Hartford, Tennessee

Hartford, Tennessee | |

|---|---|

Businesses in Hartford | |

| Coordinates: 35°49′0″N 83°8′36″W / 35.81667°N 83.14333°W | |

| Country | United States |

| State | Tennessee |

| County | Cocke |

| Elevation | 1,263 ft (385 m) |

| Population (2000) | |

• Total | 814 |

| Time zone | UTC-5 (Eastern (EST)) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC-4 (EDT) |

| ZIP codes | 37753 |

| GNIS feature ID | 1328398[1] |

Hartford is an unincorporated community in Cocke County, Tennessee, located in the southeastern United States. Although it is not a census-designated place, the ZIP Code Tabulation Area for the ZIP Code (37753) that serves Hartford had a population of 814, according to the 2000 census.[2]

Hartford is the easternmost community in Tennessee along Interstate 40, and thus acts as the state's "gateway" by helping to maintain the Tennessee Welcome Center. The community is located at the northeastern tip of the Great Smoky Mountains and lies within the Cherokee National Forest.

Demographics

[edit]As of the census[3] of 2000, there were 814 people, 333 households, and 226 families residing in the Zip Code Tabulation Area for zip code 37753, which serves Hartford. The racial makeup of the ZCTA was 98.2% White, 0.1% Native American, 0.1% Asian, and 1.6% from two or more races. Hispanic and Latino of any race were 1.4% of the population.

There were 333 households, out of which 27.0% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 48.3% were married couples living together, 13.8% had a female householder with no husband present, and 32.1% were non-families. The average household size was 2.44 and the average family size was 2.94.

78.9% of the population was 18 years of age or older with 13.6% being 65 years of age or older. The median age was 39.9 years. The population was 53.1% male and 46.9% female.

The median income for a household in ZCTA 37753 was $20,357, and the median income for a family was $25,185. The per capita income for the ZCTA was $10,684. About 23.0% of families and 29.8% of the population were below the poverty line.

Geography

[edit]

Hartford is located at 35°49′0″N 83°8′36″W / 35.81667°N 83.14333°W (35.816670, -83.143330).[4] The community is situated in a narrow valley along the Pigeon River, which flows from its source high in the Blue Ridge Mountains down into the flatlands of Cocke County. The river's valley divides the Great Smokies crest to the southwest from the Snowbird massif to the northeast.

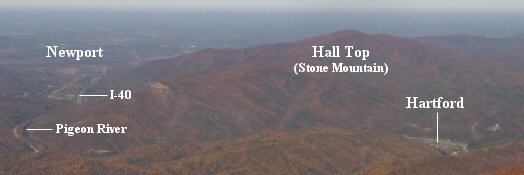

Hartford is surrounded by mountains on all sides, with Snowbird Mountain rising some 4,200 feet to the east and Mount Cammerer— the easternmost of the Great Smokies— rising nearly 5,000 feet to the south. To the west, Foothills Parkway traverses Green Mountain, connecting the Pigeon Valley to Cosby, Tennessee. Stone Mountain, commonly called Hall Top, dominates the area to the north.

Interstate 40, which passes through Hartford, follows the Pigeon River Valley between Cocke County and Haywood County, North Carolina. Along I-40, Hartford is located roughly halfway between Knoxville, Tennessee and Asheville, North Carolina.

History

[edit]

The first known permanent settler in what is now Hartford was Solomon Williams, who arrived in the area in 1853. He was followed shortly thereafter by Moses Clark, who would donate the land upon which a log meeting house was built. For much of the 19th century, this meeting house was used for various functions, including church services and school. In this period, the community was known simply as Pigeon Valley. Hartford's Pigeon Valley Church, organized in 1889, still bears the town's old name.[5]

Like many Appalachian communities, Pigeon Valley thrived during the logging boom of the late 19th century. Innovations such as the band saw and high demand for wood led lumber companies to seek out the dense forests of the Appalachian Mountains for timber. The Scottish-Carolina Timber and Land Company, which had established a foothold in the region through its American agent Alexander Arthur (1846–1912), was among the first to harvest the trees in the Pigeon Valley area, which they moved downstream via river current to the A.C. Lawrence Leather Company factory in Newport. The leather company used the trees' bark in the tanning process.[5] The Scottish Lumber venture lasted for roughly six years. In 1886, a massive flood on the Pigeon River scattered the company's stock of logs, and the company was forced to shut down operations.[6]

Early 1900s

[edit]Pigeon Valley was given the name "Hartford" in honor of John Hart, co-owner of the Tennessee & North Carolina Railroad who supervised the construction of a line through the valley connecting Newport and Waterville.

