Hanuman

| Hanuman | |

|---|---|

God of Wisdom, Strength, Courage, Devotion and Self-Discipline[1] | |

| Member of Chiranjivi | |

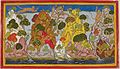

Hanuman showing Rama and Sita within his heart, illustration from Ravi Varma Press. | |

| Affiliation | Rama devotee, Deva, Chiranjivi, Vanara, avatar of Shiva (Shaivism),[2] son and avatar of Vayu (Vaishnavism).[3] |

| Abode | Kishkindha |

| Mantra | ॐ श्री हनुमते नमः (Oṁ Śrī Hanumate Namaḥ) |

| Weapon | Gada (mace) |

| Day | |

| Texts | Ramayana and its other versions Hanuman Chalisa[4] |

| Festivals | Hanuman Jayanti Diwali |

| Genealogy | |

| Parents | Vayu (spiritual father) Kesari (father) Añjanā (mother) |

| Siblings | Matiman, Shrutiman, Ketuman, Gatiman and Dhritiman (brothers) |

| Part of a series on |

| Hinduism |

|---|

|

Hanuman (/ˈhʌnʊˌmɑːn/; Sanskrit: हनुमान्, IAST: Hanumān),[5] also known as Maruti, Bajrangabali, and Anjaneya,[6] is a deity in Hinduism, revered as a divine vanara, and a devoted companion of the deity Rama. Central to the Ramayana, Hanuman is celebrated for his unwavering devotion to Rama and is considered a chiranjivi. He is traditionally believed to be the spiritual offspring of the wind deity Vayu, who is said to have played a significant role in his birth.[7][8] In Shaiva tradition, he is regarded to be an incarnation of Shiva, while in most of the Vaishnava traditions he is the son and incarnation of Vayu. His tales are recounted not only in the Ramayana but also in the Mahabharata and various Puranas.

Devotional practices centered around Hanuman were not prominent in these texts or in early archaeological evidence. His theological significance and the cultivation of a devoted following emerged roughly a millennium after the Ramayana was composed, during the second millennium CE, coinciding with the advent of Islamic rule in the Indian subcontinent.[9] Hanuman's abilities are partly attributed to his lineage from Vayu, symbolizing a connection with both the physical and the cosmic elements.[10] Figures from the Bhakti movement, such as Samarth Ramdas, have portrayed Hanuman as an emblem of nationalism and defiance against oppression.[11] According to Vaishnava tradition, the sage Madhvacharya posited that Vayu aids Vishnu in his earthly incarnations, a role akin to Hanuman's assistance to Rama.[12] In recent times, the veneration of Hanuman through iconography and temple worship has significantly increased.[13] He epitomizes the fusion of "strength, heroic initiative, and assertive excellence" with "loving, emotional devotion" to his lord Rama, embodying both Shakti and Bhakti.[14] Subsequent literature has occasionally depicted him as the patron deity of martial arts, meditation, and scholarly pursuits.[15] He is revered as an exemplar of self-control, faith, and commitment to a cause, transcending his outward Vanara appearance.[13][16][17] Traditionally, Hanuman is celebrated as a lifelong celibate, embodying the virtues of chastity.[13][18]

Various scholars have suggested that Hanuman may have influenced the conception of Sun Wukong, the central figure in the Chinese epic Journey to the West.[19][20]

Names and etymology

The meaning or origin of the word "Hanuman" is unclear. In the Hindu pantheon, deities typically have many synonymous names, each based on some noble characteristic, attribute, or reminder of a deed achieved by that deity.[21] One interpretation of "Hanuman" is "one having a disfigured jaw". This version is supported by a Puranic legend wherein infant Hanuman mistakes the Sun for a fruit, heroically attempts to reach it, and is wounded in the jaw for his attempt by Indra the King of Gods.[21]

Hanuman combines two of the most cherished traits in the Hindu bhakti-shakti worship traditions: "heroic, strong, assertive excellence" and "loving, emotional devotion to personal God".[21]

Linguistic variations of "Hanuman" include Hanumat, Anuman (Tamil), Hanumantha (Kannada), Hanumanthudu (Telugu). Other names include:

- Anjaneya,[22] Anjaniputra (Kannada), Anjaneyar (Tamil), Anjaneyudu (Telugu), Anjanisuta all meaning "the son of Anjana"

- Kesari Nandana or Kesarisuta, based on his father, which means "son of Kesari"

- Vayuputra/ Pavanputra : the son of the Vayu deva- Wind god[23]

- Vajrang Bali/Bajrang Bali, "the strong one (bali), who had limbs (anga) as hard or as tough as vajra (diamond)"; this name is widely used in rural North India[21]

- Sankata Mochana, "the remover of dangers, hardships, or hurdles" (sankata)[21]

- Māruti, "son of Maruta" (another name of Vayu deva)[24]

- Kapeeshwara, "lord of monkeys."

- Rama Doota, "the messenger (doota) of Rama"

- Mahakaya, "gigantic"

- Vira, Mahavira, "most valiant"

- Mahabala/Mahabali, "the strongest one"

- Vanarkulathin Thondaiman, "descendant of the Vanar clan" (Tamil)

- Panchavaktra, "five-faced"

- Mukhya Prana Devaru, "Primordial Life Giver" (more prominent amongst followers of Dvaita, such as Madhwas)

Historical development

Vedic roots

The earliest mention of a divine monkey is in hymn 10.86 of the Rigveda, dated to between 1500 and 1200 BCE. The twenty-three verses of the hymn are a metaphorical and riddle-filled legend. It is presented as a dialogue between multiple figures: the god Indra, his wife Indrani and an energetic monkey it refers to as Vrisakapi and his wife Kapi.[25][26][27] The hymn opens with Indrani complaining to Indra that some of the soma offerings for Indra have been allocated to the energetic and strong monkey, and the people are forgetting Indra. The king of the gods, Indra, responds by telling his wife that the living being (monkey) that bothers her is to be seen as a friend, and that they should make an effort to coexist peacefully. The hymn closes with all agreeing that they should come together in Indra's house and share the wealth of the offerings.

Epics and Puranas

Sita's scepticism

Vanaranam naranam ca

kathamasit samagamah

Translation:

How can there be a

relationship between men and monkeys?

—Valmiki's Ramayana'

Sita's first meeting with Hanuman

(Translator: Philip Lutgendorf)[28]

Hanuman is mentioned in both the Hindu epics, Ramayana and Mahabharata.[29]

Hanuman is mentioned in the Puranas.[30][31] The Shiva Purana mentions Hanuman as an avatar of Shiva; all other Puranas and scriptures clearly mention him as the spiritual son of Vayu or incarnation of Vayu or sometimes avatar of Rudra (which is also another name of Vayu).[31][32] Commonly, Hanuman is not related to Shiva in Vaishnava traditions but is known as Shiva's avatar or sun in Shaiva traditions.[33]

Other texts, such as those found in South India, present Hanuman as a being who is the union of Shiva and Vishnu, or associated with the origin of Ayyappa.[15] The 17th century Odia work Rasavinoda by Dinakrishnadasa goes on to mention that the three gods – Brahma, Vishnu and Shiva – combined to take to the form of Hanuman.[34]

Late medieval and modern era

In Valmiki's Ramayana, estimated to have been composed before or in about the 3rd century BCE,[36] Hanuman is an important, creative figure as a simian helper and messenger for Rama. It is, however, in the late medieval era that his profile evolves into a more central role and dominance as the exemplary spiritual devotee, particularly with the popular vernacular text Ramcharitmanas by Tulsidas (~ 1575 CE).[23][37] According to scholars such as Patrick Peebles and others, during a period of religious turmoil and Islamic rule of the Indian subcontinent, the Bhakti movement and devotionalism-oriented Bhakti yoga had emerged as a major trend in Hindu culture by the 16th-century, and the Ramcharitmanas presented Rama as a Vishnu avatar, supreme being and a personal god worthy of devotion, with Hanuman as the ideal loving devotee with legendary courage, strength and powers.[11][38]

During this era, Hanuman evolved and emerged as the ideal combination of shakti and bhakti.[14] Stories and folk traditions in and after the 17th century, began to reformulate and present Hanuman as a divine being, as a descendant of deities, and as an avatar of Shiva.[38] He emerged as a champion of those religiously persecuted, expressing resistance, a yogi,[39] an inspiration for martial artists and warriors,[40] a character with less fur and increasingly human, symbolizing cherished virtues and internal values, and worthy of devotion in his own right.[11][41] This evolution of Hanuman's religious status, and his cultural role as well as his iconography, continued through the colonial era and into post-colonial times.[42]

Legends

Birth

According to Hindu legends, Hanuman was born to mother Anjana and father Kesari.[15][43] Hanuman is also called the son of the deity Vayu (Wind god) because of legends associated with Vayu's role in Hanuman's birth and is said to be the incarnation of Shiva (Destroyer god). One story mentioned in Eknath's Bhavartha Ramayana (16th century CE) states that when Anjana was worshiping Vayu, the King Dasharatha of Ayodhya was also performing the ritual of Putrakameshti yagna in order to have children. As a result, he received some sacred pudding (payasam) to be shared by his three wives, leading to the births of Rama, Lakshmana, Bharata and Shatrughna. By divine ordinance, a kite snatched a fragment of that pudding and dropped it while flying over the forest where Anjana was engaged in worship. Vayu delivered the falling pudding to the outstretched hands of Anjana, who consumed it, leading to the birth of Hanuman.[43][verification needed]

Maharshi Veda Vyasa proposed Anjanadri Hill at Tirumala is the birthplace of Hanuman. Anjaneri in Nasik, Maharashtra[44][45][46] along with Anjeneri Anjanadri (Near Hampi) in Gangavathi Taluk Koppal District, Karnataka is one of a number of places that claim to be the location of Kishkinda.[47][48][49]

Childhood

According to Valmiki's Ramayana, one morning in his childhood, Hanuman was hungry and saw the sun. Mistaking it for a ripe fruit, he leapt up to eat it. In one version of the Hindu legend, the king of gods Indra intervened and struck Hanuman with his thunderbolt. It hit Hanuman on his jaw, and he fell to the earth dead with a broken jaw. Hanuman's father, Vayu, became upset and withdrew all the air from Earth. The lack of air created immense suffering to all living beings. This led Shiva to intervene and resuscitate Hanuman, which in turn prompted Vayu to return air to the living beings. As the mistake was done by the god Indra, he grants Hanuman a wish that his body would be as strong as Indra's Vajra, and that his Vajra can also not harm him. Along with Indra other gods have also granted him wishes: the God Agni granted Hanuman a wish that fire won't harm him; God Varuna granted a wish for Hanuman that water won't harm him; God Vayu granted a wish for Hanuman that he will be as fast as wind and that the wind won't harm him. Brahma also granted Hanuman a wish that he can move to any place where he cannot be stopped. Hence these wishes make Hanuman an immortal, who has unique powers and strength.[50]

In another Hindu version of his childhood legend, which is likely older and also found in Jain texts such as the 8th-century Dhurtakhyana, Hanuman's leap to the sun proves to be fatal and he is burnt to ashes from the sun's heat. His ashes fall onto the earth and oceans.[51] Gods then gather the ashes and his bones from land and, with the help of fishes, re-assemble him. They find everything except one fragment of his jawbone. His great-grandfather on his mother's side then asks Surya to restore the child to life. Surya returns him to life, but Hanuman is left with a disfigured jaw.[51] Hanuman is said to have spent his childhood in Kishkindha.

