rogers 2004, pp. 51–63.

- ^ Piotrovsky & Rogers 2004, pp. 64–67.

- ^ Piotrovsky & Rogers 2004, pp. 78–83.

- ^ Piotrovsky & Rogers 2004, pp. 85–95.

- ^ Piotrovsky & Rogers 2004, pp. 100–106.

- ^ Piotrovsky & Rogers 2004, p. 97.

- ^ Piotrovsky & Rogers 2004, pp. 48–49.

- ^ Piotrovsky & Rogers 2004, p. 5.

- ^ Piotrovsky & Rogers 2004, p. 111.

- ^ Piotrovsky & Rogers 2004, pp. 122–136.

- ^ Piotrovsky & Rogers 2004, pp. 74–77.

- ^ Campbell, Peter (6 May 2004). "At Somerset House: Islamic art". London Review of Books. Vol. 26, no. 9. ISSN 0260-9592. Retrieved 16 November 2023.

- ^ Graham-Dixon, Andrew (4 April 2004). "In the gardens of Paradise; Art". Sunday Telegraph. Retrieved 6 December 2023 – via Westlaw.

- ^ Hackworth, Nick (25 March 2004). "Linked by Muddle: Hypnotic beauty of God's mind". The Evening Standard. p. 48 – via Westlaw.

- ^ Jones, Jonathan (13 April 2004). "Arabian delights". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 16 November 2023.

- ^ Pepper, Tara (11 April 2004). "Periscope". Newsweek. Retrieved 16 November 2023.

- ^ Wullschager, Jackie (22 May 2004). "Art". Financial Times. p. 39 – via Gale OneFile.

- ^ Lambirth, Andrew (3 April 2004). "Visual edification". The Spectator. 294 (9165): 54 – via Gale OneFile.

- ^ "Heaven on earth : art from Islamic lands : works from the State Hermitage Museum and the Khalili Collection". search.worldcat.org. Retrieved 30 January 2024.

Sources

[edit]- Piotrovsky, M. B.; Rogers, J. M., eds. (2004). Heaven on Earth: Art from Islamic Lands. Prestel. ISBN 3791360132. OCLC 1022836498.

External links

[edit]- Official page on the Hermitage Rooms web site - archived as of 7 August 2011

- Official page on Khalili Collections web site

- Picture gallery hosted by the BBC, 10 August 2004