Hara-Kiri: Death of a Samurai

| Hara-Kiri: Death of a Samurai | |

|---|---|

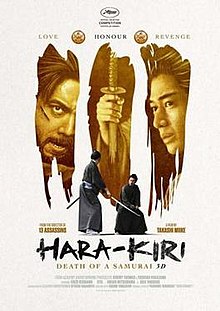

Film poster | |

| Directed by | Takashi Miike |

| Written by | Yasuhiko Takiguchi Kikumi Yamagishi |

| Based on | Harakiri by Masaki Kobayashi |

| Produced by | Toshiaki Nakazawa Jeremy Thomas |

| Starring | Ichikawa Ebizō XI Eita Kōji Yakusho |

| Cinematography | Nobuyasu Kita |

| Edited by | Kenji Yamashita |

| Music by | Ryuichi Sakamoto |

Production companies | |

| Distributed by | Shochiku (Japan) |

Release dates |

|

Running time | 126 minutes |

| Countries | Japan United Kingdom |

| Language | Japanese |

Hara-Kiri: Death of a Samurai (一命, Ichimei) is a 2011 Japanese 3D jidaigeki drama film directed by Takashi Miike. It was produced by Jeremy Thomas and Toshiaki Nakazawa, who previously teamed with Miike on his 2010 film 13 Assassins. The film is a 3D remake of Masaki Kobayashi's 1962 film Harakiri.

It premiered at the 2011 Cannes Film Festival, the first 3D film to do so.[2] The Village Voice's Michael Atkinson praised it describing it as "a melodramatic deepening and a grisly doubling-down of Kobayashi's great original".[3] Composer and pop star Ryuichi Sakamoto wrote the original score.

Plot

[edit]In 1635, Hanshiro Tsugumo's clan has lost its status and he requests permission to perform seppuku in the courtyard of the castle of Lord Ii. Senior retainer Kageyu Saitō tells Hanshiro the tale of Squire Motome Chijiiwa, another samurai from the same clan who had visited with the same request the previous year in 1634. Suspecting that he was bluffing in order to obtain money, Ii's retainers scheduled the ritual immediately with Hikokurō Omodaka acting as second. Motome begged for one more day and 3 ryō to treat his sick wife and child. His request was refused, so he began to perform seppuku ineffectively with his bamboo sword, breaking it inside his stomach. Omodaka insisted that he should cut himself more but Saitō eventually chopped off his head to end the suffering.

Saitō offers to forget the request but Hanshiro insists on continuing with the ritual. He requests Omodaka as his second, but he cannot be found. His next two requests as second, Matsuzaki and Kawabe, cannot be found either. Hanshiro tells them that in June 1617 Motome's father Jinnai Chijiiwa performed unauthorized maintenance work on the castle and was banished. He died and left Motome in the care of Hanshiro Tsugumo. In 1630, Motome married Hanshiro's daughter Miho. Her infant son fell ill and Motome sold his sword to cover costs for a while but when a doctor demanded 3 ryo in advance for treatment, Motome attempted the suicide bluff that led to his death. His son died of illness and Miho killed herself with the same broken bamboo sword after Motome's body was returned to her with 3 ryo. Disgusted at the gruesome nature of Motome's death, Hanshiro hunted down Omodaka, Matsuzaki, and Kawabe and cut off their chonmage topknots for not stopping Motome's painful death, causing them to lose face and go into hiding.

Hanshiro brings the 3 ryo back to Saitō and challenges the other samurai with a bamboo sword, battling many of them capably. He says that a warrior's honor is not something just worn for show and knocks down the castle's decorative suit of armor before accepting death. Omodaka, Matsuzaki, and Kawabe all commit seppuku out of shame and the other retainers reassemble the suit of armor. Lord Ii returns to the castle and asks if the suit of armor has been polished, because it is the pride of the castle.

Cast

[edit]- Ichikawa Ebizō XI as Hanshiro Tsugumo

- Eita as Motome Chijiiwa

- Hikari Mitsushima as Miho Tsugumo

- Naoto Takenaka as Tajiri

- Munetaka Aoki as Hikokurō Omodaka

- Hirofumi Arai as Hayatonoshō Matsuzaki

- Kazuki Namioka as Umenosuke Kawabe

- Yoshihisa Amano as Sasaki

- Takehiro Hira as Ii Kamon-no-kami Naotaka

- Takashi Sasano as Sōsuke

- Nakamura Baijaku II as Jinnai Chijiiwa

- Kōji Yakusho as Kageyu Saitō

Awards and nominations

[edit]| Award ceremony | Category | Recipients | Result |

|---|---|---|---|

| 6th Asian Film Awards | Best Original Music | Ryuichi Sakamoto | Nominated[4] |

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d Lee, Maggie (19 May 2011). "Hara-kiri: The Death of a Samurai: Cannes 2011 Review". The Hollywood Reporter. Retrieved 4 September 2017.

- ^ "Festival de Cannes: Official Selection". Cannes. Retrieved 15 April 2011.

- ^ Michael Atkinson. "Takashi Miike's Epic Hara-Kiri: Death of a Samurai Might Be His Best Film Yet". Village Voice. Retrieved 20 February 2016.

- ^ "6th Asian Film Awards". Asian Film Awards Academy. Retrieved 3 April 2023.

External links

[edit]- 2011 films

- 2010s historical drama films

- 2011 3D films

- 2011 drama films

- Japanese historical drama films

- 2010s Japanese-language films

- Remakes of Japanese films

- Japanese 3D films

- Films about suicide

- Films directed by Takashi Miike

- Films produced by Jeremy Thomas

- Films scored by Ryuichi Sakamoto

- Films set in castles

- Films set in Edo

- Films set in 1634

- Films set in 1635

- Jidaigeki films

- 2010s samurai films

- HanWay Films films

- Recorded Picture Company films

- Shochiku films

- 2010s Japanese films