Some time after this event, Hanuman begins using his supernatural powers on innocent bystanders as simple pranks, until one day he pranks a meditating sage. In fury, the sage curses Hanuman to forget the vast majority of his powers. The curse remains into effect, until he is reminded of his powers in his adulthood.

Adulthood

Ramayana

After Rama and his brother Lakshmana, searching for Rama's kidnapped wife, Sita, arrive in Kishkindha, the new king, and Rama's newfound ally the monkey king Sugriva, agree to send scouts in all four directions to search for Rama's missing wife. To the south, Sugriva sends Hanuman and some others, including the great bear Jambavan. This group travels all the way to the southernmost tip of India, where they encounter the ocean with the island of Lanka (said to be modern day Sri Lanka) visible in the horizon. The group wishes to investigate the island, but none can swim or jump so far (it was common for such supernatural powers to be common amongst figures in these epics). However, Jambavan knows from prior events that Hanuman used to be able to do such a feat with ease and lifts his curse.[52]

The curse lifted; Hanuman now remembers all of his dynamic divine powers. He is said to have transformed into the size of mountain and flew across the narrow channel to Lanka. Upon landing, he discovers a city populated by the Lanka king Ravana and his demon followers, so he shrinks down to the size of an ant and sneaks into the city. After searching the city, he discovers Sita in a grove, guarded by demon warriors. When they all fall asleep, he meets with Sita and discusses how he came to find her. She reveals that Ravana kidnapped her and is forcing her to marry him soon. He offers to rescue her but Sita refuses, stating that her husband must do it.[52][53]

What happens next differs by account, but a common tale is that after visiting Sita, he starts destroying the grove, prompting his capture. Regardless of the tale, he ends up captured in the court of Ravana himself, who laughs when Hanuman tells him that Rama is coming to take back Sita. Ravana orders his servants to light Hanuman's tail on fire as torture for threatening his safety. However, every time they put on an oil-soaked cloth to burn, he grows his tail longer so that more cloths need to be added. This continues until Ravana has had enough and orders the lighting to begin. However, when his tail is lit, he shrinks his tail back and breaks free of his bonds with his superhuman strength. He jumps out a window and jumps from rooftop to rooftop, burning down building after building, until much of the city is ablaze. Seeing this triumph, Hanuman leaves back for India.[52][53]

When he returns, he tells his scouting party what had occurred, and they rush back to Kishkindha, where Rama had been waiting all along for news. Hearing that Sita was safe and was awaiting him, Rama gathered the support of Sugriva's army and marched for Lanka. Thus begins the legendary Battle of Lanka.[52]

Throughout the long battle, Hanuman played a role as a general in the army. During one intense fight, Lakshmana, Rama's brother, was fatally wounded; it was thought that he would die without the aid of a herb from a Himalayan mountain. Hanuman was the only one who could make the journey so quickly, and was thus sent to the mountain.

Upon arriving, he discovered that there were many herbs along the mountainside, and did not want to take the wrong herb back. So instead, he grew to the size of a mountain, ripped the mountain from the Earth, and flew it back to the battle. This act is perhaps his most legendary among Hindus.[53] A chunk of this mountain was said to have fallen down and the present day "Forts Purandar and Vajragad" are believed to be the fallen pieces.

In the end, Rama revealed his divine powers as the incarnation of the God Vishnu, and slew Ravana and the rest of the demon army. Finally, Rama returned to his home of Ayodhya to return to his place as king. After blessing all those who aided him in the battle with gifts, Rama gave Hanuman his gift, which Hanuman threw away. Many court officials, perplexed, were angered by this act. Hanuman replied that rather than needing a gift to remember Rama, he would always be in his heart. Some court officials, still upset, asked him for proof, and Hanuman tore open his chest, which had an image of Rama and Sita on his heart. Now proven as a true devotee, Rama cured him and blessed him with immortality, but Hanuman refused this and asked only for a place at Rama's feet to worship him. Touched, Rama blessed him with immortality anyway. Like Shesha Nag, Hanuman would live on after the kalpa (destruction of the universe).[52][53]

Mahabharata

Centuries after the events of the Ramayana, and during the events of the Mahabharata, Hanuman is now a nearly forgotten demigod living his life in a forest. After some time, his spiritual brother through the god Vayu, Bhima, passes through looking for flowers for his wife. Hanuman senses this and decides to teach him a lesson, as Bhima had been known to be boastful of his superhuman strength (at this point in time supernatural powers were much rarer than in the Ramayana but still seen in the Hindu epics). Bhima encountered Hanuman lying on the ground in the shape of a feeble old monkey. He asked Hanuman to move, but he would not. As stepping over an individual was considered extremely disrespectful in this time, Hanuman suggested lifting his tail up to create a passage. Bhima heartily accepted, but could not lift the tail to any avail.[54]

Bhima, humbled, realized that the frail monkey was some sort of deity, and asked him to reveal himself. Hanuman revealed himself, much to Bhima's surprise, and the brothers embraced. Hanuman prophesied that Bhima would soon be a part of a terrible war, and promised Bhima that he would sit on the flag of his brother Arjuna's chariot and shout a battle cry for Bhima that would weaken the hearts of his enemies. Content, Hanuman left his brother to his search.[citation needed]

Attributes

Hanuman has many attributes, including:

- Chiranjivi (immortal): various versions of Ramayana and Rama Katha state towards their end, just before Rama and Lakshmana die, that Hanuman is blessed to be immortal. He will be a part of humanity forever, while the story of Rama lives on and the story will go on as the gods recite the story always. Thus, he will live forever.[55]

- Brahmachari (self-controlled): one who control their lust from all materialistic things of material world.[56]

- Kurūp and Sundar: he is described in Hindu texts as kurūp (ugly) on the outside, but divinely sundar (beautiful inside).[51] The Hanuman Chalisa describes him as handsome with a complexion of molten gold (kanchana barana birāja subesā).[57]

- Kama-rupin: He can shapeshift, become smaller than the smallest, larger than the largest adversary at will.[58] He uses this attribute to shrink and enter Lanka, as he searches for the kidnapped Sita imprisoned in Lanka. Later on, he takes on the size of a mountain, blazing with radiance, to show his true power to Sita.[59]

- Strength: Hanuman is extraordinarily strong, one capable of lifting and carrying any burden for a cause. He is called Vira, Mahavira, Mahabala and other names signifying this attribute of his. During the epic war between Rama and Ravana, Rama's brother Lakshmana is wounded. He can only be healed and his death prevented by a herb found in a particular Himalayan mountain. Hanuman leaps and finds the mountain. There, states Ramayana, Hanuman finds the mountain is full of many herbs. He doesn't know which one to take. So, he lifts the entire Himalayan mountain and carries it across India to Lanka for Lakshmana. His immense strength thus helps Lakshmana recover from his wound.[60] This legend is the popular basis for the iconography where he is shown flying and carrying a mountain on his palm.[61]

- Innovative: Hanuman is described as someone who constantly faces very difficult odds, where the adversary or circumstances threaten his mission with certain defeat and his very existence. Yet he finds an innovative way to turn the odds. For example, after he finds Sita, delivers Rama's message, and persuades her that he is indeed Rama's true messenger, he is discovered by the prison guards. They arrest Hanuman, and under Ravana's orders take him to a public execution. There, Ravana's guards begin his torture by tying his tail with oiled cloth and setting it on fire. Hanuman then leaps from one palace rooftop to another, burning everything down in the process.[62]

- Bhakti: Hanuman is presented as the exemplary devotee (bhakta) of Rama and Sita. The Hindu texts such as the Bhagavata Purana, the Bhakta Mala, the Ananda Ramayana and the Ramacharitmanas present him as someone who is talented, strong, brave and spiritually devoted to Rama.[63] The Rama stories such as the Ramayana and the Ramacharitmanas, in turn themselves, present the Hindu dharmic concept of the ideal, virtuous and compassionate man (Rama) and woman (Sita) thereby providing the context for attributes assigned therein for Hanuman.[64][65]

- Learned Yogi: In the late medieval texts and thereafter, such as those by Tulasidas, attributes of Hanuman include learned in Vedanta philosophy of Hinduism, the Vedas, a poet, a polymath, a grammarian, a singer and musician par excellence.[63][15]

- Remover of obstacles: in devotional literature, Hanuman is the remover of difficulties.[63]

- Healer of diseases, pains and sorrows: Heals all kinds of diseases, pains and sorrows of devotees.

- Slayer of demons, evil and negative energies: Hanuman is offered worship to rid of negative influences, such as ghosts, evil spirits and ill-intentioned humans.[66] The following names of Hanuman describe some of these qualities, Rakshovidhwansakaraka, Akshahantre, Dashagreevakulantaka, Lankineebhanjana, Simhikaprana Bhanjana, Maharavanamardana, Kalanemi Pramathana.

