Harold Washington Cultural Center

| |

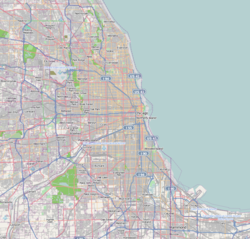

Location in South Side of Chicago | |

| Address | 4701 S. Martin Luther King Drive Chicago, Illinois 60615 |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 41°48′33.4″N 87°36′58.02″W / 41.809278°N 87.6161167°W |

| Capacity | 1,000 |

| Current use | Performing arts/business center |

| Opened | August 2004 |

| Years active | 2004–present |

| Website | |

| www | |

Harold Washington Cultural Center is a performance facility located in the historic Bronzeville neighborhood of Chicago's South Side. It was named after Chicago's first African-American Mayor Harold Washington and opened in August 2004, ten years after initial groundbreaking.[1][2] In addition to the 1,000-seat Commonwealth Edison (Com-Ed) Theatre, the center offers a Digital Media Resource Center.[3] Former Chicago City Council Alderman Dorothy Tillman and singer Lou Rawls take credit for championing the center, which cost $19.5 million.[2] It was originally to be named the Lou Rawls Cultural Center, but Alderman Tillman changed the name without telling Rawls.[2] Although it is considered part of the Bronzeville neighborhood it is not part of the Chicago Landmark Black Metropolis-Bronzeville District that is in the Douglas community area.

The limestone building, which is located on the same site as a former historic black theatre, the Regal[4] has become the subject of controversy stemming from nepotism. After a construction phase marked by delays and cost overruns, it has had a financially disappointing start and has been underutilized by many standards.[5] These disappointments were chronicled in an award winning investigative report.

The center suffered from under use leading to financial management difficulties. After it defaulted on some loans, the Chicago City Council voted in November 2010 to have the City Colleges of Chicago take over the Center and use it for a consolidated Performing Arts program.

Harold Washington

[edit]Harold Washington was a native Chicagoan who served 16 years in the Illinois Legislature and two years in the United States House of Representatives before he was elected to the mayor's office in 1983. Washington earned a B.A. in 1949 from Roosevelt University and his law degree in 1952 from Northwestern University. He was then admitted to the Illinois Bar in 1953 after which he practiced law in Chicago. His Mayoral victory encouraged Blacks throughout the country to register to vote, and marked the end of racial inequality in Chicago politics.[6]

Today

[edit]The center has not been successful by most measures. The center received $800,000 from Commonwealth Edison for the naming rights to the theatre for ten years before the center opened.[4][7] The center had originally broken ground on what was to be called the Lou Rawls Theatre and Cultural Center, in 1993 and had accepted a $100,000 check from Rawls's aunt, Vivian Carter, to help fund-raising efforts, during a second ground breaking in 1998. However, by 2002, in frustration of what should have been completed Rawls withdrew from and distanced himself from the project. Tillman insisted the delays were a function of her insistence that the project use at least 70% African-American contractors.[7] The original plan to have a Blues District surrounding the Center never materialized.[8]

Finances

[edit]The center lost nearly twice as much money as it grossed in its first full year of operations.[2] Investigative reports by the Lakefront Outlook show that between August 17, 2004 and June 30, 2005, which marked its first fiscal calendar year, the HWCC show federal tax return revenues of $678,688, including government grants of $25,000 while its expenses totaled $1,269,514.[2] It has essentially used all of the $2 million in private donations made during the construction and fund-raising phases.[2] Despite a small steady flow of public money, Tobacco Road Inc., the non-profit manager of the center has had to refinance one of the three mortgages on the property. The property did make a $50,000 profit in 2006.[9]

Calendar

[edit]Although the center was originally meant to be an education center first, and an entertainment center second it has not been a success at either.[2] Youth programming has been scarce and the performance calendar has been sparse.[2] As a result it has failed to lure the anticipated amount of tourism to the neighborhood.[10]

City takeover

[edit]On November 1, 2010, a committee of the Chicago City Council voted to invest $1.8 million in the Center and take over control of the Center as its primary lien holder for outstanding debt. By that time Tobacco Road Inc. was in loan foreclosure. The plan called for having the Center run by the City Colleges of Chicago. This was considered a way to protect the city's previous $8.9 million investment.[11] Alderman Tillman pointed out that the move was done without a proper feedback time and at a time when City Colleges finance difficulties included the Olive–Harvey College and Kennedy–King College nursing school closures. However, the plan included consolidating City Colleges performing arts programs at the center. Mayor Daley noted that the center had been "more than 200 events-a-year short of its booking obligations".[12] The City Colleges were expected to use the center for both educational and entertainment events.[13]