In 1917, the Boice Hardwood Company erected a band mill at Hartford with plans to log the river's north bank all the way to Max Patch Mountain. Hartford quickly developed into a company town, situated around the band mill.[7] Mary Bell Smith, who lived in Hartford during this period, recalls:

Every morning Hartford came to life at five o'clock with the shrill whistle from the sawmill that signaled the new day. Before dawn, the big steam boiler began belching out the steam which operated the sawmill for another day. The bandsaw hummed, the cut-off saw screeched, and the drag-chain rumbled as it carried trash, cull lumber, and sawdust up the conveyor to the blazing furnace.[8]

As the mill prospered in the 1920s Hartford grew to include several frame houses, a general store, a post office, a school, and a movie theater. The sawmill's generators even provided electricity to the town from 5am to 10pm.[9] Converts trickled into the old Pigeon Valley Church. Smith recalled a baptism held in Hartford in the dead of winter in 1925:

At two o'clock that Sunday afternoon, Rev. Hall walked into the Pigeon River, pushing away mushy ice as he walked. Wading far enough out into the river for the water to reach about waist high, he prepared himself for the baptismal service. We spectators watched with steamy breath from the river banks as the newly converted believers were momentarily buried in the icy waters.[10]

With the onset of the Great Depression in the early 1930s, the timber market dried up, and Boice Hardwood was forced to close.[11] Hartford wouldn't recover economically until the construction of I-40 through the town in the 1960s.[12]

The Pigeon River Pollution Controversy

[edit]

While the various lumber industries along the Pigeon River brought at least temporary prosperity to many of the valley's communities, the long-term effects of the mills' use of the river for waste dumping eventually began to take its toll.

In 1908, Champion International (then known as the Champion Fibre Company)— which had bought up large tracts of forest in the Smokies— established a paper mill in Canton, North Carolina (upstream from Hartford). Over the next few decades, Champion, like other industries along the Pigeon, used the river to dispose of its industrial waste.

Throughout the 20th century, the Pigeon River Valley experienced a relatively high rate of cancer and other toxin-related deaths. Hartford itself was hit particularly hard, earning the nickname "Widowville."[13] Environmentalists blamed the high cancer rate on the unusually high levels of dioxins and dioxin-like compounds in the tissue of fish living in the river. After it was determined that Champion's Canton mill was the primary source of the excessive dioxin levels, the Environmental Protection Agency began to pressure the paper manufacturer to reduce its dioxin emissions. The debate reached a high point in 1988, when then-Senator Al Gore— who was seeking the Democratic presidential nomination— intervened on behalf of Champion. As Gore is normally pro-environment, many saw this move as hypocritical, and accused Gore of selling out the Pigeon Valley in order to gain much-needed primary votes in North Carolina.[14]

In spite of Gore's apparent snub, pressure from environmental groups continued, and Champion began taking measures to drastically reduce dioxin emissions in the early 1990s. By 1994, Champion had spent $330 million modernizing its plant before new regulations forced the company to sell the plant in 1999.[14] Starting in 2002, the paper mill's new owner, the Blue Ridge Paper Company, spent $22 million to clean up the river. The measures taken by Champion and Blue Ridge Paper led to a 99% reduction in the river's dioxin levels, and in early 2007, state advisory boards deemed fish caught in the Pigeon River safe for consumption.[15]

Hartford today

[edit]

Along with being one of the few refueling stops along the 60-mile stretch of I-40 between Newport and Waynesville, North Carolina, Hartford has managed to take advantage of its position along a relatively rapid leg of the Pigeon River to attract whitewater rafting enthusiasts. The Martha Sundquist State Forest is located near Hartford.

Education

[edit]The only school in Hartford is Grassy Fork Elementary School, which serves students in kindergarten through eighth grade. For high school, most students will attend Cosby High School in the neighboring community of Cosby, or Cocke County High School in Newport.

References

[edit]- ^ a b U.S. Geological Survey Geographic Names Information System: Hartford, Tennessee

- ^ U.S. Department of Commerce, Bureau of the Census, "Zip Code Tabulation Area 37753 Fact Sheet." Retrieved: December 2, 2007.

- ^ "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved January 31, 2008.

- ^ "US Gazetteer files: 2010, 2000, and 1990". United States Census Bureau. February 12, 2011. Retrieved April 23, 2011.

- ^ a b Rolfe Godshalk (editor), "Hartford," Newport (Newport, Tenn.: Clifton Club, 1970), 60-62.

- ^ Rolfe Godshalk (editor), "Newport," Newport (Newport, Tenn.: Clifton Club, 1970), 35-49.

- ^ Mary Bell Smith, In the Shadow of the White Rock (Boone, N.C.: Minor's Publishing Company, 1979), 18-20.

- ^ Mary Bell Smith, In the Shadow of the White Rock (Boone, N.C.: Minor's Publishing Company, 1979), 20-21.

- ^ Mary Bell Smith, In the Shadow of the White Rock (Boone, N.C.: Minor's Publishing Company, 1979), 16-21.

- ^ Mary Bell Smith, In the Shadow of the White Rock (Boone, N.C.: Minor's Publishing Company, 1979), 16.

- ^ Mary Bell Smith, In the Shadow of the White Rock (Boone, N.C.: Minor's Publishing Company, 1979), 22.

- ^ Rolfe Godshalk (editor), "Hartford," Newport (Newport, Tenn.: Clifton Club, 1970), 62.

- ^ Rebecca Bowe, "Enviro Triumph or Dirty Bird? Local Activists Challenge Pigeon River Success Story." The Mountain Xpress, Vol. 13 no. 33 (March 14, 2007). Retrieved: September 7, 2007.

- ^ a b Robert Zelnick, "Al Gore: A Case Study Archived September 27, 2007, at the Wayback Machine." Hoover Institute Digest, 1999 no. 3. Retrieved: September 7, 2007.

- ^ "Pigeon River Fish Termed Safe To Eat." The News & Observer Publishing Company, January 12, 2007. Retrieved: September 7, 2007.

External links

[edit]- Hartford, Tennessee — Cocke County Chamber of Commerce profile