- Protector and saviour of devotees of Shri Ram and himself: The doorkeeper and protector of the door to Rama's court, and protector and saviour of devotees.

- Five-faced or Panchamukha when he assumes his fierce form: East facing Hanuman face (Anjaneya) that grants purity of mind and success. South facing man-lion face Narasimha that West facing Garuda face, north facing Boar face Varaha and horse face (Hayagriva) facing towards the sky (upwards).[67]

Texts

Hinduism

Ramayana

The Sundara Kanda, the fifth book in the Ramayana, focuses on Hanuman. Hanuman meets Rama in the last year of the latter's 14-year exile, after the demon king Ravana had kidnapped Sita. With his brother Lakshmana, Rama is searching for his wife Sita. This, and related Rama legends are the most extensive stories about Hanuman.[68][69]

Numerous versions of the Ramayana exist within India. These present variant legends of Hanuman, Rama, Sita, Lakshamana and Ravana. The figures and their descriptions vary, in some cases quite significantly.[70]

Mahabharata

The Mahabharata is another major epic which has a short mention of Hanuman. In Book 3, the Vana Parva of the Mahabharata, he is presented as a half-brother of Bhima, who meets him accidentally on his way to Mount Kailasha. A man of extraordinary strength, Bhima is unable to move Hanuman's tail, making him realize and acknowledge the strength of Hanuman. This story attests to the ancient chronology of Hanuman. It is also a part of artwork and reliefs such as those at the Vijayanagara ruins.[71][72]

Other literature

Apart from Ramayana and Mahabharata, Hanuman is mentioned in several other texts. Some of these stories add to his adventures mentioned in the earlier epics, while others tell alternative stories of his life. The Skanda Purana mentions Hanuman in Rameswaram.[73]

In a South Indian version of Shiva Purana, Hanuman is described as the son of Shiva and Mohini (the female avatar of Vishnu), or alternatively he has been linked to or merged with the origin of Swami Ayyappa who is popular in parts of South India.[15]

The Muktikā Upanishad is part of a dialogue between Rama and Hanuman dealing with the inquiry into mukti.[74]

Hanuman Chalisa

The 16th-century Indian poet Tulsidas wrote Hanuman Chalisa, a devotional song dedicated to Hanuman. He claimed to have visions where he met face to face with Hanuman. Based on these meetings, he wrote Ramcharitmanas, an Awadhi language version of Ramayana.[75]

Relation with Devi or Shakti

The relation between Hanuman and the goddess Kali finds mention in the Krittivasi Ramayana. Their meeting takes place in the Yuddha Kanda of this Ramayana, in the legend of Mahiravana. Mahiravana is stated to be the king of the Patala (netherworld) and a trusted friend/brother of Ravana. After his son, Indrajita, was killed, Ravana sought Mahiravana's help to kill Rama and Lakshmana. One night, Mahiravana, using his maya, took Vibhishana's form and entered Rama's camp. He cast the nidra mantra (sleeping spell) on the vanara army, kidnapped Rama and Lakshmana, and took them to Patala to sacrifice them to Devi, as per Ravana's suggestion. Hanuman learnt the way to Patala from Vibhishana and made haste to rescue his lords. On his journey, he met Makardhwaja, who claimed of being Hanuman's son. Hanuman defeated and tied him, and went inside the palace. He met Chandrasena, who told about the sacrifice and the way to kill Mahiravana. Hanuman shrunk his size to that of a bee and came across a huge idol of Kali. After being prayed to, the goddess agreed to help Hanuman rescue the brothers, allowing him to take her place while she slipped below. When Mahiravana asked the brothers to bow, they refused, claiming not to know how to perform the act. As Mahiravana decided to demonstrate, Hanuman assumed his panchamukha (five-faced) form (manifesting the additional heads of Garuda, Narasimha, Varaha, and Hayagriva), blowing the five oil lamps present in the chamber in the five cardinal directions. He severed the head of Mahiravana, thus killing him. He carried Rama and Lakshmana upon his shoulders to return them to their camp, before which he released and crowned Makaradhvaja the king of Patala. The story of Ahiravan finds its place in the Ramayanas of the east. It can be found in the Bengali version of the Ramayana, written by Krittibash, in the passage known as Mahirabonerpala. It is believed that Kali, pleased with Hanuman, blessed him to be her dvarapala (gatekeeper).[76]

Buddhism

Hanuman appears in Tibetan Buddhism (southwest China) and Khotanese (west China, central Asia and northern Iran) versions of Ramayana. The Khotanese versions have a Jātaka tales-like theme but are generally similar to the Hindu texts in the storyline of Hanuman. The Tibetan version is more embellished, and without attempts to reference the Jātakas. Also, in the Tibetan version, novel elements appear such as Hanuman carrying love letters between Rama and Sita, in addition to the Hindu version wherein Rama sends the wedding ring with him as a message to Sita. Further, in the Tibetan version, Rama chides Hanuman for not corresponding with him through letters more often, implying that the monkey-messenger and warrior is a learned being who can read and write.[77][78]

In the Sri Lankan versions of Ramayana, which are titled after Ravana, the story is less melodramatic than the Indian stories. Many of the legends recounting Hanuman's bravery and innovative ability are found in the Sinhala versions. The stories in which the figures are involved have Buddhist themes, and lack the embedded ethics and values structure according to Hindu dharma.[81] According to Hera Walker, some Sinhalese communities seek the aid of Hanuman through prayers to his mother.[82] In Chinese Buddhist texts, states Arthur Cotterall, myths mention the meeting of the Buddha with Hanuman, as well as Hanuman's great triumphs.[83] According to Rosalind Lefeber, the arrival of Hanuman in East Asian Buddhist texts may trace its roots to the translation of the Ramayana into Chinese and Tibetan in the 6th-century CE.[84]

In both China and Japan, much like in India, there is a lack of a radical divide between humans and animals, with all living beings and nature assumed to be related to humans. There is no exaltation of humans over animals or nature, unlike the Western traditions. A divine monkey has been a part of the historic literature and culture of China and Japan, possibly influenced by the close cultural contact through Buddhist monks and pilgrimage to India over two millennia.[79] For example, the Japanese text Keiranshuyoshu, while presenting its mythology about a divine monkey, that is the theriomorphic Shinto emblem of Hie shrines, describes a flying white monkey that carries a mountain from India to China, then from China to Japan.[85] This story is based on a passage in the Ramayana where the wounded hero asks Hanuman to bring a certain herbal medicine from the Himalayas. As Hanuman does not know the herb he brings the entire mountain for the hero to choose from. By that time a learned medicine man from Lanka discovered the cure and Hanuman brings the mountain back to where he got it from. Many Japanese Shinto shrines and village boundaries, dated from the 8th to the 14th centuries, feature a monkey deity as guardian or intermediary between humans and gods (kami).[79][80]

The Jātaka tales contain Hanuman-like stories.[86] For example, the Buddha is described as a monkey-king in one of his earlier births in the Mahakapi Jātaka, wherein he as a compassionate monkey suffers and is abused, but who nevertheless continues to follow dharma in helping a human being who is lost and in danger.[87][88]

Jainism

Paumacariya (also known as Pauma Chariu or Padmacharit), the Jain version of Ramayana written by Vimalasuri, mentions Hanuman not as a divine monkey, but as a Vidyadhara (a supernatural being, demigod in Jain cosmology). He is the son of Pavangati (wind deity) and Anjana Sundari. Anjana gives birth to Hanuman in a forest cave, after being banished by her in-laws. Her maternal uncle rescues her from the forest; while boarding his vimana, Anjana accidentally drops her baby on a rock. However, the baby remains uninjured while the rock is shattered. The baby is raised in Hanuruha, thus receiving the name "Hanuman."

There are major differences from the Hindu text: Hanuman is a supernatural being in Jain texts, Rama is a pious Jaina who never kills anyone, and it is Lakshamana who kills Ravana. Hanuman becomes a supporter of Rama after meeting him and learning about Sita's kidnapping by Ravana. He goes to Lanka on Rama's behalf but is unable to convince Ravana to give up Sita. Ultimately, he joins Rama in the war against Ravana and performs several heroic deeds.

Later Jain texts, such as Uttarapurana (9th century CE) by Gunabhadra and Anjana-Pavananjaya (12th century CE), tell the same story.

In several versions of the Jain Ramayana story, there are passages that explain the connection of Hanuman and Rama (called Pauma in Jainism). Hanuman, in these versions, ultimately renounces all social life to become a Jain ascetic.[24]

Sikhism

In Sikhism, the Hindu god Rama has been referred to as Sri Ram Chandar, and the story of Hanuman as a siddha has been influential. After the birth of the martial Sikh Khalsa movement in 1699, during the 18th and 19th centuries, Hanuman was an inspiration and object of reverence by the Khalsa.[citation needed] Some Khalsa regiments brought along the Hanuman image to the battleground. The Sikh texts such as Hanuman Natak composed by Hirda Ram Bhalla, and Das Gur Katha by Kavi Kankan describe the heroic deeds of Hanuman.[89] According to Louis Fenech, the Sikh tradition states that Guru Gobind Singh was a fond reader of the Hanuman Natak text.[citation needed]

During the colonial era, in Sikh seminaries in what is now Pakistan, Sikh teachers were called bhai, and they were required to study the Hanuman Natak, the Hanuman story containing Ramcharitmanas and other texts, all of which were available in Gurmukhi script.[90]

Bhagat Kabir, a prominent writer of the scripture explicitly states that Hanuman does not know the full glory of the divine. This statement is in the context of the Divine as being unlimited and ever expanding. Ananta is therefore a name of the divine. In Sanskrit, anta means "end". The prefix -an is added to create the word Ananta (meaning "without end" or "unlimited").

ਹਨੂਮਾਨ ਸਰਿ ਗਰੁੜ ਸਮਾਨਾਂ

Hanūmān sar garuṛ samānāʼn.

Beings like Hanumaan, Garura,

ਸੁਰਪਤਿ ਨਰਪਤਿ ਨਹੀ ਗੁਨ ਜਾਨਾਂ Surpaṯ narpaṯ nahī gun jānāʼn.