History

[edit]

The Center is located on a historical corner in the historical Bronzeville neighborhood. The intersection at 47th Street and Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. Drive (formerly South Park) was at one time one of the most storied intersections in the Afro-American culture. As the location of the former Regal Theatre, it played host to the most prominent icons in African-American music such as Count Basie and Duke Ellington regularly. The corner provided fodder for national gossip columnists and for the dreams of Black American youth.[4] The Bronzeville neighborhood was at one time the city's center of Black cultural, business and political life. It was also the former home to famous musicians such as Scott Joplin, Louis Armstrong, Jelly Roll Morton and Fats Waller, as well as legendary blues artist Willie Dixon and many more.[6]

Features

[edit]The Harold Washington Cultural Center has private corporate meetings rooms, to host workshops, and receptions.[3] It also has a two-story atrium equipped with three 48' plasma screens for video.[3] The center features the Com-Ed Theatre and the Digital Media Resource Center. The center is 40,000 square feet (3,700 m2) and has a statue measuring 20 feet (6.1 m) of the late Mayor at the entrance on the corner of 47th Street and Dr. Martin Luther King Drive.[14] The lobby features two-story windows that admit natural light, marble floors, a black-and-white spiral staircase, which looks like a winding piano keyboard. The Center was originally configures with an 1,800-seat theatre, an art gallery and museum space.[4]

The current Com-Ed Theatre is a 1,000 seat performance facility.[3]

The Digital Media Resource Center offers technology workshops that are free to the public. The main objective of the center is to "foster an environment that provides children and seniors of the Bronzeville community (and Chicago's south side at large) with hands on technology driven experiences." The Digital Media Resource Center is sponsored by the Illinois Institute of Technology, Comcast and Advance Computer Technical Group.[3] The state of the art center offers a wireless network with a 1 mile (1.6 km) radius. The center features Comcast broadband and has upload capability to offer online concerts from the center.[3] The computer center has 30 computer stations.[3] The center serves seniors, small business owners as well as local youth.[15]

The 750 pounds (340 kg) statue shows Mayor Washington looking authoritative in a business suit and tie and talking as if to a committee while clenching a document in his right hand and gesturing with his left. The sculpture also has a biography of Washington's political, military and academic record at the bottom.[6]

Controversy

[edit]The Lakefront Outlook, a free weekly newspaper with a circulation of 12,000 that reports on the Chicago's Bronzeville neighborhood, won a George Polk Award, one of the most coveted honors in journalism, for its investigative reports about alderman Dorothy Tillman (3rd) and the Harold Washington Cultural Center.[10] These reports focus on the post construction controversies and ignore the construction delays and cost overruns. Despite these controversies and his stand on ethics reform, U.S. Senator Barack Obama endorsed Tillman in her 2007 election in part because she was an early supporter of his.[16]

Management

[edit]Jimalita Tillman, Dorothy Tillman's daughter, is the executive director of Tobacco Road for which she is paid $45,000. Current and former members of the Tobacco Road board include her brother Bemaji Tillman; Otis Clay, a Chicago musician and long time friend of Dorothy Tillman; Robin Brown, Dorothy Tillman’s former chief of staff; Brenda Ramsey, a campaign contributor to Tillman’s 3rd Ward Democratic Organization; and Terrence Bell, a financial contributor to Tillman’s campaigns.[2]

Catering

[edit]Some of the events that the Center has hosted are under scrutiny for violating federal non-profit tax law. The Internal Revenue Service forbids persons affiliated with a non-profit group — and their relatives — from transacting for profit to a non-profit group’s senior management or members of its board of directors. Jimalita Tillman owns and operates the Spoken Word CafÈ, located directly north of the HWCC, which seems provide catering for HWCC events. That is potentially a violation of federal tax law.[2]

Events

[edit]The grand opening gala featured Roy Ayers leading a 14-piece Harold Washington Cultural Center Orchestra.[6] Among the other events hosted at the HWCC have been the Olympic Champion speedskater, Shani Davis, celebration marking his return to the United States following the 2006 Winter Olympics in March 2006.[17]

In addition, from July 23 – 25, 2006, a three-day conference commemorating the 40th anniversary of the Chicago Freedom Movement was held at the center. Attendees included C.T. Vivian and Jesse Jackson who delivered the concluding lecture.[18]

In September 2006, the Black United Fund honored Tillman and her daughters Jimalita, Ebony and Gimel at a gala at the center.[2]

The building has hosted several concerts by groups such as De La Soul,[19] and it has hosted a birthday party for Da Brat with invitees such as Mariah Carey, Jermaine Dupri and Twista.[citation needed]

In July 2009, the Center was swarmed for a viewing of the memorial of Michael Jackson.[20]

References

[edit]- ^ "Cultural center under scrutiny". Hyde Park Herald. Archived from the original on June 12, 2007. Retrieved June 6, 2007.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Meyer, Erin; Kalari Girtley. "Cultural center lost twice as much as it grossed its first year". Hyde Park Herald. Archived from the original on June 12, 2007. Retrieved June 6, 2007.