Indra the King of the gods and the rulers of humans – none of them know Your Glories, Lord.

— Sri Guru Granth Sahib page 691

Southeast Asian texts

There exist non-Indian versions of the Ramayana, such as the Thai Ramakien. According to these versions of the Ramayana, Macchanu is the son of Hanuman borne by Suvannamaccha, daughter of Ravana.

Another legend says that a demigod named Matsyaraja (also known as Makardhwaja or Matsyagarbha) claimed to be his son. Matsyaraja's birth is explained as follows: a fish (matsya) was impregnated by the drops of Hanuman's sweat, while he was bathing in the ocean.[31]

Hanuman in southeast Asian texts differs from the north Indian Hindu version in various ways in the Burmese Ramayana, such as Rama Yagan, Alaung Rama Thagyin (in the Arakanese dialect), Rama Vatthu and Rama Thagyin, the Malay Ramayana, such as Hikayat Sri Rama and Hikayat Maharaja Ravana, and the Thai Ramayana, such as Ramakien. However, in some cases, the aspects of the story are similar to Hindu versions and Buddhist versions of Ramayana found elsewhere on the Indian subcontinent.

Significance and influence

Hanuman became more important in the medieval period and came to be portrayed as the ideal devotee (bhakta) of Rama.[31] Hanuman's life, devotion, and strength inspired wrestlers in India.[91]

Devotionalism to Hanuman and his theological significance emerged long after the composition of the Ramayana, in the 2nd millennium CE. His prominence grew after the arrival of Islamic rule in the Indian subcontinent.[9] He is viewed as the ideal combination of shakti ("strength, heroic initiative and assertive excellence") and bhakti ("loving, emotional devotion to his personal god Rama").[14] Beyond wrestlers, he has been the patron god of other martial arts. He is stated to be a gifted grammarian, meditating yogi and diligent scholar. He exemplifies the human excellences of temperance, faith and service to a cause.[13][16][17]

In 17th-century north and western regions of India, Hanuman emerged as an expression of resistance and dedication against Islamic persecution. For example, the bhakti poet-saint Ramdas presented Hanuman as a symbol of Marathi nationalism and resistance to Mughal Empire.[11]

Hanuman in the colonial and post-colonial era has been a cultural icon, as a symbolic ideal combination of shakti and bhakti, as a right of Hindu people to express and pursue their forms of spirituality and religious beliefs (dharma).[14][93] Political and religious organizations have named themselves after him or his synonyms such as Bajrang.[94][95][96] Political parades or religious processions have featured men dressed up as Hanuman, along with women dressed up as gopis (milkmaids) of god Krishna, as an expression of their pride and right to their heritage, culture and religious beliefs.[97][98] According to some scholars, the Hanuman-linked youth organizations have tended to have a paramilitary wing and have opposed other religions, with a mission of resisting the "evil eyes of Islam, Christianity and Communism", or as a symbol of Hindu nationalism.[99][100]

Iconography

The earliest known sculptures of Hanuman date from the Gupta Empire ca. 500 CE. In these very early representations, Hanuman is not yet shown as a sole figure. Free standing murtis or statues of Hanuman appeared from ca. 700 CE. onwards. These murtis portrayed Hanuman with one hand raised, one foot suppressing a demon, and an erect tail. [103] In later centuries his raised hand was sometimes shown supporting a mountain of healing herbs.[104]

Hanuman's iconography is derived from Valmiki's Ramayana. He is usually portrayed with other central figures of the Ramayana – Rama, Sita and Lakshmana. He carries weapons such as a gada (mace) and thunderbolt (vajra).[15][105]

His iconography and temples are common today. He is typically shown with Rama, Sita and Lakshmana, near or in Vaishnavism temples, as well as by himself usually opening his chest to symbolically show images of Rama and Sita near his heart. He is also popular among the followers of Shaivism.[13]

In north India, an iconic representation of Hanuman such as a round stone has been in use by yogis, as a means to help focus on the abstract aspects of him.[106]

Temples and shrines

Hanuman is often worshipped along with Rama and Sita of Vaishnavism, and sometimes independently of them.[23] There are numerous statues to celebrate or temples to worship Hanuman all over India. Vanamali says, "Vaishnavites or followers of Vishnu, believe that the wind god Vayu underwent three incarnations to help Vishnu. As Hanuman he helped Rama, as Bhima, he assisted Krishna, and as Madhvacharya (1238–1317) he founded the Vaishnava sect called Dvaita".[107] Shaivites claim him as an avatar of Shiva.[23] Lutgendorf writes, "The later identification of Hanuman as one of the eleven rudras may reflect a Shaiva sectarian claim on an increasing popular god, it also suggests his kinship with, and hence potential control over, a class of awesome and ambivalent deities". Lutgendorf also writes, "Other skills in Hanuman's resume also seem to derive in part from his windy patrimony, reflecting Vayu's role in both body and cosmos".[12] According to a review by Lutgendorf, some scholars state that the earliest Hanuman murtis appeared in the 8th century, but verifiable evidence of Hanuman images and inscriptions appear in the 10th century in Indian monasteries in central and north India.[108]

Tuesday and Saturday of every week are particularly popular days at Hanuman temples. Some people keep a partial or full fast on either of those two days and remember Hanuman and the theology he represents to them.[109]

Major temples and shrines of Hanuman include:

- The oldest known independent Hanuman temple and statue is at Khajuraho, dated to about 922 CE from the Khajuraho Hanuman inscription.[110][111]

- Hanumangarhi, Ayodhya, is a 10th-century temple dedicated to Hanuman.[112]

- Panchmukhi Hanuman Temple is a 1,500-year-old temple in Pakistan. It is located in Soldier Bazaar in Karachi, Pakistan. The temple is highly venerated by Pakistani Hindus as it is the only temple in the world which has a natural statue of Hanuman that is not man-made (Swayambhu).[113][114]

- Jakhu temple in Shimla, Himachal Pradesh contains a monumental 108-foot (33-metre) statue of Hanuman and is the highest point in Shimla.[115]

- The tallest Hanuman statue is the Veera Abhaya Anjaneya Swami, standing 135 feet tall at Paritala, 32 km from Vijayawada in Andhra Pradesh, installed in 2003.[116]

- Chitrakoot in Madhya Pradesh features the Hanuman Dhara temple, which features a panchmukhi statue of Hanuman. It is located inside a forest, and it along with Ramghat that is a few kilometers away, are significant Hindu pilgrimage sites.[117]

- The Peshwa era rulers in 18th century city of Pune provided endowments to more Hanuman temples than to temples of other deities such as Shiva, Ganesh or Vitthal. Even in present time there are more Hanuman temples in the city and the district than of other deities.[118]

- One of the major temples of Hanuman is Hanuman Temple Salangpur in based in Salangpur, Gujarat.[119] There is also a statue of Hanuman which is 54 ft tall.[120]

- Outside India, a major Hanuman statue has been built by Tamil Hindus near the Batu caves in Malaysia, and an 85-foot (26 m) Karya Siddhi Hanuman statue by colonial era Hindu indentured workers' descendants at Carapichaima in Trinidad and Tobago. Another Karya Siddhi Hanuman Temple has been built in Frisco, Texas in the United States.[121] In 2024, another Hanuman statue was inaugurated in Texas with the name Statue of Union, which is now the third-tallest statue in the US.[122]

Festivals and celebrations

Hanuman is a central figure in the annual Ramlila celebrations in India, and seasonal dramatic arts in southeast Asia, particularly in Thailand; and Bali and Java, Indonesia. Ramlila is a dramatic folk re-enactment of the life of Rama according to the ancient Hindu epic Ramayana or secondary literature based on it such as the Ramcharitmanas.[56] It particularly refers to the thousands[123] of dramatic plays and dance events that are staged during the annual autumn festival of Navratri in India.[124] Hanuman is featured in many parts of the folk-enacted play of the legendary war between Good and Evil, with the celebrations climaxing in Vijayadashami.[125][126]

The Ramlila festivities were declared by UNESCO as one of the "Intangible Cultural Heritages of Humanity" in 2008. Ramlila is particularly notable in the historically important Hindu cities of Ayodhya, Varanasi, Vrindavan, Almora, Satna and Madhubani – cities in Uttar Pradesh, Uttarakhand, Bihar and Madhya Pradesh.[125]

Hanuman's birthday is observed by some Hindus as Hanuman Jayanti. It falls in much of India in the traditional month of Chaitra in the lunisolar Hindu calendar, which overlaps with March and April. However, in parts of Kerala and Tamil Nadu, Hanuman Jayanti is observed in the regional Hindu month of Mārgaḻi, which overlaps with December and January. The festive day is observed with devotees gathering at Hanuman temples before sunrise, and day long spiritual recitations and story reading about the victory of good over evil.[8]

Hanuman in Southeast Asia

Cambodia

Hanuman is a revered heroic figure in Khmer history in southeast Asia. He features predominantly in the Reamker, a Cambodian epic poem, based on the Sanskrit Itihasa Ramayana epic.[127] Intricate carvings on the walls of Angkor Wat depict scenes from the Ramayana including those of Hanuman.[128]

In Cambodia and many other parts of southeast Asia, mask dance and shadow theatre arts celebrate Hanuman with Ream (same as Rama of India). Hanuman is represented by a white mask.[129][130] Particularly popular in southeast Asian theatre are Hanuman's accomplishments as a martial artist Ramayana.[131]

Indonesia

Hanuman (Indonesian: Hanoman or Anoman ) is the central figure in many of the historic dance and drama art works such as Wayang Wong found in Javanese culture, Indonesia. These performance arts can be traced to at least the 10th century.[132] He has been popular, along with the local versions of Ramayana in other islands of Indonesia such as Java.[133][134]

In major medieval era Hindu temples, archeological sites and manuscripts discovered in Indonesian and Malay islands, Hanuman features prominently along with Rama, Sita, Lakshmana, Vishvamitra and Sugriva.[135][136] The most studied and detailed relief artworks are found in the Candis Panataran and Prambanan.[137][138]

Hanuman, along with other figures of the Ramayana, are an important source of plays and dance theatre repertoire at Odalan celebrations and other festivals in Bali.[139]

Wayang story

Hanoman in Javanese wayang is the son of Batara Guru who became the disciple and adopted son of Batara Bayu. Hanoman himself is a cross-generational figure from the time of Rama to the time of Jayabaya. Anjani is the eldest daughter of Rishi Gotama who is cursed so that she has the face of an ape. On the orders of his father, he was imprisoned naked in the lake Madirda. Once upon a time, Batara Guru and Batara Narada flew across the sky. When he saw Anjani, Batara Guru was so amazed that he released semen. The king of the puppet gods rubbed it with tamarind leaves and threw it into the lake. The sinom leaf fell on Anjani's lap. She also picked it up and ate it until she became pregnant. When it was time to give birth, Anjani was assisted by the angels sent by Batara Guru. She gave birth to a baby monkey with white hair, while herself again had a beautiful face and was taken to heaven as an angel.

The baby, in the form of a white monkey, which is Anjani's son, was taken by Batara Bayu and adopted as a child. After completing his education, Hanoman returned to the world and served his uncle, Sugriwa, the monkey king of Kiskenda Cave. At that time, Sugriwa had just been defeated by his brother, Subali, another uncle of Hanoman. Hanoman managed to meet Rama and Laksmana, a pair of princes from Ayodhya who were undergoing exile. The two then work together with Sugriwa to defeat Subali, and together attack the land of Alengka to free Sita, Rama's wife who was kidnapped by Rahwana, Subali's disciple.

Hanoman infiltrates the Alengka palace to investigate Ravana's power and witness Sita's plight. There he made such a mess that he was caught and burned. Instead, Hanoman actually managed to burn parts of the capital city of Alengka. This event is known as Hanuman Obong. After Hanoman returned to Rama's place, the monkey army set out to attack Alengka. Hanoman appears as a hero who kills many Alengka troops, for example Surpanaka (Sarpakenaka) Ravana's younger brother. In the final battle between Rama and Ravana, he was overwhelmed with his Aji Pancasu, the ability to live eternally. Every time Rama's weapon killed Ravana, immediately Ravana rose again. Wibisana, Ravana's sister who sided with Rama immediately asked Hanoman to help. Hanoman also lifted Mount Ungaran to fall on top of Ravana's corpse when Ravana had just died at the hands of Rama for the umpteenth time. Seeing Hanuman's impudence, Rama also punished him to guard Ravana's grave. Rama believes that Ravana is still alive under the crush of the mountain, and at any time can release his spirit to wreak havoc in the world.

Several years later after Rama died, Ravana's spirit escaped from Mount Pati and went to Sumatra Island to seek the reincarnation of Sita, namely Subhadra, Krishna's sister. Krishna himself is the reincarnation of Rama. Hanoman chases and meets Bima, his younger brother and Bayu's adopted son. Hanuman then served Krishna. He also managed to capture the spirit of Ravana and imprisoned him in Mount Kendalisada. On the mountain Hanoman acts as a hermit.

Unlike the original version, Hanoman in the wayang has two children. The first is named Trigangga who is in the form of a white ape like himself. It is said that when he came home from burning Alengka, Hanoman had the image of Trijata's face, Wibisana's daughter, who took care of Sita. Over the ocean, Hanuman's semen fell and caused the seawater to boil. Unbeknownst to him, Baruna created the foam into Trigangga. Trigangga immediately grew up and met Bukbis, the son of Ravana. The two are friends and sided with Alengka against Rama. In the war Trigangga managed to kidnap Rama and Laksmana but was chased by Hanoman. Narada came down to intervene and explained the blood relationship between the two white monkeys. Finally, Trigangga turned against Ravana.

Hanuman's second son was named Purwaganti, who had only appeared in the Pandavas era. He was credited with finding Yudhisthira's lost heirloom named Kalimasada. Purwaganti was born to a priest's daughter whom Hanoman married, named Purwati. Hanuman lived so long that he was tired of living. Narada descends to grant his wish, which is to die, as long as he can complete the final task, which is to reconcile the six descendants of Arjuna who are involved in a civil war. Hanoman disguised himself as Resi Mayangkara and succeeded in marrying Astradarma, son of Sariwahana, to Pramesti, daughter of Jayabaya. The Sariwahana family and Jayabaya were involved in a dispute even though they were both descendants of Arjuna. Hanoman then appeared to face Jayabaya's enemy named Yaksadewa, the king of Selahuma. In that war, Hanuman died, moksha with his body, while Yaksadewa returned to his original form, namely Batara Kala, the god of death.[140]

Thailand

Hanuman plays a significantly more prominent role in the Ramakien.[142] In contrast to the strict devoted lifestyle to Rama of his Indian counterpart, Hanuman is known in Thailand as a promiscuous and flirtatious figure.[143] One famous episode of the Ramakien has him fall in love with the mermaid Suvannamaccha and fathering Macchanu with her. In another, Hanuman takes on the form of Ravana and sleeps with Mandodari, Ravana's consort, thus destroying her chastity, which was the last protection for Ravana's life.[144]

As in the Indian tradition, Hanuman is the patron of martial arts and an example of courage, fortitude and excellence in Thailand.[145] He is depicted as wearing a crown on his head and armor. He is depicted as an albino with a strong character, open mouth, and sometimes is shown carrying a trident.

Hanuman is the mascot of the 1st Asian Martial Arts Games in Bangkok, Thailand.

Lineage

Though Hanuman is described to be celibate in the Ramayana and most of the Puranas, according to some regional sources, Hanuman married Suvarchala, the daughter of Surya (Sun-God).[146]

However, once Hanuman was flying above the seas to go to Lanka, a drop of his sweat fell in the mouth of a crocodile, which eventually turned into a baby. The monkey baby was delivered by the crocodile, who was soon retrieved by Ahiravana, and raised by him, named Makardhwaja, and made the guard of the gates of Patala, the former's kingdom. One day, Hanuman, when going to save Rama and Lakshmana from Ahiravana, faced Makardhwaja and defeated him in combat. Later, after knowing the reality and after saving him, he made his son the king of Patala.

The Jethwa clan claims to be a descendant of Makardhwaja, and, according to them, he had a son named Modh-dhwaja, who in turn had a son named Jeth-dhwaja, hence the name of the clan.

In popular culture

While Hanuman is a quintessential character of any movie on Ramayana, Hanuman-centric movies have also been produced with Hanuman as the central character. In 1976 the first biopic movie on Hanuman in Hindi was released with wrestler Dara Singh playing the role of Hanuman. He again reprised the character in Ramanand Sagar's television series Ramayan and B. R. Chopra's Mahabharat.[147] The TV series Jai Hanuman was released in 1997 on Doordarshan.

In 2005 an animated movie of the same name was released and was extremely popular among children. Actor Mukesh Khanna voiced the character of Hanuman in the film.[148] Following this several series of movies featuring the god were produced, though all of them were animated, prominent ones being the Bal Hanuman series 2006–2012. Another movie, Maruti Mera dost, (2009) was a contemporary adaptation of Hanuman in modern times.[149]

The 2015 Bollywood movie Bajrangi Bhaijaan had Salman Khan playing the role of Pawan Kumar Chaturvedi, who is an ardent Hanuman devotee and regularly invokes him for his protection, courage, and strength.[150]

US president Barack Obama had a habit of carrying with him a few small items given to him by people he had met. The items included a small figurine of Hanuman.[151][152]

Hanuman was referenced in the 2018 Marvel Cinematic Universe film, Black Panther and its 2022 sequel Black Panther: Wakanda Forever, which are set in the fictional African nation of Wakanda; the Jabari tribe often is seen saying Glory to "Hanuman" as the tribe worships its ancestral gorilla deity. The reference was removed from the film in theatre screenings in India. But the uncensored part came out later on digital streaming platforms in the country.[153][154]

The Mexican acoustic-metal duo, Rodrigo Y Gabriela released a hit single named "Hanuman" from their album 11:11. Each song on the album was made to pay tribute to a different musician that inspired the band, and the song Hanuman is dedicated to Carlos Santana. Why the band used the name Hanuman is unclear, but the artists have stated that Santana "was a role model for musicians back in Mexico that it was possible to do great music and be an international musician."[155]

Hanuman is the protagonist in the 2022 film Hanuman White Monkey, a fantasy film that combines special effects with a Khon (Thai masked pantomime) performance style.[156] In the 2022 action-adventure Ram Setu, it is implied that the character "AP" is actually Hanuman.[157] In 2024, Telugu film director Prasanth Varma directed the film Hanu-Man, a superhero film based on Hanuman's power. The film's sequel, Jai Hanuman, is set to be released during the Sankranti of 2025 and would directly show Hanuman keeping his promise to Rama.

Literature

The Sapta Chiranjivi Stotram is a mantra that is featured in Hindu literature:

अश्वत्थामा बलिर्व्यासो हनुमांश्च विभीषण:।

कृप: परशुरामश्च सप्तैतै चिरञ्जीविन:॥

सप्तैतान् संस्मरेन्नित्यं मार्कण्डेयमथाष्टमम्।

जीवेद्वर्षशतं सोपि सर्वव्याधिविवर्जितः॥ aśvatthāmā balirvyāsō hanumāṁśca vibhīṣaṇaḥ।

kṛpaḥ paraśurāmaśca saptaitai cirañjīvinaḥ॥

saptaitān saṁsmarēnnityaṁ mārkaṇḍēyamathāṣṭamam।

jīvēdvarṣaśataṁ sopi sarvavyādhivivarjitaḥ॥— Sapta Chiranjivi Stotram

The mantra states that the remembrance of the eight immortals (Ashwatthama, Mahabali, Vyasa, Hanuman, Vibhishana, Kripa, Parashurama, and Markandeya) offers one freedom from ailments and longevity.