- ^ a b c d e f g "Home page". Harold Washington Cultural Center. Archived from the original on June 12, 2007. Retrieved June 6, 2007.

- ^ a b c d Henderson, Shirley (December 1, 2004). "Celebrating Harold: a new cultural center embodies the vision of former Chicago Mayor Harold Washington and helps to revitalize the community.(Harold Washington Cultural Center)". Ebony. Archived from the original on May 22, 2011. Retrieved September 25, 2007.

- ^ Manor, Robert (February 12, 2007). "EDITORIAL: For the Chicago City Council". Knight Ridder Tribune Business News. ProQuest 462753023 – via ProQuest-CSA LLC.

- ^ a b c d "Cultural Center opening, bronze statue, honor memory of Chicago's first Black mayor". Jet. September 6, 2004. Retrieved September 25, 2007.

- ^ a b Lawrence, Curtis (March 24, 2004). "Public gets first view of new cultural center". Chicago Sun-Times. Archived from the original on May 25, 2006. Retrieved September 25, 2007.

- ^ Chandler, Susan (November 17, 2007). "Retail rehab gets started on Cottage Grove: Pockets of success give hope to Bronzeville residents trying to restore commerce to once-bustling district". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved August 26, 2011.

- ^ Martin, Aratee (April 2007). "Unions, Harold Washington Center big issues in Third Ward race". Near West Gazette. Archived from the original on May 3, 2007. Retrieved September 25, 2007.

- ^ a b Manor, Robert (February 20, 2007). "Small paper honored for Bronzeville center probe". Knight Ridder Tribune Business News. ProQuest 459523901.

The staff of the Lakefront Outlook, a small free weekly newspaper that covers Chicago's Bronzeville neighborhood, on Monday won a George Polk Award, one of the most coveted honors in journalism, for stories about Ald. Dorothy Tillman (3rd) and questionable dealings at the Harold Washington Cultural Center.

- ^ Dardick, Hal (November 1, 2010). "Panel moves on city takeover of Harold Washington Cultural Center". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved August 26, 2011.

- ^ Spielman, Fran (November 1, 2010). "City Colleges get go-ahead for 'hostile takeover' of Harold Washington center". Chicago Sun-Times. Archived from the original on November 26, 2011. Retrieved August 26, 2011.

- ^ Byrne, John (October 1, 2010). "Ex-Ald. Dorothy Tillman gets another month to try to save Harold Washington center". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved August 26, 2011.

- ^ "Harold Washington Cultural Center". Metromix. Archived from the original on November 14, 2007. Retrieved September 25, 2007.

- ^ "Programs". Harold Washington Cultural Center. 2006. Archived from the original on June 14, 2007. Retrieved June 12, 2007.

- ^ Jackson, David; John McCormick (June 12, 2007). "Critics: Obama endorsements counter calls for clean government". Chicago Tribune.

- ^ Bowean, Lolly (March 26, 2006). "Davis party tour kicks off in style: Olympic champ back in Chicago for 1st time since making history". Knight Ridder Tribune Business News. ProQuest 461190133 – via ProQuest-CSA LLC.

- ^ Noel, Josh (July 24, 2006). "Activists look back, but plan for future '60s civil rights effort echoes in Chicago meeting". Knight Ridder Tribune Business News. ProQuest 463451525 – via ProQuest-CSA LLC.

The conference will wrap up Tuesday afternoon with a lecture by Rev. Jesse Jackson. On Sunday, the conference brought together activists who hadn't seen each other in decades, including Rev. C.T. Vivian, a confidant of Rev. Martin Luther King Jr.

- ^ "De La Soul". Yahoo! Events. July 6, 2004. Archived from the original on July 16, 2012. Retrieved September 25, 2007.

- ^ Ravitz, Jessica (July 7, 2011). "Michael Jackson memorialized beyond L.A." CNN. Archived from the original on March 22, 2012. Retrieved August 26, 2011.

External links

[edit]41°48′33″N 87°36′58″W / 41.809276°N 87.616117°W