See also

- Hanuman temples

- Vayu Stuti

- Hanuman Chalisa

- Hanuman Jayanti

- Hanumanasana, an asana named after Hanuman

- The 6 Ultra Brothers vs. the Monster Army

- Hanuman and the Five Riders

- Gray langur, also known as the Hanuman langur

- Sun Wukong, a Chinese literary character in Wu Cheng'en's masterpiece Journey to the West

References

- ^ "Hanuman: A Symbol of Unity". The Statesman. 21 January 2021. Archived from the original on 31 January 2021. Retrieved 21 January 2021.

- ^ Brown, N.R. (2011). The Mythology of Supernatural: The Signs and Symbols Behind the Popular TV Show. Penguin Publishing Group. p. 44. ISBN 978-1-101-51752-9. Retrieved 4 January 2024.

- ^ Williams, G.M. (2008). Handbook of Hindu Mythology. Handbooks of world mythology. OUP USA. p. 148. ISBN 978-0-19-533261-2. Retrieved 4 January 2024.

- ^ Brian A. Hatcher (2015). Hinduism in the Modern World. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-135-04630-9.

- ^ "Hanuman" Archived 26 September 2020 at the Wayback Machine, Random House Webster's Unabridged Dictionary.

- ^ wisdomlib.org (16 January 2019). "Anjaneya, Āñjaneya, Amjaneya: 9 definitions". www.wisdomlib.org. Archived from the original on 13 November 2022. Retrieved 13 November 2022.

- ^ Bibek Debroy (2012). The Mahabharata: Volume 3. Penguin Books. pp. 184 with footnote 686. ISBN 978-0-14-310015-7.

- ^ a b J. Gordon Melton; Martin Baumann (2010). Religions of the World: A Comprehensive Encyclopedia of Beliefs and Practices, 2nd Edition. ABC-CLIO. pp. 1310–1311. ISBN 978-1-59884-204-3.

- ^ a b Paula Richman (2010), Review: Lutgendorf, Philip's Hanuman's Tale: The Messages of a Divine Monkey, The Journal of Asian Studies; Vol 69, Issue 4 (Nov 2010), page 32

- ^ Lutgendorf 2007, p. 44.

- ^ a b c d Jayant Lele (1981). Tradition and Modernity in Bhakti Movements. Brill Academic. pp. 114–116. ISBN 978-90-04-06370-9.

- ^ a b Lutgendorf 2007, p. 67.

- ^ a b c d e Constance Jones; James D. Ryan (2006). Encyclopedia of Hinduism. Infobase. pp. 177–178. ISBN 978-0-8160-7564-5. Archived from the original on 20 October 2022. Retrieved 26 May 2017.

- ^ a b c d Lutgendorf 2007, pp. 26–32, 116, 257–259, 388–391.

- ^ a b c d e f George M. Williams (2008). Handbook of Hindu Mythology. Oxford University Press. pp. 146–148. ISBN 978-0-19-533261-2.

- ^ a b Lutgendorf, Philip (1997). "Monkey in the Middle: The Status of Hanuman in Popular Hinduism". Religion. 27 (4): 311–332. doi:10.1006/reli.1997.0095.

- ^ a b Catherine Ludvik (1994). Hanumān in the Rāmāyaṇa of Vālmīki and the Rāmacaritamānasa of Tulasī Dāsa. Motilal Banarsidass. pp. 2–9. ISBN 978-81-208-1122-5.

- ^ Lutgendorf 2007, pp. 223, 309, 320.

- ^ Wendy Doniger, Hanuman: Hindu mythology Archived 15 April 2022 at the Wayback Machine, Encyclopaedia Britannica; For a summary of the Chinese text, see Xiyouji: Novel by Wu Cheng'En

- ^ H. S. Walker (1998), Indigenous or Foreign? A Look at the Origins of the Monkey Hero Sun Wukong, Sino-Platonic Papers, No. 81. September 1998, Editor: Victor H. Mair, University of Pennsylvania

- ^ a b c d e Lutgendorf 2007, pp. 31–32.

- ^ Gopal, Madan (1990). K.S. Gautam (ed.). India through the ages. Publication Division, Ministry of Information and Broadcasting, Government of India. p. 68.

- ^ a b c d Peter J. Claus; Sarah Diamond; Margaret Ann Mills (2003). South Asian Folklore: An Encyclopedia : Afghanistan, Bangladesh, India, Nepal, Pakistan, Sri Lanka. Taylor & Francis. pp. 280–281. ISBN 978-0-415-93919-5.

- ^ a b Lutgendorf 2007, pp. 50–53.

- ^ ऋग्वेद:_सूक्तं_१०.८६, Rigveda, Wikisource

- ^ Philip Lutgendorf (1999), Like Mother, Like Son, Sita and Hanuman Archived 29 September 2017 at the Wayback Machine, Manushi, No. 114, pages 23–25

- ^ Lutgendorf 2007, pp. 39–40.

- ^ Philip Lutgendorf (1999), Like Mother, Like Son, Sita and Hanuman Archived 29 September 2017 at the Wayback Machine, Manushi, No. 114, pp. 22–23

- ^ Nanditha Krishna (2010). Sacred Animals of India. Penguin Books India. pp. 178–. ISBN 978-0-14-306619-4.

- ^ Swami Parmeshwaranand (2001). Encyclopaedic Dictionary of Puranas, Vol. 1. Sarup & Sons. pp. 411–. ISBN 978-81-7625-226-3. Retrieved 14 July 2012.

- ^ a b c d Camille Bulcke; Dineśvara Prasāda (2010). Rāmakathā and Other Essays. Vani Prakashan. pp. 117–126. ISBN 978-93-5000-107-3. Retrieved 14 July 2012.

- ^ The Rigveda, with Dayananda Saraswati's Commentary, Volume 1. Sarvadeshik Arya Pratinidhi Sabha. 1974. p. 717.

The third meaning of Rudra is Vayu or air that causes pain to the wicked on the account of their evil actions...... Vayu or air is called Rudra as it makes a person weep causing pain as a result of bad deeds .

- ^ Devdutt Pattanaik (10 September 2018). Gender Fluidity in Hindu Mythology. Penguin Random House. p. 11. ISBN 9789353052720.

In Vaishnava traditions, Hanuman is not related to Shiva. In Shaiva traditions, Hanuman is either Shiva's avatar or son.

- ^ Shanti Lal Nagar (1999). Genesis and evolution of the Rāma kathā in Indian art, thought, literature, and culture: from the earliest period to the modern times. B.R. Pub. Co. ISBN 978-81-7646-082-8. Retrieved 14 July 2012.

- ^ Lutgendorf 2007, pp. 64–71.

- ^ Kane, P. V. (1966). "The Two Epics". Annals of the Bhandarkar Oriental Research Institute. 47 (1/4): 48. ISSN 0378-1143. JSTOR 41694199.

- ^ Catherine Ludvik (1987). F.S. Growse (ed.). The Rāmāyaṇa of Tulasīdāsa. Motilal Banarsidass. pp. 723–725. ISBN 978-81-208-0205-6.

- ^ a b Patrick Peebles (2015). Voices of South Asia: Essential Readings from Antiquity to the Present. Routledge. pp. 99–100. ISBN 978-1-317-45248-5.

- ^ Lutgendorf 2007, p. 85.

- ^ Lutgendorf 2007, pp. 57–64.

- ^ Thomas A. Green (2001). Martial Arts of the World: En Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO. pp. 467–468. ISBN 978-1-57607-150-2.

- ^ Philip Lutgendorf (2002), Evolving a monkey: Hanuman, poster art and postcolonial anxiety, Contributions to Indian Sociology, Vol. 36, Iss. 1–2, pp. 71–112

- ^ a b Encyclopaedic Dictionary of Puranas Vol 2. (D-H) pp=628–631, Swami Parmeshwaranand, Sarup & Sons, 2001, ISBN 978-81-7625-226-3

- ^ Lutgendorf 2007, p. 249.

- ^ Deshpande, Chaitanya (22 April 2016). "Hanuman devotees to visit Anjaneri today". The Times of India. Archived from the original on 13 September 2016. Retrieved 16 April 2021.

- ^ Bose, Mrityunjay (7 November 2020). "Maharashtra govt to develop Hanuman's birthplace Anjaneri". Deccan Herald. Archived from the original on 7 November 2020. Retrieved 16 April 2021.

- ^ Malagi, Shivakumar G. (20 December 2018). "At Hampi, fervour peaks at Hanuman's birthplace". Deccan Chronicle. Archived from the original on 31 May 2019. Retrieved 4 December 2020.

- ^ "Anjaneya Hill". Archived from the original on 31 May 2019. Retrieved 4 December 2020.

- ^ "Anjeyanadri Hill | Sightseeing Hampi". Karnataka.com. 22 October 2014. Archived from the original on 26 March 2023. Retrieved 4 December 2020.

- ^ Catherine Ludvik (1994). Hanumān in the Rāmāyaṇa of Vālmīki and the Rāmacaritamānasa of Tulasī Dāsa. Motilal Banarsidass. pp. 61–62. ISBN 978-81-208-1122-5.

- ^ a b c Lutgendorf 2007, pp. 188–189.

- ^ a b c d e Pai, Anant (1978). Valmiki's Ramayana. India: Amar Chitra Katha. pp. 1–96.

- ^ a b c d Pai, Anant (1971). Hanuman. India: Amar Chitra Katha. pp. 1–32.

- ^ Chandrakant, Kamala (1980). Bheema and Hanuman. India: Amar Chitra Katha. pp. 1–32.

- ^ Joginder Narula (1991). Hanuman, God and Epic Hero: The Origin and Growth of Hanuman in Indian Literary and Folk Tradition. Manohar Publications. pp. 19–21. ISBN 978-81-85054-84-1.

- ^ a b James G. Lochtefeld (2002). The Illustrated Encyclopedia of Hinduism: N-Z. The Rosen Publishing Group. pp. 271–272. ISBN 978-0-8239-2287-1.

- ^ Nityananda Misra. Mahaviri: Hanuman Chalisa Demystified. Bloomsbury Publishing, 2018.

- ^ Lutgendorf 2007, pp. 45–47, 287.

- ^ Goldman, Robert P. (Introduction, translation and annotation) (1996). The Ramayana of Valmiki: An Epic of Ancient India, Volume V: Sundarakanda. Princeton University Press, New Jersey. 0691066620. pp. 45–47.

- ^ Lutgendorf 2007, pp. 6, 44–45, 205–210.

- ^ Lutgendorf 2007, p. 61.

- ^ Lutgendorf 2007, pp. 140–141, 201.

- ^ a b c Catherine Ludvik (1994). Hanumān in the Rāmāyaṇa of Vālmīki and the Rāmacaritamānasa of Tulasī Dāsa. Motilal Banarsidass. pp. 12–14. ISBN 978-81-208-1122-5.

- ^ A Kapoor (1995). Gilbert Pollet (ed.). Indian Epic Values: Rāmāyaṇa and Its Impact. Peeters Publishers. pp. 181–186. ISBN 978-90-6831-701-5.

- ^ Roderick Hindery (1978). Comparative Ethics in Hindu and Buddhist Traditions. Motilal Banarsidass. pp. 100–107. ISBN 978-81-208-0866-9.

- ^ Wolcott, Leonard T. (1978). "Hanumān: The Power-Dispensing Monkey in North Indian Folk Religion". The Journal of Asian Studies. 37 (4): 653–661. doi:10.2307/2054368. ISSN 0021-9118. JSTOR 2054368. S2CID 162908060.

- ^ Lutgendorf, Philip (2001). "Five Heads and No Tale: Hanumān and the Popularization of Tantra". International Journal of Hindu Studies. 5 (3): 269–296. doi:10.1007/s11407-001-0003-3. ISSN 1022-4556. JSTOR 20106778.

- ^ Catherine Ludvik (1987). F.S. Growse (ed.). The Rāmāyaṇa of Tulasīdāsa. Motilal Banarsidass. pp. 723–728. ISBN 978-81-208-0205-6.

- ^ Catherine Ludvik (1994). Hanumān in the Rāmāyaṇa of Vālmīki and the Rāmacaritamānasa of Tulasī Dāsa. Motilal Banarsidass. pp. 1–16. ISBN 978-81-208-1122-5.

- ^ Peter J. Claus; Sarah Diamond; Margaret Ann Mills (2003). South Asian Folklore: An Encyclopedia. Taylor & Francis. pp. 509–511. ISBN 978-0-415-93919-5.

- ^ Dallapiccola, A.L.; Verghese, Anila (2002). "Narrative Reliefs of Bhima and Purushamriga at Vijayanagara". South Asian Studies. 18 (1): 73–76. doi:10.1080/02666030.2002.9628609. S2CID 191646631.

- ^ J. A. B. van Buitenen (1973). The Mahabharata, Vol. 2: Book 2: The Book of Assembly; Book 3: The Book of the Forest. University of Chicago Press. pp. 180, 371, 501–505. ISBN 978-0-226-84664-4.

- ^ Diana L. Eck (1991). Devotion divine: Bhakti traditions from the regions of India : studies in honour of Charlotte Vaudeville. Egbert Forsten. p. 63. ISBN 978-90-6980-045-5. Retrieved 14 July 2012.

- ^ Deussen, Paul (1997). Sixty Upanishads of the Veda. Motilal Banarsidass Publ. ISBN 978-81-208-1467-7.

- ^ Catherine Ludvík (1994). Hanumān in the Rāmāyaṇa of Vālmīki and the Rāmacaritamānasa of Tulasī Dāsa. Motilal Banarasidas publ. pp. 164–. ISBN 978-81-208-1122-5. Retrieved 14 July 2012.

- ^ Mystery of Hanuman Inspiring Tales from Art and Mythology –The Story of Ahiravan Vadh – Hanuman Saves Lord

- ^ Susan Whitfield; Ursula Sims-Williams (2004). The Silk Road: Trade, Travel, War and Faith. Serindia Publications. p. 212. ISBN 978-1-932476-13-2.

- ^ J. L. Brockington (1985). Righteous Rāma: The Evolution of an Epic. Oxford University Press. pp. 264–267, 283–284, 300–303, 312 with footnotes. ISBN 978-0-19-815463-1.

- ^ a b c Lutgendorf 2007, pp. 353–354.

- ^ a b Emiko Ohnuki-Tierney (1989). The Monkey as Mirror: Symbolic Transformations in Japanese History and Ritual. Princeton University Press. pp. 42–54. ISBN 978-0-691-02846-0.

- ^ John C. Holt (2005). The Buddhist Visnu: Religious Transformation, Politics, and Culture. Columbia University Press. pp. 138–140. ISBN 978-0-231-50814-8.

- ^ Hera S. Walker (1998). Indigenous Or Foreign?: A Look at the Origins of the Monkey Hero Sun Wukong, Sino-Platonic Papers, Issues 81–87. University of Pennsylvania. p. 45.

- ^ Arthur Cotterall (2012). The Pimlico Dictionary of Classical Mythologies. Random House. p. 45. ISBN 978-1-4481-2996-6.

- ^ Rosalind Lefeber (1994). The Ramayana of Valmiki: An Epic of Ancient India-Kiskindhakanda. Princeton University Press. pp. 29–31. ISBN 978-0-691-06661-5.

- ^ Richard Karl Payne (1998). Re-Visioning "Kamakura" Buddhism. University of Hawaii Press. pp. 65–66. ISBN 978-0-8248-2078-7.

- ^ Lutgendorf 2007, pp. 38–41.

- ^ Peter D. Hershock (2006). Buddhism in the Public Sphere: Reorienting Global Interdependence. Routledge. p. 18. ISBN 978-1-135-98674-2.

- ^ Reiko Ohnuma (2017). Unfortunate Destiny: Animals in the Indian Buddhist Imagination. Oxford University Press. pp. 80–81. ISBN 978-0-19-063755-2.

- ^ Louis E. Fenech (2013). The Sikh Zafar-namah of Guru Gobind Singh: A Discursive Blade in the Heart of the Mughal Empire. Oxford University Press. pp. 149–150 with note 28. ISBN 978-0-19-993145-3.

- ^ John Stratton Hawley; Gurinder Singh Mann (1993). Studying the Sikhs: Issues for North America. State University of New York Press. pp. 98–99. ISBN 978-0-7914-1426-2.

- ^ Devdutt Pattanaik (1 September 2000). The Goddess in India: The Five Faces of the Eternal Feminine. Inner Traditions * Bear & Company. p. 71. ISBN 978-0-89281-807-5. Retrieved 18 July 2012.

- ^ Lutgendorf, Philip (1997). "Monkey in the Middle: The Status of Hanuman in Popular Hinduism". Religion. 27 (4): 311. doi:10.1006/reli.1997.0095.

- ^ Philip Lutgendorf (2002), Evolving a monkey: Hanuman, poster art and postcolonial anxiety, Contributions to Indian Sociology, Vol 36, Issue 1–2, pages 71–110

- ^ Christophe Jaffrelot (2010). Religion, Caste, and Politics in India. Primus Books. p. 183 note 4. ISBN 978-93-80607-04-7. Archived from the original on 7 February 2023. Retrieved 28 May 2017.

- ^ William R. Pinch (1996). Peasants and Monks in British India. University of California Press. pp. 27–28, 64, 158–159. ISBN 978-0-520-91630-2.

- ^ Sarvepalli Gopal (1993). Anatomy of a Confrontation: Ayodhya and the Rise of Communal Politics in India. Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 41–46, 135–137. ISBN 978-1-85649-050-4.

- ^ Christophe Jaffrelot (2010). Religion, Caste, and Politics in India. Primus Books. pp. 332, 389–391. ISBN 978-93-80607-04-7. Archived from the original on 7 February 2023. Retrieved 28 May 2017.

- ^ Daromir Rudnyckyj; Filippo Osella (2017). Religion and the Morality of the Market. Cambridge University Press. pp. 75–82. ISBN 978-1-107-18605-7.

- ^ Pathik Pathak (2008). Future of Multicultural Britain: Confronting the Progressive Dilemma: Confronting the Progressive Dilemma. Edinburgh University Press. p. 18. ISBN 978-0-7486-3546-7.

- ^ Chetan Bhatt (2001). Hindu nationalism: origins, ideologies and modern myths. Berg. pp. 180–192. ISBN 978-1-85973-343-1.

- ^ Lutgendorf, Philip (2001). "Five heads and no tale: Hanumān and the popularization of Tantra". International Journal of Hindu Studies. 5 (3): 269–296. doi:10.1007/s11407-001-0003-3. S2CID 144825928.

- ^ Lutgendorf 2007, pp. 319, 380–388.

- ^ Lutgendorf 2007, pp. 59–61.

- ^ Hanuman Bearing the Mountaintop with Medicinal Herbs New York Metropolitan Museum. Ca. 1800. Retrieved April 6, 2024.

- ^ T. A. Gopinatha Rao (1993). Elements of Hindu iconography. Motilal Banarsidass. pp. 58, 190–194. ISBN 978-81-208-0878-2.

- ^ David N. Lorenzen (1995). Bhakti Religion in North India: Community Identity and Political Action. State University of New York Press. p. 271. ISBN 978-0-7914-2025-6.

- ^ Vanamali 2010, p. 14.

- ^ Lutgendorf 2007, p. 60.

- ^ Lutgendorf 2007, pp. 11–12, 101.

- ^ Reports of a Tour in Bundelkhand and Rewa in 1883–84, and of a Tour in Rewa, Bundelkhand, Malwa, and Gwalior, in 1884–85, Alexander Cunningham, 1885

- ^ Lutgendorf 2007, pp. 59–60.

- ^ "Hanuman Garhi". www.uptourism.gov.in. Archived from the original on 28 July 2020. Retrieved 28 July 2020.

- ^ "Five historical Hindu temples of Pakistan". WION. 17 February 2018. Archived from the original on 23 November 2019. Retrieved 4 December 2020.

- ^ Academy, Himalayan. "Hinduism Today Magazine". www.hinduismtoday.com. Archived from the original on 6 May 2019. Retrieved 4 December 2020.

- ^ The Indian Express, Chandigarh, Tuesday, 2 November 2010, p. 5.

- ^ Lutgendorf 2007.

- ^ Swati Mitra (2012). Temples of Madhya Pradesh. Eicher Goodearth and Government of Madhya Pradesh. p. 41. ISBN 978-93-80262-49-9.

- ^ Lutgendorf 2007, pp. 239, 24.

- ^ Raymond Brady Williams (2001). An introduction to Swaminarayan Hinduism. Cambridge University Press. p. 128. ISBN 978-0-521-65422-7. Retrieved 14 May 2009.

hanuman sarangpur.

Page 128 - ^ "Amit Shah Unveils 54-Feet-Tall Statue Of Lord Hanuman At Gujarat Temple". NDTV.com. Retrieved 10 August 2023.

- ^ New Hindu temple serves Frisco's growing Asian Indian population Archived 28 October 2017 at the Wayback Machine, Dallas Morning News, 6 August 2015

- ^ "90-ft Hanuman Statue of Union unveiled in Texas, 3rd tallest in US". The Times of India. 21 August 2024. ISSN 0971-8257. Retrieved 4 September 2024.

- ^ Schechner, Richard; Hess, Linda (1977). "The Ramlila of Ramnagar [India]". The Drama Review: TDR. 21 (3): 51–82. doi:10.2307/1145152. JSTOR 1145152.

- ^ Encyclopedia Britannica (2015). "Navratri – Hindu festival". Archived from the original on 22 February 2017. Retrieved 28 May 2017.

- ^ a b Ramlila, the traditional performance of the Ramayana Archived 31 January 2017 at the Wayback Machine, UNESCO

- ^ Ramlila Pop Culture India!: Media, Arts, and Lifestyle, by Asha Kasbekar. Published by ABC-CLIO, 2006. ISBN 1-85109-636-1. Page 42.

- ^ Toni Shapiro-Phim, Reamker Archived 29 November 2016 at the Wayback Machine, The Cambodian Version of Ramayana, Asia Society

- ^ Marrison, G. E (1989). "Reamker (Rāmakerti), the Cambodian Version of the Rāmāyaṇa. A Review Article". Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland. 121 (1): 122–129. doi:10.1017/S0035869X00167917. JSTOR 25212421. S2CID 161831703.

- ^ Jukka O. Miettinen (1992). Classical Dance and Theatre in South-East Asia. Oxford University Press. pp. 120–122. ISBN 978-0-19-588595-8.

- ^ Leakthina Chau-Pech Ollier; Tim Winter (2006). Expressions of Cambodia: The Politics of Tradition, Identity and Change. Routledge. pp. 140–141. ISBN 978-1-134-17196-5.

- ^ James R. Brandon; Martin Banham (1997). The Cambridge Guide to Asian Theatre. Cambridge University Press. pp. 236–237. ISBN 978-0-521-58822-5.

- ^ Margarete Merkle (2012). Bali: Magical Dances. epubli. pp. 42–43. ISBN 978-3-8442-3298-1.[permanent dead link]

- ^ J. Kats (1927), The Rāmāyana in Indonesia Archived 26 January 2021 at the Wayback Machine, Bulletin of the School of Oriental Studies, Cambridge University Press, Vol. 4, No. 3 (1927), pp. 579–585

- ^ Malini Saran (2005), The Ramayana in Indonesia: alternate tellings Archived 15 December 2018 at the Wayback Machine, India International Centre Quarterly, Vol. 31, No. 4 (SPRING 2005), pp. 66–82

- ^ Willem Frederik Stutterheim (1989). Rāma-legends and Rāma-reliefs in Indonesia. Abhinav Publications. pp. xvii, 5–16 (Indonesia), 17–21 (Malaysia), 34–37. ISBN 978-81-7017-251-2.

- ^ Marijke Klokke (2006). Archaeology: Indonesian Perspective : R.P. Soejono's Festschrift. Yayasan Obor Indonesia. pp. 391–399. ISBN 978-979-26-2499-1.

- ^ Andrea Acri; H.M. Creese; A. Griffiths (2010). From Lanka Eastwards: The Ramayana in the Literature and Visual Arts of Indonesia. BRILL Academic. pp. 197–203, 209–213. ISBN 978-90-04-25376-6.

- ^ Moertjipto (1991). The Ramayana Reliefs of Prambanan. Penerbit Kanisius. pp. 40–42. ISBN 978-979-413-720-8.

- ^ Hildred Geertz (2004). The Life of a Balinese Temple: Artistry, Imagination, and History in a Peasant Village. University of Hawaii Press. pp. 154–165. ISBN 978-0-8248-2533-1.

- ^ Pitoyo Amrih (2014), Hanoman, Akhir bisu sebuah perang besar, Pitoyo Ebook, archived from the original on 11 April 2023, retrieved 19 March 2023

- ^ Paula Richman (1991). Many Rāmāyaṇas: The Diversity of a Narrative Tradition in South Asia. University of California Press. pp. 38–39. ISBN 978-0-520-07589-4.

- ^ Amolwan Kiriwat (1997), KHON: MASKED DANCE DRAMA OF THE THAI EPIC RAMAKIEN Archived 4 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine, University of Maine, Advisor: Sandra Hardy, pages 3–4, 7

- ^ Planet, Lonely; Isalska, Anita; Bewer, Tim; Brash, Celeste; Bush, Austin; Eimer, David; Harper, Damian; Symington, Andy (2018). Lonely Planet Thailand. Lonely Planet. p. 112. ISBN 978-1-78701-926-3. Retrieved 1 February 2020.

- ^ Lutgendorf 2007, p. 211.

- ^ Tony Moore; Tim Mousel (2008). Muay Thai. New Holland. pp. 66–67. ISBN 978-1-84773-151-7.[permanent dead link]

- ^ "Wives Of Hanuman". Archived from the original on 3 January 2020. Retrieved 3 January 2020.

- ^ "Did you know how Dara Singh was chosen for the role of Hanuman in Ramayan?". mid-day. 30 May 2020. Archived from the original on 14 June 2020. Retrieved 14 June 2020.

- ^ "Hanuman: the journey of a mythical superhero". News18. 21 October 2005. Archived from the original on 14 June 2020. Retrieved 14 June 2020.

- ^ "5 Bollywood Movies About Hanuman". BookMyShow. 2 June 2017. Archived from the original on 29 March 2019. Retrieved 29 March 2019.

- ^ Bajrangi Bhaijaan (2015), archived from the original on 1 December 2017, retrieved 19 March 2019

- ^ "Revealed: Obama always carries Hanuman statuette in pocket". The Hindu. 16 January 2016. Archived from the original on 14 April 2021. Retrieved 8 April 2021.

- ^ Archived at Ghostarchive and the Wayback Machine: "Obama Reveals Lucky Charms During Interview". Associated Press. 16 January 2016. Retrieved 8 April 2021.

- ^ Amish Tripathi (12 March 2018). "What India can learn from 'Black Panther'". washingtonpost.com. Archived from the original on 19 May 2018. Retrieved 17 May 2018.

- ^ Nicole Drum (20 February 2018). "'Black Panther' Movie Had a Word Censored in India". comicbook.com. Archived from the original on 18 May 2018. Retrieved 17 May 2018.

- ^ "Rodrigo y Gabriela: Fusing Flamenco And Metal". NPR.org. Archived from the original on 28 August 2020. Retrieved 21 September 2020.

- ^ "White Monkey' Khon performance film to hit cinemas on December 5". NNT. 8 November 2022. Archived from the original on 5 December 2022. Retrieved 5 December 2022.

- ^ Samrat, Ujjwal (24 December 2022). "Who is AP in Ram Setu?". True Scoop News. Archived from the original on 16 January 2023. Retrieved 16 January 2023.

Bibliography

- Claus, Peter J.; Sarah Diamond; Margaret Ann Mills (2003). "Hanuman". South Asian folklore. Taylor & Francis. pp. 280–281. ISBN 978-0-415-93919-5.

- Lutgendorf, Philip (2007). Hanuman's Tale: The Messages of a Divine Monkey. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-530921-8. Retrieved 14 July 2012.

- Vanamali, V (2010). Hanuman: The Devotion and Power of the Monkey God. Simon and Schuster. ISBN 978-1-59477-914-5.

- Sri Ramakrishna Math (1985): Hanuman Chalisa. Chennai (India): Sri Ramakrishna Math. ISBN 81-7120-086-9.

- Mahabharata (1992). Gorakhpur (India): Gitapress.

- Anand Ramayan (1999). Bareily (India): Rashtriya Sanskriti Sansthan.

- Swami Satyananda Sarawati: Hanuman Puja. India: Devi Mandir. ISBN 1-887472-91-6.

- The Ramayana Smt. Kamala Subramaniam. Published by Bharatiya Vidya Bhavan (1995). ISBN 81-7276-406-5

- Hanuman – In Art, Culture, Thought and Literature by Shanti Lal Nagar (1995). ISBN 81-7076-075-5

Further reading

- Catherine Ludvik (1994). Hanumān in the Rāmāyaṇa of Vālmīki and the Rāmacaritamānasa of Tulasī Dāsa. Motilal Banarsidass. ISBN 978-81-208-1122-5.

- Helen M. Johnson (1931). Hanumat's birth and Varuṇa's subjection (Chapter III of the Jain Ramayana by Hemachandra). Baroda Oriental Institute.

- Lutgendorf, Philip (2007). Hanuman's Tale: The Messages of a Divine Monkey. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-530921-8.

- Robert Goldman; Sally Goldman (2006). The Rāmāyaṇa of Vālmīki: An Epic of Ancient India. Volume V: Sundarakāṇḍa. Motilal Banarsidass. ISBN 978-81-208-3166-7.

- Vanamali, Mataji Devi (2010). Hanuman: The Devotion and Power of the Monkey God Inner Traditions, USA. ISBN 1-59477-337-8.

External links

- Hanuman at Encyclopædia Britannica

![Five-faced or Panchamukhi Hanuman: Hanuman face, man-lion face, Garuda face, Boar face, Horse face. It is found in esoteric tantric traditions that weave Vaishvana and Shaiva ideas, and is relatively uncommon.[101][102]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/8/80/11TH_Rudra_Shiva_Hanuman.jpg/250px-11TH_Rudra_Shiva_Hanuman.jpg)